The Tenement of No. 55 Dropsie Avenue seemed ready to rise and float away on the swirling tide, "Like the ark of Noah," it seemed to Frimmie Hersh as he sloshed homeward.

It's all there. Tenament. Rain. Slosh. Tragedy. Loss. "All day the rain poured down on the Bronx without mercy. The sewers overflowed and the waters rose over the curbs of the street."

"This was the day Frimme Hersh buried Rachele, his daughter." Years before, Frimmehleh had been a child trying to survive the pogroms in Russia. With help of relatives, he had arrived in New York direct from the town of Piske, carrying his contract with God in his pocket ("I'll follow your rules if you let me survive.")

Frimme had found shelter in the Hassidic community, was greatly beloved by the old and the infirm, and ultimately, inevitably, someone even left a babe on his doorstep - - - the girl Rachele, who he cared for greatly, raised to young adulthood.

When she died at sixteen, he said, "No! Not to me. You can't do this . . . we have a contract," and, shaking his fist at the sky, he vowed vengeance. (On god? Quite a challenge.)

He borrowed some bonds from his synagogue, without permission, and began his new career as a slumlord, which we get to follow in all its glory: "But what about Missus Kelly? She's on a widow's pension from Ireland!?" "No exceptions!" This is Eisner's "comic" hero.

According to McCloud, it was a new art form. A Contract with God was published in 1978, under Eisner's own imprit, The Poor House Press. It was a comic book story - - - what we now know as a "graphic novel" - - - in the old form: that of Batman, Superman, Plasticman, the ones that we used to steal so diligently from the corner Rexall's drugstore.

McCloud claims that it existed in its own continuum, patiently waiting for the rest of its kind to quietly arrive - - - by the thousands as it turned out - - - on the shelves of North American bookstores. Eisner thus leads the rest of us. presumably. to Robert Crumb, Mr. Natural, Zap Comix, the Furry Fabulous Freak Brothers, Fritz the Cat, Gilbert Shelton, Art Spielgelman, Jules Feiffer and the mangas from the far East, like Ichigo Kurosaki's Bleach, The chronicles of Soul Reaper.

§ § § The critics of his time loved The Contract with God. John Updike said, "Eisner was not only ahead of his times: the present times are still catching up to him." Kurt Vonnegut stated that The Contract was "harrowingly magnificient." Turns out that Frimme's loss reflected one of Eisner's own. His daughter, Alice, died from leukemia at age sixteen. "Many of us didn't even know the truth beyond occasional whispered rumors until a new century began and the old man finally opened up," McCloud tells us.

Maybe, because it is classic, with such classic lines (visual, oral, spacial) we should resist any criticism. Forty years ago, the divine - - - as well as divine cynicism - - - existed in a somewhat more morbid form. They always taught us that you didn't make contracts, much less argue with (or even name) the great Unnamable. I mean, what do you say to the one who tells you - - - not accepting nor expecting any argument - - - "I Am What I Am?"Such a self-proclamation presents us a rather uncertain bargaining position on our part. And if she who made me wants to take me (or any part of me) back, who am I to complain, much less shake my fist at the monsoon clouds?

But there's something else going on here, and it casts a shadow over this picture of a man ahead of his time. It has to do not with The Contract but with Eisner's story third story - - - "Super."

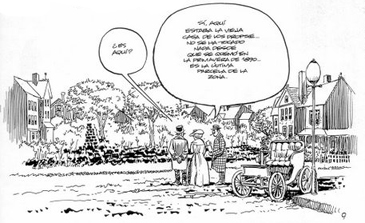

Picture Mr. Scruggs, at 55 Dropsie Avenue, snarling dog on leash, shaking his fist at the quivering tenant. "I'm running this building, Mr. Levinsky! And I'll decide when things need to be fixed." He is the super, after all . . . and, for some reason (was Eisner psychic along with his other problems?) - - - the trembling Mr. Levinsky looks too much like another of our comic books heroes: exactly as Robert Crumb would draw Robert Crumb.

In "Super," we get Eisner's uncomfortable lesson on power:

Between replying to bitter complaints, the nagging the muttering behind his back, he was left with little else but remoteness to defend his dignity and promote his authority.

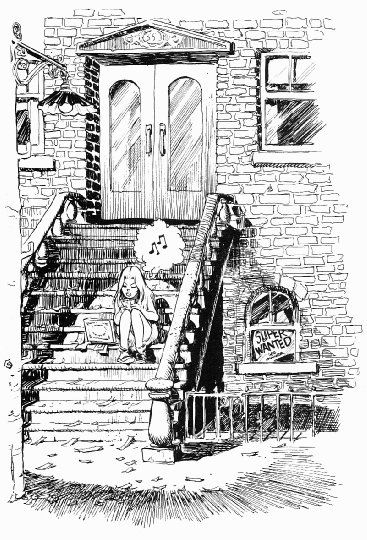

Nothing to bring him down. Except a tenant. Or rather the daughter of a tenant.

Her name is Rosie. Eisner paints her with a very cynical face. Pooched lower lip, cold eyes - - - as she says, "For a nickel, just one look." After Scruggs looks, she says, "That's enough . . . gimme!" Then she grabs his box of money, poisons his dog, and runs out the door.

And when he catches her in the alley, she says - - - same cold look - - - "If you hit me I'll tell on you." (One neighbor is seen commenting out her window: "Steam he don't send up . . . but little goils - - - he beats up.")

It's a very bitter eighteen pages. No, it's worse than that. It says, in effect, no redemption, no hope, no love, no compassion. Only raw lust and raw cynicism on both parts. It tends to temper for some of us any affection that others may shower on Eisner.

It is one thing to be bitter.

It is quite another to be unforgiving.

Of the gods or anyone else who happens to be hanging around nearby.

--- Pamela Wylie