Twelve Great Books from

The First Half of 2016

When we review a new title,

we always look for a little

something that makes it special.

These titles we give a star in our

General Index

which means, as that plump

Michelin Man has it,

that it's vaut le voyage.

Here are a dozen, more or less,

from the early days of 2016.

Why Walls Won't Work

Repairing the US-Mexico Divide

Michael Dear

(Oxford University Press)The trouble with walls, according to Michael Dear, is that you can sneak under them, frame doors through them, or jump over them. Already, in the existing parts of the Berlin Wall between Mexico and the United States, there are special doors placed in such a way as to not be noticeable . . . doors that can be opened quickly and quietly at night when the helicopters are gone for people to zip through. Over the last few years, over sixty tunnels running between the two countries have been discovered, with exotic ventilating equipment and well-disguised entrance and exits.How many more are there? The exact quantity has been predetermined by the well-known "Ambient Roach Paradigm." ARP states that if you see five roaches in the course of a day, you have an infestation of approximately twenty times that figure, perhaps 100 roach families meeting their production quota in your kitchen, behind the cooler. By this logic, we can predict another 1,200 tunnels between Mexico and the United States, still to be discovered, for hundreds of thousands to slip through. And more on the way . . .

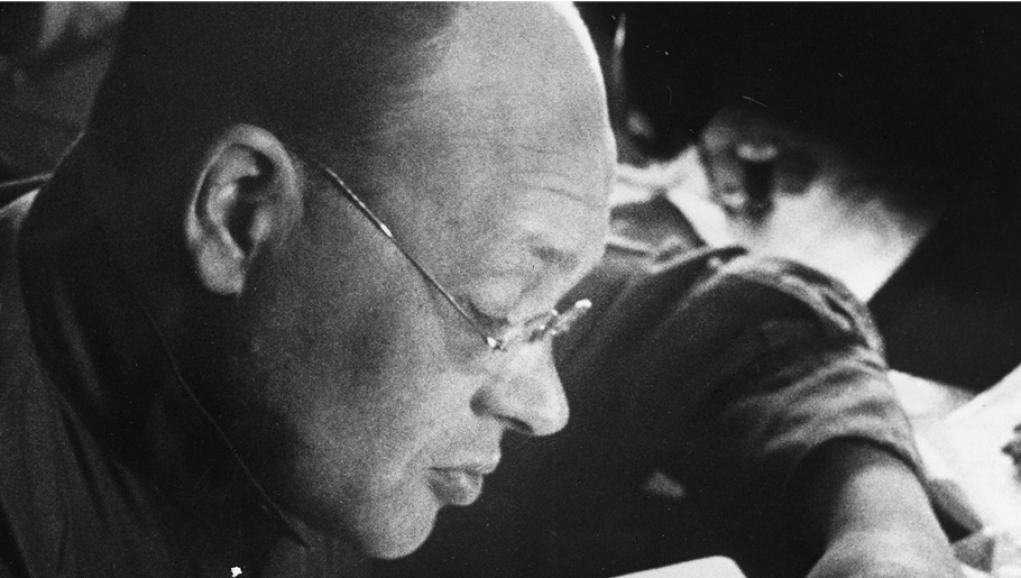

Dear is much taken with Dwight Eisenhower's final speech, the one he gave as he was preparing to leave office in 1961. The president warned of an upcoming oppressively expensive finance unit of American military, the "military-industrial complex,"

The conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new to the American experience [Eisenhower said]. In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.

The prescience of this warning --- from an ex-military hero --- was and is extraordinary. And was universally ignored. The United States Military Budget for 1960 was slightly over sixty billion dollars --- $60,000,000,000. The present figure is close to seven hundred billion dollars --- $700,000,000,000. Rep. Ron Paul reported that "We occupy so many countries . . . We're in 130 countries. We have 900 bases around the world." This would tend to confirm Eisenhower's fears.

Dear suggests that a similar complex has come into existence on the United States - Mexico border. He calls it the "Border Industrial Complex,"

the multidimensional, interrelated set of public and private interests now managing border security --- encompassing flows of money, contracts, influence, and resources amount a vast network of individuals, lobbyists, corporations, banks, public institutions, and elected officials at all levels of government.

Go to the full

reviewHot Milk

A Novel

Deborah Levy

(Bloomsbury)Take family dynamics. There in Almería, Sofia suddenly finds herself in love with Ingrid. Ingrid is almost Wagnerian, a woman that you expect to appear on stage with plaits and helmet, riding a massive horse (she rides a big Andalusian horse). Too, Ingrid has, only for Sofia, kisses sweeter than wine.They're in love, so one day when they're on the beach Sofia shows her affection for Ingrid by grabbing her cell-phone and throwing it in the water where "We both watch it float for three seconds with the medusas [jellyfish], pulsating and calm, circling the phone, then it sinks." Ingrid says to Sofia, "you are unruly and chaotic, you are in debt and your beach house is untidy. Now you have thrown my phone into the sea. I don't know what to do, because I'm going to lose work."

"Your clients will have to speak to the fish" says Sofia.

§ § § You think that's bad? Mother Rose has been complaining to anyone who'll listen (especially Sofia) for months possibly years about her feet, saying she is going to have them amputated because they are so useless to her now. This is despite the fact that earlier that day, Sofia saw her walking along the shore of the beach. "She held a hat in her left hand. Yes it was her, and she was walking. At first I thought she was a mirage because I had been in the desert sun all day, a hallucination or a vision or a long-held wish. She was walking the walk, oblivious to everyone, and she did not see me."

That night, they go for a ride in the car --- wheelchair and all --- and Sophie stops on the freeway to Rodalquilar, says she wants to watch the sunset.

There was no sunset to look at but Rose did not seem to notice.

Out came the wheelchair and fifteen minutes of heavy lifting, Rose leaned on my arm and then on my shoulder as she lowered herself into it.

"What are you waiting for, Sofia?"

"I'm just getting my breath back."

A white lorry was making its way towards us in the distance. It was loaded with tomatoes thrown under plastic on the sweltering desert...

I wheeled my mother in to the middle of the road and left her there.

Go to the full

reviewFear and the Muse Kept Watch

The Russian Masters ---

From Akhmatova and Pasternak to

Shostakovich and Eisenstein ---

Under Stalin

Andy McSmith

(The New Press)The one writer who comes out as truly heroic here is Anna Akhmatova, whose work was banned in 1925 and --- after the seige of Leningrad, where so many perished of starvation or sickness --- was assumed by many to have died. One of the most moving passages in Fear and the Muse involves Isaiah Berlin. He was a visiting don from Oxford who, when he arrived in Leningrad at the end of the war, asked if there were any writers still lived there, and was told about Akhmatova. "Is she still alive," Berlin asked, surprised.He was given her address, and arranged to meet her that afternoon. "The person who greeted them was not the charismatic poet whose angular features were immortalised in a 1914 oil painting by Nathan Altman but a stately gray-haired lady with a white shawl across her shoulders, a noble head, an unhurried manner, and a face that expressed a lifetime of suffering."

When Berlin met her, "Her manner was so regal and severe that he bowed to her, as if she were a monarch." Their conversation --- which lasted most of the night --- was recorded, in detail, by Berlin. At one point, she spoke lines of her own, including her unfinished "Poem Without a Hero," and, Berlin recalled, "I realised I was listening to a work of genius." She also read Requiem from a manuscript, "breaking off to talk about the years 1937 - 1938 and the queues outside the prisons." As punishment for her, Stalin had seen to it that her son, Lev, was imprisoned in Leningrad, and ultimately shipped off to the gulag at Norilsk, "the most northern human settlement in the world."

And when Berlin asked her about Mandelstam, "a long tear-filled silence followed until she begged him to change the subject."

The man who arrived unexpectedly from a country where people speak their minds freely, who brought news of friends she had not seen or heard from in a quarter of a century, was the last great love of Akhmatova's life. On the manuscript of her "Poem Without a Hero," she wrote a third and final dedication to the "Guest from the Future," an obvious reference that was considered so dangerous that the Soviet editors of her posthumous collected works reluctantly left it out. He is probably also the person she was referring to in these lines written in 1956:

He will not be a beloved husband to me

But what we accomplish, he and I,

Will disturb the Twentieth Century.Go to the full

review

Dinner with Buddha

A Novel

Roland Merullo

(Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill)In Northern Colorado they get waylaid by a mother with two young boys who have a flat tire. After fixing it --- Rinpoche pausing to be fascinated with the car's "chack" --- mum insists they come home with her for pie. Once there, in the ratty trailer, in the dusty valley, as they are stuffing themselves with cherry pie and ice cream, Dad drives up, straight from work. He greets the visitors --- our middle-aged New York cynic and his bald friend in saffron robe --- with a cheerful "Get out . . . We don't need no religion bullshit in here."Wife: "Ethan! If it wasn't for them we'd still be out at Bog's [restaurant]."

"Get out, queers," Dad said. He swings, hits Otto glancingly with a six-pack of beer he's carrying, at which point the two boys, one nine, the other thirteen, obviously used to the spazz routine, take Dad down, pin him to the floor: "they were punching, and he was swinging his arms." The older one slams him in the groin which slows him down, and Otto says,

I watched the scene a few feet in front of me as if it were a film playing on the television and I'd slept on the couch after a night of drinking and had just awakened. From what I could tell, Dad was taking somewhat of a beating, though they made a point, it seemed, of not hitting him in the face. There was a great deal of cursing, an abundance of cursing, most of it from Dad's mouth. Edie [the wife] had started weeping in a pitiful way. Rinpoche had begun chanting --- a prayer for peace it must have been. I'd seen it work in the past, this time it didn't work, at all.

"The main problem, at that point, was logistical: The tangle of bodies, still writhing, though Dad had almost given up, stood between me and the door."

Dad is lying flat, glaring at the two visitors, cursing them. "Rinpoche stepped over them first but instead of heading right out the door he knelt down and put his mouth close to Dad's ear. I couldn't hear what he said, just wanting to get away from there before anything worse happened, before Edie came out of the bedroom with a gun, or the boys started to pull out their father's teeth." Finally, back in the car, Otto and Rinpoche roar away.

Rain Dogs

A Detective Sean Duffy Novel

Adrian McKinty

(Seventh Street Books)The final hook for me in Rain Dogs was what we always call "the throw-aways," touches that may be frills, but light up the way to the inevitable conclusion.

- Women in Ireland who need an abortion have to get out of town. Like the legislators in Topeka, the men who run Ulster have staked their ownership of every woman's private parts: no abortions allowed. So the poor unfortunate women have take take them on the overnight ferry all the way to Liverpool, to get a D&C.

- Duffy makes an investigative trip to Oulu, Finland. Didn't like it. He claims it was a pilgrimage more awful than Apsley Cherry-Garrrard's The Worst Journey in the World.

- There are reasons not to trust rectal temperatures taken on a corpse that has been dead for several hours. We get to spend a couple of pages here with Dr Beggs, the county pathologist who has an elaborate theory on all the variables, mostly in the "linear part of the sigmoid cooling curve."

- There is some speculation here about the murmuration of starlings, how a flock will move in exact synchronicity with each other, a theory that also may apply to the works of criminal detectives.

- And pregnant women? "Never argue with a pregnant woman," says Duffy, with his ex-love, there in Liverpool. Then,

- "Never argue with a pregnant woman about to become an ex-pregnant woman." He dubs it "an ontological and metaphysical disaster area."

- And the explanation for the title of this whole opus? Since I won't put up with any music composed after Antonio Caldera (c.1670-1736), I had to consult the Googlean oracle. It told me that "Rain Dogs" is an ancient ditty (1984) recorded by someone named Tom Waits --- related, I suppose, to the same Wait found in your typical lowlife bar like mine, the Bar None: "Our credit manager is named Helen Wait. For credit you should go to Helen Wait."

- Whoever he may be, Tom Wait(s) wrote "Rain Dogs," which is said to have to do with "the urban dispossessed" of New York City.

- Now that's something I can dig. As does, I guess, my this week's new favorite author, Adrian McKinty.

- Do people still say "dig?"

Go to the full

review

Tales from the Couch

A Clinical Psychologist's

True Stories of Psychopathology

Bob Wendorf, PsyD

(Carrel Books)Tales from the Couch is a hotbed of MPDs, depressives, would-be suicides, general weirdos, border-line personalities, and paranoids who would certainly drive the rest of us bonkers. And as we follow them and author in his practice, we find ourselves thinking that they are fortunate to end up with one who appears to be creative, professional, honestly dedicated to trying to relieve others' pain.For instance, he is, as many in his profession, haunted by would-be suicides, seeing them as the ultimate failure of the trade. He also sees them as being the ultimate blackmail threat: if you don't do what I want, I am going to off me . . . and you're the one who made me do it. He rightly sees the threat of suicide "part of an extortion racket," suggests that people who make that vow are often "too selfish and too chicken to sacrifice themselves over another person." "I've seen too many family members and friends who've been devastated by a suicide. It's an injury that is not soon healed."

We tend to think of suicide as an act of depression and desperation, and most times it is. But it is also an act of hostility and aggression. It is in fact an act of murder, even if the life you take happens to be your own. Moreover, it's often done to hurt others, the ultimate in passive-aggressiveness.

There's a terrific dose of no-nonsense here, along with a feel of a wondrous sense of one-upsmanship that allows him to use play --- play in the best sense --- to the benefit of his clients. One of his Latino clients was afraid of being seen going to Bob's office in the mental health clinic, afraid that his friends would think of him as being "loco." So they went once a week to good cheap restaurants and cafés: "we conducted his therapy over lunch." Not very ethical, probably even prohibited in the psych-biz now, but

Gilberto felt respected and cared for and would likely have dropped out of therapy if forced to come to my office. Besides, I frequented the same honky-tonks and dance halls he did.

"Being Chicano, Gilberto knew all the best Tex-Mex restaurants, the ones that hadn't gotten discovered, appropriated, and ruined by Gringos. So the arrangement worked well for both of us."

What is best about Wendorf is his ability to tell you about a case study, tell you what he believes is happening, then boil down the psychological discipline (without the ridiculous language of DMS-5 --- the official Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) to make it meaningful for the rest of us. He has the further advantage of being a fun and funny writer.

For instance, family systems therapy had its heyday thirty years ago under the aegis of Salvador Minuchin, Murray Bowen, Carl Whitaker, and Virginia Satir. They saw the family as a union of individuals that could, at times, go terribly bad and wrong. It is, Wendorf says, a matter of patterns. "The real pathology is in the way family members relate to each other."

Who actually becomes symptomatic and shows up as the "patient" is somewhat arbitrary and she may even be the healthiest one in the family.

Go to the full

reviewIn Gratitude

Jenny Diski

(Bloomsbury)There is a schedule for her chemotherapy, and then antibiotics to fend off the opportunistic infection, but the physician has to change it, suggesting "that my body isn't playing strictly to the prescribed rhythm."The body, we shouldn't be surprised to learn, has a mind of its own.

The treatment itself? "When I look back from my current spot in the land of hiatus, the entire process makes me think of clubbing baby seals . . . small, helpless, newborn, cute, white ones with big watery eyes. This probably isn't the right attitude to cancer treatment. I'm feeling oppressed."

Death? What do we think of death --- hers, yours, mine, everyone's? I recall one of my friends saying that he couldn't believe in death "because I can't imagine a world without me in it." Diski --- for once here, faced with it, seems to feel at a loss for words. She writes,

Without a notion of a holiday-camp heaven, something I seem never to have had, I was left with a new and special kind of endlessness, like infinity, but without you. By which I mean me. You and then not you. Me and then not . . . impossible sentence to finish. The prospect of extinction comes at last with an admission of the horror of being unable to imagine or be part of it, because it is beyond the you that has the capacity to think about it. I learned the meaning of being lost for words; I came up against the horizon of language.

Reading In Gratitude (gratitude for what: for what she had for so long? for what she lost? for our being a loving audience, keen to read every word?) --- reading this puts us in a different space from being involved in the death of someone we have known, lived with and possibly loved . . . outside of books. For me, oddly, Gratitude brought me back to Samuel Pepys. As with Diski, we follow someone way off over there through days and nights and lusts and angers and greed and grief and then one day, he suddenly announces, on the page, "This is my last entry."

Why? He can no longer fill it with words because of his encroaching blindness . . . and the suddenness of it interrupts the terrific journey we've had with him; leaves us bereft. We've gone to the limit with him, page after page, gotten to where we genuinely want more of him. And suddenly, we are cut off, without --- as they say in law --- without "recourse."

We want to sue.

In the same way, we have patiently and lovingly gotten into what we might think of the heart of this Diski (confessional; funny; awe-inspiring; insightful) and here she gets near the end, and turns sassy on us.

Much of this writing appeared, regularly, in The London Review of Books, so she takes advantage, at the end here, to stick in some more rude, cheeky, Diski-isms: "Incidentally, anyone wanting to send me a last Christmas sorry-you're-dying prezzie, I want a silk or organic cashmere something, so I can waft my way through the box sets and die happy at having seen the last episode of The Bridge 3 in cozy things that I can stroke . . . Top of the list (after the sumptuous silk) is that our neighbors not start building work till I am gone. Or at least stop them playing Radio 1 [the BBC home-folk bourgeoisie channel] . . . For several days now I've been feeling as if I'm on a holiday, a short one coming to its end.

As one might sit on the edge of a chair that is waiting for another occupant to take it over. It's the strangest of strange feelings. Best travelling clothes, a ticking of a clock that will go on ticking after you leave and after the next occupant too. . . . The clock that clicks as generation after generation passes by.

"It is, of course the ticking, tocking of this everlasting, or outlasting, clock that keeps everything seeming so orderly, that is, you realize, keeping the time."

About time too, someone says in the distance, and you realize that it is about time. Catch a handful of salted peanuts, then pick up your cheap suitcase for the forward journey.

Go to the full

review

Red Cavalry

Isaac Babel

Boris Dralyuk, Translator

(Pushkin Press)The Pan General drops the reins, trains his Mauser on me and makes a hole in my leg.'All right,' I think, 'you're mine, sweetheart --- you'll spread those legs.'

I go flat and plant two rounds in the little horse. I was sorry about that stallion. A little Bolshevik, that stallion was --- a regular little Bolshevik. All coppery like a coin, tail like a bullet, leg like bowstrings. Thought I'd bring him to Lenin alive, but it didn't work out. I liquidated that little horse. It tumbled like a bride, and my ace come out of the saddle. He took off running, but then he turned around again and made another draught-hole in my figure. So now I've got three decorations for action against the enemy.

It's the arch mix of love for a gorgeous horse, touched by irony, "a little Bolshevik," "bring him to Lenin" (this is 1920) which, when shot, "tumbled like a bride."

And then "my ace" shot him again - - - gave him "three decorations:" these are the stark, stolid words of a soldier. This paragraph emerges as pure poetry, wrought by one who has the ability that Keats labelled "negative capability," the power to contain one (or more) contradictions in a few words. Contradictions of language and thought and philosophy and reality and romance, all soldered (or soldiered) together in a blending of incongruence . . . words united in an artistic act of defiance, both literary and military.

There are many passages in Red Cavalry which will float over our heads for, after all, we are in the midst of an eloquence from a century past, words of wars and cultures and revolutions and peoples and prejudices that must be hard to conceive of now. But the truth hides in plain sight throughout, giving the reader a rhetorical gold mine, provided by a man whose words were so powerful that they would ultimately kill him; one who was capable of insulting the powers with words that would lead to his own demise.

And, at the same time, being one who was capable of telling the story of his old friend Lyovka, dying as well:

"To the last," Lyovka repeats ecstatically and stretches his arms to the sky, gathering the night about him like a halo. The tireless wind, the clean wind of night, sings, filled with ringing, gently rocking the soul. Stars blaze in the dark like wedding rings; they fall on Lyovka, get tangled in his hair and face in his shaggy head.

Go to the full

review

The Gambler's Apprentice

H. Lee Barnes

(University of Nevada Press)Dialogue out of the old school, as good as L'Amour, maybe even better. He was good at pushing the action, too, as good as Barnes. In forty-nine chapters, Willy gets rolled, shot at, beat up, chased, near drowned, almost steals another man's wife, damn near killed. He is obviously built like those James Bond characters, near indestructible, but somehow more interesting.And can he deal. A guy named Sonny showed him how to play cards, move them around unseen to the top or the bottom of the deck. Sonny also taught him the philosophy of the gambler who must survive the implicit violence of the gaming table. He "spoke tirelessly of the green-felt table as 'the ether of human existence,'"

each hand bringing hope or despair, reward or rejection, failure or triumph. He sometimes added to those joy and depravity.

Willy? He saw it as a business, nothing more, "the best hand or bluff winning the pot. Money was the proof of his opinion. Take that away and cards were a waste of time. A man could better spend his earned money in some other enterprise." And we are right there, the particular smell of the room, the tension, the men, "their clothing, their habits, their vocations --- leather and sweat, cigar and pipe smoke, beer and whiskey, and the dirt-and-oil odor that lingers on those who do hard labor."

Go to the full

reviewThe Curse of Jacob Tracy

Holly Messinger

(Thomas Dunne Books)This show-stopper occurs in the first few pages of The Curse of Jacob Tracy, and it just goes downhill from there. But it is a helluva good ride.We get blue monsters attacking a train, trying to eat people (they are hungry; they're called keung-si and they're Chinese in origin, which may make them as dangerous to some loyal Americans as the Maoists). There is too a young girl made crazed, murdering her kindly family . . . and a charming if sullen Mormon lad who, after he gets stung by the Russian spirit-master, turns on Trace, tries to bite him. How would you like it if someone you were fond of suddenly starts slavering and going for your jugular?

These monsters are everywhere, if you know how to spot them, which means that as we trail Trace going about in the west territories in 1880, we never know who is going to sprout pointy teeth and develop blood-lust and strange lupine features, turn all furry, try to rip your throat out. It might be some cowpoke back in the corral.

The worst of it is that Jacob Tracy is not at all fond of his supernatural ability. He just wants to be a cowpoke and ride around on a horse and deliver Baptists to the Oregon territory. He distinctly dislikes the "vibes" when he gets into a place with too many unresolved dead folks. And he is deeply offended by the fact that this Fairweather woman recognises his psychic ability on their very first meeting.

Go to the full

review

The Guilty

Stories

Juan Villoro

Kimi Traube, Translator

(George Braziller)In these seven stories, Villoro tells the usual stuff of 21st Century life in the fast lane. A script for a movie that he is supposed to have written; getting a priest to baptise his Chevrolet on St. Christopher's day; an iguana that gets loose in it, eating the brake cables; a police officer who quotes Buñuel; the feng shui of his love Karla; helping border crossers in the desert with I. V. bags; working for a water company; a flight arriving too late to make its connection:The captain's voice has been replaced by landing music. We circle, miles above the ground, all of us watching the clock. How many flights will be missed on this flight? If the music were different we wouldn't worry as much. In some distant office, someone decided it was good to land to the beat of astral gypsies. And maybe it is. The discord of modernity and oranges. Music meant for arriving, not for waiting indefinitely with gates closing below.

Go to the full

reviewTram 83

Fiston Mwanza Mujila

Roland Glasser, translator

(Deep Vellum Publishing)Inadvertent musicians and elderly prostitutes and prestidigitators and Pentecostal preachers and students resembling mechanics and doctors conducting diagnoses in nightclubs and young journalists already retired and transvestites and second-foot shoe peddlers and porn film fans and highwaymen and pimps and disbarred lawyers and casual laborers and former transsexuals and polka dancers and pirates of the high seas and seekers of political asylum and organized fraudsters and archeologists and would-be bounty hunters and modern day adventurers and explorers searching for a lost civilization and human organ dealers and farmyard philosophers and hawkers of fresh water and hairdressers and shoeshine boys and repairers of spare parts and soldiers' widows and sex maniacs and lovers of romance novels and dissident rebels and brothers in Christ and druids and shamans and aphrodisiac vendors and scriveners and purveyors of real fake passports and gun-runners and porters and bric-a-brac traders and mining prospectors short on liquid assets and Siamese twins and Mamelukes and carjackers and colonial infantrymen and haruspices and counterfeiters and rape-starved soldiers and drinkers of adulterated milk and self-taught bakers and marabouts and mercenaries claiming to be one of Bob Denard's crew and inveterate alcoholics and diggers and militiamen proclaiming themselves 'masters of the world' and poseur politicians and child soldiers and Peace Corps activists gamely tackling a thousand nightmarish railroad construction projects or small-scale copper or manganese mining operations and baby-chicks and drug dealers and busgirls and pizza delivery guys and growth hormone merchants, all sorts of tribes overran Tram 83, in search of good times on the cheap."

That's just page 8.

The real genius of Mujila's picaresque novel --- it reads more like an epic poem --- is that, sure, it's about Africa and Africans, takes place in Africa, but it sums up and captures the intimate battle of darkness and desperation vs. hope and optimism that nearly every one of us fights within ourselves, in some form, at some point, maybe many times --- from the suburbs of the comfort-rich USA to the crumbling backwater hell holes of government-less nations largely ruled by regional war lords. It's a tightly focused story and a universal statement that seems to ask: Do you think there's a future or not, and if so, are you going to be there? That's the everyday query that fills Tram 83, the bar, and Tram 83, the novel, like thick smoke, then blows out into the streets --- and all around the world, and out into space, and beyond.

Go to the full

Go to the full

reviewEverything to Nothing

The Poetry of the Great War, Revolution,

And the Transformation of Europe

Geert Buelens

David McKay, Translator

(Verso)Buelen emphasises that poetry was not a distant, somewhat fey preoccupation of a small band of poetasters as in our own time, but was taken seriously, published everywhere as if it were news. Even the smaller daily newspapers devoted considerable space to verse. At the same time that 5,000,000 German and Russian troops were being mobilized, historians and anthologists (Julius Bab, Albert Verwey) tell us that during the summer of 1914, some 50,000 poems were being written in Germany about the potential for heroism on the battlefield. One writer claims that for all of August 1914 the number of poems published in the entire country may have been closer to 1,500,000.In early twentieth-century European culture, poetry was central to the educational system, and on special occasions newspaper often devoted prominent space to poetry.

"So the outbreak of mass versification at the start of the war was not really all that strange . . . The magnitude of the event made ordinary people wax lyrical." A typical paean from one Heinrich Lersch (a boilermaker!), went

Farewell all, farewell!

When we fall for you and for our future,

Let these words re-echo as our last salute:

Farewell all, farewell!

A free German knows no cold compulsion:

Germany must live even if we must die!§ § § Time was soon enough able to smother these rhapsodic voices. The war that all thought would be over and done with by Christmas managed to drag over into the next year, and then the year after that, and on into the years after that. Those who had written so heroically about the nobility of sacrifice became somewhat muted, and by 1918, there would be a new band of poetry and prose --- the likes of Fernando Pessoa (who wrote under a variety of names, including Alberto Caeiro) to imply that war/death/nobility might not be all that it was cracked up to be:

But war, more than everything, wants to alter and alter a lot

And alter quickly.

But war inflicts death.

And death is the Universe's disdain for us.Buelens cites the starkness of the rhythm of the daily death figures with the following math: "So that was the First World War: two hundred and fifty fresh corpses every sixty minutes, a Twin Tower every afternoon. On an average day, 900 French soldiers died, 1,300 Germans and 1,459 Russians. For the survivors, life on the front as typically tedious, anxiety-ridden and dirty." It also consumed time, turned its stalwarts old and wan. Wilfred Owen was to write in "Dulce et Decorum est,"Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.The less well-known Corporal Daan Boens was to write,

Vanish you moon! --- I long for night and darkness,

so that the world around me chars to coal forever

and the life within me dies --- no hope, and no distress,

I want the mighty windless void, sheer nothingness.

No no more rubble --- I myself am rubble . . .

Go to the full

reading