The Abundance

Essays Old and New

Annie Dillard

(Brilliance Audio)

Annie Dillard is all style. Whether she is talking about debris, or Teilhard de Chardin, or an eclipse of the sun - - - her words catch you, and you are gone.There is in Dillard a mystic if not holy air, the divine who is to be found in the most casual of places. At Pilgrim Creek, we find frogs that disappear before your eyes. On the beach, we find sand that did not come from the ocean's waves, nor from deserts. In a total eclipse of the sun, we find people screaming in terror. "Seeing a partial eclipse bears the same relation to seeing a total eclipse as kissing a man does to marrying him - - - or as flying in an airplane does to falling out of an airplane," she tells us.

Dillard's style is sometimes a breathless magic that (mostly) works, making a surprise of the simplest facts or visions. Simple things turn catastrophic.

"The mind wants to live forever, or to learn a very good reason why not." She quotes Wallace Stevens, "It can never be satisfied, never." And there again, there's that subtle presentment of the Dillardish divine: "The mind wants the world to return its love, or its awareness; the mind wants to know all the world, and all eternity, even god."

She thinks on that earlier catastrophist, Knut Hamsun, who said that he wrote "to kill time." Perhaps she does it too, for she has published nothing since 2007. These essays are selections from her previous twelve books. Perhaps she no longer has time to kill time.

She thinks that Hamsun's thought is "funny in a number of ways."

In a number of ways I kill myself laughing, looking out at islands [of Puget Sound]

Dillard uses pinpoint vision to see the world . . . and in the vision always finds an element of tragedy, if not terror. Thus, her visions are often emergencies, and "just around the corner there is always madness."

The hint of madness in meditation lies near as well: "The worlds spiritual geniuses seem to discover universally that the mind is a muddy river, this ceaseless flow of trivia and trash cannot be damned . . . trying to dam it is a waste of effort that might lead to madness." Even personal thought must not be tampered with . . . because if you do, you risk your sanity.

Part of Dillard's vision is so intimate that it transforms the eye - - - rather, her eye - - - into a microscope. She spends an inordinate amount of time in this book talking about dust (!) and sand (sand!) "The more nearly spherical is a grain of sand, the older it is."

"The average river requires a million years to move a grain of sand one hundred miles," James Trefil tells us.

Most of us believe that sand is manufactured by waves banging up on rocks, but this is not true. Sand always starts by rocks grinding up each other in rivers, and often ends up being blown to and about in deserts. "In the desert, it keeps itself round. Most of the round sand grains in the world, where ever you find them, have spent some part of their histories blowing around the desert." Sand moves enormous distances to get to the ocean, where it can fall like rain and be collected by the waves to end up at water's edge.

§ § § A few of these essays are from her first successful book, A Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. "She scrutinizes nature with monastic patience and a microscopic eye," one reviewer wrote. "She delivers doctrine with the certainty of revelation and the arrogance (and agedness) of youth. She summons us to wake from dull routine. With flourishes of brass, she proclaims a new dawn . . . In a curious way, she is absent from her own book."

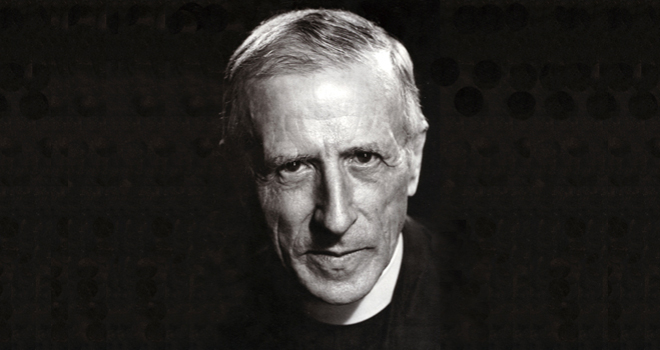

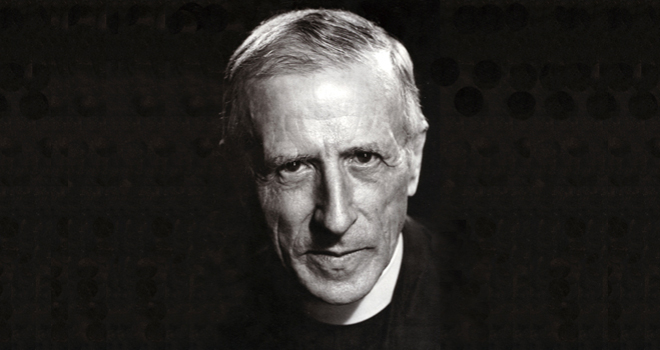

There's an endearing paean to Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. "We live surrounded by ideas and objects infinitely more ancient than we imagine," Teilhard said, "and yet at the same time everything is in motion." Teilhard becomes the notional saint of The Abundance. Dillard seems sincerely stricken by his martyrdom, in that he was a Jesuit who was kept as far from Rome as possible for most of his life.

Each year, he requested that the church permit him to publish his various geological and philosophical tracts. "Every year, he applied to publish his works; every year, Rome refused." The church let him visit France briefly when he was sixty-five. And when he was seventy-three, dying of heart disease in New York, Rome forbade his publishing, lecturing or returning to France. In a letter to a friend, Dillard reports, he raged, but said that he stuck with Catholicism "because it is the only hope we have."

With one exception, he was refused permission to publish . . . indeed, when he was new to the church, he was sent to a special earthly purgatory in the far off areas of China. He spent twenty-two years studying one of the most deserted, barren places on earth --- the Gobi Desert. And his studies there were fruitful. By digging deep into the sand beneath his feet, and with great effort, he was able to come up with the ruins of a civilization, the ancient civilization of the Pekin Man.

His friends begged him to abandon his chosen religion, but he refused. Why? "The Catholic Church," he wrote late in life, "is still our best hope for a path to God, for the transformation of man, and for making evolution meaningful It is "the only international organization that works."

Rarely, and privately, he did complain: "The sin of Rome, " he wrote to a friend, "is not to believe in a future . . . I know it because I have stifled for fifty years in the sub-human atmosphere." He concluded, "Yet all that is really worthwhile is action," for

"Personal success or personal satisfaction are not worth another thought."

§ § § Most of all, what we have with Annie Dillard is style. She can shape words like love for a brilliant Jesuit, or implying the madness induced by a daytime's complete absence of sun, or a frog being imploded on Tinker Creek. Her art is to take visions and transforming them into words we can love, even visions that you or I may not even see. "You must allow the muddy river to flow unheeded in the dim channels of consciousness," she says.

The reading here is by Susan Ericksen. She reads slowly, with a readerly up-and-down voice, like your third grade teacher reciting Winnie the Pooh. But Dillard's prose calls for - - - no, demands - - - more of what we would call a natural style, a conversational . . . even a flat reading. For Dillard's writing is all conversation, a brilliant friend bending your ear.

On this disc, the editors have included a forward to the book by Geoff Dyer. He wants to tell us how good Dillard is. As fond as we are of Dyer, this may be appropriate for the published volume, but for the disc that we may have already bought, it's an unnecessary waste of our time.