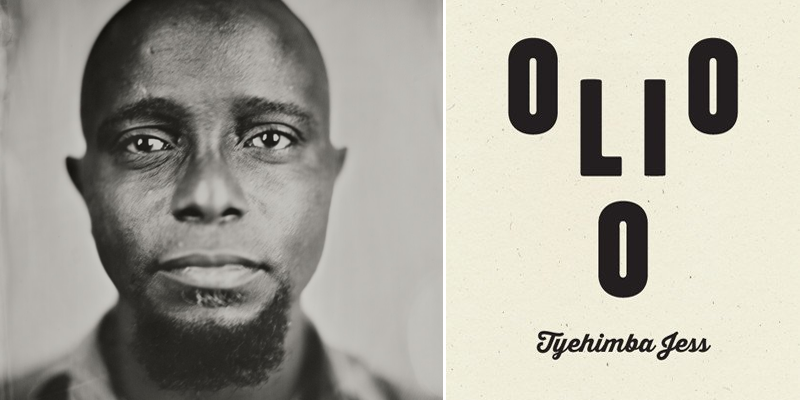

Olio

Tyehimba Jess

(Wave Books)

I remember the word "olio" with fondness, because it was the name of our high-school's yearbook. Only before our time, someone with a certain droll wit had named it "olia podrida." Which means, roughly, "rotten left-over hash." It also might have been the proper title for the title above. It's a rare, lapidary look at America's unloveable gift to all of us from our decayed past - - - slavery.The power of Olio is that it forces us not to look at the cynical acceptance of slavery by our great-great-grandfathers, but to observe the heroism of people surviving its machinations with their dignity intact. And we find here people who were forced to use many devious ways to escape.

Take Henry "Box" Brown. While a slave he mailed himself from Richmond to Philadelphia "in a box, three feet, one inch long, two feet wide, and two feet six inches deep."

Twenty-seven hours he was closely packed within these small dimensions, and was tumbled along on drays, railroad cars, steamboat, and horse carts, as any other box of merchandise would have been, sometimes on his feet, sometimes on his side, and once, for an hour or two, actually on his head.

One contemporary, Samuel J. May, wrote, "Is there a man in our country, who better deserves his liberty? And is there to be found in these northern states, an individual base enough to assist in returning him to slavery! Or to stand quietly by and consent to his capture."

May was using case history to indict the notorious Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, passed by a congress as boorish as our own. It required that all escaped slaves were, upon capture (in the north or in the south), "to be returned to their masters and that officials and citizens of free states had to cooperate in this law." Abolitionists nicknamed it the "Bloodhound Law" for the dogs that were used to track down runaway slaves."

Olio here concentrates on one man in one escape, but all these pages are filled with stories like this, and, moreover, poems - - - called "Jubilees" - - - praising those who used ingenuity and pluck and song to overturn a system that had a built-in curse.

Pa'd whispered, They gone sell

me in the morning, son. By five years old

I was orphaned. By nine, it was war.

I got conscripted by the Rebs. They told

me Yanks weren't fit to live. That they fought for

raping and pillaging nigger skin. That

free will was just a trap. A deck of cards

stacked against black.Or this by Green Evans,

My brother and I got blood-hounded

hard when we escaped ol' master. By then,

we too had heard Union bugles blow. We knew

it was the fall for Jericho. My friend,

can you imagine how it must feel to

finally own you own skin? Arms? Legs? Eyes?

To bellow with your own mighty light?Or this from Maggie Porter:

They blast through our throats, beating injustice and those who'd seen us bent to ignorance - - -

like when the Ku Klux burnt down the schoolhouse

where I taught one Christmas. They couldn't stand

to see us rise up from plantation dust. How

they must have angered to see me teach again . . . We won't stop our music until we're thruth

tearing down Jericho's walls with our truth.§ § § Tyehimba Jess has built startling facts and figures from 150 years of the American peculiar system of capital accumulation by means of the bodies of men and women. A typical plantation's net worth was computed in the number of souls owned. Discovery Education computes that a healthy young slave just off the boat from Africa "was valued at about $21,000 in today's dollars." That same slave, if he or she were still healthy, could be sold again. "In the years right before the Civil War, such a slave might bring nearly $2,000 - - - about $40,000 in today's dollars."

§ § § This volume is like a good novel. The themes begin to accumulate at the very beginning, and quickly bring the reader along, inciting wonder at the art of those who defeated slavery by slipping around, through or under it.

Masks? Minstrel shows were immensely popular in the late nineteenth century, usually white men whose faces were painted with black cork. In ironic contrast, there was one "Black Patti" - - - leader of "her eponymous Troubadores." She was an opera singer, but

Of course, even when she did belt out some opera born outside of this country's peculiar history, she'd still have to come right back down and weave her way out of the cakewalk of blackface and jim crow. Every evening, she'd waltz all proper out of the spotlight - - - and then let the okie doke shuffle and that coontalk grin take over the stage. You know - - - the circus they was all comin to see. All of 'em - - - black and white and every shade in between - - - came because of her name, wantin to see the famous Black Patti herself. And just about as many stayed on to feel the glow of those minstrel shines. What is a coon show, anyway, but one poor devil puttin on a mask another devil willin to pay to see?

Masks were central to the ability to survive, allowing one to show exactly what one wants, to face the world in a predetermined stance. And Masks are central to Olio, right down to the cover, a stylized simulation of the human face, a cover face à face with the face of the author.

Black-face, revolt concealed as cooperation, and the centrality of song is as much of this book as the shameless reworking of vocabulary that fed coming freedom.

There is a central character, Julius Monroe Trotter, who came, in the early part of the twentieth century to interview dozens of people who knew Scott Joplin before he died in 1916.

Julius' story is as poignant as that of the man who inspired him. At the beginning of Olio we are introduced to him thorough a letter he sent to W. E. B. Du Bois. He tells of his induction in the all black 369th regiment, the "Harlem Hellfighters" of World War One:

I marched with my fellow fodder in the great parade down 125th Street and onto the boat to France, where we climbed down the desperate trenches of Marne, Champagne, Belleau Wood and beyond. Even as I continued to keep Mr Joplin's music fastened hard in my heart, it was blasted to and fro in my brain by mortar and Mausers. It was crushed by the sight of men blown to bits. It was singed by the sound of trumpets bent to war.

Trotter fought the Germans, and lost his face. The French medics fitted him with a prosthetic mask to protect him from the fear of others when they see a man divested of his identity, not so different from that of a slave who loses his identity when bought or sold.

The six interviews Trotter conducts here ended up in the Du Bois estate, and constitute a rich back-and-forth among others he came to know who lived by their wits. Take this interview with John William "Blind" Boone in 25 October 1925.

I interviewed Mr. Boone in the piano room of his spacious abode in Columbia, Missouri. Mr. Boone was well attired, and sat ever near to his ornate Chickering Brand piano with which he punctuated our discussion.

Thank you for your time, sir.

I wouldn't refuse a man who's come such a long way just to talk about ragtime. Besides, I can tell by the sound of your walk and the shake of your hand that you're carrying something heavy you need to put down. Or maybe you need help carrying it. And it's about music, eh?

Yes, sir. Scott Joplin in particular.

Scott Joplin. (Sighs) One of the best. Before we begin: You sound a bit muffled. You intend to interview me with that cover on your face? Why you speaking through a mask?

It's a prosthetic, sir. A loss was suffered in battle.

I see . . .Well now, don't we make a pair. Two halves makin up a solid whole. I got no eyes, but all creation sees my face. You got vision, but most can't see past that mask. Folks know you, but they don't know you, and you're privy to a secret part of them just by how they act around you. And me, I somehow come to know every soul I meet. I can remember what they said ten years ago like it was yesterday, down to what we ate for dinner and desert. Everything except their face.

(Laughs) Don't worry. You the same as anyone to me, friend. I see past that mask of yours just like everyone else's.

Well, once again, thank you for your time, Mr. Boone.

And you going around asking folks all over, tryin to get Joplin's story, huh?

Yes, sir.

(Laughs) Well now. Looks like Scott got himself a straight man.

Excuse me?

An interpreter, son. An interlocutor. A straight man. Someone to guide us through the forest of tall tale and superstition. Sort out the foolish from the fact. That's what I smelled on you when you walked through that door. The scent of someone in search of a story.

Mr. Boone, I rather don't think of myself as a performer in a minstrel show.

Most don't. But fact is that the minstrel show is only a grin or a shuffle away from any living Negro trying to tell his own true, full story and survive in the world. The true story, now. There's a way to tell it straight and true, so that the joke's not on you, but all around you. The whole round riddle of it: how you came to be where you at, and what folks told you along the way that got you there.

Well then, sir. I trust that you may be able to help me get your own true thoughts on Mr. Joplin.

That I will, my man. The true story, 'cause I remember it all . . . exactly. Now, what is it that you would like to know?

§ § § Here we have a minuscule fragment from an astounding collection, a book filled with dialogue, song, wit, and woe: a compleat manual on the lives of those who were forced to live by their wits.

Intermixed with this is occasional tomfoolery, Jess' obvious genius, sketches, dialogue, pull-outs, background, and odd poems split down the middle. Jess notes at the bottom of one of his "split poems": Mr. Henry "Box" Brown blackens the voice of poet Mr. John Berryman's "Henry" from The Dream Songs and liberates him(self) from literary bondage.

PRE/FACE

BERRYMAN/BROWNThe poem then, Let me say,

whatever its wide cast of characters, despite loss . . . I won my life. This story - - -

is essentially about how a slave steals back his skin:

an imaginary character smuggles loose like I did. It lives on,

(not the poet, but through words - - - and

not me) free I'm

named Henry, "Box" Brown. Ain't

a white American masking my truth: one day

in early middle age, I delivered myself

sometimes I ache

in my

blackface, love for

who has suffered . . . those left behind.

an irreversible loss . . . Berryman can't talk for them,

and talks about himself . . . can't tell my tale at all.***What we have here is three poems in one . . . John Brown's words interspersed in the middle of Berryman's poem, making a third poem cut and conceived by Jess.Olio is filled with these tricky and winning devices, including a demonstration on how to wrap words to the point of making them not only folded, but torus, and mõbius. As the blackface is part farce, part trickster, part twister, it's also a mind-bender loaded with heavy humor and a dose of mockery. This very volume is a generous gestält of the tools used by those hiding in blackface in plain sight.

--- Lolita Lark***Reviewer's Note:

I tried to space this poem as did the author (and typographer)

on the page. I failed. If you buy the book - - - do it - - -

you will see how they have arranged it as the perfect split

between Brown and Berryman.