A Song to My City

Washington, D. C.

Carol Lancaster

(Georgetown University Press)

Like so many people who want something from the government, I went to Washington back in 1959. Spent almost two years there trying to pry a permit from the feds for a FM station there. The application went in April of 1958 and by the time I quit the place in disgust in late 1959 they had not acted on it. Seems the Security Division of the FCC knew that I had worked for one of the Pacifica stations, and since Pacifica was known to be a Communist front operation, my application was doomed long before it even started. But they don't tell you that stuff (it's called "precensorship"). While I cooled my heels, I lived in squalor at the YMCA, sweated in the dust-hole of my 10' x 10' shared office on "H" Street, and wondered what in god's name I was doing wrong.When I finally went to see my representative, Charlie Bennett, he took me for bean lunch at the HR dining room and lectured me on people who wanted to destroy our government and use the very power of our government - - - like licenses for radio stations - - - to destroy it. His indirect message was so off-the-wall that it took me weeks to figure out what he was trying to tell me.

And like all the places where we meet our Waterloo, the very thought of Washington now turns my stomach. All that naked power, the misguided instincts, the frothy world where they ignore their surroundings (the powerful who live there regularly ignore if not abuse the poor and the minority . . . all the while suggesting that ours is the wonderland of world democracy).

Washington was, and probably still is a hopeless place where those who think that they can run our world talk too much and try as hard as they can never to listen.

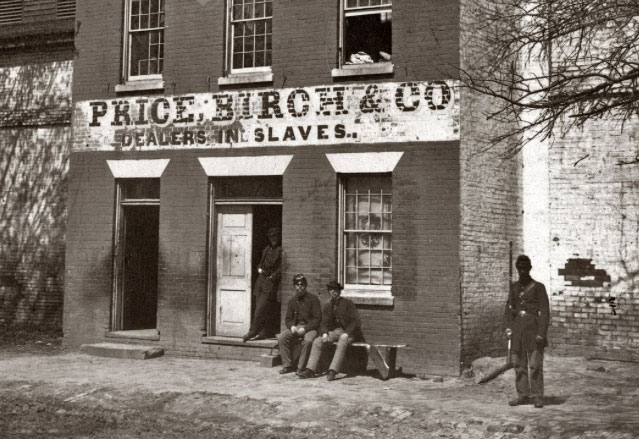

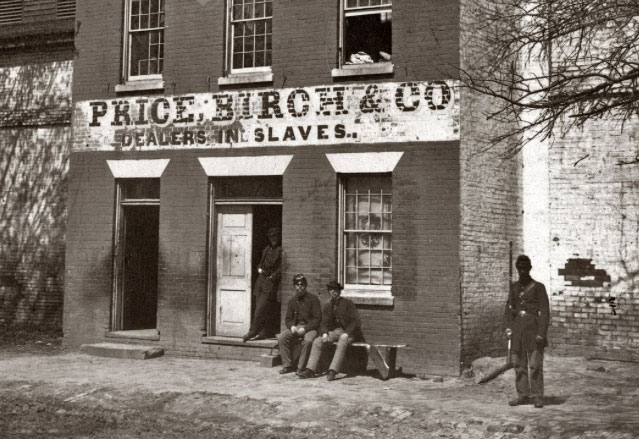

In 1958 it was especially grim, for Congress had decided at that very time to declare war on the minorities who lived in the Southwest part of the city. Using federal funds, many compact, friendly neighborhoods were destroyed, new brutalist buildings raised in their place . . . which were then sealed off by freeways acting as concrete walls to safeguard the whites who moved in there. At the same time, an exquisite inbuilt transportation system of rails, trolleys and streetcars was wiped out so that cars could proliferate to further deteriorate the atmosphere with huge injections of carbon monoxide amidst the overwhelming traffic.

Despite the drawbacks of living in a city with the worst schools in the country and with far too much hot air, Ms. Lancaster - - - a third generation citizen of the District - - - shows a passion for the place, has written a tolerable paean to it. She was born not far from St. Elizabeth's, the nut house where they stored away out best national poet Ezra Pound who they'd figured they couldn't exactly shoot for treason (he broadcast during WWII over the Italian network programs of his very nutty affection for Benito Mussolini).

Ms. Lancaster here tells us that during her childhood, "the hospital had thousands of patients"

Often during the night I could hear some of them screaming in fear of threats real or imagined.

She also reports that one day, while she was in college, "a pregnant black woman boarded the bus, and to my amazement, no one offered to give up a seat to her." To her eternal credit, she "rose and offered my seat to her."

For me in this moment, the racial divide in America stopped although thousands of Washingtonians lived with its reality daily.

One of the joys of A Song to My City are the place names. Foggy Bottom is the most favored by those of us who are looking for silly names, as well as "Swampoodle" - - - once the home for thousands of Irish immigrants, along with "Steak Alley," "Slop Bucket Row," and "Murder Bay."

Ms. Lancaster's heart is in the right place, for she deplores the civilian atom bomb that demolished the southwest, called the Redevelopment Land Agency - - - which was imposed on the voteless population of poor and minority by southern white Senators and Representatives in 1950. She reports that

Old black Washingtonians who used to live in Southwest still remember their neighborhood with painful nostalgia. By the end of the renewal project, the area was home to nearly 90 percent white, middle-class familites.

She rails against what she calls "the freeway fundamentalists" who visualized a figure-eight series of freeways, with "another freeway that would run in front of the Capitol." The plans were stopped by the rich who lived in the northern part of the city with their access to lawyers (and homegrown congressmen). But the parts that ran through poorer neighborhoods were eventually, to the city's further deterioration, actually constructed, and are vilely in place as we speak.

Unfortunately, when Ms. Lancaster starts in on Washington's "Culture," or the "Cityscape" - - - Dupont Circle, Connecticut Avenue, Massachusetts Avenue, Embassy Row - - - the book devolves into a tedious travelogue. I think we would have been far better off if she had told us more stories of growing up listening to the shrieks from St. Elizabeth's.

Fortunately, one chapter, on the city's architecture, is lively and informative. The Rayburn House Office Building is rightly labelled a place of "elephantine aesthetic banalality" and "the apotheosis of humdrum" (vide Ada Louis Huxtable). The White House itself was defined by Thomas Jefferson, who knew a thing or two about architecture, as "big enough for two emperors, one Pope and the grand Lama." (Bill Clinton who knew more of his willfulness and less of his architecture, dubbed it "the crown jewel of the U. S. penal system.") The gorgeous Executive Office Building, rising up to one side of the White House, was called "an architectural infant asylum" by Henry Adams, and, by President Truman, "the greatest monstrosity in America." It was eventually saved from ravagement by Jacqueline Kennedy, and remains a treasure-filled piece of eye-candy for those of us who are crazy about Victorian architecture (even though its architect killed himself after hearing all the complaints about it back in the 1870s).

The most vulgar of modern structures looks about as fearful as the character it was named for: J. Edgar Hoover; its architecture is known as New Brutalism.

Despite my complaints, A Song to My City is crammed with facts that are bound to surprise and please. The author claims that there were three people who were most responsible for the character of the city.

- Pierre Charles L'Enfant who George Washington brought in to do the original design (Washington insisted on calling him "Langfang").

- Marion Barry, who - - - during his first term as mayor - - - gave the city back to those who were the most important populous, namely the Blacks who represented 70% of the citizenry when he took office; and, finally,

- Alexander Robey "Boss" Shepherd, a post-Civil War millionaire who in 1870 got himself elected to the local board of public works, and, by the simple expedient of spending every cent allocated to it and using a few more million dollars on top of that (he knew that even though Congress had not approved these funds, that when the shit hit the fan they would pay the bills), he had the major eyesores demolished (including the pestiferous Northern Liberty Market), got the B&O railway to reroute their main line out of the heart of the city, paved "more than 150 miles of roads and sidewalks and installed nearly 125 miles of sewers plus gas mains, water mains, and street lights." Thus, in the decade after the Civil War, he gave the city the infrastructure it deserved, so those who were demanding that Washington be moved en toto to Ohio, Illinois, or Missouri could be sent packing.

My experience with Washington has since convinced me that we should move it to the Okefenokee Swamp National Wildlife Refuge. Let our Senators and Representatives bask for a few healthful years amidst the black bears, alligators, water moccasins, water turkeys, no-see-ums, and Zika-laden mosquitos of the Georgia swamps. Alternatively, Alaska offers us enormous territorial amplitude and hot air, a place that could use the presence of a few more citizens, for instance, in Iditarod, there on the scenic (frozen) Iditarod River.