Heavy Metal

A Novel Andrew Bourelle

(Autumn House)

I scarcely thought I would ever be sharing, much less reviewing a book with folk like Iron Maiden, AC/DC, Anthrax, Sabbath, Slayer, Def Leppard, Megadeath, or my favor despite it all, the Dropkick Murphys.I suspect that the masters of Heavy Metal - - - if this is not an oxymoron - - - expect that the life and times of AC/DC should to be worth reading, much less appearing in any novel of my choice.

But - - - this is ridiculous, I am, as Walt Kelly would say, replete with rue. Yet this one I could not put down which may suggest my own angst in juvenilia: that it is possible to pick any subject, with any character, much less characters like we have here, and somehow build a good story.

We begin with Craig's mother killing herself, which, in this case, is appropriately grisly (gun, mouth). And, then, with the self-same gun in his hand, Craig - - - around fifteen, with all the baggage that implies - - - is debating following her down her bloody path. (This recalls a recent study that pointed out that American juveniles, between the ages of 13 to 18, when tied down and given brain scans, show many of the characteristics of patients with a heavy dose of schizophrenia.

Craig, in Heavy Metal, is a perfect example. When he is with anyone except his older brother or Betsy his heart-throb when they are together, does barely manage to croak out a few full sentences; but with others - - - parents, friends, police, school counsellors, any adult - - - he does the very thing that renders parents and the rest of us blazingly mad. With his father, the old man in his dirty clothes from his work at the factory, Craig doesn't just shut up, he doesn't answer, doesn't respond; sulks.

The high point of Heavy Metal is our gang getting stoned, listening to some noise lovingly recorded by Metallica, named "One." [Pardon the lack of dialogue quotes here and below. This may be the author's conscious tribute to early Joycean minimilism, or it might be just a case of better safe than sorry, just like the usual operating system of our juveniles.]

They never say the word "One" in the whole song?

Yeah, they do, Luke says. There's that part where he says he's a one.

Doug coughs smoke and says, He's a one.

That doesn't make any sense.

Yeah, Kenny says. What's that supposed to mean?

I don't know, Luke says. But I looked at the lyrics and that's what it says.

Bullshit, Doug says. I don't believe it.

Then you tell me why the song is called "One."

Luke repacks the bowl. The song is playing.

[Craig:] I think about not speaking up, but I do.

What this all is supposed to mean is that, well, here's song is about a guy who's lost his arms and legs, and he can't see or hear or smell or any of those things. He's completely cut off from the world. The world is gone. He's in darkness. Nothing but his own consciousness. When he says he's just one, he means alone.

§ § § Does all this mean I'm going to have to start listening to Metallica? Possibly. But better, we find it an elegant reflection of Craig's interaction with the world. Mother dead; Craig not all that intimate with his friends; brother run off, possibly with stolen money; father in front of the tv every evening with his cans of beer, cigarettes, and his deep suspicion of his two sons.

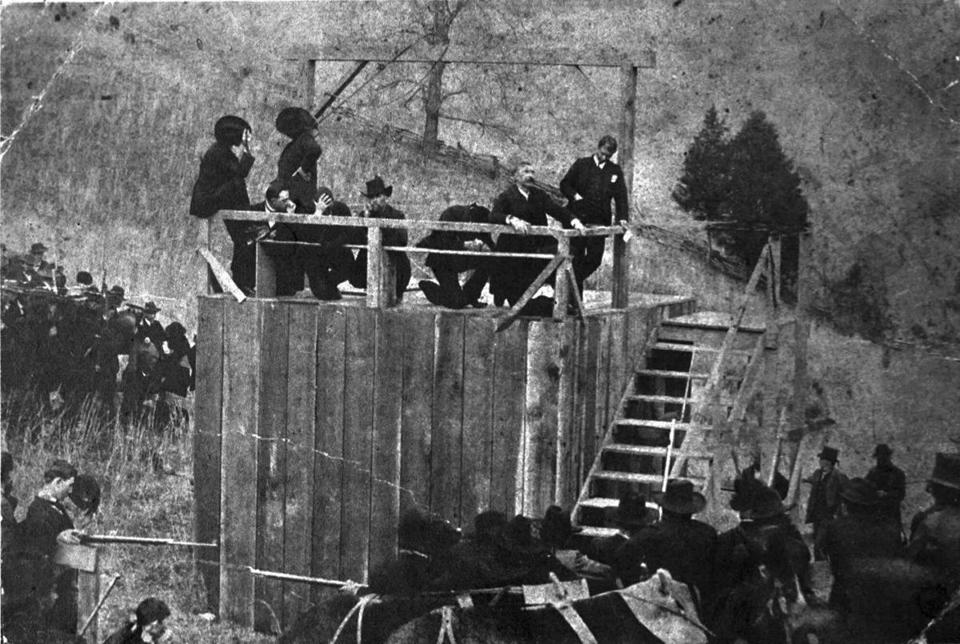

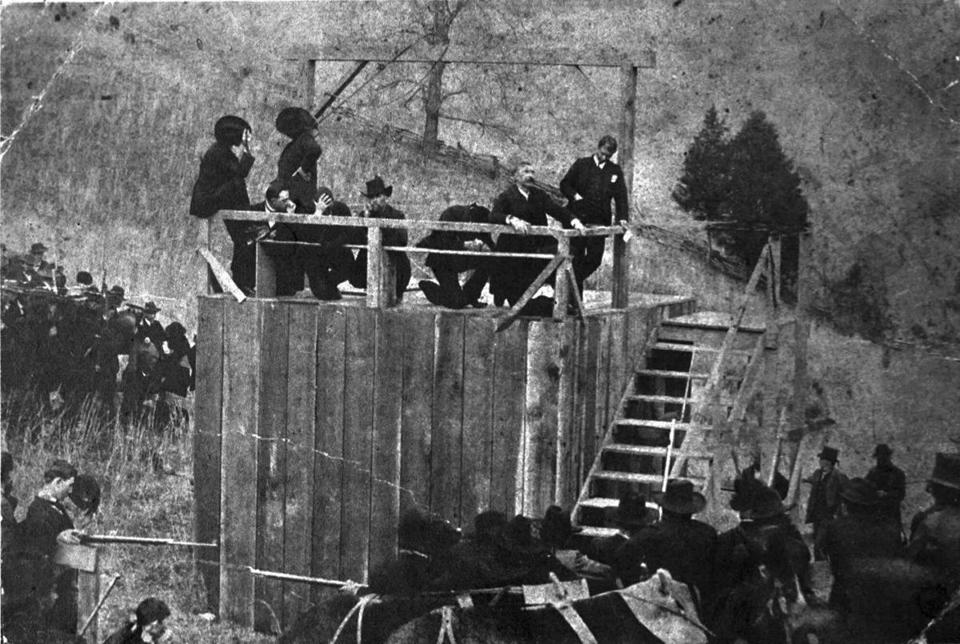

It's also a nice tribute to Dalton Trumbo.

§ § § The following takes place in the local junk yard:

Some of these cars carry the weight of death. Teenagers compacted behind steering wheels, trapped in burning cars. Toddlers thrown through windshields. Pedestrians struck, their bones shattered, their muscles pulverized. Metal stretches in every direction, a labyrinth of rusting, twisted machines smelling faintly of burnt oil.

From its first moment, the gun plays a starring role in Heavy Metal; indeed, it is one of the heaviest of metals. Craig is constantly playing with it, wondering what it would mean to shoot himself, or, later, shoot others, those of his peers who beaten him, have insulted him. One of the heaviest passages has him in fantasy appearing in the high school cafeteria with a .38, spraying Jamie with bullets.

Jamie is such a jerk that we readers, don't ask me how, find ourselves cheering Craig on. It becomes an action/shot tragedy, pure Aristotelean catharsis that would be for all of us, a simple deathly joy. Thus when Jamie goes after Criag out in the junkyard with his two heavies and a tire iron, we can hardly wait to see the bastard get his.

Finally, and best, author Bourelle is not without a touch of wit. This is his dialogue in the halls of school, with Gretchen, the vamp who started this McCoy-mountain feud between Craig and Jamie. Gretchen is trying to get Craig an excuse for being late:

Mrs. O'Rourke, who is young and plump and friendly, thinks about this for a moment . . . and then Gretchen's magic takes its effect. Her face changes and, although she doesn't say anything, it's clear that she's going to accept this explanation. She turns to me.

And you? she says.

Oh, he was just heading to the office, Gretchen says. Don't worry, she says to me, putting her hand on my shoulder. I don't think they'll count you tardy. Diarrhea is a valid excuse.

Mrs. O'Rourke looks back and forth between us, red blooming on her cheeks like a rose.

I put my hand on Gretchen's shoulder. And you shouldn't worry, I say. I'm sure Mrs. O'Rourke can help you find a book on teenage pregnancy.

Gretchen flinches.

Before she can say anything else, I turn and walk down the hallway.