The Walls of Delhi

Three Novellas

Uday Prakash

Jason Grunebaum, Translator

(Seven Stories Press)

One of the great, out-of-this-world, indisputable gratifications of book reviewing is the chance to come across an author you've never heard of, pick up this book of his, and there you are, bewitched by the words and the structure - - - who is this guy? - - - and the scenery and the characters as they go through their song and dance of arrogance or love or nastiness or of angelic glory. There you are, caught up in it, transfixed by mere words on a page, words that cast you into a whole, new, unexpected world that you had never before imagined.That's the magic of books, of the book word, and nothing - - - Twitter, Twiggle, Giggle and Gang, iPad, iDo, iWish, stage-shows, movies, - - - nothing can match the simple book-plot for complete immersion, that take-you-over, total-ego-submersion, fat-soul splat-bomb engineering of pleasure.

It happens to all of us book crazies if we're lucky, sometimes in the far past, sometimes yesterday, maybe today and it takes us over . . . and will not let us free.

This Uday Prakash has been publishing since 1980 and since he is now in his mid-sixties we assume (we hope) he will keep on with his poems, translations, novels, novelettes, critical works . . . evidently writing up a firestorm, sloshing out the words, irritating everyone in sight, pecking at Those Others (governments, governors, officious bastards) getting them so worked up he ends up stuffed away in a jail (he was - - - for a time).

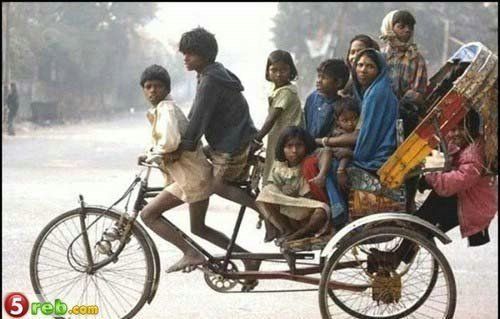

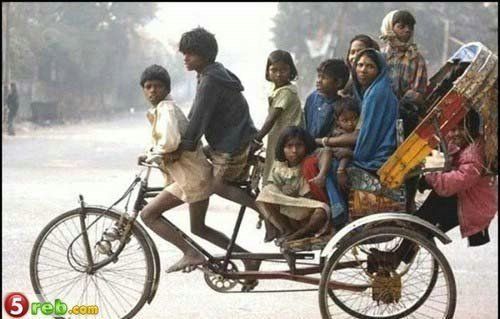

He wants you to know that he is Concerned and not just with mere words: it's all about injustice and poverty and you and hunger and me and Mohandas and the class system and all while Prakash has no problem at all knocking out a knock-down story and even when the plot-line heads off to Jersey or Uttar Pradesh or Weedville or Madras he can go on a bit about what stinks what should be righted . . . in our world, in his world, in all the world.

For instance in The Walls of Delhi he's telling us about Mohandas, this regular Biblical Job of a character. No sooner does Mohandas get out of university than he starts looking for work and what is it about him that no one wants to take him on? He's a striver (top of his class at the university, got the M. G. Degree "right here in the Anupper district . . . graduated at the very top of his class") and yet no one wants him.

He's courteous, well-spoken but (can it be?) maybe the gods are lined up against him for reasons we can't fathom. Even when he gets an offer from the Oriental Coal Mines that pays 10,000 a year it seems that the guy who hands out the jobs there has a friend, Bisnath, and Bisnath pretends he's Mohandas and with a few bribes here and a party or two there this bloody Bisnath ends up stealing the job, then he lazes about, doing nothing but taking the rupees that should have gone to Mohandas.

When Mohandas goes again and again to the offices of the Oriental Coal Mines they don't believe that this fellow in hand-me-down clothes is Mohandas, to the point that he himself begins to doubt that he is who he says he is: maybe he's someone else.

He was the Mohandas who'd been denied a job because he had no connections, no pull, and no money to use for bribes. He wasn't a member of any gang or group or mafia because he didn't belong to a caste that had any power. He knew full well that he and countless others like him had been cheated and lied to and tricked for many, many years, but he had no means to do anything about it.

Poor Mohandas. For the long course of his story, in which he tills his tiny garden hardly bringing enough for the family to eat and his grandmother goes blind, his father dies, his wife gets older and sadder and his son begins to look beaten down too. Then again comes someone who says, Mohandas, I've heard that the Oriental Coal Mines has just found out that you were screwed but I've heard that if you go back up there and tell them who you are, that they will . . .

And here's hope springing up like the toadstools in the shit under the neem tree so Mohandas labors his way up to the office of the mine again and gets swatted down again just like that, Bisnath and his friends laughing up their sleeves, throwing yet another party to show how they fooled him again, and even the author Prakash seems to get pissed off like the rest of us, not only mourning the turn of events but then going off in a snit himself about . . . well, Christ! - - - just you try to be a writer in India, where

Another book of mine came out during that time that chipped away further what tranquility I had left. Well - - - connected and high caste writers from Delhi, Bhopal, Lucknow and other major cities began calling me a rabid dog, fascist, copycat, thief, Naxalite, communalist, feudal, affluent. My newspaper column was dropped, payments cancelled, and the rumour mill spun out such awful stuff that I nearly went mad. They were dark days. My sleep was racked with nightmares. I felt as if my body, now skin-and-bones, was pushed up against the wall waiting for death in a solitary confinement cell in some labour camp, like Osip Mandelstam. Or sitting quietly on a chair in front of the Sharda mental hospital: a single grain of rice gets stuck in my windpipe, my breath grows erratic and I cast my eyes wildly around as my death approaches. Like the Hindi writer Shailesh Matiyani, who died in that hospital. Fascism was right in front of us with a new look. The power of illegal capital and criminal Violence was hiding behind the veil of the great ideologies of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, until it consumed and reduced to ash the great philosophies of the past two centuries in the irrepressible fire of its base ambitions and desires.

And then, just to put in that little spice of you-can't-believe-this, buddy - - - up the ante, make us doubt our doubting . . . "and a criminal complaint is lodged at the police station, it's done so in the name of Mohandas, since most of the people still know Bisnath as Mohandas. Then it's poor Mohandas, the real one, who gets arrested and dragged off by the Purbanra police."

Harshvarddhan's eyes filled with tears of helplessness. "Bisnath colluded with police inspector Vijary Tiwari and bought off the guards at the station with food and wine, and now they've beaten Mohandas within an inch of his life. They broke his hands and feet and he can't walk. And four days ago his mother Putlibai fell into a well and died. Kasturi is cobbling together whatever she can to put bread on the table."

"I looked up; Mohandas was approaching, limping heavily. He was not wearing the washed-out, patched up pants and torn checked shirt, but only a loin-cloth. His hair had fallen out, and he wore cheap round eyeglasses. He walked slowly, using a walking stick, shuffling along like an old man."

"Ram Ram, uncle!" he said upon seeing me, joining his palms together in greeting. The deep wrinkles on his face were a monument to his suffering and defeats. He looked like a very old man, maybe eighty or ninety. He sat down on the ground, using his walking stick as a support. But the gruff voice that came out of his mouth with a groan wasn't our local tongue, but Hindi, the "national language." He said: "I take your hands and beg: please find a way to get me out of this. I am ready to go to any court and swear that I am not Mohandas. My father's name is not Kabadas, and he is not dead, he is alive. They really beat the hell out of me, the police did, on Bisnath's order. They broke my bones. It hurts to breathe it's so bad."

"I noticed his lips were cut badly and he was missing some teeth; they must have smashed them out in the police station. He could barely put two words together."

"Whoever wants to be Mohandas, let him be Mohandas. I am not Mohandas. I never did a BA. Didn't come out on top of my class. Never was fit for work. Just want to live in peace. Leave me be, no more beatings. If you want something, take it. Take what you need and fill up your homes. But leave me to my life and toil. Uncle, please stand by my side."

And then Prakash throws in this blockbuster of an off-the-cuff aside, stuck in there with such finesse that we go, oh, yeah, I see, now it's time to forget about our Job, to talk about archers . . . and dams, an blocks that fill the beautiful old countryside with dying water,

It was the time when at the top of a hillside near Bharuch stood a thirty-year-old Dhanuhar archer named Raghav. Night after night he'd stay up late whittling down shaft after shaft of bamboo into arrows. He drew the bowstring taut and shot arrows at the sky, then ran down the hill to retrieve the arrows that'd come back down.

Again and again and again - - - countless times he fired arrows at the sky and retrieved them from the dirt.

But then the arrows began to be submerged under water, and it became difficult to find them and pull them out. The fields of the valleys that lay between the mountains were filling up with water: inundated, a massive flood. Village after village began to go under, and trees, too. North and south and east and west were going under; all memories were going under.

Yet thirty-year-old Raghav kept shooting arrows into the sky and running down to retrieve them as long as he himself wasn't swept under.

Where is Raghav now? Just where he was, where there's now nothing but water. A vast, bottomless sea where electricity is created. There once was a hilsa fish in Bharuch. The greatest fish in the rivers of India, the most magnificent in the world. The hilsa is only able to survive in the fast moving current of a river.

The hilsa at the dam is sick from the polluted water, and has probably died.

Enough? No, not enough. Now comes this - - - shall we call it? - - - aside within an aside, a brief autobiographical footnote about the author tucked in here. For he had a Mohandas experience too, got salted away in the pokey for awhile, for his writings:

It happened at the same time as when I was writing this story in a language that imprisoned me inside just like Iraqis were imprisoned in Abu Ghraib. Or like Jews in 1943 were imprisoned inside a German gas chamber. Or like a drowned hilsa fish in dirty, stagnant, polluted waters. Or right now like Raghav Dhanuhar, still fighting.

Now, back to Mohandas:

This was the time of Mohandas, of you, of me, of Bisnath, of what we see this very day when we look outside our windows.

And the time everybody knows as the first decade of the twenty-first century, when all of us were celebrating the one hundred and twenty fifth anniversary of the birth of Premchand, the King of Hindi Fiction.

But really, tell the truth: Doesn't the name of Mohandas's village, Purbanra, remind you even a tiny bit of the Mahatma's Porbandar?

§ § § There are two other novelettes here. One is about a simple sweeper named Ramnivas who at work one day at the club for the elite and happens to knock his broom against the wall to make it sit better and the wall breaks a bit, he peeks in and sees thousands and thousands of rupees stacked up there and he reaches in and takes out a couple of packets, wraps them in a paper and he - - - a man who "was known for being such a penny pincher. She never liked the way he'd come around Sanjay's and try every trick in the book to convince someone to buy him a cup of chai, or a bidi."

And then, after his discovery he "didn't just include Sanjay and Santosh in the round of chai, but also Devi Deen, the cobbler, and Madan, the bicycle repairman. And not just plain old chai, but the deluxe brew - - - strong with cardamon."

See how Prakash does it? Those details. The transformation: even Mandan, the bicycle man, the bicycle man gets some. And not just plain old chai, "but the deluxe brew - - - strong with cardamon."

And you know, you just know . . . how it's going to end.

And it does.