Philosophy and the Humanities The Best of www.ralphmag.org Volume Forty-One; [Issues 238 - 244] Mid-Summer 2014 |

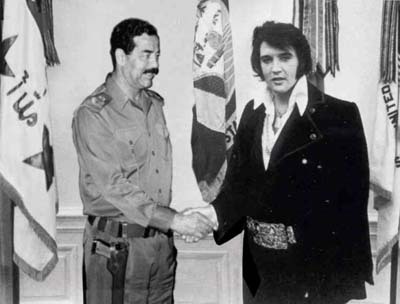

Saddam Hussein

- [On December 13, 2003, Iraq's former dictator was captured in Tikrit, hiding in a six-foot hole. At that time we issued a petition, asking that his life be spared for the future educative value of having him available to any and all historians, Muslim scholars, and psychologists. Our petition was denied, but we feel it should be useful as a guide for any American military who are still in the dictator arrest business.]

Hussein is an invaluable source of information for historians, students of Iraqi culture and politics, political scientists looking into the nature of power and tyranny, and, most of all, students of psychology. The chance for professors, graduates, and MA and PhD candidates to have their own personal despot on hand would be a crown jewel in the diadem of contemporary American scholarship.

Imagine the chance to study the very man who possessed and maintained absolute power in a neo-industrialized nation of some 20,000,000 people for almost a quarter-century. We can only begin to imagine the research that would flow from professors and students meeting face-to-face with this living tyrant, creating in the process worthy research into the social, psychological, historical, economic, physical and biological factors that created such an individual.

Although there are many people of Iraq and the United States who will demand the death penalty, this would be an appropriate time for the Bush administration to demonstrate --- at perhaps the deepest level --- what they have chosen to call "Compassionate Conservatism."

There are other factors that come into play. Ezra Pound once told a fellow writer that it would have been an act of mercy for the military authorities to have put him to death shortly after he was captured. He said that anything was preferable to being placed in a madhouse and subsequently being on call to any and all PhD and MA candidates and a variety of professors of various disciplines who were given unlimited access to study him in statu quo ante bellum.

Pound stated that being subjected to the questions of those who wished to build a career atop his poetic body was enough to drive a grown man mad. He considered the punishment as being even worse than being put to the rack, much less execution.

Once Hussein's trial is complete, it would thus behoove the current administration and the dictators' former supporters to see to it that he is thus protected from execution and placed in suitable quarters (Guantanamo Bay would be ideal) with the caveat that any and all students of Middle Eastern history, Iraqi culture, political science, government power strategy, third world economics, and psychology would have access to the prisoner any and all hours of the day or night.

"Would you call your mother a loving, responding individual?" might be an appropriate question addressed to the former tyrant. "Did you ever feel antagonism towards your father?" could be another. "Describe your early toilet training?" "When did you first masturbate?" "What did you think about when you were masturbating?" "Do you have any fetishes?" "Describe your earliest love affairs?" "Would you describe yourself as being a 'loving father'?" etc. etc. etc.

American scholarship, indeed, the very future of the present administration might well benefit from the in-depth study of one who had been there, done that.

It had been over a year since I experienced that level of pleasure and I was jonesing to feel so blank and cozy again. Only this time, unfortunately, there was no pain. I was sore, of course, but this was nothing like the twenty hours of contractions and the C-section I'd suffered through with Lucas. Eight hundred milligrams of Tylenol could have set me right. Nevertheless, I lobbied for the real drugs. The nurse administered it and I almost cried from disappointment.

Not only was I not enveloped in the warm embrace of a drug-induced high, the disappointment was dampening the natural high I was already experiencing from having my husband and ex-fiancé and ex-boyfriend all visiting at the same time. There I sat on a mechanical, Posturepedic dais, bald and one-titted, while the two exes rushed to fluff my pillows and Thibault studied my appearance, wondering if he had in fact won or lost. I should have been luxuriating in it, but instead I sat, frantically pumping the dosage button and worrying that my drainage bag would fall out of my gown and expose the bulb full of serum and lymph.

I stayed in the hospital for three days even though they said I could leave the day of the surgery. This was the first chance I'd had to be by myself since the diagnosis, and to sleep alone, no husband stealing the covers, no baby kicking me in the neck, since getting married. I felt like I was really on a vacation. I wasn't even encouraged to go out and play golf or swing on a trapeze. I could just stay in the room, read, watch television, and sleep. My nurses brought me food and changed my dressings and linens. My bed sat me up and laid me down. I had a nice, private room with a lovely view of the city. I didn't even have to be pleasant and chat up some roommate. It was blissful.

When I explained to the nurses that I didn't ever want to leave they looked at me like my labor-and-delivery nurse had when it was time to remove my catheter. I'd had it in for three days after my Cesarean and had grown to love it. It seems odd to adore a tube hanging from your crotch, attached to a plastic bag filled with warm urine, but I did. I'd spent the previous nine months running to the toilet every twenty minutes, day and night. The last two months I ran to the toilet and still peed on myself when I stood up afterward. It drove me crazy. Urinating effortlessly and at my leisure into a bag was down-right luxurious. I didn't even have to empty the reservoir. It was hidden under my sheets and I completely forgot about it until the nurses came to whisk it away...

Sunday morning, my last day in the hospital, Dr. Ree swung by to change my dressing. She had on yoga clothes and a backpack and looked about sixteen years old. She seemed very nervous and kept touching my shoulder. "Are you ready to do this?"

"Hell yeah!" I loved stitches ever since I was a kid and my father taught me how to take out my cat's. "Let's get a mirror!"

"Are you sure, Meredith? Sometimes people get upset."

"Whatever. There's a mirror in here." I led her into the little bathroom. She unswaddled my rib cage slowly. Finally, there it was. On the left side sat my smashed flat, deflated boob, and on the right side, nothing, just a thin line of steri-strip tape over the actual incision. Flat as a wall. There were no black stitches, no gruesome scar. It was just gone.

"You are a freaking magician! I so should have gone to medical school." I looked at it from every angle. Thibault had been lingering in the background but I pulled him in front of the mirror. "Look," I said. He looked perplexed, like it was some sort of smoke-and-mirrors trick.

We were both expecting a horror show, bear mauling, or something. But this was so tidy that it was hard to believe a breast had ever been there. Then she wrapped me back up and left. I was officially eligible to join the Amazon archery club.

Breast Cancer Can Be Really Distracting

Meredith Norton

©2008 Viking/Penguin

www.ralphmag.org/FF/breast-cancer.html

And the Changing Face of Motherhood

May Friedman

(University of Toronto Press)

-

I vividly remember feeling monitored when I was visibly pregnant. Feeling as though I'd get in trouble when I brought wine for cooking or beer for a party, or smelled or tried a sip of my partner's drink when we were out. And multiple baristas actually did try to correct me when I ordered various sorts of tea ("oh, that has caffeine; we have xyz herbal teas") ... let alone expresso. They gave up in the face of the Look of Death, as my mother calls it, but they still simultaneously pissed me off and made me feel small. (Even though the whole problem was that I was so big.) I've never as an adult felt so watched. so much under societal observance and --- potentially --- discipline.

Feminist Childbirth Studies

As quoted in Mommyblogs

Friedman began her blog readings online when she was pregnant, and found women in revolt against being thought of as in bliss at "the selfless natural state" ... when they were encountering nothing but "raw hard work."

When she started blogging ("like a beagle") she found that she was experiencing "a queering of motherhood," queer being used in the sense as propounded by Teresa de Laurentis in 1990, "the idea that identities are not fixed and do not determine who we are." What Friedman found herself involved in was unpacking "the category of mother."

Writers in the mamasphere floated innumerable odd concepts. For instance, that motherhood may not be "the perfect union of mother and infant to the benefit of both." Instead,

- most mothers recognize that the utter dependency of one of the actors in this dyad ... renders the duality of mother and child as parasitic rather than symbiotic.

Furthermore, because we are all taught to see the mother-child relationship as being "natural,"

- no further support from outside the mother-child dyad is proffered for the mother who might herself require caregiving.

The author quotes some blogs that boggle (or bloggle) the mind. A mother negotiating with the school system for an Individual Education Plan (IEP) tells us that she has to dress the part "to negotiate" for her son who is neurologically and physically disabled. "I wore a suit to these IEPs not because I had to, but because I wanted to send a message that I expected the best for Dear Son and that I would take nothing else."

A mother with an autistic child goes through genetic testing with her next pregnancy and reveals: "I am very pro choice --- but based on the papers I signed which allow them to keep my chromosomes and DNA on file at Columbia..."

- I felt the way the wind was blowing. Genetic Selection will become a reality. I just participated in the process. I did it for selfish reasons --- because I wanted to hear that my baby girl was ok.

Friedman's astute comments on this particular blog: "In the act of writing she challenges those who read it to similarly grapple with the ambivalent and contested spaces of motherhood, and in this grappling hybrid mothering emerges. This hybridity is especially obvious around tropes of the good mother."

And then there is this view of one mother concerning "all the poison cast towards Nadya Suleman" (who bore octuplets in 2009): "Got pregnant the old-fashioned way? She's a slut. Used a sperm donor and hired a nanny? She's a selfish old maid. Needs some public assistance? She's a leech on the taxpayer. Self-supporting? She's a workaholic."

- Can't anyone else see that the judgement hurled at Suleman is just a stone's throw from the judgement hurled at any single mother, regardless of how she came by her children.

I had never heard of "mamaspheres" before coming across this book. Might be because I am a workaholic, just didn't have the time to seek such things out. But Mommyblogs is a dream of good scholarship and wisdom. There is a neat encapsulation of the history of blogs and the radical change in what the author calls "the matricentric space." Her vision of blogs (and the internet) is rich.

She speaks of a "precariousness born of sheer abundance" in blogs out there. She discusses the fragility of it all: that one day a blogger may decide that she is going to drop the whole thing, and, unlike a book (which we own, keep on the shelf, can peruse anytime we want), her valued opinions --- and her equally valuable correspondence with readers --- will just disappear.

To create Mommyblogs, Friedman went through thousands of them, including the four most popular, Dooce, Finslippy, Fussy, and Her Bad Mother. Of the almost 200 places Friedman lists in the blogsphere, the names I liked the most were

- Gorillabuns

- Lesbian Dad

- A Frog in My Soup

- Baby Making Machine

- Attack of the Redneck Mommy

- Adorable Device of Destruction

- Cold Noodles for Breakfast

- Mrs. Fussypants

- Naked on Roller Skates

Jill Walker wrote that "the best way to understand blogging is to immerse yourself in it." Some readers of Mommyblogs may be put off by references to the likes of Mikhail Bakhtin ("cyborg storytelling" as "polyphony") or Michel Foucault (discourses on power) ... along with other elements of "postmodernism" which many of us are still grappling to understand.

Forget it. There are too many gems here that are worth your while. The new and, for me, very original concepts are sprinkled around like jewels, and they make reading the book worth your time and trouble. For instance, there is the idea that with birth one's "prior self" may become "irrelevant;" or the thought that a blog offers a different way of seeing "relational space;" or a simple idea, formulated in one blog that begins, "I have always been blatantly honest with you, blog people, even when my position is childish or selfish or silly. And so I am honest now:"

- Staying home with my kids is boring.

Of Horseshit

The other story comes from 1890s New York, when the city seemed in danger of drowning under a tide of horseshit. Rapid expansion, coupled with increasing dependence on actual horsepower to move goods, meant that there were too many animals in a restricted space. At predicted rates of growth the city would be buried in manure by the middle fo the 20th century. And then someone invented the motor car: the mess disappeared as if by magic. Now fracking stands to oil as oil once stood to horseshit. Salvation comes when you need it, if you have the nerve to wait. It's the American way.

The London Review of Books

21 March 2013

Jason C. Anthony

(Nebraska)

- Native Americans packed pemmican in bags of uncured bison skin sealed with fat. As bags dried and shrank, the food was as good as vacuum-sealed and could last for years.

Explorers and fur traders bought pemmican in large quantities as a key trade item, right up there with beaver, bear and deer hide. The food-stuff even managed to spout its own fracas (the Pemmican War) in 1816 Manitoba.

Hoosh is packed with facts about the cuisine of the Antarctic. Of all the delicacies there, the one at the top of everyone's Fantastic Food was seal brain. One of the explorer's chefs, Gerald Cutland, devised five recipes for this delicacy, including Seal Brain Omelette, Brain Fritters, and Seal Brains au Gratin. For an omelette, take "two seal brains, chopped up into very small pieces, four penguin eggs, some reconstituted eggs, butter, salt, pepper and mixed herbs."

Cutland might permit seal, but he put his foot down at making Penguin Pot Pie, or at least eating it. "When cooking Penguin, I have an awful feeling inside of me that I am cooking little men who are just a little too curious and stupid."

- A penguin even walked into his kitchen one day, and for a moment Cutland thought it was nice of the chap to come to the kettle so fresh, but he didn't have the heart to kill it: "Even though I have cooked many I have always left that job to those who would eat it."

A more typical menu was that enjoyed by the NBSAE expedition (1949 - 1952). "Seal liver and kidneys, breast of penguin with slices of bacon, braised whale steak with onions, whaleburgers, and grilled seal brains. Then there was the feast on local awful offal: heart, tongue, and liver of seal served up with heart, kidneys, liver and testicles of emperor penguin."

These are mostly menus from later explorations. The earlier ones were hardly gourmet journeys in any sense of the word, as the very expeditions themselves may have been nothing but self-promotion for people like Byrd and Scott. Writer Tom Griffiths suggests that "The heroic era of Antarctic exploration was "'heroic' because it was anachronistic before it began, its goal was as abstract as a pole, its central figures were romantic, manly and flawed, its drama was moral (for it mattered not only what was done but how it was done), and its ideal was national honour."

The biggies were Robert F. Scott's Discovery winters (1902 - 1904), Shackleton's South Pole journey, (1908 - 1909), Scott's disastrous Terrra Nova journey (1910 - 1912), Amundsen's successful polar trip (1911 - 1912), Shackleton's Endurance expedition (1914 - 1916), and Richard Byrd's ridiculous (and almost fatal) winter at the Barrier (1928 - 1930). One smaller expedition that Anthony digs up was Jean-Baptiste Charcot's 1903 - 1905 French Antarctic Expedition which "with little drama, settled in for a year to practice excellent science and boldly reveal new land" along the peninsula. The cook was named Rozo. He went about in slippers, baking bread three times a week, and using cormorant and penguin eggs for cakes and custards. No one knew where he came from, where he ultimately went: "another example," says the author, "of how the soul of the kitchen leaves only a faint trace in the mouth of history."

One foodstuff not emphasized was "eating the transport." Once ponies and dogs had outlived their use as pulling power, they became essential sources of protein. Old Dog Tray was fried or smoked, even cut up and carried along and eaten raw. En route, the many dogs were culled and killed and fed to the remaining dogs so they could keep on the job. Shackleton opined, "One point which struck us all was how man's attitudes towards food alters as he goes South. At the beginning, a man might have been something of an epicure, but we found that before he got very far even raw horse-meat tasted good." Amundsen put on the dog, too. He recalls the dishes "on which the cutlets were elegantly arranged side by side, with paper frills on the bones, and a neat pile of petit pois in the middle."

There are some fairly disgusting meals here which we need not spend much time on. One that sticks in the mind is Byrd's diet during his self-imposed two year stint at Little America. He never seemed to have mastered the art of melting butter in a frying pan (he cleaned it with a chisel). Lunch was eaten out of a can, dinners he called "a daily fiasco." The author tells us

- He ate mostly with his fingers, dining as a solitary man does --- and as Epicurus long ago noted --- like a wolf.

In Alone he claimed to have greeted his rescuers "Hello, fellows. Come on below. I have a bowl of hot soup waiting for you,"

Hoosh is about food but it is also about transport and logistics: how do you cook atop a mountain in -70° gale-force winds; how much energy should it take to transport so many calories across inhospitable terrain for so many miles so that it doesn't become counterproductive. You don't want to transport food that you will never consume. With these strictures, the law of eating your four-footed companions becomes somewhat more bearable.

Anthony pays due homage to the Primus stove, which contains an early feedback system so it can melt snow and heat hoosh. Melting snow takes lots of energy, too much. You think you are thirsty so you eat some snow, right? No. It will go to deplete your body's energy; it must be heated elsewhere. Energy, dehydration, caloric intake, scurvy, best foods to take on your next trip to Cape Well Met (citric, oatmeal, fat, pemmican, honey, dried fruit = yes; tinned beef, canned potatoes, Ben & Jerry's = no). A few recipes are included in the Appendix, including this for Sautéd Penguin:

- Penguin breasts

1 cup dried onion

1 tin tomatoes

1 tin tomato soup

4 ounces butter

Mixed herbs

Salt and pepper to taste

Cut the penguin breasts into small pieces and fry in the butter until brown then add the onion. Drain the tomatoes and mash half the tin into a purée, then stir into the meat and onion mixture. Add salt and pepper and some mixed herbs and the tomato soup. Simmer until the meat is tender and the sauce has been thickened.

This is fine adventure. The pretense is that it is the South Pole Lifestyle Cookbook but it is really an excellent summary of a time when to prove your manhood all you had to do was raise a million dollars and spend a year freezing your ass off in the most ghastly place on earth while starving.

We have previously posted a couple of on-line reviews and readings about roaming Antarctic Hot Spots. Most highly recommended is The Worst Journey in the World by Apsley Cherry-Garrard. And, although it is full of lies and general hooliganism, Byrd's Alone is worth it for the simple but poetic rendering of how to kill yourself in a romantic way.

That sun ray has raced to us

at those millions of miles an hour.

But when it reaches the floor of the room

it creeps slower than a philosopher,

it makes a bright puddle

that alters like an amoeba,

it climbs the door

as though it were afraid it would fall.In a few moments it'll make this page

an assaulting dazzle. I'll pull a curtain

sideways. I'll snip

a few yards off those millions of miles

and, tailor of the universe, sit quietly

stitching my few ragged days together.--- Norman MacCaigUpton Sinclair

California Socialist,

Celebrity Intellectual

Lauren Coodley

(University of Nebraska Press)Time magazine once reported that Sinclair Lewis "had every gift except humor and silence." This is doubtful since Lewis got his start as a writer of humor bits for student magazines. They were right about the silence business, though. Sinclair was incapable of it. In his ninety years, he wrote ninety novels. That's one-two-three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine ... with a little zero after it. Plus seventeen non-fiction works, six plays, and one anthology.Meanwhile, he sent himself through college, married three times, ran for the House of Representatives, then for the U. S. Senate, and, finally, governor of California (he got almost 900,000 votes). He spent his spare time speaking out in favor of contraception, socialism, labor unions, equality of the races --- and against bad food, whiskey, the oil industry, yellow journalism, the death penalty, and censorship. He even had a book banned in Boston because the phrase "birth control" appeared on one page --- although Sinclair was quite the prude.

He was friend to many of the radicals of his day, including Jane Addams of Hull House, Big Bill Haywood of the Industrial Workers of the World; Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Carlo Tresca, the anarchist; and John Reed, the future Communist. He also knew Walter Lippmann, John Dewey, Jack London, Charlie Chaplin, Walt Disney, George Bernard Shaw and, surprisingly, managed to be fast friends with Henry Ford and King Gillette --- of razor blade fortune. He met with Franklin D. Roosevelt at the president's home in Hyde Park, where improbably, according to Coodley, Roosevelt did all the talking and Sinclair did all the listening.

Sinclair had the ability to be unpretentious. A writer for Today magazine wrote of meeting with him. His house was described as "shabby."

Sinclair opened the door in his bathrobe. His face showed only faint lines of fatigue, and he answered one question after another sharply, concisely, and soothingly. His words rang with urgency but his voice was soft, his manner boyish, charming, bemused.

Evidently it was hard for people to dislike Sinclair, although he did get on a few nerves. When he published The Jungle they tried to get him together with Teddy Roosevelt, but TR told his publisher. "Tell Sinclair to go home and let me run the country for a while."

Still, it was impossible for Sinclair to carry a grudge, even against those who treated him badly. During the writer's campaign for governor, Ed Ainsworth, a reporter for the Los Angeles Times, was delegated to carefully cull quotes from Sinclair's books to convince the voters that he would turn the state Communist, with free love for all. Yet years later, while living in Monrovia, Sinclair and Ainsworth met. Ainsworth wrote,

My wife said to me, "Why can't you quit harboring grudges and go meet him and learn to like him? I've gotten to know him, and he's a sweet, kind, courtly old gentleman."

I suppose Sinclair could drive a soul mad. Kind, good, gentle, forgiving --- all those virtues that tend to make one crazy. He could be wrong, disastrously wrong: unlike Henry Ford, he supported World War One, sending out letters "that endorsed the war from a socialist perspective." In late life, he was all in favor of the Vietnam war, but that may have been because he had been invited twice to meet with President Johnson, and he died before the country was to rise up against further bloodshed.

§ § § Sinclair was able to pour out such a gusher of books because he learned when he was still in his twenties to dictate. He kept two secretaries busy for forty years, and didn't stop writing until a few years before he died. His great regret was that people mistook his causes. The Jungle was written from the perspective of the workers in the meat-packing plants, pointing out how they were getting screwed with lousy working conditions, terrible pay, all along, forbidden to unionize. That wasn't what people wanted to hear. One of the most appalling passages in The Jungle told of a worker who "fell into a lard vat and disappeared." Since most Americans didn't want to be eating their scrambled eggs mixed with meat-packer workers, the result was no change in labor's bargaining power or status, but rather, the Pure Food and Drug Act which only regulated the quality of our meat pies, not the insufferable working conditions.

Upton Sinclair is a mildly interesting book but Lauren Coodley has to deal with the intractable problem that is faced by all those who write about writers. Can she --- or any of us --- make this guy more interesting than he (or his writings) already were? Even a bare recitation of the facts (114 books; 879,000 votes; ninety years; three wives) exhausts the reader ... and the imagination. This guy was larger than life; and I suspect that a book doing full justice to him would, also, have to be larger than life.

--- Fran Winter

New Selected Poems

Les Murray

(Carcanet Press --- Alliance House

Manchester M2 7AQ UK)

Evidently Murray has been hanging out in the Australian outback for the last seventy-five years there with the Patagonian opossum, the pig-footed bandicoot, hairy-nosed wombats, and other marsupials:Shadowy kangaroos moved off

as we drove into the top paddock

coming home from a wedding

under a midnightish curd skythen his full face cleared:

Moon man, the first birth ever

who still massages his mother

and sends her light, for his havingbeen born fully grown.

His brilliance is in our blood.

Had earth fully healed from that labour

no small births could have happened.Usually, for us, when a poet catches us it's going to be some small image, a subtle cast, a way of lining up things we've never thought much of before.

Take hot-air balloons. All we know is what we've seen in the movies or in the funny-papers, but as the poet sees it, such a machine turns into a "basket-room / under the haunches of a hot-air balloon."

light-bulbs against the grizzled

mountain ridge and bare sky,

vertical yachts, with globe spinnakers.And then, the fall:

two, far up, lay overlapping,

corded and checked as the foresails of a ship

but tangled, and one collapsing.I suppress in my mind

the long rag unravelling, the mixed

high voice of its spinning fall.What Murray has done here is to take the very unexpected, precise image ... and made it into poetry (or horror) (or the two) ... for the rest of us. His writing is dream-like: he writes like a dream, with all those tag-end associations and hints always kicking around in our brains. When he speaks of glass-blowers, for example, those of us who have never been to a glass-blowing factory think little of it, but suddenly we come pure into it, for he paints it artfully: "the crush called cullet,"

which is fired up again, by a thousand degrees, to a mucilage

and brings these reddened spearmen bantering on stageEach fishes up a blob, smoke-sallow with a tinge of beer

which begins, at a breath, to distil from weighty to clear ...We've never been there, but it rings true, and so he has, by his art, put us there.

It can be something as profound as slavery, something as simple as pulling on a spiderweb,

crepe when cobbed, crap when rubbed,

stretchily adhere-and-there

and everyway, nap-snarled or sleek,

glibly hubbed with grots to tweek.What Murray is doing for us is the perfect show-and-tell, Empson's Seven Types of Ambiguity, with the added virtue of being able to turn a simple object of our lives into another. The common accordion becomes, "A backstrapped family Bible that consoles virtue and sin, / for it opens top and bottom, and harps both out and in ..."

It's no accident that Murray won our hearts so quickly. Turns out --- we checked with Wikipedia --- he has a special, spicy loathing for what the poetasters call "postmodernism." According to one critic, Murray has waged a "campaign for accessibility" in modern poetry. As we wrote recently on these very pages about a book of postmodern poems, "The editor says it is poetry. I say it's spinach, and I say to hell with it."

§ § § The irony is that Murray can out-postmodern the postmodernists, with their accent on the machinery of contemporary life. This is his riff on that moment when the airplane has "come to a complete stop" and we've stood up, pulling stuff out of the overheads, frozen in that breathless state before the doors open:

Soon we'll all be standing

encumbered and forbidding in the aisles

till the heads of those fartherest forward

start rocking side to side, leaving,

and that will spread back:

we'll all start swaying along as

people do on planks but not on streets,

our heads tick-tocking with times

that are wrong everywhere.What the poet has managed to merge here is a bag of associations: being weighed down (baggage, life); an ominous rocking or countdown with clocks; a dance maybe, along with pirates (and their planks!); and even (how did he do it?) slipping in a jet lag there at the very end.

We're trying to think of the last time we picked up a fat book of poetry by a single author and got as engrossed as we did with this one. There was, so many years ago, Howard Nemerov [www.ralphmag.org/CF/nemerov.html]: I read him through [we wrote] first to last; slept, woke up, read it back to first, marking the pages, wondering "Where has he been all my life?" We also think on the first time we looked into the works of Wislawa Szymborska, the first time we stumbled across Apollinaire (it was about time!), Quan Berry, and, praise the lord, New Direction's collection of Roberto Bolaño [www.ralphmag.org/FI/romantic-dogs.html].

Murray is hot. I leave you with one poem that shows him at his best. It's written in none but the simplest language, yet it manages to capture a whole era: understated, awful, precise, sad. It's called "Dog Fox Field."

The test for feeblemindedness was, they had to make up

a sentence using the words dog, fox and field.---Judgement at NurembergThese were no leaders, but they were first

into the dark on Dog Fox Field:Anna who rocked her head, and Paul

who grew big and yet giggled small,Irma who looked Chinese, and Hans

who knew his world as a fox knows a field.Hunted with needles, exposed, unfed,

this time in their thousands they bore sad cutsfor having gaped, and shuttled, and failed

to field the lore of prey and houndthey then had to thump and cry in the vans

that ran while stopped in Dog Fox Field.Our sentries, whose holocaust does not end,

they show us when we cross into Dog Fox Field.--- Sarah Maister, PhD

[LETTER OF THE MONTH]Bewear Sinner!I read your "Proof of Heaven." Bewear Sinner! The False Prophets (Nehemiah 8:13) are lose again. The socalled 'doctor' flies into the 'core' with angels and almost naked girl flyers. This is Statan's work and you give fame to false gods. You too will be cursed (Isa 22:15 - 17:) There is one god come to us in form of JESUS CHRIST the Only Begotten Son Lord Christ and Bewear! The devil is among you and they "acted presumptuously and stiffened their necks and did not obey your commandments" (Nehemiah 9:1-2) and there will be a violence on the land, the earth will shake and tremble, the sun and the moon shall a voice to rise from the deep:The mountains saw you, and writhed;

a torrent of water swept by;

the deep gave forth its voice.

The sun raised high its hands;

the moon stood still in its exalted place,

at the light of your arrows speeding by,

at the gleam of your flashing spear. (Habakkuk 3:10-11).Your come among us with the evil of false soothsayers that cause His Hand to reach down and smite you in the fire and in the pestelance:

and I will cut off sorceries from your hand,

and you shall have no more soothsayers; (Micah 5:12)Your like the sheep dealers and the neighborts will come to smite you and your land will be devasted and none to be deleivered from there hand:

For I will no longer have pity on the inhabitants of the earth, says the Lord. I will cause them, every one, to fall each into the hand of a neighbour, and each into the hand of the king; and they shall devastate the earth, and I will deliver no one from their hand. (Zechariah 11:6)

Your rebellion against Our Lord and Savior will cause retrubition the Hand of God Almighty to come from the clouds above you and smite you with a furie that will send you spinning in your death there on your very landhomdins:

Therefore thus says the Lord: I am going to send you off the face of the earth. Within this year you will be dead, because you have spoken rebellion against the Lord. Therefore thus says the Lord: I am going to send you off the face of the earth. Within this year you will be dead, because you have spoken rebellion against the Lord (Jeremiah 20:12)

Hark ye sinner!!!

--- Enid Washrow

MidolotheonTXThe review that inspired this letter

can be found at:

www.ralphmag.org/HV/proof-heaven.htmlThe Roy Stories

Barry Gifford

(Seven Stories Press)There are short stories and short-short stories. But this is the first time I have run across short-short-short stories, some 150 - 200 words, less than half-a-page. "Night Owl" is the winner, with a mere 136 words. Although, I have to admit it does work, and if I tried to tell you how I think it works, it would probably take a lot more than 136 words.Most of the stories involve Roy, as a kid, 10, 12 years old ... as old as 18. He lives in Chicago, New Orleans, Florida, and his father is an operator, and we're not talking telephones or doctors here. Rather, he's always stepping outside or inside or aside to talk "business" with his friends, driving to their place, leaving Roy in the car, or in a café somewhere, complete with five or ten dollars: telling him he'll be back soon. Sometimes he comes back later, sometimes he never gets back at all, once leaving Roy alone, waiting in the movie theatre. He often tells the boy that he'll come to school to watch his basketball game but he never seems to make it.

He's that kind of father: not bad, just never there. And after he dies Roy's mother begins to do the same thing. She takes up with other men, sometimes men who just appear out of nowhere. Most of them don't get along with Roy, and sometimes (between one just left, another not in place yet) Roy will work extra hard at the Red Hot Ranch where he works three days a week after school hoping to make enough money to keep Mom from taking up with yet another guy.

She will disappear and then reappear just as suddenly. "Through the front window he saw a white Cadillac pull up to the curb. His mother got out of the passenger side. She was dressed up to the nines, wearing a black cocktail dress beneath an ermine stole."

"Roy, darling," said his mother, "I'm glad I caught you."

She bent a little to kiss him but barely brushed her maroon mouth against his left cheek so as not to smear her lipstick.

Gifford is a master of the Dry American Direct school of writing, one that we've learned from other writers from the Middle West: Algren, Ellison, Richard Wright, Anderson, Hemingway. Gifford must also have studied The New Yorker in his youth, for his why-don't-we-just-stop-here endings made popular by the writers (and editors) of that magazine.

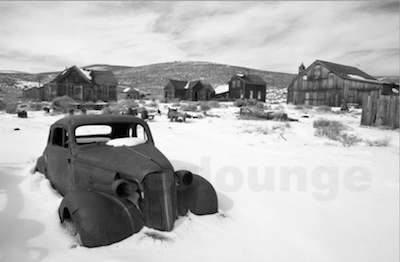

Although many of these stories are not what you would call gripping --- they're too truncated for that --- they do have a constancy, and a competence. You are there, in Chicago in the late 1950s, early 1960s, mostly winter: it is usually cold, snowy, icy, dark, wet, blowy. The streets are raw, and filled with characters with names like Double Trouble Korzienowski, Gin Bottle Sam, Demetrious Atlas (just in from New York) ... and a jokey friend of Roy's uncle's named "Chino:"

"Know why I'm called Chino?" he asked Roy.

"No, why?"

"'Cause my grandmother had a little yen."

Too, there's Large Jensen, Small Eddie Small, Lonely Johnny, Stuffy Foster (who drowned while doing basic training in South Carolina), Woody Crow (who "drove a tank over a cliff while on maneuvers in Düsseldorf and broke his neck") and The Pharaoh from Cairo, Ill.

The Pharaoh has one leg, regularly shoots pool at Lucky's El Paso poolhall, and could line up four balls "at one end of the felt, hit them one after the other only just hard enough off the rail so that they came back to exactly the same spot at which he'd placed them."

There are so many characters here --- each with his story to tell --- that you may feel like you've fallen into Damon Runyon territory ... only I found Gifford to be a bit more interesting. He's not just telling funny stories about funny eccentrics on Western Avenue, or weirdos down State Street, or odd-balls on Washtenaw, or Chick Ceccarelli who "fell to his death from a balcony on the tenth floor of an apartment building on Marine Drive" ("he was trying to walk on the top of the railing when he lost his balance.") Sometimes, though, the characters take over the story, drown us in details ... such as being told that "the apartment belonged to Loretta Vamp's mother's third husband Dominic Nequizia, who had been Jib Bufera's lawyer."

§ § § Not to carp. We have a link in it all, the necessary innocent anchor: Salinger's Glass family, Sherwood Anderson's George Willard, Bellow's Augie March. Here it's Roy, who comes across as your typical normal straight-arrow, a somewhat shy but often assured youngster of 1955, 1957 or 1962, living in Chicago with his mother, never really knowing his father, putting up with her continuous parade, most of whom drive him nuts (before they end up doing the same to her).

For instance, there's Sid "Spanky" Wade, a jazz drummer (he "spanks" the drums) who damn near drowns in the bathtub. "He had been smoking marijuana, fallen asleep and gone under. Roy's mother heard him splashing and coughing, went into the bathroom and tried to pull Spanky out of the tub, but he was too heavy for her to lift by herself." She calls Roy, and

Roy and his mother managed to drag Spanky over the side and onto the floor, where he lay puking and gagging. Roy saw the remains of the reefer floating in the tub. Spanky was short and stout. Lying there on the bathroom floor, to Roy he resembled a big red hog, the kind of animal Louie Pinna had shoved into an industrial sausage maker.

"Roy began to laugh. He tried to stop but he could not. His mother shouted at him. Roy looked at her. She kept shouting. Suddenly, he could no longer hear or see anything."

And that's how "Bad Things Wrong" ends, like so many of these --- they just up and end like that, as if Gifford had gotten lost or something, or just quit typing, no matter how interesting the story is getting to be. So then we find ourselves out of one and plop! into the next.

One never worries, though. These are like eating Fritos or Oreos or Doritos, or better, a great big wiener on the streets of Chicago, with just the right condiments. And it's impossible to stop. Stories like "The Vanished Gardens of Córdoba" just --- bang --- begin in the middle, then go away; and then we move on and it's O.K.

Some are jewels, though. Forget the title of "Close Encounters of the Right Kind" --- wrong decade --- which is about Fatima Bodanski, who had the reputation of being a "fast girl," and Roy falls in love with in an instant. Or try "Blue People" [below] about the Tuaregs and their dyed clothing. Or Roy visiting his old friend Eddie Derwood, committed to Illiniwek Psychiatric Institute. When he comes into the room, Eddie doesn't seem to see him. "His eyes were foggy and the corners of his mouth had white crust on them."

"It's me, Roy. Don't you recognize me?"

Eddie stared at Roy for thirty seconds before saying, "You're just a bird, a big, dark bird without wings."

Roy asks the attendant if he is on drugs. "'You don't know that' says the attendant. The attendant says to Eddie, 'You need somethin', Mr. Derwood. 'Caw! Caw!' said Eddie. 'Visit's over,' said the attendant."

The only time Roy could remember Eddie Derwood losing his temper was once when they were fifteen at Eddie's house and his mother told Eddie that he was not as smart as his older brother, Burton. Eddie sprang from his chair like a leopard catapulting out of a tree onto an unsuspecting passing animal and grabbed his mother with both hands around her throat pinning her against a wall.

"Eddie held her there for several seconds before letting go. He did not say a word and neither did his mother. Eddie sat down and his mother left the room. Roy did not go back to Eddie's house again for a long time after that."

--- Monica Myles, M. A.Blue PeopleRoy's fascination with maps began before he was eight years old. His curiosity about what people in distant lands looked like, what languages they spoke, and their customs, accelerated the more he read about countries whose names and geography he discovered in the Great World Atlas.In school one day, a substitute teacher named Arvid Scranton mentioned that just after the war he had been stationed in North Africa, and had traveled extensively in that region. In Morocco, he told Roy's class, he had been in a place called Goulimime, at the edge of the Sahara desert, where he had encountered the Blue People, a nomadic tribe called the Tuareg, who wore blue robes dyed with natural indigo that was absorbed by their skin and turned it blue. Many people believed, said Arvid Scranton, that the dye had become so pervasive over time that it entered the Tuaregs' bloodstream to the degree that their babies were born with a decidedly blue tinge to their otherwise black skin.

Roy was eleven when he learned of the existence of the Tuareg. A year later, he was playing in a basketball tournament at Our Fathers Out of Egypt, when he saw a blue person. The center on the team from Kings of Assyria had skin that was exactly as Arvid Scranton had described: deep, dark blue that glowed under and despite the dull yellow gymnasium lights. The kid on Kings of Assyria was taller than anyone else on either team and extremely thin, so thin that he was easily pushed around and brutalized by shorter but stockier opponents. Occasionally, he lofted a shot high over a defender's head that was impossible to block, but more often than not it clanged harmlessly off the rim of the basket, or banged too hard against the backboard. The kid had no touch, as well as not enough strength, and his team was easily defeated. After the game, Roy was tempted to ask him if he was related to the Tuareg of the Sahara, but he was afraid the kid would be offended, so he did not.

Later at Meschina's Restaurant, Roy and Jimmy Boyle were sitting at the counter eating club sandwiches and drinking Dad's root beers, when Roy told Jimmy about the Blue People, and how he figured the kid on Kings of Assyria must be related to them.

"You ever seen anyone else with skin dark blue like that?" Roy said.

Jimmy's mouth was too full to speak, so he just shook his head.

Lorraine, a waitress who had worked at Meschina's for forever, stopped in front of the boys and said, "My skin is black upon me, and my bones are burned with heat."

"'What's that?" asked Jimmy. "You aint black, and it's freezin' outside."

"Job, 30:30," said Lorraine. "I heard you talkin'. Kid must be descended from those desert people, the ones move around all the time."

"Nomads," said Roy.

"Roy says they turn blue because of the dye on their robes," said Jimmy.

"Very clever," Lorraine said. "I wish I could just wear a red babushka over my hair to make it stay red, then I wouldn't have to pay the beauty parlor no more."

As Roy and Jimmy walked home from Meschina's, the sky got dark fast and snow began to fall. A hard wind made them duck their heads.

"The weather in Chicago'll turn you blue, too," said Jimmy, "You get stuck out in it too long."

"Good thing that blue kid couldn't shoot," Roy said.

"He could," said Jimmy, "nobody'd stop him."

"He's too skinny," said Roy, "but if he keeps playin', he'll learn how to score and beef up as he ges older. Probably be a pro, he grows more."

"Good thing for him his family moved here," said Jimmy. "I bet they don't play basketball much in the Sahara desert."

--- From The Roy Stories

Barry Gifford

©2013, Seven Stories Press

Fine Bonsai

Art & Nature

William N. Valavanis

Jonathan M. Singer, Photographer

(Abbeville Press Publishers)A bonsai doesn't exactly look like that fir tree in your backyard shrunk down to size, nor the loblolly next door turned into a dwarf, or the black oak down the street in miniature. No --- a bonsai looks more like a torrey pine along the Pacific shoreline that's been blasted by the winds of March for the last seventy years, bent-over, doubled back on itself, bark torn away and worn, limbs twisted every whichaway ... but only 30 inches tall.You take this clipping from a perfectly normal black pine --- say --- and stick it in a bitty pot, with a handful of dirt and stone and porous rock, and set it off in the corner of the garden or near a window in your house. You come and look at it every day (one of my friends even talks to hers, like that old song, remember, "I talk to the trees / But they don't listen to me.")

You care for it, spritz it some, trim it on occasion. Be sure it gets sun, and when it has reached a certain size, you take the clips to it, pin on a wire or a stick or both ... set it so the tree will grow the way you want it to grow, not how it wants to grow. A little arbolistic tyranny, no?

I must confess I have some reservations about this business of taking a plant or a seed and watching it grow and then you "train" it like a soldier or a dog. But there is something going on here ... and it is supremely well represented here. The tiny trees have come into their own in this huge tome, a book that weighs in at 10 pounds, size 12" by 15", crammed with 300 full-size shots.

Fine Bonsai is not only a work of art, its a work of passionate intensity and love, and it is so huge --- in construction and passion --- that you can't help being smitten. I had to lay it out on its own table, and spend a few hours poring over it. After a while, I was a goner.

§ § § How long does it take to create Bonsai? Anywhere from five, ten, or twenty years ... to a millennium. Honest. The oldest one we found in this collection is a Sargent Juniper named "Kami No Yashiro" (they name these babies, like dogs or racehorses) located in Saitama City, Japan. For being so old and hoary it's not all that big: a little over two-and-a-half feet tall. The trunk is swirly, like a swirl of a storm wave. Age: estimated at 800 years. That means that "Kami No Yashiro" was just a bit of a seed before Dante conceived his bottom-up view of the world, long before the Tale of Genji ... perhaps coming to fruition at the same time that Beowulf was being written out by the monks in their cloister. Even before Chaucer started his pilgrims on their journey to Canterbury, "Kami No Yashiro" was starting on his journey.

Humans have spent whole lives constructing these living works of art, weaving subtlety and texture directly into nature. Consider a Juniper named "Seifu." It's twenty-six inches tall, most of the trunk desiccated, bone white, beautiful in twist with a slim reddish-brown section that provides water and nutrient to the upper part of the plant. It lives in Tokyo, in the Shunka-en Bonsai Museum, and since I have a yen, if I could rustle up the yen I would like to visit Seifu at home, look at him (or her) for a couple of hours. Under the tiny cap of greenery, this bark, this trunk, this wave of wood with its various outcroppings that remind me of a storm, a lightning flash; or maybe we can see it as representing the very bend and twist of our own lives, you and I as we age, the turns and twists of our bodies, a living essence that --- in Seifu --- was coming into being as Beethoven was writing his Ninth, Schubert penning "Death and the Maiden," Keats dying of the White Plague there on the Spanish Steps of Rome.

Some of these plants are downright weird. There's a Bald Cypress that is, truly, not only bald, it's damn near naked, looks like the aftermath of an attack from Agent Orange. Turns out it's deciduous, so we may have to visit him some other time to see him at his best. He lives in Federal Way, Washington. Have you ever been to Federal Way? It's like Rahway or Altoona or Fresno or Dallas on a bad day. But evidently, from those on displayed here, Federal Way is a hotbed of bonsai collectors, home to the Pacific Rim Bonsai Collection. There are nine such bonsai gardens listed in Fine Bonsai where you can go just to look at these miniatures.

The monster bonsai of them all is a Trident Maple who also resides in Federal Way. This one is seven feet tall, but he has a good excuse. His owner, Toichi Domoto, was shipped off to an internment camp by those nitwits in the 1940s version of Homeland Security, during WWII. Domoto couldn't tend it for four years, but maples can be tough: it grew right through the box, took root in the ground, and thus survived to appear here, lovely and leafy and somewhat lachrymose (being separated from your owner can do that to you if you are a good bonsai) to finally appear in this book.

Second tallest is a Blue Atlas Cedar, but she cheats: she has been encouraged to grow sideways and downwards, reaching out of her tiny container some five-and-a-half feet towards the ground. According to the author, Blue Atlas got to where she is by continual "pinching" --- not pinching like you would try on a geisha, but on the foliage to make it mass downwards. And actually no one in their right mind would pinch a geisha, and I'm not so sure I would ever pinch a bonsai, especially one this old (she's seventy if she's a day).

For smallest bonsai, it's a tie between an English Ivy at the Huntington Museum or a Star Jasmine at the Omiya Jasmine Village, Japan. Both of them come in at just over fifteen inches. The gaudiest (in my opinion) is the Kirishima Azalea, drenched in gorgeous tiny blossoms. The homeliest? It looks like a green triangle, and it is a Trident Maple. This poor baby had to put up with endless pinchings to build "a dense crown of small foliage." It occurs to me that these people torture their plants to make them stay with the program.

Take the lovely Japanese Spindle in Rochester N.Y. whose dainty red fruits are not even permitted to be eaten but are left there on the tree. "In early autumn the fruits become plump and slowly open, revealing a bright orange seed in the center of each." The author tells us the original cutting was purchased in Seattle. "and has been completely container grown and trained." Potty trained, too? Yes. It is potted in a lovely dark blue, nearly black-glazed Chinese container "to provide extra contrast with the fruit." Who is to free this tormented orphan bonsai?

§ § § So here we have a scandal finally revealed in this elegant volume. Instead of being titled Fine Bonsai, it might well have been named Abusing Your Cedar. An artist by the name of Shen Shaomin has documented the brutalities inflicted on these inoffensive plants. Shaomin's on-line illustrations show the machinery by which these plants are forced into bizarre positions, shapes and configurations. "Wire cable, clamps, metal plates are used to 'torture' each bonsai tree into strange positions," he writes. His images at

http://www.designboom.com/art/shen-shaomin-bonsai-series/

are shocking: he shows twenty-two tiny instruments of torture (pliers, twisters, cages, splints, scrapers and points) that are used on a benign hinoki cypress, an innocent black pine, a gentle border privet, a shy juniper. Then there is an oriental photinia, an unassuming red-leaf hornbeam, a bashful trident maple, a frail japanese beautyberry, a quiet firethorn, a hoary hornbeam, a lonely Japanese snowbell cedar or black pine shown forced into confinement in a teeny pot with scarcely room for its crowded little roots ... constantly being jabbed and punched and trimmed and twisted, perhaps even being scolded when it tries to escape its little prisons.

The American Nurserymen's Association should take action at once, report the widespread abuse aimed at these innocent plants who have, we are certain, done no wrong. We suggest, no, we demand that The Ladies Garden Clubs of America, The Men's Garden Clubs of America, The National Association of Flower Arrangement Societies, The Future Farmers of America and all 4-H Clubs unite to take arms, rise up in force, move into action --- issue a trumpet call to save our trees from what we now know to be Bonsai Bondage.

We plant lovers should unite, too, to praise Abbeville Press for issuing this manifesto --- a ten pound "J'accuse," a call to arms --- citing these who are, as we speak, inventing new tortures for these innocent plantlings, whose only crime is that they tried to Grow Free ... but are now subject to treely bondage, forbidden the height they deserve, kept down by these arboltrary masochists.

All they are asking --- and all we should ask for them --- is that they be permitted to stand tall once again, with dignity and justice for all.

--- Pamela Wylie§ § § [LETTER]Mr CarlosWith my newfound unimaginable interest in this article and Pamela Wylie I would ask of you to forward this email to her and tell me: is this article as a whole approving Bonsai and making mock of the mentioned artist or is it genuine in its final opinion that Bonsai is cruel and should be stopped in its practice?

I am undecided

Looking forward to hearing from either or both you and Pamela

Good day to you,

F Viljoen§ § §

Dear F. Viljoen:Thank you for your letter of inquiry about organizations established to prevent people from torturing normal happy trees --- merely to turn them into expensive bonsai --- as outlined in Pamela Wylie's review of the Abbeville Press edition of Fine Bonsai: Art & Nature.

We questioned her closely about these allegations to verify her "call to arms --- citing these who are, as we speak, inventing new tortures for these innocent plantlings, whose only crime is that they tried to Grow Free ... but are now subject to treely bondage, forbidden the height they deserve, kept down by these arboltrary masochists."

Her response, and I quote directly: "I would never knowingly fabricate a fact merely to doll up one of my reviews for you. If you think I could be so crass, perhaps I should take my reviewing talents some place else. It's your call."

Not daring to antagonize a talented and long-serving writer such as Ms. Wylie, we immediately apologized, said that --- as far as we were concerned --- we would back her to the hilt, no matter how quaint her premises.

She seemed satisfied, and assured us she would continue sailing with us on the Good Ship RALPH.

--- Ed.

Wm & H'ry

Literature, Love, and the Letters

Between William and Henry James

J. C. Hallman

(University of Iowa Press)You might have to be a Modern Language Association freak to get into this one.Like death and old age, 19th Century philosophers and novelists are not for the fainthearted. They worked at a slow burn, were not about to hurry their pace to fit the needs of a reader, especially a modern-day reader. Think Søren Kierkegaard, Friedrich Nietzsche, Emmanuel Kant. Or if you are of the novelistic persuasion, try Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Charles Dickens, William Makepeace Thackeray. See if you can stuff them into a single evening by the crackling fireside, or, perchance, a weekend at the windswept lakeside cottage.

Wm & H'ry (a take on the way each of them signed their letters) is obviously a work of extreme devotion. Although William and Henry might be considered by many of us to be a bit windy, this essay --- really, a love letter to them from Hallman --- is short and pithy, weighing in at a scant 122 pages, with fifteen pages of notes, by my inexact calculations, a ratio of one page of notes to 8.13333 pages of text.

Hallman tells us that he went to extraordinary lengths to access the letters between the two, which was the fault of his coming across something that you and I might be more inclined to use as a gadget to prop up a wobbly desk, or righten the lopsided dining room table, or stop the door. It consisted of twelve bound volumes of The Correspondence of William James: William and Henry published by the University Press of Virginia.

That's what got to Hallman --- everyone has their vice --- and, to complicate matters, he got stuck on volume twelve. The local library wasn't about to loan out their sole copy, certainly not to some struggling English Lit major who walked his dog and did his homework at the "outdoor tables of a Vietnamese restaurant for cheap lunches."

Not having access to the last volume would compromise Hallman's efforts, made even more onerous by the chance to buy the entire set (emphasis his) "for $315, which was then about half my net worth." I read this and I am thinking that with this kind of literary love, who are you or I to fault the subjects. William and Henry may be, to the nth degree, stuffy, but to Hallman, they were literary, philosophical, and philological giants. Their letters pleased and challenged him. Most especially the key question that got him: How much did they influence each other?

I am the last to rob you of your pleasure with this slim volume, but I am here to tell you that Wm & H'ry can be fun, even if you are put off (a bit, not too much I hope: it's love after all) by the author's assertion that "Henry James is the most pivotal author of the last 150 years" (hear that Joyce? Faulkner? Proust? Nabokov?) And that "William James is the father of modern psychology" (ditto Freud? Jung? Charcot?)

But ignore the hyperbole. You won't get any clues about Henry's sex life (who cares, anyway?) but you will find out more than you want to know about Henry's digestive system ("Never resist a motion to stool" was is his brother's advice ... and he ain't talking bar-stool, either).

You will also discover a couple of wonderful drawings [See Fig. 1 above] by William, showing Henry's forth-coming sleeping arrangements in Cambridge when he came to visit. Yes, they slept together, in the same bed, but it was the custom of the times (Abraham Lincoln did it for years) and, in the case of Wm & H'ry, was only, we assume, in the name of brotherly love.

In these letters you will also find a fascination with the word "whirligig;" you'll even run into a word you may never have heard before: "fizzling." It was in William's reaction to James' The Wings of the Dove: "I went fizzling about concerning it." (He was, mostly, puzzled by his brother's novels.)

There is some back-and-forth about the myth of the long-suffering artist, viz. "All intellectual work is the same --- the artists feeds the public on his own bleeding insides." William also suggests why many of us don't commit suicide when we get the blues. In responding to a document titled, "Is Life Worth Living?" he

cited two good reasons for sick souls distracted by thoughts of the abyss to plod along for at least another twenty-four hours: the daily newspaper, and "to see ... what the next postman will bring."

This is perhaps more satisfying than Hallman's rephrasing the philosopher's defense of pragmatism where the biographer is beginning to copy-cat the writing styles of at least one of his subjects: "we each have the right to supplement observable reality with an unseen spiritual order if only to thereby make life seem worth living."

There are some ravishing passages here, and not all of them from the brothers. William is concerned with the "chamber of the brain," the "true hope of breaching the membrane that kept us separate and discrete." In this, (William, Henry, and J. C. --- and from now on, me) are quoting Robert Louis Stevenson:

No man lives in the external truth, among salts and acids, but in the warm phantasmagoric chamber of his brain, with the painted windows and the storied walls.

That single line might be worth the price of admission to Wm&H'ry.

Like the Buddhists, William was concerned with the "blooming, buzzing confusion" of the mind. He first called it the "procession through the mind of groups of images." Then:

Our minds are all of them like vessels full of water, and taking in a new drop makes another fall out.

And with this, we are allowed to see the earliest incarnation of the now all-too-famous phrase "stream of consciousness,"

Consciousness, then, does not appear to itself chopped up in bits. Such words as "chain" or "train" do not describe fully as it presents itself in the first instance. It is nothing jointed; it flows. A "river" or a "stream" are the metaphors by which it is most naturally described. In talking of it hereafter, let us call it the stream of thought, of consciousness, or of subjective life.

Just think, it could have been the river of consciousness. Or the train of subjective life. Or the far more prosaic stream of thought.

§ § § You will miss something in this review. It has to do with the print trade, and HTML, and the like. I have yet to find in the codes coming out of the computer cloud, the likes of one charming bit that Hallman throws in throughout the book. It's 19th Century abbreviation for "William," a "W" with a tiny, underlined, uplifted "m" just to the right.

That was the way William signed his name.

It's easier with Henry which becomes, in the text here, H'ry. Both give a Victorian touch. With eight mail-calls a day, we wrote many letters, signed our names hastily.

Let's offer the last word to poor, gut-pained, stool-straining William. Those who favor his novels will know that it is often his ravishing descriptions that highlight the drama against which he plays his characters. This is his vista from Transatlantic Sketches of Lake Albano, in Italy:

This beautiful pool --- it is hardly more --- occupies the crater of a prehistoric volcano --- a perfect cup, moulded and smelted by furnace-fires. The rim of the cup rises high and densely wooded around the placid, stone-blue water, with a sort of natural artificiality. The sweep and contour of the long circle are admirable; never was a lake so charmingly lodged. It is said to be of extraordinary depth; and though stone-blue water seems at first a very innocent substitute for boiling lava, it has a sinister look which betrays its dangerous antecedents. The winds never reach it, and its surface is never ruffled; but its deep-bosomed placidity seems to cover guilty secrets, and you fancy it in communication with the capricious and treacherous forces of nature. Its very color has a kind of joyless beauty --- a blue as cold and opaque as a solidified sheet of lava. Streaked and wrinkled by a mysterious motion of its own, it seemed the very type of a legendary pool, and I could easily have believed that I had only to sit long enough into the evening to see the ghosts of classic nymphs and naiads cleave its sullen flood and beckon to me with irresistible arms.

--- L. W. MilamThis elegant boxed set consists of what we believe to be the best of the best drawn from the on-line magazine and its immediate predecessor, the late-lamented Fessenden Review. These are articles, reviews, readings and poems that have consistently garnered the most praise, attracted the most hits --- or, in a few cases, sparked the most noisome complaints.

Iowa & Other AccidentsThere was snow that afternoon covering the road

which twisted toward the secret

of water, the mysterious surgeof sludge & loam, the living

Mississippi, unlike the rest of the Midwest,drawing itself through landscape. There was an appointment

you were keepingin Moline: a cheap hotel, booze, a little blow. On the Lower

East Side, a womanspills her martini, makes a gesture

like erasure, or regret. It was almost Christmas.

In the rear viewsuddenly, the car you will always describe as oncoming

must have slipped into a skidand now, rising up over the bank,

it startles you --- that reflection. In Molinethe maid corners the bed, straightens the clean

line of sheet. Almost Christmas. On the road,

swirls of snow. On the roadthe car hovering behind you, a witness,

unfortunate & so unlike the audience permitted

the distance of fictions, the artificeof plot. And worse, of course, the law

of cause & effect: I looked up,

it started to fall. You must attachsubject to verb, must say

I saw, and did, in your rear view, the car you'd thought

nothing of,the gray sedan lifting slowly from the common snow,

turning, and the accident

always there, about to happen.

--- ©2011 Kate Northrop

Clean: Poems

The Old Priest

Stories

Anthony Wallace

(University of Pittsburgh)You remember the old priest: you knew him back when you were at the Catholic boys school and you keep up with him long after you went off and tried to become a writer and gave up and became a blackjack dealer instead but you always came back to visit because he was dry and astute, a charming old wit --- his cigarette holder, drinking good wine and remembering his good times in Europe, where he was to go to the Sorbonne but the Jesuits had other plans for him.Now that he's getting older he repeats himself but you got in the habit for so many years of visiting him with your newest latest girlfriends that you keep on doing so, introducing him to the shy one, or the gold digger, or Mildred who after she meets him, whispers that "all Catholic school boys are gay."

The old priest is a philosopher, a man who will explain to her the difference between "ecstasy" (the noun) and ekstasis. He says that this last means to "stand outside oneself," to "escape from the prison of the body."

Isn't that what everybody wants, after all?

he asks her. "I guess I've never thought about it that way," she says.

The second person singular narrator here is a bit of a philosopher too. He tells us that "there are those who stand inside history and those who stand outside, like beggars at the gate." It's "like penetrating time," he suggests. He reveals to us, the readers, that he is writing a book "of eternal and meaningful recurrence," and it is going to be called The Old Priest.

So here we are in the midst of this old writer's trick, that of writing a story about writing a story while, at the same moment, you're in the story. The novel is published, and it is a short one for people who would like to say that "they've read a novel but don't want to spend much time actually doing it."

The author reports that books about priests are hot now because of the sex scandals in all the newspapers. The editor of The Old Priest likes the book because the writer's subject, the old man, is not necessarily evil nor good, but rather, represents "the fine line down the middle." Only we don't know if this is so because as we arrive to the final pages, we find out that, indeed, the writer, as a young man, stayed up all one night with the priest, was seduced, presumably, and later recalls, fondly, when they went swimming in the ocean where the old man sang "O Mio Babbino Caro," and plunged "up and down in the easy current."

You can still see his face as it was in the early sunlight, spouting water from both nostrils and singing in Italian. Later you cooked cheese omelets then lay together side by side on the pullout sofa that was his bed, holding hands.

§ § § I often wonder about people who edit collections of short stories, wonder what they think when they put them together. Do they think, "I'd better put this one at the beginning because that's what most people will do, start out with the first story, and this one is hot." And it is.

And then they think: maybe we should put the second best at the end because some people (e.g., your reviewer) start anthologies from the back, work their way forward. (I also do this with "The New Yorker" because it's too much work to start at the beginning with its fat calendar and then What's Going on About Town ... a "town" where I don't live, never have, and never will.)

The editor who arranged The Old Priest obviously read my mind because the first story is like a perfect sweet onion, with circles of different casings, a ring of happenings that befall a man who is neither wonderful nor awful, all embedded in a story that may turn out to be a novel about a story about a novel concerning an elegant Jesuit who smokes cigarettes with one of those fey ivory holders and drinks perhaps too much very good wine and is an elegant conversationalist: drunk, sober, stoned.

He also has an eye for the young men, and we get to meet two of them here ... one of them such a dandy narrator, neither too worshipful nor too judgmental. I mean, how can you judge a priest who loves you and who you, in turn, one fateful summer evening, you fed him magic mushrooms so that hair sprouts from his hands and face and out his nostrils and drove him half-mad. Though he never blamed you for that crazy-making trip. And who is the seducer in this story, anyway?

§ § § Then there is the last story, "The Burnie-Can." The narrator's mother caught the dinosaur in a plastic laundry basket, and his grandmother saw it too, but when they lifted it up to look at it, it ran away, into the Burnie-Can where they incinerate all the garbage. Later, it was nowhere to be found. No one thought the two of them were lying: "People seemed to like the idea that such a thing was possible, my mother and grandmother were known to be truthful women, and there really was the possibility that they'd seen a dinosaur, or at least a creature that exactly resembled one."

It's a quirky tale. The children not only get to live with this wonder, they also have to put up with their father. At night, "we'd put on their pajamas, each one of us in our own bed, and then my father would come in and spank us."

The spankings varied with my father's mood, but we had one every night, as he liked to say, whether we needed it or not ... When it was over Ailie [his sister] and I would both be bawling our heads off and laughing simultaneously, a sort of emotional confusion that was a cross between the shame that accompanies senseless violence and the exhilarating silliness stirred up by a pillow fight.

This regular abuse comes to be no more strange than seeing a dinosaur in the back yard. The vision of the monster also affects the whole family. Mother stops taking diet pills, grandfather stops shooting rabbits, and father stops beating the two children at night. "The sighting of the dinosaur was somehow restorative, though nobody ever figured out how."

--- Lolita Lark

Poisoning the Neighbor's DogsI stand at the fence, the suit still on my back, the tie at half-mast around my neck. The moon sits on the housetops, yellow and full and low."Your dog," I explain to the neighbor lady. "The little one, there. He barks frequently, disturbs me, my wife. Disturbs the other dogs, for that matter." I smile, try to be polite, off-handed. "You'll have to make an effort to control him. Please."

"Why?"

"Because it's the responsible thing to do. It's the law, anyway."

"Do I even know you?"

"No, but I live here. Plenty of people around here you don't know, I don't know them either. It doesn't have anything to do with what we're talking about here."

"And what is it we're talking about here, stranger?"

"Common decency."

She twists her mouth up, like snapping a change purse shut.

"I need peace," I confess. "My grandmother, she's not well."

"Does your grandmother live in that house with you?"

"No."

We stare at one another.

"It s a dog," she says, and stares through me, a yellow moon dancing in each black eye. "It barks. Bow-wow," she says, and walks away as if that's all anybody would need to know about it. She turns, framed by the light cast down inside her open doorway.

The police, I'm about to say. I'll involve the police.

She flops one pointed breast out of the strapless sundress and wiggles it in my direction. "Who says I'm decent, or want to be?" she asks, calling down the short length of dog-rutted turf. Greatly amused.

--- From The Old Priest

Anthony Wallace

©2013 University of Pittsburgh PressThe Last Folio:

Getting Locked in the Looney WardDear Friends,Folio #40 is sure a good one. I began by reading the Dr. Phage piece about Seattle in the old days and the monster, and was predictably pleased by it.

But there was also much else to enjoy. I particularly liked the review of Hidden America, and the review (and further correspondence) about courthouses in Texas.

The articles on Hitchens and on Larkin's poetry struck a chord --- I too have been thinking about mortality more than I used to. I wonder why?

The hospital advice would have been valuable, if I had followed any of it. I would never have turned up my nose at canned grapefruit or pineapple for breakfast, and I never dared turn down anything all the nurses, technicians, and trolls inflicted on me.

By the way, there was one nurse, a grave, middle-aged Vietnamese-American angel of mercy, who was able to install and remove the dreaded Foley catheter while inflicting only very slight discomfort.

This all reminds me of an instructive story. My friend Arthur's brother once went to a hospital just to visit someone there.

He took the stairs, rather than the elevator, and happened to leave the stairwell at the wrong floor.

After the door closed behind him, he discovered two things: (A) that the door locked behind him, so he couldn't return to the stairs; and (B) that the floor he had inadvertently entered was the locked Psych Ward.

So he made his way to the front, where the main door, also locked, had a window, and tapped on it to attract the attention of the staff, nurses, orderlies, ANYONE.

"I don't belong in here," he shouted at them, "I came in by mistake!" Needless to say, the staffers had heard that one many times before. Arthur's brother may still be there.

--- J. G.

THE NOISIEST BOOK REVIEW IN THE KNOWN WORLD

The Best of RALPH: The Review of Arts, Literature,

Philosophy and the Humanities

Lolita Lark, Editor

NOMINATED FOR

THE 2013 PULITZER PRIZE!

WHAT THEY ARE SAYING ABOUT NOISEA bounty of tasty literary morsels --- acerbic, whimsical, incisive and moving --- spills from this anthology of short pieces culled from the online magazine Review of Arts, Literature, Philosophy and Humanities.RALPH, descended from the much-praised Fessenden Review, is known for lively, opinionated book reviews that aren't afraid to draw blood. An impressive selection is included here, including Lolita Lark's barbed dismissal of Laura Esquivel's Malinche (2006) ("the language heats up and runs off the page and falls into the toilet") and Carlos Amantea's revisionist attack --- who hasn't longed for one? --- on James Joyce: "My own reading of Ulysses is that there are probably 300,000 words too many." There's also a generous helping of poetry, from García-Lorca --- accompanied by a winsome account of an English class entranced by the idea that he had an Afro --- to Joseph Brodsky, Quan Berry and Sharon Olds. There are short stories, including Joyce Cary's droll vignette on the class war between artists and rich dilettantes. And there's a wide-ranging miscellany of nonfiction feuilletons, some original and some reprinted: Javier Marías' evocative biographical sketch of William Faulkner; a snippet of food memoir by M.F.K. Fisher; L.W. Milam's celebration of student diaries as literature; S.W. Wentworth's atmospheric tribute to Mississippi Delta juke joints; a raft of light think pieces on humanistic design and urbanism à la Jane Jacobs; an interview with S.J. Perelman on the horrors of Hollywood; excerpts from Werner Herzog's diary on the ghastlier horrors of the Amazon; a funny take on the similarities between academics and house cats, and grave speculation on the extraterrestrial origins of Bach. Sometimes, as in R.R. Doister's Freudian-pacifist reading of a volume of letters from a West Point cadet, contentiousness tips over into heavy-handed polemic. Still, almost every page crackles with sharp writing and offhand --- occasionally off-kilter --- insights that will fascinate readers.

A thoroughly addictive collection.

--- Kirkus Reviews

Starred Review[WHERE WE'RE AT]This hard-copy version of RALPH comes out two or three or five times a year --- mostly in the late spring, summer, and early fall --- depending on contributions from our readers and the whereabouts of our peripatetic editors.

Like its on-line cousin, it is published by The Reginald A Fessenden Educational Fund, a 501(c)3 non-profit organization.

You are invited to subscribe to keep us alive. All contributions are tax-deductible by determination of the IRS and the State of California.

Correspondence can be sent to

poo@cts.com

Box 16719