Concrete Carnival

Danner Darcleight

(The Permanent Press)

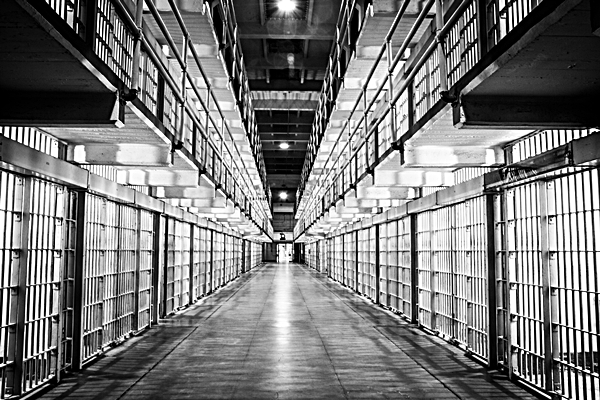

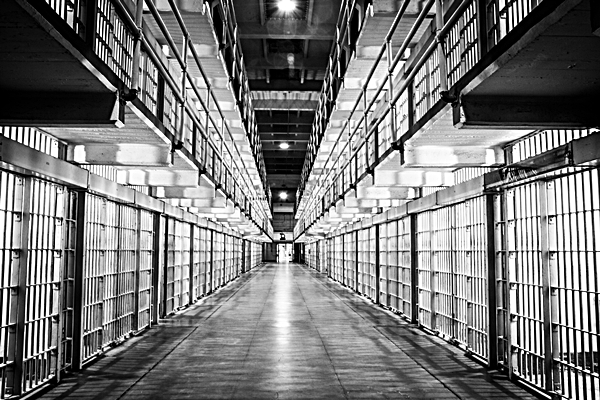

Danner Darcleight is serving "twenty-five to life" in an unnamed prison somewhere in the north-eastern part of the United States (he names it "Prison F"). The book takes him from growing up in the Dominican Republic, his entry in an unnamed college, complete with high-jinks that got him kicked out, and, ultimately, to his serious heroin habit which precipitated a murder when someone tried to take his habit away from him.A year in county jail, and the next twelve or so years in a high security state joint, lead us to understand that Prison F is possibly going to be the place where he will, one day, die of old age.

Darcleight's writing is vigorous, no-nonsense, and, after a few hours with him, may make you also think you are doing time in a high-security prison. Which, I suspect, is the point. If we want to read about prison life, we want to read someone who tells it like it is.

There among the vocabulary of that particular life - - - dompers, keeplocked, The Box, "an eighty-three" (a petition concerning prisoners' civil rights), lock-in, the gate, shanks, "cracked on" - - - we meet a survivor, one who claims that he has made it through the last decade by confronting the spooks within: not by fighting them or denying them, but agreeing, as we all eventually must, to live side-by-side with them. (Unfortunately, at least for me, is his central mot, borrowed from Nietzsche, Was ihn nicht umbringt, macht ihn stärker: "what doesn't kill you makes you stronger." Some us prefer "What doesn't kill you makes you much more wily the next time around." From what I read in these pages of Concrete Carnival - - - which includes the title - - - gets me to suspect this is Darcleight's real secret pour vivre longtemps et en bonne santé.)

§ § § Darcleight gives us a list of books that formed his own thoughts on prison life, including Genet's Thief's Journal, George Jackson's Soledad Brotheer, Jack Abbott's In the Belly of the Beast, Bell Gale Chevigny's Doing Time, and H. Bruce Franklin's Prison Writing in Twentieth Century America. Those all qualify as genuine Joint Lit - - - although as Darcleight explains, "What differentiates Genet from the pack is his portrayal of prison sex as consensual and loving."

He very much romanticized the hard scrabble life of the petty thieves he fell in with, several of whom became his sexual partners . . . Stripped of the pretense and trappings of the world, however, he experienced truly tender moments of love and companionship. It made his life behind the wall livable.

And, of course, Genet being Genet, his writings romanticize, equally, such add-ons gimmicks as a prison not unlike a holy cathedral, with holy pinched-out tubes of Vaseline . . . and, alas, body lice crawling up his lover's neck. Darcleight hastily points out that he himself is rather handsome and young looking, so he often gets "cracked on" by many would-be lovers, but that he is 100% straight. It rings true, especially when he recounts his various heterosexual adventures all while salted away in the slammer.

§ § § Darcleight has the magic ability to put us right into the cell with him, especially the great times. Yes, we learn that there can be great times in the Graybar Hotel when he and his friends Yas and Doc cook up "pitas, baba ghanouj, fried canned beef with an approximation of yogurt dill sauce, or pizza piled ludicrously high with salty meats, various cheeses, fungi and veg," or

in Doc's personal skillet, a solid old Westinghouse given him by a friendly lieutenant for whom he works . . . I made a proper focaccia, a square of just-crisp-enough dough, aromatically speckled with garlic and fresh rosemary from the plant growing in front of Doc's cell . . .

all of which make us want to Google "Danner Darcleight," find out where Prison F is, see if we can finagle a quick visit for dinner. The picture of having one's own garden for herbs between the cellblocks, and at the same time being able to scare up some cans of cuttlefish in their own ink, along with fresh zucchini flowers from the garden, and with fresh dough for garlicky breadsticks. All this doesn't exactly call up our image of the pen. Darcleight reminds us, though, that if one of the guards happens by and spots him cutting the meat with the sharp top of a tomato can, he could dub it a shiv and get him busted and sent to "The Box."

There are other good times that he tells of: during a blackout at the prison, he lit nine yahrzeit candle in his menorah (given to him by his rabbi), and explains how the other cons stopped to look with envy in his cell, beguiled by the gentle lights.

Or the times he is on the telephone with Lily, a lady in the town who answered one of his write-a-prisoner ads . . . and within a year was engaged to him (which ultimately caused the two of them considerable grief when it was found out).

But this is no don't-curse-the-darkness rant. For, as Darcleight explains, when he goes down, he goes way down, and suicidal thoughts bubble up. Until he spoke with a knowledgeable psychologist, he thought that all the rest of us automatically wonder how, when and where we should start slashing ourselves when we get depressed.

Indeed, his obsession with suicide leads to a rather revolting retelling of the time he was an ambulance driver and was called upon to help cut down a man "with a red rubber-coated wire cinched around his throat dangling from a water-stained ceiling beam."

By eighteen, I'd already encountered death in cars, on the sides of the roads, on serene jogging trails in the woods, in public spaces and tiny rooms.

He spends almost fifteen pages on the subject, which for some of us may be too much, including another quote from Nietzsche,

The thought of suicide is a great consolation: with the help of it one has got thorough many a bad night. To think about suicide isn't necessarily to commit suicide. It's to acknowledge the possibility and to acknowledge the precariousness of being alive and to affirm it.

Amidst all this, Darcleight reminds us of the main awful of being in prison. It's the presence of the other prisoners who, whether you like it or not, are going to be your close neighbors for quite some time. He spends about as much time as he does on the suicide watch going on (and on) about a very noisy neighbor, one Chuí, who sings, laughs, whistles, screams, keeps the radio on HIGH, yells to the others across the way, and in general runs at 180 decibels or so all the day and much of the night. When you're in the pokey, you'll never ever get away from the albatross named Chuí. Ever.

At the end, we are left with a fair amount of respect for Darcleight for just surviving, what with the thoughts of doing himself in, for having lived through years where heroin ran his life, helped him to violently harm some of the people he loved the most, made it so that his permanent record will forever and always be skewed by those ominous final words of his sentence: twenty-five-years-to-life.

--- Pamela Wylie