Norwood

Charles Portis

(Simon & Schuster)

It's Sunday evening in Petaluma, Calif., the former Egg Capital of the World, the current World's Wristwrestling Capital and the site of the World's Ugliest Dog Championship. I'm eating supper in a gas station that's been converted into a taqueria when in walks a big man wearing a black cap, black jeans and a black Harley-Davidson T-shirt. He is carrying a small child who's wearing pajamas decorated with pictures of dinosaurs. The jukebox is blasting mariachi music. The man twirls around several times on his boot heels with the happy child then comes to a stop in front of the cash register. I watch this bit of choreography then go back to my chimichanga, and to Norwood, Charles Portis' first novel.A gas station that's been converted into a taqueria is a perfect place to read Portis because it's the type of establishment in which his odd, funny, profoundly American characters frequently find themselves in most of his five novels: Norwood (1966), True Grit (1968), The Dog of the South (1979), Masters of Atlantis (1985) and Gringos (1991). They are the books that moved writer Ron Rosenbaum to crown him "perhaps the most original, indescribable sui generis talent overlooked by literary culture in America" and the country's "least known great novelist." (Rosenbaum's laudatory columns in the New York Observer and Esquire encouraged Overlook Press to put all of Portis' novels back in print.)

Of his five books, "True Grit" is the most well known and also something of an anomaly: It takes place in the old West. The tale's told by the female protagonist looking back from the early 1900s to events that occurred in the late 19th century. Portis' four other novels are set in the 20th century. In 1969 True Grit was made into a movie starring John Wayne, Kim Darby and Glen Campbell (and with Dennis Hopper and Robert Duvall in minor parts). Wayne won the Oscar for his role as a has-been lawman, the utter antithesis of every character he'd ever played before. But that's trivia.

What's rare, important and worth broadcasting about Portis' work is that it precisely captures the sound, feel and vernacular sensibility of certain parts of America (the Southern parts, mostly) and certain kinds of Americans (usually the Southern kind) better than any other fiction writer save Mark Twain, who, if he were around, would certainly be a fan. Portis is also one of the funniest goddamn writers on the planet. Walter Clemons, reviewing The Dog of the South in Newsweek said that reading Portis "is like being held down and tickled." I'd add that no one's going to need to hold you down - - - you'll find yourself begging for it. And that's the toughest part of getting a jones for Portis: He hasn't published a novel since 1991 and his last magazine article, "Combinations of Jacksons," a memoir, appeared in the Atlantic Monthly in 1999. But he's held in such high regard by other writers that even the Atlantic piece was reviewed in the Washington Post.

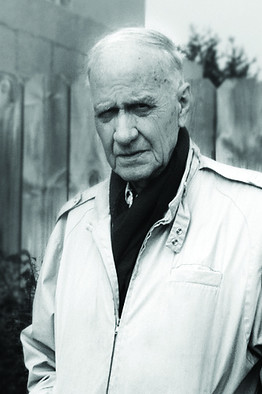

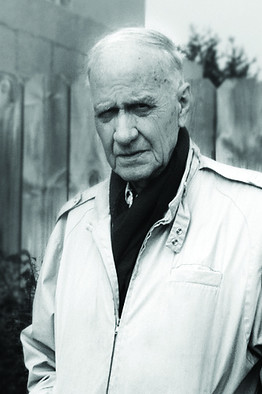

Portis, 68, a native of Arkansas, served as a Marine during the Korean War and worked as a journalist for a time afterward, including a stint as London bureau chief for the New York Herald-Tribune. He isn't funny in a jokey way; he's not a punch-line guy. The humor in his novels comes from the singular characters that populate them, and from his spot-on skill at putting the peculiar, the cranky or the off-kilter conversation on the page with a great deal of heart. The verisimilitude displayed in his dialogue makes you feel as if you've heard the same exchange yourself - - - or something very much like it - - - dozens of times. If you've bounced around the country some, you've heard, or had, these conversations in the backs of buses, in Holiday Inn lounges and late-night bar cars taking the train from, say, Memphis to Jackson, or in a Buick with a soldier boy hitchhiker making his way home to Port Arthur, Gallup or Spokane. If the Mad Tea Party were held at a diner just off the interstate with tuna melts and curly fries all around, that would be the sound of Portis' characters holding forth. Portis, like Whitman, hears America singing, but it's singing off-key and the chorus includes a chow dog that wears plastic bags on its feet, a college-educated chicken named Joann and Edmund B. Ratner, "the world's smallest perfect fat man" and the second shortest midget in show business.

Put down that bag of Fritos for half a sec, hit the cruise control, turn up the volume, roll down the window and listen. Here, from the opening chapter of Norwood, is Norwood Pratt's exchange with Mrs. Remley, who's traveling on a Trailways bus with her husband and baby, Hershel. The Remleys "had been picking asparagus in the Imperial Valley and were now on their way home with their asparagus money." Norwood strikes up a conversation by remarking on how well behaved young Hershel is.

Mrs. Remley patted Hershel on his tummy and said, "Say I'm not always this nice." Hershel grinned but said nothing.

"I believe the cat has got the boy's tongue," said Norwood.

"Say no he ain't," said Mrs. Remley. "Say I can talk aplenty when I want to, Mr. Man."

"Tell me what your name is," said Norwood. "What is your name?"

"Say Hershel. Say Hershel Remley is my name."

"How old are you, Hershel? Tell me how old you are."

"Say I'm two years old."

"Hold up this many fingers," said Norwood.

"He don't know about that," said Mrs. Remley. "But he can blow out a match."

If the use of "Mr. Man" in the fifth sentence - - - not to mention the "blow out a match" ending - - - makes you want to fly out to Arkansas, hunt down the reclusive Portis and take him out for a super-size cheeseburger just so you can hear one of the truest, funniest voices in contemporary fiction actually speak, then you've already joined the cult. Welcome. If not, my heart goes out to you - - - life has dealt you a cruel hand.

Most of the time in most places in this country, not much is going on. If you take a big dose of TV news you may think that there's one edge-of-your-seat, dramatic event after another unfolding across the land. If you take off and drive it, however, you'll find that the opposite is true. Most weeks, a horse getting loose on the highway or a pickup with an engine fire is any region's numero uno high drama event. And everywhere, people try to fill the gaps, drown the oppressive silence. They try to get things going, but they can't get started, things just don't work out - - - because they don't have enough money, or they don't have enough know-how or they haven't really thought through what it is they want to do or if there's any good reason to do it. Meanwhile, they've got to cope with runaway wives, broken-down cars, old friends who need loans, bad love, sick dogs, fast-talking hustlers and the various other obstacles and banal confusions that make up the fabric of American life. It's the fabric, too, of Portis' jocular, compelling fiction - - - you can't wait to find out what's not going to happen next.

In Norwood, - - - perhaps one of the most entertaining novels ever written, the plot, such as it is, has Norwood Pratt coming home from the military to Ralph, Texas, on a hardship discharge. His father is dead and there's no one else to look after Vernell, his sister, "a heavy, sleepy girl with bad posture." On the way home he meets the Remleys and invites them to stay the night at his home in Ralph. He gives the little family his father's bedroom and he sleeps on a cot in the kitchen. Vernell is "in bed sick with grief." In the middle of the night the Remleys leave, "taking with them a television set and a 16-gauge Ithaca featherweight and two towels." It's just the first of many disappointments for Norwood, a trusting soul if there ever was one, a tirelessly optimistic man who knows there's no good reason to be optimistic.

All he really wants is to find a girlfriend and sing on "the Louisiana Hayride." At one point he imagines himself backstage having a smoke with Lefty Frizell: "Hey Norwood, you got a light?" But instead he gets embroiled in the felonious schemes of Grady Fring, the Kredit King, while trying to collect $70 he loaned to a no-account Marine buddy. As in all of Portis' books, the characters are on the move, infected with that most American of viruses, the one that compels constant motion, that forces people to roll long distances across this country's endless landscape in search of something, but usually not the thing they think they're in search of. By the time Norwood's quest ends, he's actually found much of what he's after - - - through little fault of his own. And the reader is ready to start the trip all over again on that Trailways bus with the Remleys. - - - (Norwood was also made into a movie in 1970. It starred Glen Campbell, Joe Namath and Kim Darby. No more need be said about it.)

True Grit, Portis' odd duck (if such a thing is possible with this writer), is a conventional unconventional western. Again, Portis' finely tuned ear gives us exquisite dialogue spoken by characters that, in 1968, we simply hadn't come across before in cowboy fiction - - - multifaceted antiheroes. His one-eyed, tumble-down gunman, Rooster Cogburn, and the tough, single-minded 14-year-old girl, Mattie Ross, who employs Cogburn to track down the man who murdered her father, remain two of the most distinctive, memorable individuals in 20th-century fiction. And though the story has a more driving plot than Portis usually brings to his novels, it's the words he puts in Rooster and Mattie's mouths with such apparent ease that propel this tale.

I don't know of any contemporary writer, including Elmore Leonard, who hand-carves conversations that so accurately and playfully capture the picaresque, fluid nature of American colloquial speech. But what Portis does in True Grit is craft a stiff, formal way of speaking - - - there's not one contraction in the book's dialogue; it bears no resemblance to the speech in Norwood. It is perfectly suited to his 19th-century characters, Mattie and Rooster, their relationship to one another and their almost biblical mission: retribution, the righting of a wrong. Did people ever really speak this way? We can't be sure, but we can be certain that Mattie and Rooster did, at least in Mattie's memory as related in this "true account." In any case, it casts a spell over the reader, this spare, economical way of talking.

Mattie, whom Walker Percy likened to Huck Finn, is an old soul with the unwavering moral certainty of a child, while Rooster, a wreck of a U.S. marshal, seems just about played out. He understands the great grayness of life, but Mattie's ethics - - - and the cash she offers him to help her hunt down her father's murderer - - - are irresistible. The two have their first meeting after Rooster's given a less than glowing performance testifying in court about a criminal who should've ended up in his custody, but who instead he fatally shot. As Rooster exits the courthouse, Mattie makes her introduction:

I approached him and said, "Mr. Rooster Cogburn?"

He said, "What is it?" His mind was on something else.

I said, "I would like to talk with you a minute."

He said, "What do you want, girl? Speak up. It is suppertime."

As they speak, Rooster fumbles with a cigarette, trying to roll it with shaking hands. Mattie takes the papers and tobacco from him, rolls it, hands it back. Thus Portis gives us a gunfighter too feeble to roll a smoke, a lawman outclassed by a little girl. The two continue talking:

I said, "I am looking for the man who shot and killed my father, Frank Ross, in front of the Monarch boardinghouse. The man's name is Tom Chaney. They say he is over in the Indian Territory and I need somebody to go after him."

He said, "What is your name, girl? Where do you live?"

"My name is Mattie Ross," I replied. "We are located in Yell County near Dardanelle. My mother is at home looking after my sister Victoria and my brother Little Frank."

"You had best go to them," said he. "They will need some help with the churning."

There is some talk about the fee Mattie will pay Rooster, then he asks to look in her bag:

He said, "What have you got there in your poke?"

I opened the sugar sack and showed him.

"By God!" said he. "A Colt's dragoon! Why you are no bigger than a corn nubbin! What are you doing with that pistol?"

I said, "It belonged to my father. I intend to kill Tom Chaney with it if the law fails to do so."

And one of the great duos of modern fiction saddles up for a rough, bullet riddled 224-page ride.

After the relatively austere drama of True Grit, and the passage of 11 years, Portis returned to modern times with The Dog of the South, a road trip novel that takes us from Arkansas to British Honduras, traveling with 26-year-old Raymond E. Midge. Midge is hunting for his credit cards, his problematic wife, Norma, and his beloved Ford Torino, all of which have been appropriated by Norma's first husband, a surly ne'er-do-well named Guy Dupree who's written "abusive letters to the president, calling him a coward and a mangy rat with scabs on his ears."

Midge takes off after the two in the car Dupree left behind in Midge's parking space at the Rhino apartments, a '63 Buick Special "with a quarter-turn slack in the steering wheel." One of many little pleasures in Portis' books is the way he writes about cars - - - with the deep, greasy knowledge of a guy who's been up close and personal with his share of blown head gaskets, spun rod bearings and smoked pistons. Like a cowpoke dependent on a crippled horse, Portis' characters are saddled with no end of anxiety due to the marginal health of their vehicles. If you ever lost a carburetor return spring in the middle of Nebraska on a Sunday or blew a U-joint in Midland at midnight you'll empathize with one of the spiritual burdens Portis' people often carry.

In addition to the indefatigably stoic Ray Midge, The Dog of the South introduces us to Dr. Symes, a splendid and bigoted grouch who lost his license to practice medicine. Symes' live-in bus, named the Dog of the South, gives the novel its title even though it spends the entire story offstage, parked in the mud, crippled by a burnt wheel bearing. Midge, who sees it as his duty to help one and all, agrees to take on Symes as a passenger.

As they drive south, Midge slowly gains the doctor's trust, even though Symes doesn't approve of his driving, and learns a little about Symes' spotty past:

... he had been traveling in the shadows for several years. He had sold hi-lo shag carpet remnants and velvet paintings from the back of a truck in California. He had sold wide shoes by mail, shoes that must have been almost round, at widths up to EEEEEE. He had sold gladiola bulbs and vitamins for men and fat-melting pills and all purpose hooks and hail damaged pears. He had picked up small fees counseling veterans on how to fake chest pains so as to gain admission to V.A. hospitals and a free week in bed. He had sold ranchettes in Colorado and unregistered securities in Arkansas.

All purpose hooks! That's Portis writing in overdrive, pedal to the metal. We wouldn't have a more vivid portrait of Symes if it had been rendered by Vermeer himself. Later, Midge, whom the doctor has nicknamed Speed, says he'd like to visit California sometime. Symes tells him, "You'll love it if you like to see big buck niggers strutting around town kissing white women on the mouth and fondling their titties in public. They're running wild out there, Speed. They're water skiing out there now."

Water skiing, indeed. Portis doesn't insist that we like his characters; he makes them quirky, not cute. Still, we can't take our eyes off them. They're all fairly benign souls in the scheme of things, but rich in pettiness and with a propensity for irritability. Snappishness is epidemic in Portisland. What would a Mad Tea Party be without it? How could a circus of fools operate in its absence? Yet his characters are also sweet, needy, often falling apart and barely hanging on to society's raggedy fringes. They're innocents, both absurd and real.

As they usually do in Portis' books, things finally get tied up (or unraveled) in The Dog of the South, in messy fashion. And by the end we know that the story has gathered so much momentum that it, and its characters, will go on, even accelerate without us or Portis in attendance.

It's all but impossible to pick a best among his five books, but if novels are small, hand-hewn worlds, then perhaps none of Portis' is so all-enveloping, so fully fleshed out in its authentic loopiness as 1985's brilliant display of storytelling virtuosity, Masters of Atlantis. (Although some, as one reviewer put it, see the book as "one long slip on a big banana peel," I am not among them.)

Set in the early decades of the 20th century, Masters of Atlantis is the tale of "the Gnomon Society, the international fraternal order dedicated to preserving the arcane wisdom of the lost city of Atlantis." The Gnomons, the society's founders and members, are a handful of men - - - Lamar Jimmerson, Austin Popper, Sydney Hen and various other, equally earnest, clueless characters - - - whose fractious relationships and bottomless wells of credulity fuel the story.

Coincidentally, just a few months before I began rereading Portis' novels in preparation for writing this article, I reviewed two books for Salon.com: Drake's Fortune: The Fabulous True Story of The World's Greatest Confidence Man, a biography of Oscar Hartzell, and The Bizarre Careers of John R. Brinkley. Both are about American scam artists who hit their zenith in the 1920s and '30s, the golden era of the con. The crucial difference between real-life grifters Hartzell and Brinkley and Portis' fictional ones is that the men of the Gnomon Society have been most successful at conning themselves, they haven't a clue that Gnomonism is a load of hooey. They swear by their opaque, indecipherable sacred text, the "Codex Pappus," wear their conical hats, "pomas," with pride and reverence and otherwise view Gnomonism with the awe they're convinced it deserves. Its tenets are never quite pinned down - - - it is so deep it mustn't be explained or questioned - - - but that doesn't shake the belief of these endearing ninnies.

Portis perfectly nails the atmosphere, the need to believe in the easy answer, the craving for hope and the quick fortune, the shabby charisma of those who seem to possess a sort of vaporous certainty. And as usual his story is energized with wry, funny dialogue. In Richard Rayner's book on Oscar Hartzell, who made millions selling shares in the nonexistent estate of Sir Francis Drake, Rayner writes that Hartzell's urgent wires to his investors "fizzed with self-importance and conviction. He preached. He commanded. His tone of authority impelled his readers to believe that he was indeed dealing with the 'highest powers that be,' the 'King's and Lords' Commission,' and the 'Ecclesiastical Courts.'" Rayner could just as well be describing Portis' men in Masters of Atlantis, though they're the kind that Hartzell preyed on: believers not always adept at getting others to subscribe to their beliefs. Yet at one point Austin Popper does show a Hartzell-like flare for attracting converts:

There was no shortage of men on Lake Erie but the wisdom of Atlantis, clarified though it now was, still did not hold their attention. Popper had to grope about for ideas they could hearken to. Little by little he worked things out ... The Gnomic content of his lectures diminished daily as the Popper content swelled. Soon he had a coherent system, one with wide appeal, and he had to book ever-larger rooms and halls to accommodate the growing number of men who came to hear his words of hope.

For this was what he gave them. Through Gnomonic thought and practices they could become happy, and very likely rich, and not later but sooner. They could learn how to harness secret powers, tap hidden reserves, plug in to the Telluric Currents. It was all true enough.

As eccentrically entertaining as it is, Masters of Atlantis is also a trenchant send-up of belief systems (religious or otherwise), salesmanship and America's enthusiasm for merging the two.

Finally, dammit - - - at least until the next Portis novel shows up - - - comes Gringos, atmospheric as all get-out, whimsical, charming, lush with marginal characters - - - expatriates living in Yucatan, Mexico - - - and with American Jimmy Burns leading the parade of out-of-round yahoos, New Agers, UFO seekers and thugs. Burns, the writer tells us, was once described in a job reference, as "a pretty good sort of fellow with a mean streak. Hard worker. Solitary as a snake. Punctual. Mutters and mumbles. Trust-worthy. Facetious."

Yes, Burns is a somewhat different Portis protagonist - - - sharp, both cynical and amiable, though not an innocent in a guilty world like Norwood Pratt, the Gnomans, Raymond Midge or Mattie Ross. He's fully capable of sneaking up on you, which is exactly what Gringos does. Appropriate to its setting, it floats more or less forward at a leisurely, seemingly random pace while Portis' steady hand on the tiller allows us to lean back and enjoy the trip without obsessing about the destination. But make no mistake, there is one.

What becomes clear when you read all of Portis' novels in succession, as I have just done, is how important it is to the writer to change gears, to stretch his voice, to keep inventing fresh ways to observe his peculiar specimens and evoke the comic reality that Americans seem to take with them wherever they go - - - to accompany the dark reality that sometimes follows them like a homeless puppy with a bad case of mange.

Clumsy and good natured we are and, mostly, hardworking. Trustworthy? Sure, except for the ones who aren't. Mean streak? Sometimes, sorry to say. And we usually show up on time even if we are a bunch of rubes.

Through it all, lucky for us, we've got Charles Portis, god bless him, to keep us company while we're at the taqueria eating chimichangas.

--- Douglas Cruickshank