From Patriots to Victims

David M. Rosen

(Rutgers University Press)

"Without doubt there are many circumstances where the recruitment of children has been criminal and cruel by any standard. The cases of Joseph Kony and the Lord's Resistance Army as well as that of Sierra Leone's Revolutionary United Front easily come to mind." But, writes David Rosen,over the centuries many children --- heroes, villains, patriots and victims --- have been child soldiers. Joan of Arc, Carl von Clausewitz, Andrew Jackson, Moshe Dayan, Yasser Arafat, Ishmael Beah, and even Dr. Ruth Westheimer were child soldiers.

"Their stories cannot be reduced to simple formulas of abuse and exploitation. This book is a partial attempt to show how history, culture, and circumstance shape our understanding of their participation in war." A case in point is The American Revolutionary War.

The American Revolutionary War lasted eight years, from 1775 to 1783. It was, to all intents and purposes, a civil war, one fought by the Patriots (or Whigs, those fighting to make the United States independent of England) against the Loyalists (or Tories, those who wanted to remain part of the British Empire). British soldiers joined the Loyalists, were called "the regulars." Just to confuse things further, France, Spain and the Netherlands joined the melee, and we can call them "the allies," since they joined the Whigs.

"During the war," writes Rosen, "the armies, militias, and partisan groups of both sides were filled with children." In one study by Steven Mintz, it is claimed that "between 30 and 40 percent of adolescent males participated in armed conflict between 1740 and 1781." Records show that the First to Eight Connecticut regiments, for example, 179 of 655 soldiers (27.3 percent) were between ages twelve to seventeen.

Of the 922 soldiers of the Pennsylvania Line of the Continental Army between 1775 and 1783, 113 (12 percent) were ten to seventeen. . . . The vast majority of young soldiers across the militias and regiments of the revolutionary forces were fifteen, sixteen or seventeen years old. Many of the youngest were fifers and drummers, but many were also ordinary private soldiers.

Before the 20th Century, by necessity the young were seen as dispensable. The mortality rate among children born before 1900 could be close fifty percent: that is, only half could be expected to live to see their tenth birthday in what we call the Eurocentric world. Of the twenty-three children born to Johann Sebastian Bach, for instance, only ten reached full adulthood.Children who managed to survive were assumed to be miniature grown-ups, non-verbal adults merely without the capacities of older people. By the time war and revolution came around, the boys routinely joined their fathers or older brothers to pick up a gun or a machete or a pitch-fork to protect their honor, their family property, their country.

Some of those who emerged as heroes were fourteen-, fifteen-, or sixteen-years old. For example, Andrew Jackson saw his first combat when he was thirteen. In 1780, the regulars from England descended on the Carolinas. In the Battle of Waxhaws, in which Jackson participated, one witness, a doctor by the name of Brownfield, reported: "there was indiscriminate carnage never surpassed by the most ruthless atrocities of the most barbarous savages." Since Jackson's brother had been killed by the regulars, he and another brother embarked on a plan to "kill the fighting men, and thereby avenge the slaying of partisans."

The Civil War was little better. A recent study of the U. S. Natoinal Archives tells us that of a sample of over 35,000 soldiers, medical histories show that around twenty percent "were recruited into the Union ranks between the ages of nine and seventeen." By extrapolation, almost 420,000 of the total military force of 2,100,000 were what we now refer to as "underage." And this is a conservative figure. A career military analyst, one Charles King, estimated, in 1911, that the figure would be closer to "800,000 below the age of seventeen, 200,000 were under sixteen, and another 200,000 were no more than fifteen."

The author of Child Soldiers assumes that the figures for the Confederate states would be very similar, notes that even these figures may be artificially low. The urge to fight to protect family, friends, and entitlements encouraged younger men to lie about their ages and, in any event, usually, such was the need for cannon-fodder, their declared ages were accepted as true. The rate of mortality for both Southern and Northern armies was between 750,000 - 800,000 deaths: the war managed to kill off at least 160,000 American children.

One former boy soldier, John Lincoln Clem, stated that "boys were good for the army" and that the training and experience were valuable for them. "Most importantly, he argued that of all soldiers they had the highest degree of élan because of their ambition, skill, endurance, fearlessness, and willingness to obey order."

"War," he wrote, "is bald, naked savagery. Disguise the fact though we may try, it properly bears that definition. As compared with the adult man, the boy is near to the savage.

World War I is found to be not all that dissimilar. Although English army regulations specified a minimum age of eighteen, "during the first two years of the war, volunteerism was the norm and the army was filled with boy soldiers, as boys from all over the country sought to enlist in violation of army regulations. Scant attention was paid to any serious method of determining age. The army, hungry for soldiers, was a reluctant enforcer of its own regulations." A Punch cartoon shows an officer interviewing an obviously underage candidate, and asking "Do you know where boys go who tell lies?" The boy answers, "To the front, sir."

Victor Silvester, later a famous British orchestra leader, "enlisted in November 1914. He was fourteen years and nine months old. When asked his age, he said eighteen and nine months. He was examined by the medical officer, determined fit, and quickly sworn in. He returned home to inform his patents."

During the course of the war, some 8.7 million individuals served and 956,703 died from wounds, injury, or disease. By conservative estimates some 250,000 soldiers were underage, and about 55 percent of these were killed or wounded during the war.

§ § § Then there is the 20th Century phenomena known as Total War. The Nazis killed over 1,500,000 Jewish children in the Holocaust. In addition , a systematic murder of children came about through the introduction of V-1 and V-2 bombings of England, the Japanese annihaliation of cities in China, the indiscriminate bombing of German cities 1943 - 1945, the fire bombing of almost 100 Japanese cities during the same period, and the ultimate atomic bombings of Nagasaki and Hiroshima. Common estimate of civilian deaths during WWII "due to military actions and crimes against humanity" numbers approximately 28,000,000, and "deaths due to war related famine and disease" another 28,000,000 - 30,000,000. With the commonly accepted figure of 20 - 25% of these being children under the age of eighteen, approximately 13,000,000 - 14,000,000 children died between 1941 and 1945 through the aegis of adult wartime activities.

The thrust of Rosen's excellent, in-depth (and superbly written) study is to note the change between then and now. He sees some of it as a new vision of war "as a criminal enterprise." Thus, what was acceptable even a hundred-and-fifty years ago is now seen as a brutal violation of the childhood. This is reflected in the so-called "laws of war" that criminalize the recruiting or using of children under the age of fifteen in direct combat.

There are exceptions. During the Iran-Iraq war, Iran brought in 95,000 children "above age twelve, some as young as nine, to be used as human waves to clear areas of land mines." Currently, the U. N. reports that there are seven nations that recruit child soldiers, those under eighteen years of age: Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Myanmar (Burma), Somalia, Sudan, South Sudan and Yemen. "A decade ago," states Rosen, "much attention was focused on conflicts in Africa south of the Sahara, but as even as some of these conflicts have waned, recruitment is now spreading across the Middle East, North Africa, the Horn of Africa, and the Sahel."

He concludes the book with the thought that although we have created peace (mostly) in the west, "we have, understandably and luckily, lost our visceral understanding of war." Even so, during the war in Iraq, it was the United States, Great Britain, and their allies who killed thousands of civilians --- not only men and women but, too, children.

Obviously, there is nothing new about warfare or hypocrisy, but in recent years all these processes of distancing, demonizing, sanitizing and "othering" have transformed us into distant observers, ultimate noncombatants, with little firsthand knowledge of the kind of warfare that often thrusts children into combat in their homelands.

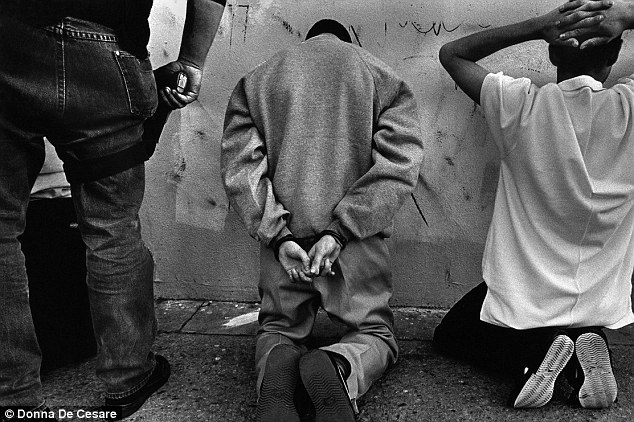

One element of child soldiery not emphasized by the author are the conflicts now raging in American cities, where children, known as "gangs" --- well-armed by fiat of American law ("the right to bear arms") --- are engaged in a civil war that has been raging for decades. The law of our country prevents the military from accepting anyone under the age of eighteen from being on active duty, so the underage are left to battle it out on the home territories.

John Clem declared that children between the ages of ten and seventeen are perfect for the paramilitary warfare," the very hostilities that dominate our inner cities. "As compared with the adult man, the boy is near to the savage," he wrote.

We find the drafting of "child soldiers" in Africa scandalous, yet ghetto warriors are a guerilla force scarcely hidden from the public eye. We can wring our hands over juveniles in the Congo or Liberia carrying AK-47s, enlisted by hardened rebels to fight in blood-lust inter-tribal wars. But we have a multitude of child-soldiers in our own center cities, sometimes drafted for battle because they are so young they cannot be prosecuted under laws affecting their elders.

Linda L. Dahlberg, the associate director for science in CDC's Division of Violence Prevention, notes that the gun murder rate is highest among male children and teens. According to the CDC, 25,423 murders by gunfire took place in the United States in a typical recent year. The rate of firearm homicides was higher in inner cities than in other parts of cities and higher than the murder rate of the country as a whole, Dahlberg said. "Children and teens aged 10 to 19 in these areas --- more than 85% of them male --- accounted for 73% of all firearm homicide," she writes.

A review of data compiled by the Children's Defense Fund documented that between 1979 and 2009, 116,385 children died due to gun violence in the United States. Extrapolating from recent numbers, by the end of 2015, Americans have allowed over 134,000 children to die from gun violence; 47 percent of these children were African American. And, according to Marcos Crespo in City & State Magazine (March 2016):

More recent data tells us that over 28,000 children and teens were killed by guns between 2003 and 2014. "In the two-year period from 2008 to 2009, 34,000 children and teens were injured by guns. This translates into one child injured by a gun every 31 minutes of those two years, equal to filling 1,375 classrooms of 25 students each. Today, one teen per hour is hospitalized due to gun violence in the United States."

Thus this war of child soldiers is not some distant tragedy. It is happening at this moment in a city near you.

--- Carlos Amantea