On the evening of 3 October 2013, a boat carrying more than five hundred Eritreans and Somalis foundered just off the tiny island of Lampedusa. In the darkness, locals mistook their desperate cries for the sound of seagulls. The boat sank within minutes, but survivors were in the water for five hours, some of them clinging to the bodies of their dead companions as floats. Many of the 368 people who drowned never made it off the capsizing boat. Among the 108 people trapped inside the bow was an Eritrean woman, thought to be about twenty years old, who had given birth as she drowned. Her waters had broken in the water. Rescue divers found the dead infant, still attached by the umbilical cord, in her leggings. The longest journey is also the shortest journey.Already, in the womb, our brains are laying down neural pathways that will determine how we perceive the world and our place in it. Cognitive mapping is the way we mobilise a definition of who we are, and borders are the way we protect this definition. All borders --- the lines and symbols on a map, the fretwork of walls and fences on the ground, and the often complex enmeshments by which we organise our lives --- are explanations of identity. We construct borders, literally and figuratively, to fortify our sense of who we are; and we cross them in search of who we might become. They are philosophies of space, credibility contests, latitudes of neurosis, signatures to the social contract, soothing containments, scars.

They're also death zones, portals to the underworld, where explanations of identity are foreclosed. The boat that sank half a mile from Lampedusa had entered Italian territorial waters, crossing the imaginary line drawn in the sea --- the impossible line, if you think about it. It had gained the common European border, only to encounter its own vanishing point, the point at which its human cargo simply dropped off the map. Ne plus ultra, nothing lies beyond.

I have no theory, no grand narrative to explain why so many people are clambering into their own hearses before they are actually dead. I don't understand the mechanisms by which globalisation, with all its hype of mobility and the collapse of distance and terrain, has instead delivered a world of barricades and partition, in which entire populations seem to be living --- and dying --- in a different history from mine. All I know is that a woman who believed in the future drowned while giving birth, and we have no idea who she was. And it's this, her lack of known identity, which places us, who are fat with it, in direct if hopelessly unequal relationship to her.

Everyone reading this has a verified self, an identity, formed through and confirmed by identification, that is attested to be "true." You can't function in the world without it: you can't open a bank account, get a credit card or national insurance number, or a driving licence, or access to your email and social media accounts, or a passport or visa, or points on your reward card. You can't have your tonsils removed without it. You can't die without it. Whether you're conscious of it or not, whether you like it or not, the verified self is the governing calculus of your life, the spectrum on which you, as an individual, are plotted from cradle to grave. As Pierre-Joseph Proudhon explained, you must be "noted, registered, enumerated, accounted for, stamped, measured, classified, audited, patented, licensed, authorised, endorsed, reprimanded, prevented, reformed, rectified and corrected, in every operation, every transaction, every movement."

Proudhon, who wrote this in 1851, was the first person to style himself an "anarchist," so naturally he blamed the state for everything. And this makes his jeremiad insufficient for today (as I suspect it was in his time), because it presents us as passive victims of this overdetermined onslaught of verification, rather than hyperactive participants. We are, as Terry Eagleton put it in the LRB (1 June 2000), "a fanatically voluntaristic society," obsessed with public self-exposure and suspicious of "reticence or obliquity." But we all have what Milan Kundera calls the "epidermal instinct to defend one's personal life." Never mind the front door, back door, garage door, car door (and the petrol cap), or the safe, or the desk drawer containing your life insurance policy, just think of how many other locks you use, every day, all day: on your computer, your phone, Facebook, Amazon, bank account, credit card --- all those memorable dates and memorable digits and memorable passwords and memorable answers to memorable questions that we store in some special key room inside our brain.

But then think about the vast amount of detailed personal information we release into the atmosphere, all the time. You can't see it, but there's an endless belch of digital exhaust coming out of the smartphone in your pocket. If you've got an Apple watch, or a Fitbit bracelet, it's coming off your wrist. Even when idle, these devices are sending and receiving hundreds of thousands of communications to and from servers across the globe, independently of you, but using your identity. It's not identity theft, because you've consented to it by dint of the numberless pages of small print you've neglected to read. Your identity is being trafficked and traded, with your permission, by interested parties about whom you know nothing. If any of your devices has geolocation technology, and you haven't turned it off, you're now transmitting your exact location to God knows who or what, silently bip-bip-bipping like a little sputnik.

If you use a registered Oyster card to make journeys in London they will be tracked through a microchip embedded in the card, a tiny electronic system known as RFID, or Radio Frequency Identification, which contains your data in the form of a unique code that signals who you are, how much credit you have, the number of the credit card you used to pay for it. This chip has a miniature antenna which, when activated, sends and receives information to and from an external database, via the reader in the gate. You don't actually need the card at all, it's just a convenient casing for the chip. Once the reader confirms your identity, the separation barrier opens to let you through --- another border crossed, another layer of identity fat acquired.

These integrated chips or circuits are everywhere, the invisible key of all identity verification. There's one in your credit card, in your car key, your phone, your work ID and entry card, your passport. If you're a criminal out on licence, or a registered asylum-seeker outside a detention centre, or a newborn baby in some hospitals, there's one in your ankle tag. If you're a dog, there's one between your shoulders. Human microchip implants are not yet widely available, but l found a web-based company called, with admirable frankness, Dangerous Things, which sells a 'sterile injection assembly' kit, currently reduced from $67 to $39. This kit enables you to push a chip, encased in 'borosilicate biocompatible glass,' through your skin --- the epidermal border --- and once lodged there it will engage in a lively conversation with your computer or other smart devices and do all sorts of things for you, like open the car door or turn the heating on or tell your doctor you're having a heart attack. Implantable GPS-enabled chips are still theoretical, but could make it possible for a person to be located anywhere in the world by latitude, longitude, altitude, speed and direction of movement. Useful if you've been kidnapped in the Western Sahara, or you're lost in the car park at Westfield shopping centre. Useful, too, if you're tracking migrants.

Identity is established by identification, and identification is established by documenting and fixing the socially significant and codifiable information that confirms who you are. This process is called biometrics, literally 'life measurement,' and its purpose is to reformulate identity as collectable, readable, exploitable data. In other words, you are a database from which some sort of content is extracted or 'captured,' then algorithmically encrypted and stored for retrieval in a much larger database. Biometrics include personal information, behavioural traits, and unique physiological characteristics such as DNA, blood group, fingerprints, facial geometry, iris features, dorsal vein patterns.

In Proudhon's day, the manufactories of the verified self were still paper-based --- and it's worth noting that it was the mass production of paper in the 15th century that revolutionised the keeping of records. It's a case of function following form: just as, later, the skyscraper followed the invention of the elevator, so the great chancelleries of the world were built on paper. Today, although we're still afflicted by endless paper forms, the constant production and maintenance of biometric data is principally driven by smart technologies of the sort I've been describing.

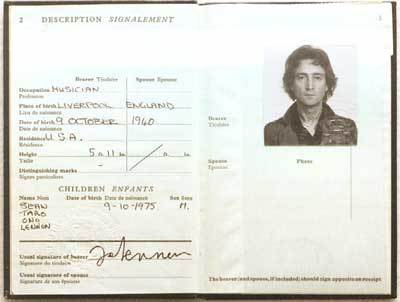

The fulcrum of the digitally verified self is the electronic passport. Most of the time, my UK passport won't transmit data because it has no power source of its own, but it wakes up when it enters the electromagnetic field of the reader installed in smart border control systems. Once it's powered up, the chip identifies itself by sending a 'unique identifier' to the reader, and when this is accepted, it transmits its content using a digital signature to confirm the authenticity of that data. It's a double-lock system, designed to prevent your electronic identity being stolen and cloned by hackers. Currently, the data on my chip are the same as on the front inside page of the passport: first name, family name, date of birth, sex, nationality, document serial number, issuing state, expiry date --- a coupling of me with the authority of the state that confirms this is me. The e-passport also contains a digital copy of the photograph I submitted along with my original application.

The passport photo is the court with no appeal, the one 'likeness' guaranteed to show you looking the way you never want to look. Paul Fussell called it 'the most egregious little modernism,' redolent of 'the world of Prufrock and Joseph K and Malone,' and indeed every time my photo is scrutinised by a passport officer, it's as if I've entered that same world of anxiety and disassociation. As Stefan Zweig put it, I cease to feel as if I quite belong to myself. I split off from my bureaucratic double, and then the passport officer waves me through and I lurch at the insult --- you really believe that's me?

They know it's me. The digital copy of my photograph in the microchip is a IPEG that can be enlarged to a far higher definition than the little cut-out on the passport. This means that my unique facial geometry can be read by Automated Facial Identification software that traces the precise distance between my eyes, nose, mouth and ears. This is the reason we're not allowed to smile when we sit for the photograph. Smiling was banned in 2004 along with frowning or raising eyebrows because this software treats the face as a blank somatic surface, scraped clean --- exfoliated --- of all affective expression, in order to be differentiated from other faces. It's a search for fixed markers, not a full cartographic survey.

--- Frances Stonor Saunders

The London Review of Books

3 March 2016