jam-packed with works that had appeared

in this magazine over the previous twenty years.

It was entitled The Vivisection Mambo,

got terrific reviews at Kirkus and Booklist,

and promptly dropped into the void,

that dark graveyard of terrific

books that never made it.

Still, we've never given up our role as the doyen

of modern verse, have continued to publish

what we believe are some of the best poems online.

Here's a catch-up - - -

those we've featured in the interim.

< 'The solution to pollution is not eating spiders'

--- Newspaper headlineThe solution to pollution is to stop ingesting spiders,

Just say no to the arachnida that copulate inside us,

How they pullulate and ovulate, the octopod articulate,

Auriculate, testiculate and oft times unguiculate,

The narrative of nightmare and the stuff of holy terror,

They're the creatures that convince you all your life has been an error.

So you're sicker than a parrot and you wish that you were dead?

Just you wait till they migrate and drill themselves into your head.

Creepy-crawly, creepy-crawly with a subtle sideways motion,

Some detestable detritus from the bottom of the ocean,

Something feral, fanged and furry with a flush of nasty habits,

Now they're ferreting like ferrets, now they're rabbitting like rabbits,

Now they're occupying occiputs and populating dreams...

Eating spiders isn't nearly as attractive as it seems.--- John Whitworth

From "Qualm"

Dictation Furthermore, there are occasions when

Furthermore, there are occasions when

I wish to raise the windowsill

and shout obscenities into the street,

loudly and with violence.

Of course I never do. Full stop.

Instead I offer my mistakes to be plucked out

like silver hairs by Mr. Collinson,

a small god dressed in loafers

and a double-breasted suit

who lodges in my ear all afternoon

dictating minutes of The Management Review.

But I would sooner tell youhow the sky sheds drizzle, sheer as iron filings

on a group of children shambling from school;

how I weep inside the porcelain confessionals

admitting my desire to wound, and grievously,

the hairsprayed middle manager;

how I hope to find my guardian angel

crouched inside the stationery cupboard

counting paperclips, ready to unfold

her giant wings and fly me

past the awkward fellowship of office drinks,

past desks made homely with a snapshot of the kids,

beyond the Seventh Floor executives

resplendent in their offices like cardinals,

up through stratospheres of city smog,

up into space --- the boundless silence

where she'll let me go ---

a million memos floating free,

the telephones of earth a distant memory.--- From Sunday at the Skin Launderette

Katryn Simmonds

Seren (Poetry Wales)

Dear ProfessorLet me explain my lengthy absence ---

My entire family got food poisoning,

myself included. We had eaten rotten

fish tacos, old bad cod, I've never been so

nauseous, the house wouldn't stop

spinning, wouldn't stop shuffling

its windows, I was gushing from

I'll spare you the details. And Grandma

shutting down, hallucinating, said the world

was pixilated. We rushed her to St. Mary's

on a flat tire, no spare in the trunk,

a burst of sparks as the screaming rim

scored the road like a pizza cutter.

They plugged her in, her monitor drew

neon green mountain ranges. Strange,

you'd think they'd have Internet access

there, free wi-fi, a wing in the hospital

to check one's email. Odd, too, no

connectivity back home, no electric blood

sluicing through the wires, a hitch

in the system, some inexplicable glitch,

impossible for me to get a hold of you

until now, two weeks after the due date.

l'm sorry. And sorry I missed class today,

another flat tire, stupid overturned

box of nails on the freeway, I hissed

for miles, the car listed, such a headache,

and still queasy from the tacos. Please

consider all this when grading my essay

(see attachment). Please excuse any typos

or logical fallacies, my mind has been

elsewhere: Grandma's mountains

stretched flat. Her green horizon. I want

to live forever. I want to pass your class

and graduate, get a gig, marry some hottie,

see the world, drive until my wheels

come wobbling off, and keep driving ---

but first I need to pass your class.

No pressure. Honestly. No pressure.--- David Hernandez

From Wide Awake:

Poets of Los Angeles and Beyond

©2015 Pacific Coast Poetry SeriesGo to a review of the

bookOrdinary SexIf no swan descends

in a blinding glare of plumage,

drumming the air with deafening wings,

if the earth doesn't tremble

and rivers don't tumble uphill,

if my mother's crystal

Vase doesn't shatter

and no extinct species are sighted anew

and leaves of the city trees don't applaud

as you Zing me to the moon, starry tesseræ

cascading down my shoulders,

if we stay right here

on our aging Simmons Beautyrest,

dumped into the sag in the middle,

that's okay.

You don't need to strew rose petals

in my bath or set a band of Votive candles

flickering around the rim.

You don't need to invent a thrilling

new position, two dragonflies

mating on the wing. Honey,

you don't even have to wash up after work.

A little sweat and sunscreen

won't bother me.

Take off your boots, babe,

swing your thigh over mine. I like it

when you do the same old thing

in the same old way.

And then a few kisses, easy, loose,

like the ones we've been

kissing for a hundred years.- - - Ellen Bass

Go to a review of the

book

Regret

(Poem on the Death of Elvis the Cat)Elvis won't eat. He's twenty years old. Mostly he sleeps,

staggers off to the litter box, drags himself back - - -fur like a thrift-store suit, rumpled, bagged at the knees.

You've been avoiding the trip to the vet - - - the news will be bad."For Christ's sake," your wife says on the third day.

"I can't stand it." So you grab an old sweater, wrap upthe shivering cat, put sweater and cat in a cardboard box.

He hates the car, still has enough chi left to yowl the whole way - - -he knows where he's going, knows he's not coming back.

The office is bright, toxic with Lysol, sharp funk of animal fear.You hold the box on your lap. Elvis papoosed in your sweater,

panting, eyes dull. Whatever love is, it's not what you feelfor this cat - - - sprayer, shredder of chairs, backhanded gift

from a breakup - - - your ex moved in with her girlfriend,no pets allowed. Two seats down a woman shushes

her mutt: it yaps at the end of its leash. Then it's your turn."Good night, old boy," the vet says. The needle slips in.

Elvis sighs, his flat skull in your hand. He purrs for a secondor two and then stops. You can't love what you don't love;

you try to be kind. But the sweater is Brooks Brothers,cashmere. You've had it since grad school - - - it's black

and still fits. Not really thinking, you lift the dead cat,unwrap the sweater, lay the lank purse of bones

back in its box. You leave him there at the vet's - - -no little backyard service for you. You drive home.

Your wife says, "That's it?" and you nod.There's not much that keeps you awake anymore:

the future all rumor and smoke, a bus that never comesuntil it comes - - - the past already published, out of your hands.

So what do you do with it, then? Shoved into the closet,moth-reamed, way in the back. Crouched in its dark corner:

the thing that still fits. The thing you can't throw away.--- Jon Loomis

©2015 Poetry Daily

My Brother is BusyMy brother is busy packing for jail. I sit on his bed and watch him

set aside a blank notebook, pen, copy of Genet's "Thief's Journal."

Jean Genet did some of his best writing in prison, he tells me.I want to say, he was a glamorous playwright in Paris, France,

you are a drug addict-sometime singer in Bakersfield, California.

Jean-Paul Sartre will not be coming to your rescue. Instead,I say, I'm not sure they'll let you have that fountain pen.

The romance of jail, of positive spins, has captured my brother

in the June-addled San Joaquin Valley. He's hoping that this timethe judge will sentence him to a prison rehab unit. I'm done caring

what he hopes, or so I think, only here to pick up what's left of mine

that he hasn't pawned, then return to school. My first summeron parole from stomach pumpings, bail bondsmen, high dramas

in the house on Occidental Street. I can write with anything. He removes

the pen from the stack. I can write in dust, I can write with my mind.Here is the part where the sister laughs, where she may later wish

for a chance at revision. We don't know it, but this is our last conversation.

My brother will be dead in two weeks, I'll be in some other citywhen he overdoses on downers as our parents drink double

vodka tonics in another room. I'll get a call at 2 am. Someone

will say, This is your mama speaking. And I'll answer, Who?--- Candace Pearson

From Wide Awake:

Poets of Los Angeles and Beyond

©2015 Pacific Coast Poetry Series

When Tony Hoagland Says

My Maternal Instincts

Are ImpressiveI think maybe he means my plumage

does not distract from my talons.How in the requiem of my ovaries

I am building a barn full of pianos.Or perhaps my fears still wear

their oversized clothing?I don't know what he means.

Some people will eat anything.I wish I dreamed of wild horses

instead of hamsters.When Persephone fell down

off the bathroom counterI tried all night to bring her back.

She had six babies to feed,each smaller than my pinky.

So even after her sister Lunachewed off half her face, I let

those blind squirming erasers sucktheir dead mother until I had to

pluck them off one by one by one.--- Jenny Browne © 2015

The Boston Review

Dumpsters

Patti WhiteI met her in the Public Library, reading Sir Thomas Wyatt,

the Elder, the Renaissance court poet you know, you know the one

about the deer, they flee from me, like how tourists scurry away

only in the poem it's the beggars, the lovers, the deer

who run after having fed, the deer refuse to return to his hand,

it's a sad story.An educated woman, and a clean one: she bathes in the restroom

on the third floor; when she begs on 42nd Street she's a queen,

a rock in the current, impeccable, correct, her open palm

smooth and dry as a hen's egg. Her knitted cap covers hair

I've combed out with my own fingers. She comes to meafter rush hour, and we walk like in the movies, down alleys;

she recites poetry, she wears moonlight and neon like a crown,

and we eat whenever we please. Sometimes I find an empty dumpster,

not one near a restaurant but a business dumpster, one that held

shredded printouts, canceled checks and memos, fax paper, forms,

and we climb inside, concealed, sheltered, and make love. Oncewhen she was angry, she crawled out of the dumpster and beat

on the metal with an abandoned chair she found outside, thunder

whispers in comparison; it was the sound of absolute hell, utter

destruction; my head hurt for a week. I know I'm not the manof her dreams. I'm King Lear on the heath, crazy, cold with

despair; I rave; my clothes are shabby. With my kingdom

divided, there are no more decisions to make, and my mind

gets weak. She is a scholar; I am afraid of books. I rave

and she listens to me, comforts me, tells me my daughter

will save me one day and I believe her.--- From Tackle Box

©2002 Ashinga PressGood GirlLook at you, sitting there being good.

After two years you're still dying for a cigarette.

And not drinking on weekdays, who thought that one up?

Don't you want to run to the corner right now

for a fifth of vodka and have it with cranberry juice

and a nice lemon slice, wouldn't the backyard

that you're so sick of staring out into

look better then, the tidy yard your landlord tends

day and night --- the fence with its fresh coat of paint,

the ash-free barbeque, the patio swept clean of small twigs ---

don't you want to mess it all up, to roll around

like a dog in his flowerbeds? Aren't you a dog anyway,

always groveling for love and begging to be petted?

You ought to get into the garbage and lick the insides

of the can, the greasy wrappers, the picked-over bones,

you ought to drive your snout into the coffee grounds.

Ah, coffee! Why not gulp some down with four cigarettes

and then blast naked into the streets, and leap on the first

beautiful man you find? The words Ruin me, haven't they

been jailed in your throat for forty years, isn't it time

you set them loose in slutty dresses and torn fishnets

to totter around in five-inch heels and slutty mascara?

Sure it's time. You've rolled over long enough.

Forty, forty-one. At the end of all this

there's one lousy biscuit, and it tastes like dirt.

So get going. Listen: they're howling for you now:

up and down the block your neighbors' dogs

burst into frenzied barking and won't shut up.--- ©2011 Kim Addonizio

In Our StairwellIn the evenings,

a bunch of youths

dwelt in our stairwell.

They drank vodka,

pissed up the wall

and jeered humankind.

Every morning, as I went to work,

there was an empty bottle

on a landing,

and it smelt of urine.Once I said to the youngsters,

"You may drink vodka if you wish,

but it would be better if you

refrained from urinating here,

it's not a nice thing to do.

As for humankind,

we should not laugh at it

but mourn it."Since that day

the youths in our stairwell

drink vodka,

lament bitterly over humankind

and exhaust themselves

abstaining from urination.

They would rather die than take a piss.- - - Gennady Alexeyev

Translation ©1987 Anatoly Kudryavitsky

From A Night in the Nabokov HotelDeath(having lost)death(having lost)put on his universe

and yawned:it looks like rain

(they've played for timelessness

with chips of when)

that's yours;i guess

you'll have to loan me pain

to take the hearse,

see you again.Love(having found)wound up such pretty toys

as themselves could not know:

the earth tinily whirls;

while daisies grow

(and boys and girls

have whispered thus and so)

and girls with boys

to bed will go,--- From 50 Poems

E. E. Cummings

Isabel's Corrido

Para IsabelFrancisca said: Marry my sister so she can stay in the country.

I had nothing else to do. I was twenty-three and always cold, skidding

in cigarette-coupon boots from lamppost to lamppost through January

in Wisconsin. Francisca and lsabel washed bedsheels at the hotel,

sweating in the humidity of the laundry room, conspiring in Spanish.I met her the next day. Isabel was nineteen, from a village where the elders

spoke the language of the Aztecs. She would smile whenever the ice pellets

of English clattered around her head. When the justice of the peace said

You may kiss the bride, our lips brushed for the first and only time.

The borrowed ring was too small, jammed into my knuckle.

There were snapshots of the wedding and champagne in plastic cups.Francisca said: The snapshots will be proof for Immigration.

We heard rumors of the interview: they would ask me the color

of her underwear. They would ask her who rode on top.

We invented answers and rehearsed our lines. We flipped through

Immigration forms at the kitchen table the way other couples

shuffled cards for gin rummy. After every hand, l'd deal again.Isabel would say: Quiero ver las fotos. She wanted to see the pictures

of a wedding that happened but did not happen, her face inexplicably

happy, me hoisting a green bottle, dizzy after half a cup of champagne.Francisco said: She can sing corridos, songs of love and revolution

from the land of Zapata. All night Isabel sang corridos in a barroom

where no one understood a word. I was the bouncer and her husband,

so I hushed the squabbling drunks, who blinked like tortoises in the sun.Her boyfriend and his beer cans never understood why she married me.

Once he kicked the front door down, and the blast shook the house

as if a hand grenade detonated in the hallway. When the cops arrived,

I was the translator, watching the sergeant watching her, the inscrutable

squaw from every Western he had ever seen, bare feet and long black hair.We lived behind a broken door. We lived in a city hidden from the city.

When her headaches began, no one called a doctor. When she disappeared for days, no one called the police. When we rehearsed the questions

for Immigration. Isabel would squint and smile. Quiero ver las fotos.

she would say. When the interview was canceled, like a play on opening night

shut down when the actors are too drunk to take the stage. After she left,

I found her crayon drawing of a bluebird tacked to the bedroom wall.I left too and did not think of Isabel until the night Francisca called to say:

Your wife is dead. Something was growing in her brain. I imagined my wife

who was not my wife, who never slept beside me, sleeping in the ground,

Wondered if my name was carved into the cross above her hand, no epitaph

and no corrido, another ghost in a riot of ghosts evaporating from the skin

of dead Mexicans who staggered for days without water through the desert.Thirty years ago, a girl from the land of Zapata kissed me once

on the lips and died with my name nailed to hers like a broken door.

I kept a snapshot of the wedding: yesterday it washed ashore on my desk.There was a conspiracy to commit a crime. This is my confession: I'd do it again.

--- From Poetry of Resistance

Martín Espada

©2016 University of Arizona PressMen as Trees, WalkingI learned early what that verse

meant, "For now we see as through a glass

darkly." My mother wouldn't buy me any

glasses because then I'd be a foureyes

maybe even play in the band like the rest

of the pansies, or like my father, polishing

his lenses, head bent, hands

before his face as if

praying, no football

hero. Teachers tired of my leaning

in from the front row, chalk dust in

my hair, begged her in notes: like the blind

man in the Bible miracle, he sees men

as trees, and trees as lime

jello. Going out for passes, I was

lost like the end of the world when

everybody running sees the sky but me.

The coach threw his hat in the dust, "Son,

have you EVER caught a pass?" I never

did, but when she gave in, let me have

my specs, it was like heaven, she even more

beautiful with wrinkles, people gross

as bears now limber as hickory, spare

as willows. And the trees, firmed up,

erect at last, were like emerald fish

with each scale whole and succinct,

as if they would never, ever drop a leaf

or a pass.--- William GreenwayTalking Big

John Bricuth We are sitting here at dinner talking big.

We are sitting here at dinner talking big.

I am between the two dullest men in the world

Across from the fattest woman I ever met.

We are talking big. Someone has just remarked

That energy equals the speed of light squared.

We nod, feeling that that is "pretty nearly correct."

I remark that the square on the hypotenuse can more

Than equal the squares on the two sides. The squares

On the two sides object. The hypotenuse over the way

Is gobbling the grits. We are talking big. The door

Opens suddenly revealing a vista that stretches

To infinity. Parenthetically, someone remarks

That a body always displaces its own weight.

I note at the end of the gallery stands a man

In a bowler and a black coat with an apple where

His head should be, with his back to me, and it is me.

I clear my throat and re (parenthetically) mark

That a body always falls of its own weight.

"whoosh-WHOOM!" Sighs the hypotenuse across,

And (godknows) she means it with all her heart.--- From Words Burnished by Music

©2004, Johns Hopkins

University Press

When I Was a Tiger

Translated by Lisa RappoportWhen I was a tiger

I hunted in the forestMy claws struck me as quite beautiful

when I tore into gazelles with themAt night I dreamt of red flesh, white teeth,

my lover's ebony eyesDuring the day I wandered, hunted, and listened

for a signal from my heartThe whole world was striped

like meCuando era tigre

[Lisa Rappoport y Sasha Ryerson]Cuando era tigre

cazaba en la selvaJuzgaba mis garras muy hermosas

cuando las usaba para atacar las gacelasLas noches soñaba en carne roja, dientes blancos,

los ojos negros de mi amorLos días caminaba, cazaba y esperaba

un señal de mi corazónTodo el mundo era rayado

como yo

RelaxBad things are going to happen.

Your tomatoes will grow a fungus

and your cat will get run over.

Someone will leave the bag with the ice cream

melting in the car and throw

your blue cashmere sweater in the dryer.

Your husband will sleep

with a girl your daughter's age, her breasts spilling

out of her blouse. Or your wife

will remember she's a lesbian

and leave you for the woman next door. The other cat ---

the one you never really liked --- will contract a disease

that requires you to pry open its feverish mouth

every four hours. Your parents will die.

No matter how many vitamins you take,

how much Pilates, you'll lose your keys,

your hair, and your memory. If your daughter

doesn't plug her heart

into every live socket she passes,

you'll come home to find your son has emptied

the refrigerator, dragged it to the curb,

and called the used --- appliance store for a pickup --- drug money.

The Buddha tells a story of a woman chased by a tiger.

When she comes to a cliff she sees a sturdy vine

and climbs halfway down. But there's also a tiger below.

And two mice --- one white, one black --- scurry out

and begin to gnaw at the Vine. At this point

she notices a wild strawberry growing from a crevice.

She looks up, down, at the mice.

Then she eats the strawberry.

So here's the view, the breeze, the pulse

in your throat. Your wallet will be stolen, you'll get fat,

slip on the bathroom tiles in a foreign hotel

and crack your hip. You'll be lonely.

Oh, taste how sweet and tart

the red juice is, how the tiny seeds

crunch between your teeth.--- From Like a Beggar

Ellen Bass

©2014 Copper Canyon Press

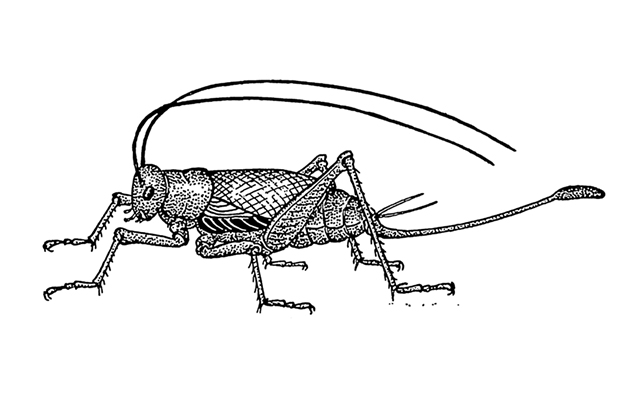

Sonnet for My Backyard Crickets,

Two Weeks GoneWell, crickets, you're gone again

and again I haven't gotten around

to thanking you properly - - - a habit of mine.

The same thing happened with my ex-husband,

though, at least, in his case, I tried.

(He hung up on me. Soon after, he died

but that's an old story. And long.)

My plan had been to pay my debt in song,

one from me for a thousand or two from you,

each a precisely calibrated hybrid

of lamentation and nightly lullaby.

From the sound of things, it was pretty hard,

whatever let you know just where you'd find me.

I'm so sorry, crickets. I'll miss you. Thank you.--- Jacqueline Osherow

© 2016 Antioch Review

Olives"Dead people don't like olives,"

I told my partners in eighth grade

dancing class, who never listened

as we fox-trotted, one-two, one-two.The dead people I often consulted

nodded their skulls in unison

while I flung my black velvet cape

over my shoulders and glowered

from deep-set, burning eyes,walking the city streets, alone at fifteen,

crazy for cheerleaders and poems.At Hamden High football games, girls

in short pleated skirts

pranced and kicked, and I longed

for their memorable thighs.

They were friendly --- poets were mascots ---

but never listened when I told them

that dead people didn't like olives.Instead the poet, wearing his cape,

continued to prowl in solitude

intoning inscrutable stanzas

as halfbacks and tackles

made out, Friday nights after football,

on sofas in dark-walled rec rooms

with magnanimous cheerleaders.But, decades later, when the dead

have stopped blathering

about olives, obese halfbacks wheeze

upstairs to sleep beside cheerleaders

waiting for hip replacements,

while a lascivious, doddering poet,

his burning eyes deep-set

in wrinkles, cavorts with their daughters.--- Donald Hall

©2006 Poetry MagazineBean Soup

Or a Legume MiscellanyNobody there is that doesn't love a bean.

If not the royal Navy bean, then the wax bean,

the soybean, the green bean, the black bean -- the

pot is large, it contains multitudes -- white bean,

pink bean, small red bean, the lowly pinto, the

lovely lentil -- let the lamp affix its bean -- or

the walnut-shaped garbanzo, large lima bean, baby lima,

(A reunion of the Bean families is here assembled),

the cranberry bean, white kidney bean, northern bean,

or their cracked cousins: green split pea, yellow

split pea, and ol' blackeye. A lineup

of likely legumes. Gather ye bean-pods

while ye may. Go and catch a falling bean

and if you catch one, let me know.

A man and a woman are one. A man and a woman

and a bean are one, or two, or three.The beans I mean, no one has seen them made

or heard them made, but at supper-time

we find them there. Come live with me,

and eat some beans and we will love

within our means. One could do worse

than be an eater of beans.Shall I compare thee to a summer's bean?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate.

Had we but world enough, and time,

this coyness, Lady, were no crime.

But, at my back, I always hear

a pot of beans bubbling near.Mark but this bean, and mark in this,

how little that which thou deny'st me is.

An aged bean is but a paltry thing.

I must lie down where all ladders start,

in the foul rag-and-bean shop of the heart.

O my love is like a red, red bean,

that's newly picked in June:

O my love is like a pinto bean,

that's truly cooked at noon.So much depends upon a red kidney

bean. You might ask, Do I dare

to eat a bean? Dry beans can harm no one.

They remind us of home sweet home,

home on the range,

home where the heart is.

Without expecting anything in return,

they give us protein, zip, and gas.

Add what you will -- onion, tomatoes, red

pepper, chili powder, juice of lemon,

salt & pepper to taste. Add ham

hocks, bring to a boil, simmer slowly.

Call your friends, serve with

panache, crackers, and green salad.How do I cook them? Let me count the ways --

boiling, steaming, frying, baking.

And if these verses may thee move,

Sweet Lady, come live with me

and be my love. And if this fare

you disapprove, come live with me

and please be my cook.