Inventing a Better Mousetrap

200 Years of American Industry in

The Amazing World of Patent Models

Alan & Ann Rothschid

(Maker Media)

The U. S. Patent Office's existence was made possible by the United States Constitution, in Article 1, Section 8, wherein one of the powers of Congress is defined as follows:The Congress shall have Power . . . To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.

Thus the U. S. Patent and Trademark Office. Up until 1880, anyone who wanted to obtain a claim for patent protection had to file, along with the appropriate paperwork, a model no larger than three cubic feet (12 inches by 12 inches by 12 inches) to the office in Washington D.C.

.

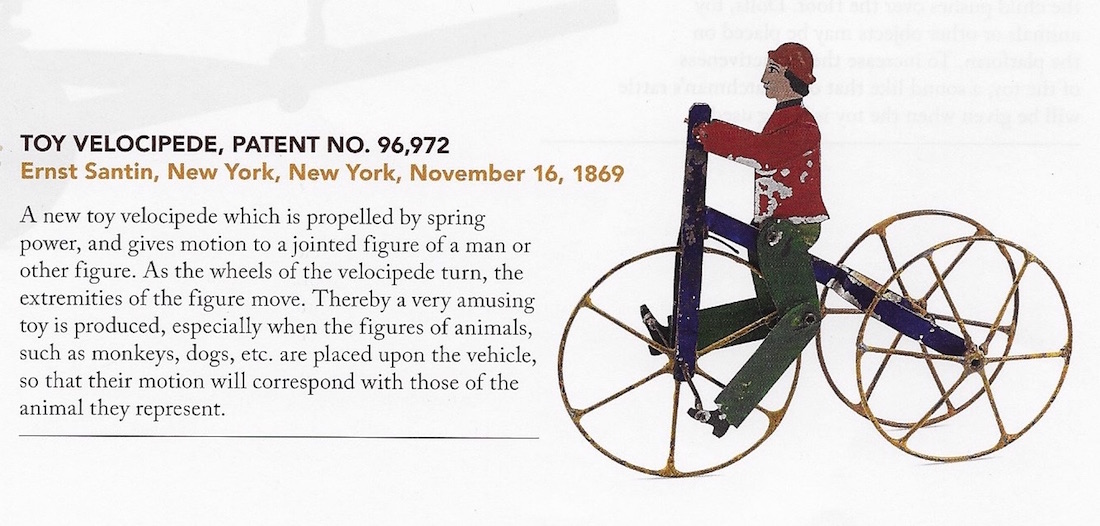

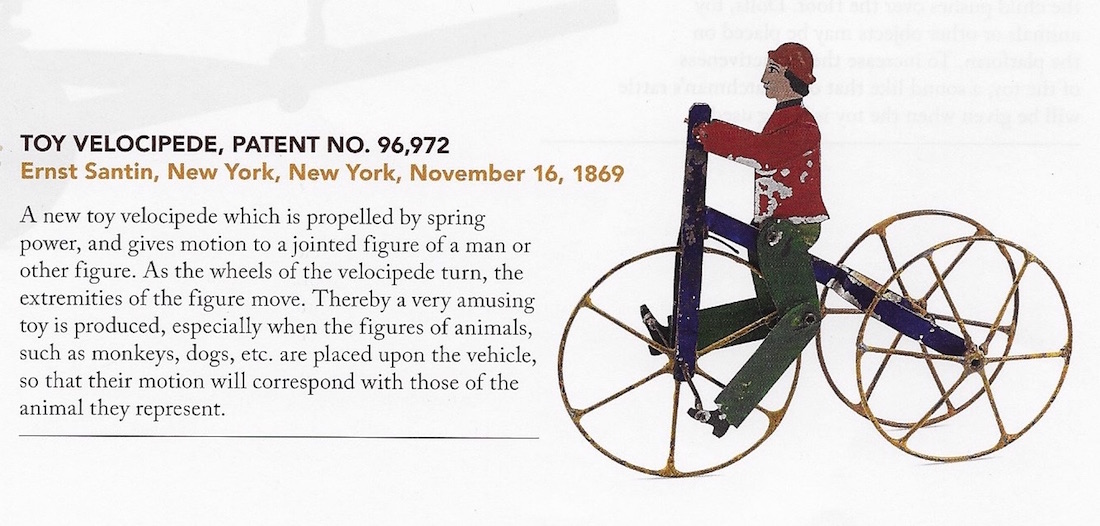

No matter if you were patenting a holder for a "sad iron," or an earth scraper, or a molder for candy whistles, or a ratchet drill, or a set of playing cards, or "a violincellodian," or "self-levelling berths for ships," or a pen holder, or (unbelievable) a twelve inch long representation of a 1,000 foot long bridge to go over the Ohio River: in all cases you were required to fabricate a teeny-weenie model to submit with your application.In this spacious book, the authors have collected some 750 color photographs of what is a small - - - but wonderfully diverse - - - collection of artifacts from twenty-two different disciplines, including transportation, music, agriculture, sports, healthcare, toys, marine and navigation, and fifteen other fields to show the diverse if sometimes balmy world of 19th century American invention.

Here, in this volume, these models are tastefully fitted, three to the page, with a brief name of the product, the patent number, the name of the inventor, and the city, state, and date of application. There is also a brief description to let us visualize the raison d'être for some of these submissions.

For instance one Moses Bensinger of Brooklyn, N. Y., applied for and received Patent # 159846 for a "Pigeon Starter." The authors explain, "At the time this patent was issued, live pigeons were used for target practice, and placed in traps dug in the ground, just below grade level."However, opening the trap was often not enough to make the pigeons fly up or even leave the trap. Yelling or throwing stones at the pigeons were common methods of startling the pigeons, but affected the shooter's concentration. This patented pigeon starter made a loud noise and included a cat-like creature that moved from a crouching position into an upright stance, to startle the birds into flight.

"Cat-like" is generous. From the photograph, we can see a stiff-legged creature, a four-legged Frankenstein more in the shape of a crocodile. It is spooky enough when shown in the crouched position, but truly startling when standing upright, enough to frighten pigeon and shooter.

The authors include a short biography of the inventor Moses Bensinger (1839- 1904), who grew up in Cincinnati, married into the family of one John Brunswick, and Bensinger went on to greater things than spooking resting pigeons. Ultimately, Brunswick created the J. M. Brunswick Billiard Manufacturing Company, which he left to Bensinger in 1890. Bensinger filed a pile of patent applications for improvements for your common billiard table.He was evidently a sportsman as well, known for his ability to shoot live pigeons from the sky after they were frightened out of their minds by his officially patented pop-up pigeon starter.

§ § § If it was in the public interest, you could even build a better mouse-trap. John O. Kopas of Washington, D.C. applied for and received patent #102,133 in 1870 for a machine that could "capture four or five mice." When the cheese holder was disturbed, the creature (shown in the model as a tiny, friendly mouse) would fall through a trap-door at which time, "the next baited platform rotated into place. The mice are removed from the bottom of the trap by a sliding door."

The authors then go on to fill us in on one of our leading light's original thoughts about creating such an item: "Ralph Waldo Emerson, the great essayist, said in a lecture in 1871,"If a man can write a better book or preach a better sermon or make a better mousetrap than his neighbor, even if he builds his house in the woods, the world will make a beaten path to his door.

The authors go on to comment that "4,400 inventors tried making a better mousetrap and received patents from the U. S. Patent Office. Only about 25 were ever profitable."

In 1875 John Mast of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, invented the "snap trap." It was very effective, simple in design and cheap to manufacture. Today the Woodstream Co. manufactures this trap under the Victor name and sells over 10 million a year, which is over 60% of the world's market for mousetraps.

This aside ends with a cryptic statement, to wit: "The trap snaps shut at 38,000 of a second." Say who?

Here amongst the Mirror Adjusters, Hat Holders, Lap Boards, "Springs and Barrels for Time Keepers" and the "Boot Jack and Burglar Alarm Combined" is a section dedicated to Healthcare, complete with quotation from Mark Twain,The only way to keep your health is to eat what you don't want, drink what you don't like, and do what you'd druther not.

This is followed by items like Pill Machines, Portable Commodes, Fracture Boxes, Artifical Palates, an Invalid's Table and Club Foot Shoes complete with a key so the foot could be twisted back to its more or less normal shape.

The glory of this section is Theodore F. Engelbrecht's Artifical Leg, Patent #37,282. It is of a beautiful hue, looking to be made of pure gold, shining brightly on its modest wooden base, bringing us to think that the user would surely want to go about sans pants or skirt because of its great golden hue.

§ § § This stout volume is a pure delight, giving us a peek into what those who thought of themselves as "inventors" - - - daring, unstoppable, part-dotty - - - assuring us that problems could be easily solved to bring profit and acclaim to all Americans with their can-do, change-the-world, damn-the- torpedoes stance . . . one so familiar to those of who have a fondness for the cheerful nineteenth century filled as it was traveling salesmen, hustlers, buskers and oh-so friendly montebanks.

--- Pamela Wylie