The Huntress

The Adventures, Escapades, and

Triumphs of Alicia Patterson

Alice Arlen and Michael J. Arlen

(Pantheon)

Alicia Patterson defied the everyday picture of an entrepreneurial woman of pre-WWII America. Early in her career, despite her lofty connections in the media in Chicago - - - she abandoned the "Scott Fitzgeraldian ambience of country club, lawn tennis, polo - - - the whole pure high-WASP culture of the Midwest" - - - and ran off to be with her father in New York (Joe Patterson was owner of the highly successful Daily News).She was in no way flighty, but she did promptly join "a small, self-selected cohort of female pilots: aviatrixes, as they were called." She talked her father into the necessary monies for "flying suit, helmets, goggles, and so on, plus three hundred dollars . . . for a minimum of four months of lessons."

She survived the relatively dangerous early flights - - - it was 1929 - - - to go on for the necessary 200 hours of airtime which qualified her for a "transport pilot's license" . . . of which only nine American women had qualified for so far.

The permit allowed her to deliver mail, and instead of "making scenic runs up and down the Long Island seashore . . . she now had to plot a course for Cleveland or Detroit, hoping the weather would hold and her fuel remain sufficient, and get herself back by sundown."

On one such flight on a gray day she'd reached Detroit on schedule and made a turn for home, but then the weather closed in around her, and realizing she was lost, she brought her plane down low, flew above some railroad tracks for guidance until she found a farmer's field she could land in.

"When the weather lifted she got herself in the air again and made it back in time to Curtiss [airfield], where her instructor suggested she work a little harder on her navigation skills."

A reader would expect that this story of the life of Patterson would involve some further adventures scaring her family (and possibly herself) with aerial adventures - - - but no, this is primarily the story of how a rich and independent (and feisty) woman suddenly got herself deeply involved in the newspaper business. Fortunately for her, she had just decided to abandon her charming, flaky husband Joe Brooks who was, according to the authors of The Huntress one of those "larger than life characters beloved by many, certainly all those who didn't have to live with him."

When they finally parted, he wrote her, begging her to return: "Dear One, King Booj is missing Baby Booj unbelievably. Always fly fast and safe..."

Evidently, Baby Booj had problems with King Booj, perhaps even including being referred to as "Baby Booj." Fortunately, she had recently taken up with someone who did not saddle her with being his baby, but, instead, being one of the Guggenheims, one of the rich Guggenheims, one of the very rich Guggenheims - - - Harry Frank - - - he merely saddled her with her own newspaper.

A friend had taken her to Guggenheim's house, or, better said, his castle, "a facsimile of an entire thirteenth-century Normandy château" where she was introduced to him, "tall, handsome, gentlemanly, with piercing eyes, a friendly amused smile, older but not old."

She always remembered how Harry looked that night, and how he looked at her, and surely she at him.

It was Harry's friend, Max Annenberg, the newspaper magnate, always scouting for new properties, who discovered "not so much a newspaper as a defunct auto-dealership, in the small Long Island town of Hempstead . . . a little shopping sheet that had just ceased publication after only eight days in business . . ."

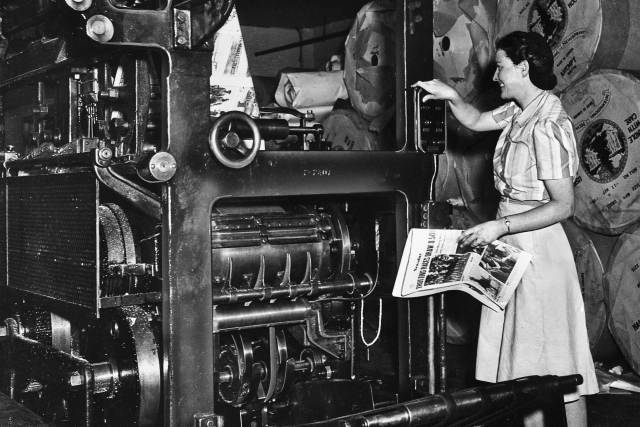

What she and Harry found were two presses that "were not only old but weren't at all suited to a tabloid format . . . "

that there was no space for a proper city room; that the setup seemed to limit them to a smaller-than-five-thousand print run; in other words, one of those then-fashionable, cute little country weeklies she wouldn't be caught dead publishing.

Perfect! Harry bought it, and Alicia started in on her path to becoming a newspaper publishing legend.

§ § § The advent of the highly successful Newsday - - - 450,000 circulation, Pulitzer Prize 1954 - - - is the major thrust of this book; how Alicia, with the help of - - - and later, over the dead body of, Harry - - - transformed this "Cute little country weekly" into one of the country's leading edge publications, with a formidable editorial voice.

Its rise came at just at the right moment for its locale. In the immediate post-WWII environment, Long Island was the center of the first of the great suburban building booms. And Newsday anticipated it in a series of prescient articles in 1943, and their dual fortunes were built in collusion with Levittown's creator, one Bill Levitt.

"During the war [he was] a builder of barracks for the navy, after war's end an ambitious visionary prophet of affordable mass housing, an industry that didn't yet exist."

His plan was to build simple, sturdy, wood-frame houses out of prefabricated modular components; then, with new techniques of pouring cement, fasten them to standardized cement-floor slabs, thus no basements but with all the new electric appliances.

"He could build them by the hundreds, by the thousands; in theory the more houses he built the cheaper they would be to construct and purchase."

Existing urban areas would never permit such housing, for it seemed "crass, lacking in the aesthetics of homeyness, almost un-American." But these mass-produced houses could always be built further out, and in this case, there was all of Nassau County with its "oversupply of small farms and potato fields, few of them doing much better than breaking even."Thus the conjoining of a radical new and endless supply of housing for the young back from the war, with the aid and support of generous government loan programs for veterans created a new housing boom.

And with it there was a small new newspaper with a rich publisher and ambitious, wily, and energetic young editor.

That Newsday hit the jackpot was a given. That it had a woman as its editor was a surprise; and in the sexist world of 1946 America, it was a miracle.

§ § § This story of Alicia Patterson's life and times is mildly interesting. It is fortunate for this review that I was stuck in a hospital last month for a whole week - - - it seemed a year - - - and I had forgotten to bring the 25 books on my desk at home (100 miles away). So I slogged along dutifully on The Huntress, abetted by a seemingly unending supply of morphine which is the reward for those of us who submit to the miracles of modern-day American medical practice. After a week, I had managed to dither my way all the way in the book up to page 319 (out of a total of 335) where, at last, once back in the real world, I was able to abandon it for more suitable fare.

I had picked it up in the first place because Michael Arlen had been a long-time journalistic hero of mine. In the drear days of monopoly radio and television in late-fifties early-sixties American, he was a sane critic of radio and television programming, working as a columnist for The New Yorker. He was one of the few in the country to look at the alarmingly greedy complex of broadcasters, the one that had been fomented by the American system of capital accretion, sponsored by a government which guaranteed their monopoly position; which in turn encouraged the lowest denominator programming: that which garnered the largest cash-flow.

It was all built on our country's revolting misuse of broadcasting air-space. We probably could have had as great and as meaningful radio as the media complexes in England, Canada, France, Germany or Japan - - - but instead we got a cesspool of conformity and blandness, once labeled by Newton Minow, the incoming head of the FCC, as "a vast wasteland."

Arlen's terrific writings on the media were an inspiration to those of us who tried to make something worthy out of this golden trash-heap, and I was working with an FM station in Seattle which, we hoped, would prove that a broadcasting station that set new standards of music, voice, and documentary programming could succeed; at least succeed in building a viable audience.

Sometimes our attempts to push the media envelope got us in trouble. A speech in 1968 by one of Martin Luther King's associates - - - a young firebrand by the name of James Bevel - - - landed us in hot water, meaning licensing problems with the very FCC that should have been supporting our efforts. A timely article by Arlen brought our plight to the attention of the rest of the country, at least the worldly public that represented The New Yorker's audience.

For that, we were immensely grateful, and I suspect that a later favorable ruling by the Commission in hearing on our license might have flowed from his articulate writing.

Thus, here, almost fifty years later, a rather eccentric biography from the pen of Arlen and his late wife was a must-read for me.

§ § § However, and even charitably, I have to suggest that the subject of this book is but of moderate concern, apparently inspired by the fact that Alice Arlen was Alicia Patterson's niece. Alicia's life, I claim, is interesting but in no way galvanizing, though the book does its best to make her noteworthy. Still, she was certainly no Zelda Fitzgerald, nor Carol Doda (nor Patty Hearst).

This is not to say that The Huntress is not without some merits, especially when we delve into the politics - - - and conflicts - - - between Patterson and Guggenheim (a man who was not very enamored of progressive American programs for the poor and destitute; even less interested in Patterson's friendship if not concupiscence for the lawyer and 1952 - 1956 Democratic presidential candidate, Adlai Stevenson.)

Still, there are passages here that can delight and please, with the mercurial writer Arlen at his best. Such as the tale of Alicia's "fact-finding" trip to Africa made with Stevenson (called "Guv") and several of their friends. It gives us a rich picture of Patterson's stalwart ways, but even more, of her all-too-clear no-bull-shit vision which certainly bests the astonishing blinders of the Guv.

On their last day at a clinic run by the supposed saintly Albert Schweitzer,

Patterson finally lost it with the Guv, asking him furiously if he'd noticed anything - - - not only the farmyard rags all over the dispensary, the chickens in the operating room, the chicken shit all over the tables and floors, the way the saintly doctor literally pushed and shoved patients out of the way, cursing at them in German? As Patterson later remembered it, Stevenson smiled tolerantly at her, as if she were a wayward child, and then told her proudly of his "personal moment" with Schweitzer: how he and the good doctor had been deep in conversation about world peace, a subject needless to say dear to both men, when a tiny insect had landed on Stevenson's jacket. At which point he had made, or rather had begun to make, a typical Westerner's move to brush it off, flick it away - - - gnat, anopheles mosquito, what have you - - - but Schweitzer had reached across and stayed his hand, remarking gravely, "All life is precious." (Not surprisingly this same "All life is precious" insect-protection-routine of the great doctor's turns up in numerous memoirs of Westerners in Lambaréné.) "How can you question such a man?" the Guv said to her.

--- L. W. Milam