The Man in the High Castle

Philip K. Dick

As read by Jeff Cummings

(Brilliance Audio)

When I read The Man in the High Castle twenty-five years ago, I recall being baffled by the story's "cosmological text," and the constant references to the I Ching with its divination system, the throwing of the coins or the yarrow sticks, the "hexograms." But I was easily sucked in by Philip Dick's alternate history.His conceit works like this: at the end of WWII, the two victors jointly occupied the United States. Germany took over the East Coast, Japan took West, leaving a neutral zone in the Mountain states.

The author cleverly fiddles with the facts as we think we know them to create an outcome that could well have been ours had we been passing through an alternative time warp. Here, Franklin Roosevelt is assassinated in Miami, in 1933 --- a bit of history culled from historical fact. As the president-to-be was returning from a fishing trip with various moguls, at the back of the crowd one Giuseppe Zangara takes out his pistol, aims and fires.

Now since Zangara was only five feet tall, totally bonkers, and, on top of that, a lousy shot --- with the crowd in his line of vision, he managed to kill and wound five other people, but missed FDR completely. The NRA should sign him up as a Poster Boy.

Zangara turns out to be a regular character that could have been created by an author like Dick. For instance, he was sentenced to the electric chair --- not for having missed Roosevelt, but for having, in his misbegotten attempt, killed the mayor of Chicago, Anton Cermak. He showed no remorse, was evidently delighted by the turn of events, and at his hearing, shouted at the judge, "You give me electric chair. I no afraid of that chair! You one of capitalists. You is crook man too. Put me in electric chair. I no care!"

But the death of Roosevelt in The High Castle leads to two terms by Vice-President elect "Cactus Jack" Garner. [See Fig. 1 above. He's the one with the bad cigar and the sour face.] This was a man who had claimed. loudly, that being Vice-President was not worth "a bucket of warm piss." He also comes close to being another character that Dick may well have invented.

As leader of the House of Representatives, Garner and his cronies would meet in what he called the "board of education" --- a gathering for his lawmaker friends to gossip and tell dirty jokes and drink whiskey and branch-water. Or as Garner dubbed it, "strike a blow for liberty." (This was during the era of Prohibition.)

Photographs of Garner show him looking strangled by his required white-collar shirt and tie. He bemused reporters with his crude language and even cruder ideas of America.

His sense of political power was scenic and funny (he was intellectual godfather to another, not-so laid-back, certainly not so funny Texas high country cracker, George W. Bush).

Time Magazine wrote in 1936,

Cactus Jack is 71, sound in wind & limb, a hickory conservative who does not represent the Old South of magnolias, hoopskirts, pillared verandas, but the New South: moneymaking, industrial, hardboiled, still expanding too rapidly to brood over social problems. He stands for oil derricks, sheriffs who use airplanes, prairie skyscrapers, mechanized farms, $100 Stetson hats.

He was even less beloved of labor leaders. John L. Lewis, the acerbic head of the United Mine workers, described him as "a labor-baiting, poker-playing, whiskey-drinking, evil old man." He was what we in the south would call a "cracker;" one who, like Huey Long, would delight newsmen like H. L. Mencken, Westbrook Pegler, and Ring Lardner.

He was profane, and crass, and decidedly idiosyncratic. In 1895, Mariette Rheiner had run against him in a local race for County Judge of Uvalde County. She lost by a few votes, so he married her.

We can imagine, if Garner had fallen thus into the presidency of the U. S. in 1933, he would have handled favoritism (and the complex national and international traps of the 1930s) as astutely as did Warren G. Harding.

And as an old isolationist who could see no further than the nearest oil well, he would have been completely outmaneuvered by Hitler, would have ignored the Civil War in Spain, would have been baffled by the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, would never have created Lend-Lease, never would have seen the Fall of France for what it was (a disaster that might well have led to the invasion of England).

This is rich. I start out to review The Man in the High Castle, and end up dwelling on Giuseppe Zangara and John Nance Garner. It's just as well. I'm having trouble with Philip Dick's novel, even though it won high praise when it came out in 1962. You might just want to skip the stuff I've stuck in below: go on to another of review in this issue of the magazine, like the one on H. L. Mencken, which gives real examples of a real book reviewer, not some spurious amateur. Because when I don't get a book at all, I tend to ramble, take the mountain road instead of the freeway, regularly get lost and then run into the dead ends, in this case, in this book, the very mysterious final pages.

As I say, I had read The Man in the High Castle years ago . . . found it vaguely incomprehensible. But the fantasy-facts reconstructed by the author are all brilliantly deployed, woven into the text: The death of Roosevelt. The elevation of Garner. The fall of Russia to the Nazis in 1941 (the Soviets being plagued and ultimately defeated by lack of material support from isolationist America).

And then there was the complete destruction of the American Naval Fleet in 1941 at Pearl Harbor; the invasion and fall of England (once again, because of lack of matériel support from the United States). This leads to the defeat of the United States, the victory of the Japanese and Germans in 1947, the subsequent take-over of Africa by the Nazis (with its ethnic cleansing which leaves few survivors). Finally there is the filling in of the entire Mediterranean Sea with rich earth to create a plentiful source of foodstuffs for Nazi Europe, after which the Germans, under Willie Ley, proceeded to set up colonies on the moon and various planets.

With the take-over of the Western United States by the Japanese, we see a gradual enculturating of Americans. We begin to turn Japanese. We find some characters, like the American antique dealer R. Childan smoking "Land-O-Smiles" marijuana cigarettes, selling memorabilia of the old United States: butter churns, WPA posters, Victrolas, and Mickey Mouse watches. He, and most of the others here, regularly consult the I Ching, "the Book of Changes."

Americans begin to show shape-shifting character traits, copying what we used to think of as "Oriental Calm." Major decisions are dictated by the I-Ching; for Americans in the West, we see the rise of the Stockholm Syndrome in spades.

When Childen visits a rich, sophisticated couple just over from Tokyo, he enters their apartment, bowing, and thinks

Tasteful in the extreme. And --- so ascetic. Few pieces. A lamp here, table, bookcase, print on the wall. The incredible Japanese sense of wabi. It could not be thought in English. The ability to find in simple objects a beauty beyond that of the elaborate or ornate. Something to do with the arrangement.

Another character, Frank Frink, wants to set up a jewelry business. He consults the oracle, throws the yarrow sticks and thinks,

Here came the hexagram, brought forth by the passive chance workings of the vegetable stalks. Random, and yet rooted in the moment in which he lived, in which his life was bound up with all other lives and particles in the universe. The necessary hexagram picturing in its pattern of broken and unbroken lines the situation.

Later, he and a friend make the jewelry, and carry it to Childen's store. He agrees to take the pieces on consignment. We get to listen in on Frink's thinking, one that begins more and more to sound Oriental: the omission of the indefinite articles and pronouns, stand-alone verbs, all coming from imitating the English spoken by the new conquerers of San Francisco:

The Moment changes. One must be ready to change with it. Or otherwise left high and dry. Adapt.

The rule of survival, he thought. Keep eye peeled regarding situation around you. Learn its demands. And --- meet them. Be there at the right time doing the right thing.

Be yinnish. The Oriental knows. The smart black yinnish eye.

The "yinnish" eye.

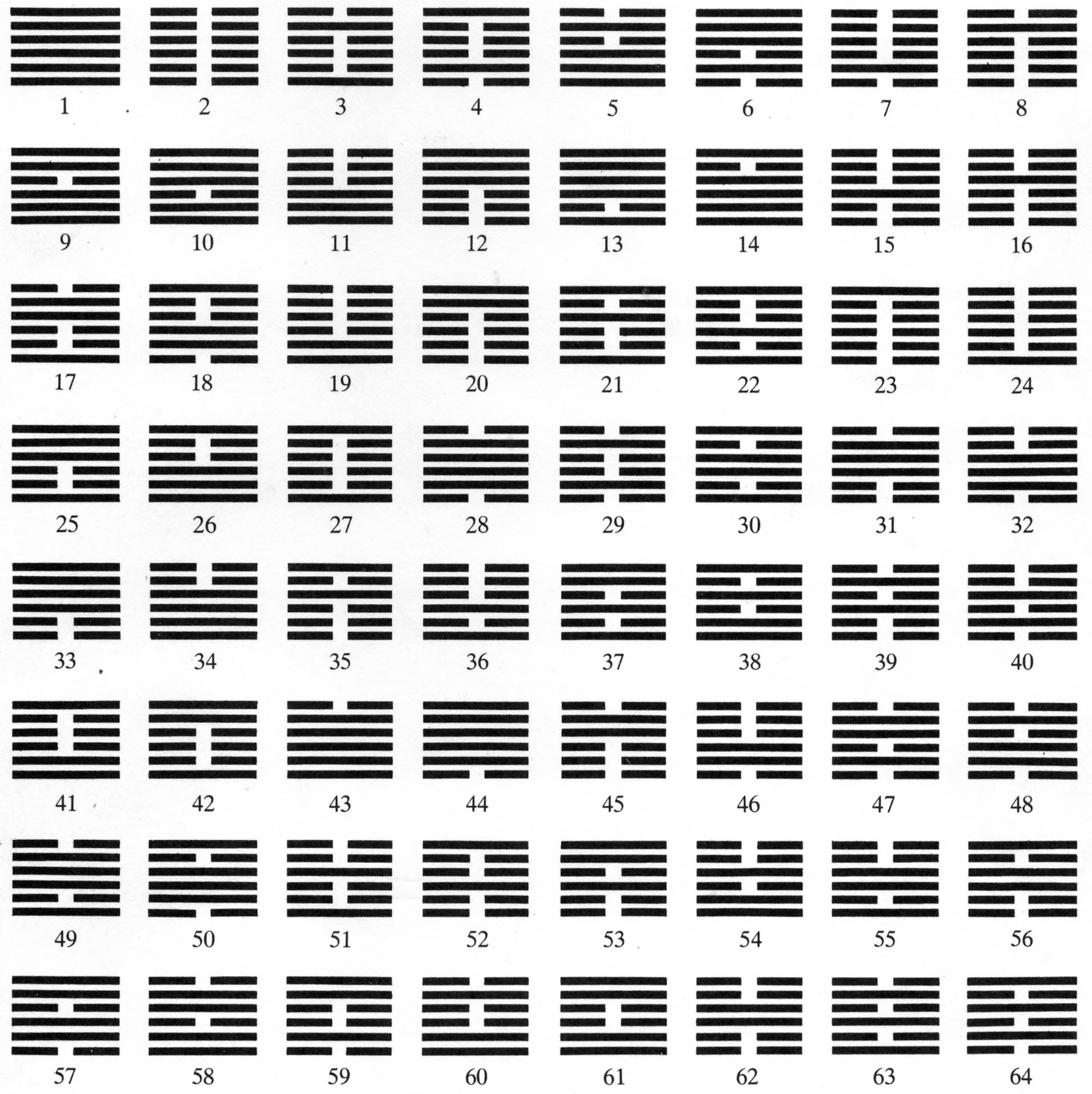

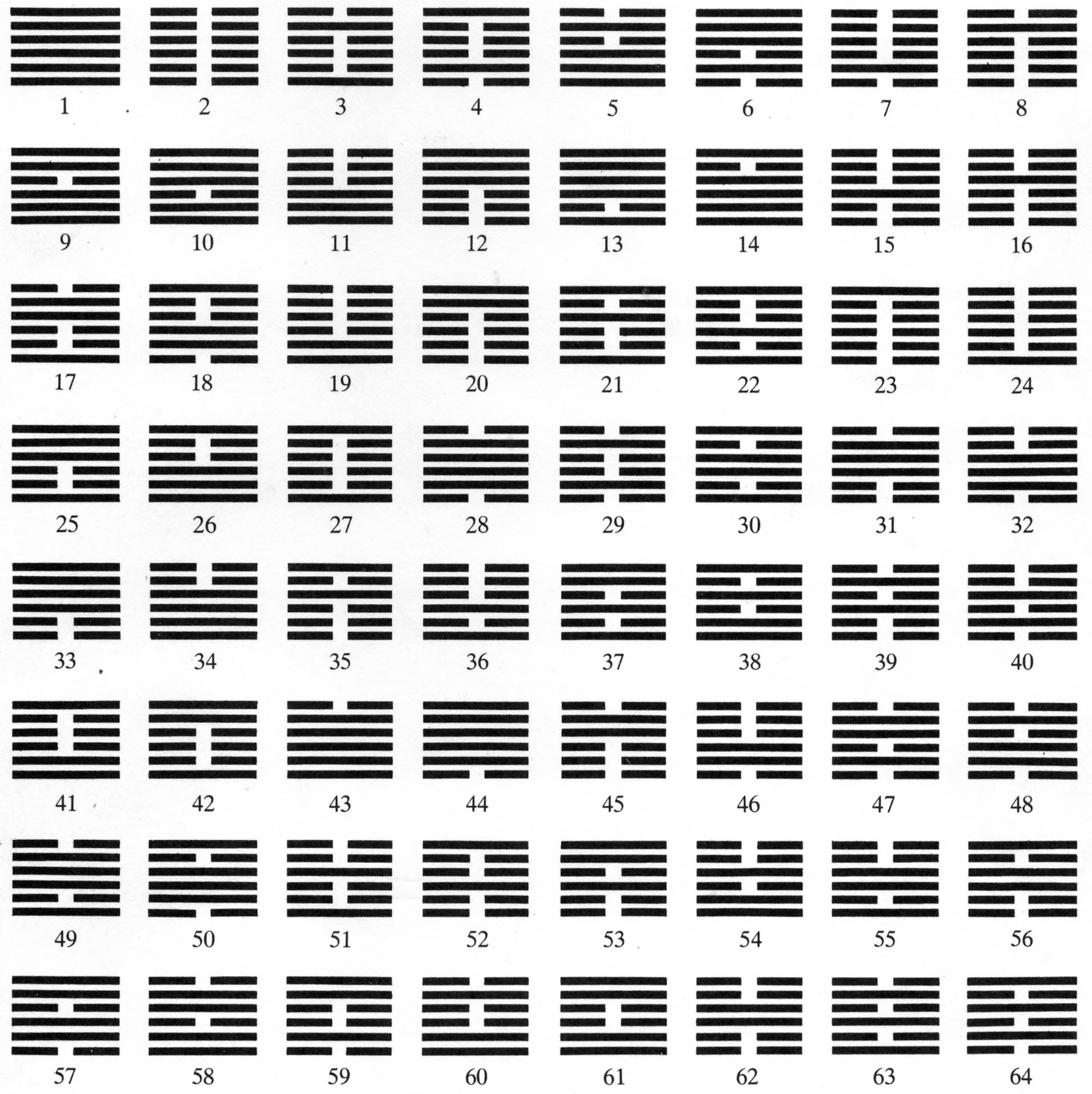

§ § § It is said that Dick wrote this novel with continuing help from the Book of Changes. When deciding what might happen next, he threw the stalks, culled the sixty-four hexagrams, and from the vague (maddeningly vague) language from 2,600 years ago, decided the next twist of plot. All of the characters in The Man in the High Castle do exactly the same when they are faced with a crucial decision. Frink wants to know if he should set up the jewelry business, and begins by writing out his question on a piece of paper, as one is encouraged to do. The result: "Yin. A six. It was Peace . . . Opening the book, he read the judgment."

PEACE. The small departs.

The great approaches.

Good fortune. Success.Ah, says Frink. Great. I should do it. But then: there is the matter of "the moving lines." (I told you it was complicated. As well as baffling. Contradictory. Confusing. Sometimes hopelessly so.) "His eyes picked out the line, read it in a flash."

The wall falls back into the moat.

Use no army now.

Make your commands known within your own town.

Perseverance brings humiliation."My busted back! he exclaimed, horrified."

The Book of Changes turns out to be yet another character in The Man in the High Castle. A puzzling one too. Dick explains in his brief "Acknowledgments," "The version of the I Ching or Book of Changes used and quoted in this novel is the Richard Wilhelm translation rendered into English by Cary F. Baynes, published by Pantheon Books, Bollingen Series XIX, 1950 by the Bollingen Foundation, Inc., New York."

Later scholars have found that the Wilhelm version of the I Ching, originally translated from Early Old Chinese into German, and from that into English, is defective, with language and suppositions that badly distort the original. Thus we find in The Man in the High Castle an exotic divination that, because of faulty language, misses the intent if not the spirit of the original. It is thus a historic story that starts and ends by missing the boat.

This lack of clarity, the muddy story line, the defective mystical insights: all seems to delight the many fans of Philip K. Dick. Despite the fact that it is reeking of confusion and a basic misapprehension, we come to love it as if these imperfections give it a special illogical perfection.

To check our observations, we went directly to the I Ching --- pronounced "ee jing" --- online. One can do this now without even touching a yarrow stalk or the obligatory three Chinese coins with a square hole in the middle, tied together by a red silk ribbon.

No matter how I did it, I figured it would, with its skewed but elegant grace, give us an honest evaluation of this review.

We tossed our electronic sticks and came up with "Hexagram 23 . . . named "Stripping." Other variations include "splitting apart" and "flaying."

Got it? "Stripping." "Splitting apart." "Flaying."