A Kind of Dream

Kelly Cherry

(Terrace)

Sometimes we reviewers get stuck. I don't mean writer's block. No, I mean when we have a book and we are stuck somewhere like an airport, flights delayed, not sure when we'll arrive where we think we want to be, finding yourself stuck with a book that we picked willy-nilly from the review stack.So I got stuck at Newark. Newark! Better Indira Gandhi Flyway in Delhi, I guess. Or Soekarno-Hatta International where ever that may be. Anyway --- all I plucked off the top of the pile before departure was Kelly Cherry and her kind of dream.

I found that she had published over thirty titles before, after, or during this one, including instruction books on poetry and "a meditative autobiography." She writes and writes and writes . . . unstoppable, maybe. A Kind of Dream consists of ten interlinked stories.

It's a little drab starting out. Our five or six main characters are listed formally, English-lit bio style, with a little history. It's like notes for a text-book of an English major but there can also be a touch of drama as we wander through their tales.

Take Babette Bryant --- better known as BB --- who takes off for Hollywood with Roy, leaving behind her just-born baby Tavy who is then raised (and loved) by her loving aunt Nina. Like our author, Nina is a writer who frets about writing ("Was it foolish of Nina to use her own name in her story? Norman Mailer had used his.")

In one story, BB, now a lovely movie actress, goes off with Roy --- he's the director --- to Mongolia to make a film there on the steppes where she meets a tall Japanese named Takeo who asks her "Do you fry a plane?" which I guess she likes because maybe they will have an affair. He has long fingers and when they go to see the waterfalls at Orkhon Khurkhree he says "Water is so chirry" (this means "chilly") and when he puts on his bathing suit there are "square shoulders, six-pack-abs, those long legs" and in the ger it looks like we'll get a Japanese - American entrepôt . . . we're all stripped down, I'm ready, he is too . . . but she finally says no.

Why?

Because he insists on wearing a condom.

Eh?

Takeo is as puzzled by this odd refusal as are (presumably) Cherry's readers. Especially this one --- never really finding condoms, although not very salubrious, as being all that opprobrious. Takeo finally, and wisely, says: "It's your husband's responsibility."

Note that the author does not have him say "responsibirity."

§ § § These stories which have their ups and downs, go on at length about the responsibilities of being a writer and how one should not be abandoning one's children --- they even, in one case, get pissy, like when BB comes back, twenty-five years after the fact, to see the daughter Tavy that she gave away. When Tavy asks how come Roy didn't tag along BB says he's editing a film and so she says "Or he wants you to give him a report before he gets mixed up in this" and when BB says he didn't know, and "I don't even know how he'll feel about my having seen you," Tavy says, "You don't know much."

Message: don't dump your kids on your aunt then show up a quarter-century later expecting a warm and loving reception.

What these ten stories do not have is all that much coherence. For instance, in the middle of the set there on page 89 we find a two-page aside on babies, which tells us that "A baby always arrives on its birthday" and "You may smell the baby. It has a delightful baby smell as long as its diaper is not full" and this rather fetching thought:

The ears of babies need stimulation. If you want your baby to be happy all its life, set it down in the middle of a string quartet. Let the baby crawl around the violinists' and the violists' feet . . . The music will soak into the baby; it will hear that music in its mind always. Even when the baby is grown up and sad, that music will play in its mind and the baby will smile."

The other thing that these stories lack is something we mordant types always look for in our reading . . . something in the trade known as wit or humor. Give us a few knee-slappers to keep us going. Although we may have a chapter here called "Faith Hope and Clarity" . . . this is more in the punning department which we sardonics could use a little less of, frankly.

It's all very serious and life can be serious here what with the death of a premature child, a mass shooting in the library when we were having a children's reading knocking off Aileen the librarian who we had already gotten rather fond of. And, yes, there is the normal loneliness of widows and widowers (and writers, god knows) for life can be bleak . . .

. . .but for some of us, all we ask are just a few jollies, if you can. To keep our interest if not our dander up.

But then here is a surprise: a bonus. One that comes right at the end of the book, one that is so good that it sets us to wondering why Ms. Cherry can't have been more cheery all along, cram in a few more boffs in her stories as we are going along on the narrative not just waiting until we get to the dead end, there overlooking the yellow-smoking ash-heaps.

I mean, Christ, Kelly. You're thirty books into this stuff and we have to wait until page 155 (out of 159) for this great dog named Virgil to come and take over our tale, bring the whole sputtering machine to life.

Picture it. Nina is dying and is sad because she wants to keep on writing and so she starts thinking of the words she always wanted to use in her books and now won't be able to so do. Like, Oilily. "He winked at her and asked oilily if she'd go out with him." Or Wackadoodle. "The guy was wackadoodle. Or should that be a wackadoodle?

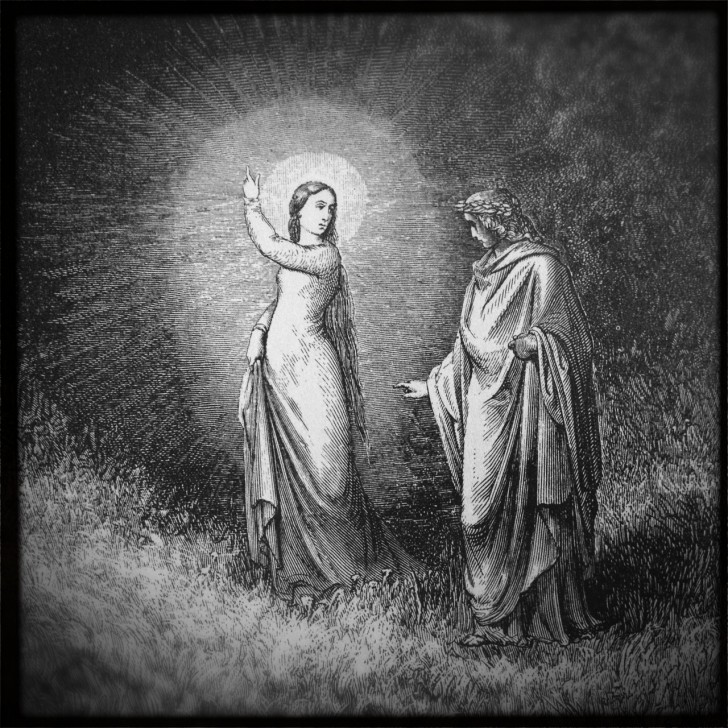

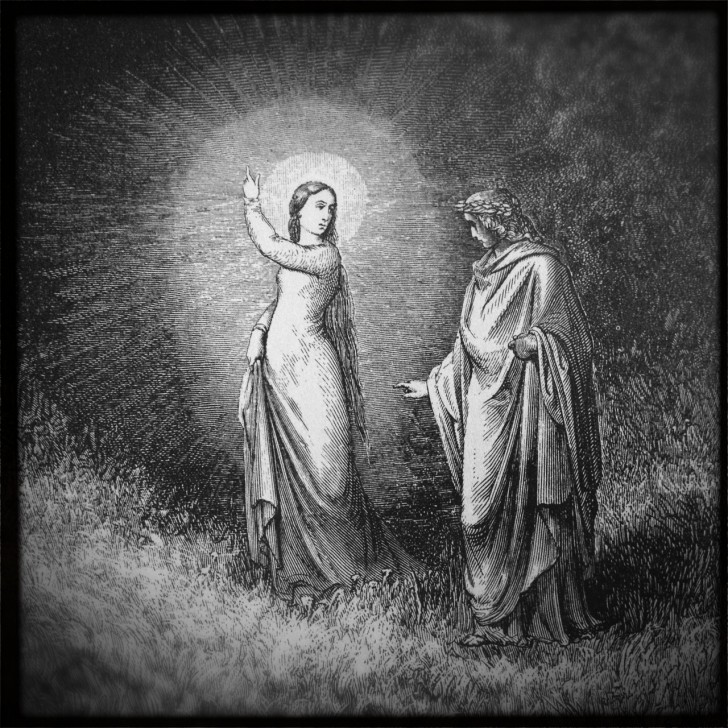

So in the midst of all this, as Nina begins to fade, and since we all start to fade as we drift away and old friends and family those from long ago and far away begin to pop up . . . and suddenly here's mom and dad and, yes, Virgil the pup, assigned by those in charge to lead her, presumably, through the whole of the Divine Comedy that, they say, makes up the terminal part of all of our lives.

--- Am I just imagining all of you?

--- Why do you say "just imagining," Nina? her father asked. I always through you took imagination seriously.

Virgil nipped at her ankles as if to say, if you could call me up with your imagination, wouldn't you have done so long before now?

--- Oh, Virgil, I would have.

--- I'm glad you're finally using my name.

--- It's such a heavy name for a little dog. I don't know why I burdened you with it. I regretted it right after I filled out your AKC papers . . .

Virgil barked. His sturdy little salt and pepper body, his jaunty tail gladdened Nina's heart.

--- What is it? Nina asked.

--- We have to keep going, Virgil said . . .

--- Over there, Virgil said, pointing with his whole body as if he had ferreted a rat from its hiding place.

Nina turned in that direction, expecting --- what was she expecting? She had no idea. Perhaps --- a sentence, a sentence that would sum up everything that needed to be said.

What she saw was not a sentence, not a brilliant fire burning words onto the black screen of outer space.

--- Do you see? Virgil asked.

She did. She saw, and what she saw was good and beautiful and true, but it was too late to tell anyone.

--- Pamela Wylie