Jack London

The Paths Men Take

Photographs, Journals and Reportages

David Sapienza, Editor

(Contrasto)

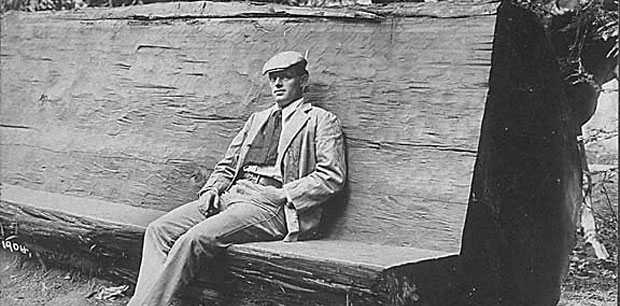

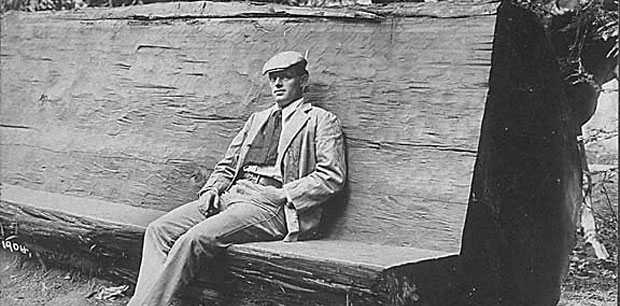

He probably cared too much. Whether it was agonizing over the poor of East End London, or the rapidly dying indigenous peoples of the islands of the South Pacific, or the soldiers on either side in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904 - 1905 - - - his call was the care for all humanity, especially those who were caught up in the toils of the great powers. And at a time when it was ill-advised to do so, he called himself "socialist." For him, just having a political tag was no big deal. Perhaps it was just another disguise.He had been born John Griffith Chaney in 1876, made himself famous by creating such readable volumes as The Call of the Wild and White Fang, the latter being that refreshingly chilly novel that caught me so long ago: a man pitted against a cold so anguishing that it often invited one (I still remember this) to stop battling it, to lie down in the snow-bank, let yourself be lulled in by the cold, so that the warm only existed, in the depths of the heart of you; and if you let it, the chill would turn into a point of warmth as sleep carried you and your life off, with a minimum of foo-foo-raw.

This volume is the briefest story of his life, one who by age eighteen had already "been a seafarer, an oyster pirate, and young cabin boy in Japan hunting for seals for seven months." With tales of the bitterly cold ice fields of the Arctic and the bitterly poor of London (The People of the Abyss) he had created a body of writing that would come to astonishing fruition in the final sixteen years of life.

He died in 1916, just forty years old, having lived what he wrote . . . but more astonishingly, in the last years, producing some twelve thousand photographs, shot and developed on his own with his precious camera, one which was to cause so much bureaucratic dickering with the Japanese while covering their war for the American press.

The Japanese accused him of spying, taking pictures that were not to be taken, you are not allowed to show the truth of war; and he was only able to finally get himself bailed out by charming the other war reporters - - - he could be charming beyond all reason - - - to let him go on his own way beyond Chempulpo, off to the Battle at Yalu River and thence on to Antung, the battles of 1904 . . . and always with an eye for those who had been made homeless and hungry by these vicious wars between the great powers.

He survived, as always, in disguise. When he went into the barrios of the poverty-stricken in London, he disposed of his fancy duds (he was a careful dresser) and assumed the guise of the poorest of the poor.

No sooner was I out on the streets than I was impressed by the difference in status effected by my clothes. All servility vanished from the demeanour of the common people with whom I came in contact. Presto! in the twinkling of an eye, so to say, I had become one of them. My frayed and out-at-elbows jacket was the badge and advertisement of my class, which was their class. It made me of like kind, and in place of the fawning and too respectful attention I had hitherto received, I now shared with them a comradeship. The man in the corduroy and dirty neckerchief no longer addressed me as "sir" or "governor." It was "mate" now - - - and a fine and hearty word, with a tingle to it, and a warmth and gladness, which the other term does not possess. Governor! It smacks of mastery , and power, and high authority - - - the tribute of the man who is under to the man on top, delivered in the hope that he will let up a bit and ease his weight, which is another way of stating that it is an appeal for alms.

In disguise, London was always in disguise. And he is a writer, conscious that he is a man who uses words on paper, written alone, to be sent out to the world, this guy with the kind face is hidden. He is the one who puts out muckraking books like The Abyss, a man who could write

The first time I met with the English lower classes face to face, I knew them for what they were. When loungers and workmen, at street corners and in public houses, talked with me, they talked as one man to another, and they talked as natural men should talk, without the least idea of getting anything out of me for what they talked or the way they talked.

John Griffith Chaney in disguise, a man now named London in the heart of London, in disguise in the real London where the other Americans were "reduced to a chronic state of self-conscious sordidness by the hordes of cringing robbers who clutter his steps from dawn till dark, and deplete his pocket-book in a way that puts compound interest to the blush."

This book is lovely, and, too, is in disguise. We think we are going to get the secret of a secret man, the one who was so suicidal that he had to tell others to hide away his pistol from him. And for the fifty years after his death, it was rumored . . . and believed . . . that he had done himself in. This book has no answer for those questions, the question of the Real London. Rather, it is an artful, leisurely volume that takes him from his early successes into the making of The Abyss, and thence deep into his experience of one of the oddest wars of the new century - - - one in which one of the smallest countries on the planet (377,972 kilometres2) was able to conquer one of the most gargantuan on the planet (17,125,200 kilometres2).

§ § § And from thence to San Francisco, to the earthquake of 1906 - - - the one that struck at 5:12 a.m. on April 18 with an estimated moment magnitude of 7.8, killing 3,000, destroying 80% of the city. He there in the town of Glen Ellen, watching the smoke far to the south, where, he reported, he said to his wife, "I shouldn't wonder if San Francisco had sunk. That was some earthquake. We don't know but the Atlantic may be washing up at the feet of the Rocky Mountains." And as he and Charmian rode into the city, she was to write (she too was imbued with an authorial sensibility), about the face of a man, a stricken man in the street :

In my eyes, there abides the face of a stricken man, perhaps a fireman, whom we saw carried into a lofty doorway in Union Square. His back had been broken, as the stretcher bore him past, out of a handsome, ashen young face, the dreadful darkening eyes looked right into mine. All the world was crashing about him, and he, a broken thing, with death awaiting him inside the granite portals, gazed upon the last woman of his race that he was to ever see.

Finally, he, Jack London, with his charming Charmian, in his specially built ship, sailed into the part of the world which was, in turn, to finally deprive him of the life he lived so richly. They went directly into the area of the great islands of the great south seas:

Hawaii, the Marquesas, Tahiti, Samoa, the Fijis, the Solomon Islands, the Pacific markers that Jack London documented on his long and famous trip made on a home-built ship called the Snark, [showing] portraits infused with personality, exotic faces and stern eyes gazing through the lens - - - all infused with a universal dignity. They were published in 1911 and remain one of the best documents of this forgotten world.

These were, too, the very places with their random selection of tropical torments - - - uremia, the fevers, malaria, dengue, alcoholism, addiction to morphia - - - the maladies that were to divest this man of his supernatural strength, eating away at him until he was no more able to recover the power that drove him so hard, for so long, to the very ends of the earth.

--- Lolita Lark