and a passionate affection for two or more languages.

A good translator must balancing the needs and music of one language

against the constraints and snares of the original.

Here are a dozen or so we've found

in our recent years of editing this magazine - - -

ones that we've treasured enough to recall for this list.

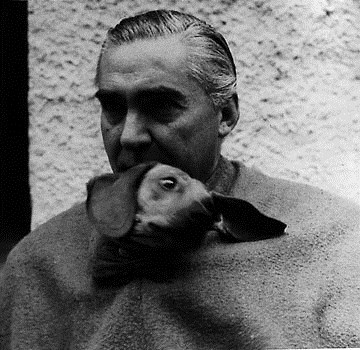

Reflections from the Making of Fitzcarraldo

Werner Herzog

Krishna Winston,

Translator

(Ecco)

After a series of broken arms, dislocated shoulders, snake-bites, arrows from Indians, slides, trees falling, storms, infections, swellings, life-threatening illnesses, lunatic outbursts, machete fights ... finally the actor Klaus Kinski organizes a delegation to come to Herzog's hut. Herzog is "calmly watching the river flow by. I interrupted their preamble, pointing out that I was perfectly calm, much calmer than everyone else out here, so what did they want to say?"

After a series of broken arms, dislocated shoulders, snake-bites, arrows from Indians, slides, trees falling, storms, infections, swellings, life-threatening illnesses, lunatic outbursts, machete fights ... finally the actor Klaus Kinski organizes a delegation to come to Herzog's hut. Herzog is "calmly watching the river flow by. I interrupted their preamble, pointing out that I was perfectly calm, much calmer than everyone else out here, so what did they want to say?"They wanted to talk me out of hauling the ship over the mountain, protect me from my own insanity --- they did not use that term, but their meaning was obvious. They asked whether I could not revise the script so that Fitzcarraldo did not have to pull the ship over the mountain.

I said that we had not really tried towing the ship yet, and I attempted to buck them up in their faintheartedness.

This nut project. And this nut, Herzog, by the majesty of his screwy vision, drags all these people --- hundreds, thousands --- friends, family, associates, investors, Indians, Peruvians, Germans ... drags them into this lorky project, so that it becomes their project, so much so that they come to him, to try to talk him out of this screwy idea, in that land of trees and monkeys and bugs and soldiers and Indians and egomaniacal actors and whores and fighting drunks and paranoiacs: to talk him out of this project, because he is mad to have even conceived it, and, even worse, is madder yet .... no? ... to keep on so that they will too (maybe) have to go ahead and do it with him and go mad too.

It is the way power works, no? There he is, our modern-day Maximilian, there in the director's chair, assuming his own power, swaying his followers into thinking they too can be part of this screwy world of visionaries, those who dare to haul massive boats over massive peaks before the camera (the very one he stole from the Munich Film School; it was his right ... he told them).

And it worked: they bought into his cracked idea, had to watch as the world they thought they were creating slowly spun apart. The demand of destiny; the demand of history.

Go to the complete

reviewThe Guilty

Stories

Juan Villoro

Kimi Traube, Translator

(George Braziller)Get Guilty, (get guilty!) . . . for here you have Hunter Thompson without the drug-stained hyperbole, Thomas Wolfe without the elegant sarcasm, Truman Capote without the self-destruct, Norman Mailer without the drunken brawls, Gay Talese, Jimmy Breslin, Joan Didion ... and Roberto Bolaño. Any writer who can mix iguanas with the drinking habits of Buñuel plus quotes from John Lennon, blended with a fine impatience at the absurd glorification of English ("The planet had turned into a new Babel where nobody could understand anybody else, but the important thing was to not understand anybody else in English") --- anyone who can jumble these wild cards all in one book (and make them work) deserves anything we can give him.And let me offer you my favorite quote from The Guilty. It manages to stuff a certain improbable turn-of-the-century media star into less than 100 words.

I think about O. J. Simpson before the murder accusation, back when he shone as a desperate success known to devour yards on the football field and in ads where he was about to miss a plane. I liked that about airports. They only have internal tension. Everything exterior is erased. You have to run in pursuit of a gate. That's it. Your destination is called "Gate 6." O. J. was made for that, to run far away from intercepted phone calls, broken love, empty glances, bloodied clothes.

Go to the complete

review

The Bestiary

Or, Procession of Orpheus

<Guillaume Apollinaire

X. J. Kennedy, Translator

(Johns Hopkins University Press)

THE CAT

I hope I may have in my house,

A sensible right-minded spouse,

A cat stepping over the books,

Loyal friends always about

Whom I couldn't live without.LE CHAT

Je souhaite dans ma maison:

Une femme ayant sa raison,

Un chat passant parmi les livres,

Des amis de toute saison

Sans lesquels je ne peut pas vivre.Outside these homely verses, there are Dufy's woodcuts. They are thick, gorgeous, perfectly enclosed, sinuous and whimsical. The book design is obviously a work of love . . . leisurely, exquisite. Poems set on the left-hand side; woodcuts are centered to the right, the whole being bound with lavish care.

We've been entranced over the years with the works of X. J. Kennedy, and, outside of merely translating, we detect his fine hand in this fine morsel. It's a book to love, a treasure-trove for people who care too much for great woodcuts, plus cats, dolphins, doves, and rabbits --- not to say grasshoppers, flies or fleas ("Fleas --- friends, even lovers, / How cruel are those who suck / Our blood in loving us, and those / Best loved are out of luck.")

Apollinaire almost got his friend Picasso to illustrate the original edition (one sketch is included in the frontispiece). Thank the muses that the artist opted out. Picasso's animals shown here feel protean, stunted, uninspired. Dufy's cuts on the other hand are gorgeous, make the whole worth it, make life worth it. Fleas, jellyfish, carp, whales and all. [See cunning rabbit above]

The Skin

Curzio Malaparte

David Moore, Translator

(New York Review Books)Malaparte is seated with several Germans, including the vicious Governor-General of occupied Poland, Hans Frank (along with several other high Nazi officials). During the dinner, Frank asks Malaparte directly what he thinks of the dictator. Before he can answer, another guest (a representative of Heinrich Himmler's SS) calls out that "Herr Malaparte has written in one of his books that Hitler is a woman.""Just so," I added after a moment of silence. "Hitler is a woman."

"A woman!" exclaimed Frank, gazing at me, his eyes filled with confusion and worry.

Everyone remained silent, looking at me.

"If he is not quite a real man," I said, "why should he not be a woman? What harm would there be? Women are deserving of all our respect, love, and admiration. You say that Hitler is the father of the German people, nicht wahr? Why couldn't he be its mother?"

"Its mother!" exclaimed Frank, "die Mutter?"

"The mother," I said. "It is the mother who conceives children in her womb, begets them in pain, feeds them with her blood and her milk. Hitler is the mother of the new German people; he has conceived it in his womb, has given birth to it in pain and fed it with his blood and his..."

"Hitler is the father, not the mother of the German people," said Frank sternly.

"Anyway, the German people are his child," I said, "there's no doubt about that."

"Yes," said Frank, "there's no doubt about that. All the people of New Europe, to begin with the Poles, ought to feel proud to have in Hitler a just and stern father. But do you know what the Poles think of us? That we are barbarians!"

"And do you feel hurt?" I asked, smiling.

Go to the complete

review

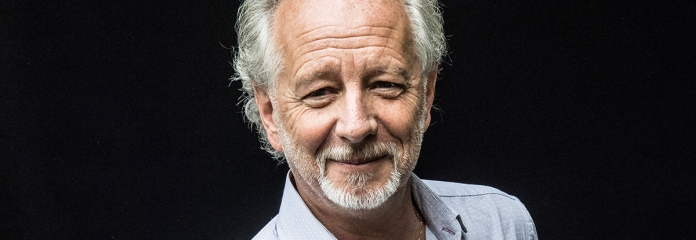

War and Turpentine

Stefan Hertmans

David McKay, Translator

(Pantheon)Hertmans forces reader and hero alike into a new form of war. For never had war been fought in the trenches, moiled with a brand new gestält of machine guns, grenades, artillery, gas, machines, wreck the land . . . along with a new morality, one that led national governments to force war not only on each other, but on entire peoples. A new kind of war where peaceful men could be rounded up from the field and home and shot; a new morality that had never been seen in previous conflicts.In Urbain's early campaigns in Flanders, the soldiers trudged through the "stunning" countryside, where "summer clouds drifted over the waving grain in the distance, the stands of trees in pastures shaded the grazing cattle, swallows and larks darted through the air, sticklebacks glinted in the clear brooks, lines of willows swayed their branches in the warm breeze."

It reminded me of the seventeenth-century Dutch landscape painters, of their peaceful pictures, of treetops painted by the English artist Constable, dappled with patches of light and shadow, of the tranquil existence he had captured on canvas.

And this bucolic otherworldly existence comes quickly to be pitted against a war story.

We could go on to describe Hertman's haunting pictures of trench warfare - - - but I think it is safer to let his words speak for themselves. In two readings [see below] you'll find a special mastery of words that puts us directly in the trenches.

I can tell you as a long-time WWI addict, I have read too many writers who try to capture that particular vision, but Hertman has them all beat. How? By an exquisite blending of art and specificity, in this case blessed with an excellent translation by David McKay.

The writer manages to capture a relentless picture of the contradiction of people raised in civility being quickly transformed as they live among the rats and mangled bodies and soul-wrecking weeks months years of fire-power, chaos - - - ones that left those who went through it mentally and socially crippled for the rest of their days (as was Urbain).

§ § § War and Turpentine was something special for me. It's my job to read and review several books a month. I've been doing this for many years. With this deluge of reading matter, it is all too rare that I have willingly taken up a book, read it through, waited a few days and, at the end of that period, picked up the same book, gone through it, slowly, again - - - enchanted (again!), all the while, trying to figure out how the writer did it.

And I should say, at the end of this, I damn near found myself wanting to pick it up yet again . . . to give it a go just one more time.

Hertman's writing isn't just mastery; it's divine. And it deserves everything we can give it.

Go to the complete

review

The Same Sea

Amos Oz

Translated by Nicholas de Lange

(Harcourt)Amos Oz --- did he make that name up --- is perfectly willing, being a late 20th Century Nabokovian, to play a medley of tricks on us. Like one aperçu, entitled Magnificat, a "Morning of orange-tinged joy" where

The light of the hills to the east cannot keep its hands to itself, shamelessly

groping at private parts, causing heavy breathing all around...Such a fecund day, that the narrator leaves the desk, goes off to work

in the garden, although it is not even six, the fictional Narrator, the whole cast of characters, the implied author, the early-rising writer, and I.

And who appears? The everyone in the book, along with extras --- Albert and Rico and Giggy Ben-Gal and Nadia (from the grave --- along with her previous husband), "my father" (whose?) and Dombrov. Bettina, and "my mother" (whose?) and Dita "stooping and tying sweet peas to canes..." Maria, the Portuguese whore pops up, as do the five Dutchmen who climbed the mountains of Tibet with Rico.

It's like when the play ends and they drop the curtain and all the characters ---- even the ones who have been stabbed or gone mad --- rise up and come out to accept their applause. A lesser writer could never bring it off. For Oz, it's just another fillip, just to show who's boss; all those characters, many or some or none ("the implied author, the early-rising writer, and I") who just might be, but maybe aren't, Oz himself. Nothing so simple, because we may have many characters in search of an author. If there is to be one at all.

§ § § A worthy novelist --- one who has to be worth our time --- must construct a universe enough like our own that we know where it can (and should) go, but, at the same time, must create one original enough and strange enough so he can take it (and them) where ever he wants to, even if it means murdering them, getting them robbed, letting them be miserably sad, letting them be so disgustingly brazen. This Oz pulls it off; knows the dance of the words --- so much so that I caught myself thinking of the writers that in my sixty years have swept me off my feet with their stories and their words and their word-tricks and their daring.

There's Barth and his Floating Opera and Bart-Schwarz's Just and the Unjust and Donleavy's Ginger Man, and Hemingway and Faulkner and Sherwood Anderson and even Sartre himself (in that pretend autobiography, his finest novel, The Word). There's Beckett's Mrs. Rooney, Carey's Gully Jimson, Nabokov's Humbert Humbert and Joyce's Leopold Bloom (and Molly). And now --- for those of us looking for such things --- there's Amos Oz.

Go to the complete

reviewTiger Milk

Stefanie de Velasco

Tim Mohr, Translator

(Head of Zeus)The whole scene is sketched so briefly, so organically, so impressionistically - - - turning neither gross nor exciting nor pornographic but emblazoned with rich detail that hits the reader blindsidedly. While Nini is servicing her man she absently puts on a cowboy hat, thinks "It's actually good that the guy in the wheelchair doesn't have any legs because at least that way he can't get on top of me, in fact he can barely move around at all, which is good." The television is going, running a nature program Terra X and she remembers watching an episode with her father about a circumcision ritual that takes place in "the rainforest where aboriginal boys about the same age as me and Jameelah had to wait in line."They had their hands in front of their balls like in a soccer game when there's a free kick, except that they were all naked and instead of standing in front of a goal they were outside a little tent. Crying boys kept emerging from the tent with blood on their cocks.

Writing like this ain't penny ante stuff . . . and with all the added touches we have here a Hope Diamond stuck smack dab in the middle of the book, a book that can be confusing, confounding, sometimes too much - - - but in the end damn near impossible to put down.

Ask me. I know. I tried several times.

Finally had to finish the son-of-a-bitch at four a.m. with me crawling out of bed at some ungodly hour to pretend to go to work the next day.

Go to the complete

review

Of Kids & Parents

Emil Hakl

Marek Tomin, Translator

(Twisted Spoon Press)In Klánovice, in 1956, the Russian have just moved in, Ivan's father takes ten-year-old Honzo out to "the road that goes from Újezd by the viaduct, along which tanks had been rolling from morning till night for about four days."Grandfather says, "See that? Remember it!" He throws a stone at one of the tanks. But for Honzo, it was the first time he'd seen real tanks. "What a rush! The motors roared, smoke hung above the woods, the tanks rumbled along one after another, and still there was no end to them!"

We stood there until the afternoon. Granddad shook his fist at them but I waved at them, secretly so he couldn't see me.

One threatening, the other waving, the two-in-one, the Janus-face, one mad, another happy, the two conjoined, grandfather-grandson, father-son...

...Father and son, different, perhaps, but revealed here to be cronies, old cronies, who get pissed at each other, open up, shut down, confound us (and each other) with their memories, their tall tales, who can believe Honza's whopper about Johan/Lazarus Batista Kollendero, "who were born in London and they were formed in such a way that Johan was growing out of the chest of his normally developed brother, so throughout their lives they were looking at each other's faces. Lazarus was the one with the legs so Johan had to go from one party to another against his will."

Apparently they always argued about it, and Johan would end up offended, staring at the ceiling all night, while Lazarus would fool around, tell jokes, and in between he'd reason with his brother in a quiet, friendly voice.

Weird, wonderful, wonderfully-horribly joined, like all of us, with those who bore us, who bear us, like Ivan and Honzo, the two of them filled up with their stories, filling us with their stories, there on the streets of old Prague. The memories out of their lives (past and present), the common history of two who have several things in common: memories, father and son, joined-at-the-hips.Some may be false, some maybe not; but mostly stories out of our lives minted by Emil Hakl come as pure gold, as rich and as good as it gets.

Go to the complete

reviewThe Milli Vanilli Condition

Essays on Culture in the New Millennium

Eduardo Espina

Travis Sorenson, Translator

(Arte Publico)

- The coming of cell phones makes us all "a universal witness, a thief of instants with visual posterity included."

- Since Japan is surrounded by water, it is mysterious. "Water wants to get in so that it can get to know it." Thus tsunamis.

- During one tsunami, homes --- made of wood --- were "floating by, on their way to forgetfulness, as if asking where their home was."

- Espina lived in Texas. On September 11, 2001, "People spent the day watching television, since there is where reality goes first."

- On September 12, "the destruction of the World Trade Center could be seen commercial-free at all hours and on all channels." Everything was then covered in flags. "Just as with mushrooms after the rain, they were everywhere. The era of the flag had arrived. Houses and other buildings had grown flags during the night, even though no one had watered them."

- Serial killers may also be "necrophiliacs." Jeffrey Dahmer, according to his lawyer "was a necrophiliac who loved to have sexual relations with non-loving objects." Espina avers that he might be the "Most popular serial killer in the history of pop culture."

- He also claims that Dahmer could be seen as a "cereal killer" because, like other of his cohort, he was "capable of eating their prey during dinner or breakfast (in this regard Dahmer was very democratic, since he would eat his victims at any hour of the day.)"

- Espina is a poet, and he gives live readings. When a fan came up at the end of his presentation, saying that "listening to me has made him want to write, I feel compelled to invite him to plagiarize me," because then Espina is "the writer who has spawned the impersonation of a fellow human being." He points out that, according to Paul Gauguin, "Art is either plagiarized or revolutionary."

Go to the complete

reviewMemoirs of a Revolutionary

Victor Serge

Peter Sedgwick, Translator

(University of Iowa)

I began to feel... this sense of a danger from inside, a danger within ourselves, in the very tempers and character of victorious Bolshevism. I was continually wracked by the contrast between the stated theory and the reality, by the growth of intolerance and servility among many officials and their drive towards privilege.

This is Serge's first hint that he and the thousands of loyal radicals who participated in the early days of the Russian revolution were witnessing an unexpected change:

The maddening atmosphere of persecution in which they lived --- as I did --- inclined them to persecution mania and the exercise of persecution.

Only a few of the "old Bolsheviks" saw the drift that the country was taking: a new and stifling bureaucracy, repression, their fellows murdered or sent to labor camps or expelled from the country. And when Stalinism took hold, there was always the question (one that was to emerge again and again, most of all with the trials of 1936-37): how could Serge and the true believers stay loyal to the dream that was being so elegantly poisoned?

The answer is strange to us now, but was not so strange in 1927 or 1931 or even 1935. With all its malfeasances --- "the Terror," a revolutionary experiment hijacked by the bureaucrats and thugs (the Cheka, the G. P. U.) --- still, after all this, it was the only Revolution going.

The old Bolsheviks and anarchists staked their hopes on the export of revolution to France, Germany, Italy, Hungary, Poland, China. Once the people's government took hold in those countries, the pressure would be off; then, it was thought, Russia could resume its course towards being the true revolution --- democracy of the workers, freedom of speech, the ownership, by the people, of the very means of production.

Unfortunately, with the help of the United States (most diligently Herbert Hoover), England, France, and those who had manufactured the time bomb called the Versailles Treaty, the baby was murdered in the crib. Russia was forced to go it alone.

And despite the horrors Serge saw around him --- friends being exiled, murdered, sent to the concentration camps, hounded to death, suicides (the number of suicides among the old radicals was astonishing) --- despite the secret police, the disavowal of Trotsky, "the sordid taint of money," and what he calls "The Soviet Thermidor" --- it was still, still, the only game in town.

Go to the complete

reviewThe Museum of

Unconditional Surrender

Dubravka Ulgrešić

Translated by

Celia Hawkesworth

(New Directions)Dubravka Ulgrešić is fascinated by angels, angel wings, photographs, photograph albums, soot, turning apples into roses, notebooks, threads, her mother, and those glass balls that you shake up and the little village comes to be inundated with snow.She also hangs out with strange and wonderful artists, such as one named Sissel:

Obsessed with her own sense of space and her place in that space, Sissel has sent a quotation from Winnie the Pooh (where Winnie, having found the North Pole, asks Christopher Robin whether there are any other poles in the world) to many embassies all over the world, asking them to translate the quotation into the language of their country. Sissel now possesses a collection of translations of the same quotation in many of the world's languages. In the original the fragment goes: There's the South Pole, said Christopher Robin, and I expect there's an East Pole and a West Pole, though people don't like talking about them.

Dubravka Ulgrešić is an original and funny and weird writer. She has compiled "chapters and fragments" in The Museum of Unconditional Surrender and she wants us to think of them as being not unlike the contents of the stomach of a walrus, named Roland, of the Berlin Zoo, who died in 1961.

A pink cigarette lighter, four ice-lolly sticks (wooden), a metal brooch in the form of a poodle, a beer-bottle opener, a woman's bracelet (probably silver), a hair grip, a wooden pencil, a child's plastic water pistol, a plastic knife, sunglasses, a little chain, a spring (small), a rubber ring, a parachute (child's toy)

etc etc. "If the reader feels that there are no meaningful or firm connections between them, let him be patient: the connections will establish themselves of their own accord." She concludes, archly:

The question as to whether this novel is autobiographical might at some hypothetical moment be of concern to the police, but not to the reader.

§ § § We might dispute that this is a novel --- at least in the classical sense. We would rather think of it as a long free-verse narrative --- or even a dramatic poem. The subject is the confusing, violence-

besotted, object- acquisitive, wonderfully literary western world in all its strangeness. Symbols appear and disappear as if by magic; themes crop up, often unexpectedly --- then (at times) sentences or ideas will be repeated exactly (or almost exactly) as they were before. For instance, crumbling the air with her toes is a charming phrase that we meet early on. Then we get, at random, the following cinematic scene, featuring the author's mother in her apartment (presumably back in the former Yugoslavia, where Ulgrešić grew up):

She turns off the television, goes lazily to the bathroom. There she sits on the toilet for a long time, crumbling the air with her toes, urinating. In the half-darkness she listens to her own sound...

From the bathroom she goes to the kitchen. She doesn't turn on the light. She opens the fridge, stares at the illuminated display, looking for something. On the white wire shelves are a yogurt, a carton of milk, a little piece of cheese --- a mouse's supper. She closes the fridge, without taking anything.

Go to the complete

reviewPopular Music from Vittula

Mikael Niemi

Laurie Thompson,

Translator

(Seven Stories Press)It is the story of Matti and Niila growing up in Pajala --- a tiny town in Sweden, close to where it touches Finland. It is cold and dark, but the people in Stockholm are bringing in electricity and paving the roads and somehow the two boys come across a record of roskn roll musis with four young men from England singing Ollyu nidis lav and Owatter shayd ovpail. The Beatles --- and later Elvis --- come to northern Sweden.If this is beginning to sound like an ice-clogged Our Town of the 60s, don't you believe it. There are drinking parties where young men speak only in vowels and wet themselves. There are funerals where several hundred heirs fight viciously over the spoils. There is a ghost of grandmother who haunts young Niila until they face her one night and, oh, cut off her penis and bury it.

There is fumbling love with a black-haired beauty in a hot-wired Volvo, a sauna that gets so hot that only Matti survives ... to fall to the floor, puking (which set me off again). This is Lake Woebegone with nuts, a Jean Shepard never-ending story set in the icy tundra of the northlands instead of Jersey City.

Go to

the complete

review

The World of Yesterday

Stefan Zweig

Anthea Bell, Translator

(Pushkin Press)It was such a balmy world back then, back before they came along and started their wars.From the end of the Napoleonic era until the assassination at Sarajevo, the world according to Zweig was blissful, innocent, glorious. He and his friends would argue poetry and music and art in the pre-WWI coffee houses of Vienna. They would skip classes to read Rilke, listen to Schubert, memorize Goethe, declaim Shakespeare, study the newest "feuilletons." Then came the General Mobilization of 1914 ... which many of them cheered.

During the hostilities, Zweig worked at the Austrian War Archives, and his journeys of research into Galicia and points east led him to travel on troop trains filled with the wounded and dying. It made him a life-long pacifist.

Afterwards, he wrote novels --- Amok, Because of Pity, Fantastic Night were some of the most famous --- and he tells us that his works "were translated into French, Bulgarian, Armenian, Portuguese, Spanish, Norwegian, Latvian, Finnish and Chinese." Through this period, until the end of his life, he longed for the lost Edwardian times ... where a Viennese coffee house was "the best cultural source for all novelty."

Then there are his friends. Rilke, Rodin, Yeats, Gorky, Toscanini, Anatole France, Paul Valéry, Romain Rolland, James Joyce, who, he writes, personally loaned him a copy of Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man..

And then there is Freud:

The friendly hours I spent with Sigmund Freud in those last months before the catastrophe showed me ... how even in the darkest days a conversation with an intellectual man of the highest moral standards can bring immeasurable comfort and strength to the mind.

The art of Zweig is such that we don't blame him much at all for dropping their names ... only feel a piercing envy that he could know such characters, can call up the memories so easily: "I once met G. B. Shaw at Hellerau ... [H. G.] Wells had visited my house in Salzburg."

Then there was his close friend and collaborator Richard Strauss: "He sits down at his desk at nine in the morning and goes on composing exactly where he left off the day before, regularly writing the first sketch in pencil, the piano score in ink, and going on without a break until twelve or one o'clock." The composer, he reports, may then play Skat --- a card-game --- in the afternoon, and after dinner, go off to conduct at the Opera House in Salzburg. One of the reasons we can't stand Strauss' works --- spare us "Thus Spake Zarathustra" --- has to do with his metronome-like ability to pour out such heavy scores without passion: "He is never nervous in any way" reveals Zweig ... and it shows.

Go to the complete

reviewTelevision

Jean-Philippe Toussaint

Jordan Stump

Translator

(Dalkey Archive)Our hero tells us he is going to give up television. At least once the Tour de France ends. Presumably this will help him on his research in Berlin, for which he has been given a hefty grant. The subject? Hold onto your hats:It's 1550 in Augsburg. The painter Titian has been assigned to paint a portrait of the Emperor, Charles V. In his studio, one day,

Titian changed his mind, deciding to switch to another brush and add a golden highlight rather than a touch of white, and let his brush slip from his grasp. It fell through his fingers and landed at the emperor's feet. Dispensing with the customary greetings and reverences, the two men exchanged a glance of tremendous intensity. The brush lay on the floor at their feet, a tiny gold dot at the tip of its fine, contained flame of hairs. Inclined, its colored point glistening with oil, the brush lay on the marble, and no one in the room made a move. Already the muscles in Titian's back, shoulders, and arms were readying the gesture with which he would bend down and pick up the brush, but Charles V acted first, stooping down to retrieve the brush and return it, thereby implicitly recognizing the precedence of art over political power.

Television is positively bustling with strange-

serious- ridiculous stuff like this. First off, there is this bizarre picayune study project of a single moment plucked from the 16th Century, narrated so meticulously, so minutely, that it reminds us of 16th Century portraits, with all their picayune details. Then, there is the day-to-day in the Berlin summer of this Titian dropped-paintbrush student. For example, our hero tells everyone that he has given up television, only to find everyone else saying "I hardly watch it either." Then he promises to care for the upstairs neighbor's plants while they are on vacation, but he forgets, lets them all die (helped along by his stuffing a rare fern into the refrigerator).

He gets lost in the Dahlem Museum, but ends up in a deserted guards' watch station, in front of dozens of closed circuit television screens, watching (on tv!) other museum-goers viewing paintings. He gets lost in Berlin, in the Rilkestrasse (where else?) looking for a lady who is to take him for an airplane ride; he ends up in an apartment where one can look out the window and see countless apartments with countless televisions blaring away, all mostly on the same channel.

And it was then, still distractedly watching those glowing televisions in the windows of the building across the way, that I was struck by the presence of a television glowing all alone in a deserted living room, with no human presence visible before it, a phantom television in a sense, disseminating images in the emptiness of a sordid living room on the fourth floor of the building across the way, with an old gray couch half visible in the dimness.

Go to the complete

review