In 1866, Mark Twain spent four months in Hawaii, then known as the Sandwich Islands, on assignment for California's Sacramento Union newspaper. He'd agreed to write a series of letters during the trip, which was his first outside the United States. The Union published 25 of them.Twain had not yet written a book in 1866, but just four months before his trip to the islands he'd placed himself in the national consciousness with the appearance of "Jim Smiley and His Jumping Frog" in New York's Saturday Press. The piece was reprinted widely in U.S. newspapers.

I first began to grasp the extraordinary nature of Twain's experiences in Hawaii about thirty years ago, when I was staying in a rural corner of the Big Island. I owned three jungle-covered acres there on which I was planning to build a small house. (When friends on the mainland asked me what the property was like, I'd say "Imagine a painting by Henri Rousseau done on a three-acre canvas.") I went back and forth between San Francisco and the islands every few months. Sometimes I'd stay for a week; sometimes I'd stay much longer. While there, I lived at a friend's vacation home that had no electricity; the nights were illuminated by the moon, candles and kerosene lamps. The rain swept in across the sea from the south and poured down in drops the size of coffee beans. The evenings' entertainment was reading, with a hot sake chaser; the soundtrack was the nearby ocean sharply slapping the black cliffs.

It was during those nights that I discovered and rediscovered Mark Twain's work and also immersed myself in books about him. I reread many of his novels and collections of journalism, and I read Letters From Hawaii for the first time. And the second time. And the third. I developed a fascination, some say an obsession, with Twain's travels in Hawaii, and how the experience changed him, recharged and redirected his career; and how the place became not merely a fond memory for him but also an enduring symbol, a touchstone.

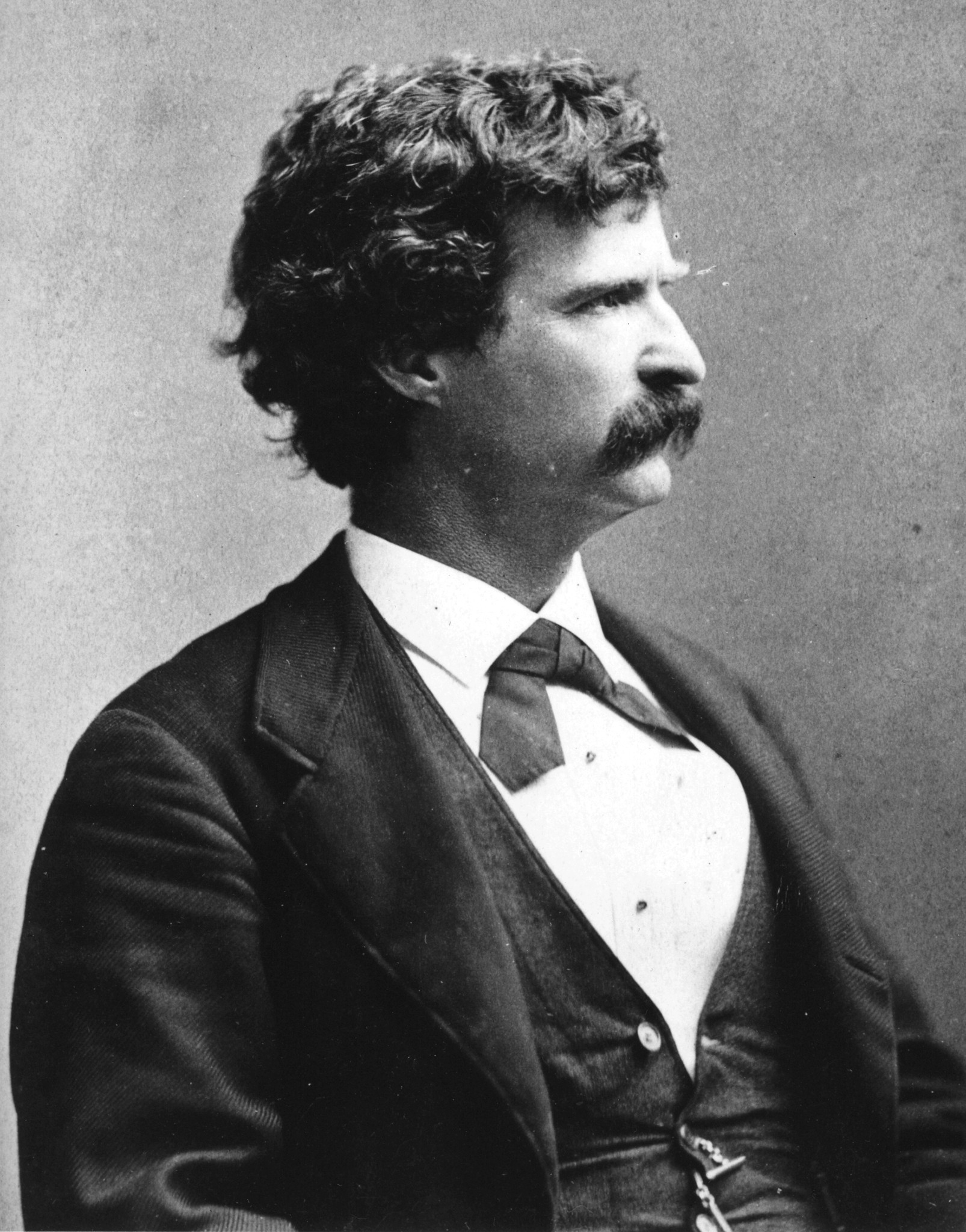

When he went to the islands at the age of 30, Twain was coming out of a "lost weekend" period that had lasted a year or more. It was a time in which his talent was evident and his brilliance obvious, but meaningful success had been elusive. He had only been using his pen-name for about three years when he went to the islands, and his emergence as a novelist, humorist and lecturer of international reputation was still ahead of him. He was based in San Francisco in the period leading up to the trip and was known --- inasmuch as he was known at all --- as a promising, if inconsistent, regional writer. His future was not at all certain.

Indeed, less than two years earlier he'd been quietly let go by the city's Morning Call newspaper ("I retired from my position on the Morning Call, by solicitation. Solicitation of the proprietor," he wrote in his autobiography). He had become nearly destitute, had been a fugitive from the San Francisco police, had considered suicide and at one point was arrested for public drunkenness. In his classic biography, Mr. Clemens and Mark Twain, Justin Kaplan compared the writer's early trajectory to that of another American original: "The life of Ulysses Grant, like Mark Twain's," Kaplan wrote, "had been a saga of the unpredictable and the unlikely, of a man without promise who, after years of drift, failure, alcoholism, and disgrace, was touched by history and the Holy Ghost and achieved greatness." By 1866, Twain was ripe for change, ready to touch history, and Hawaii and its ghosts were ready to work a spell on him.

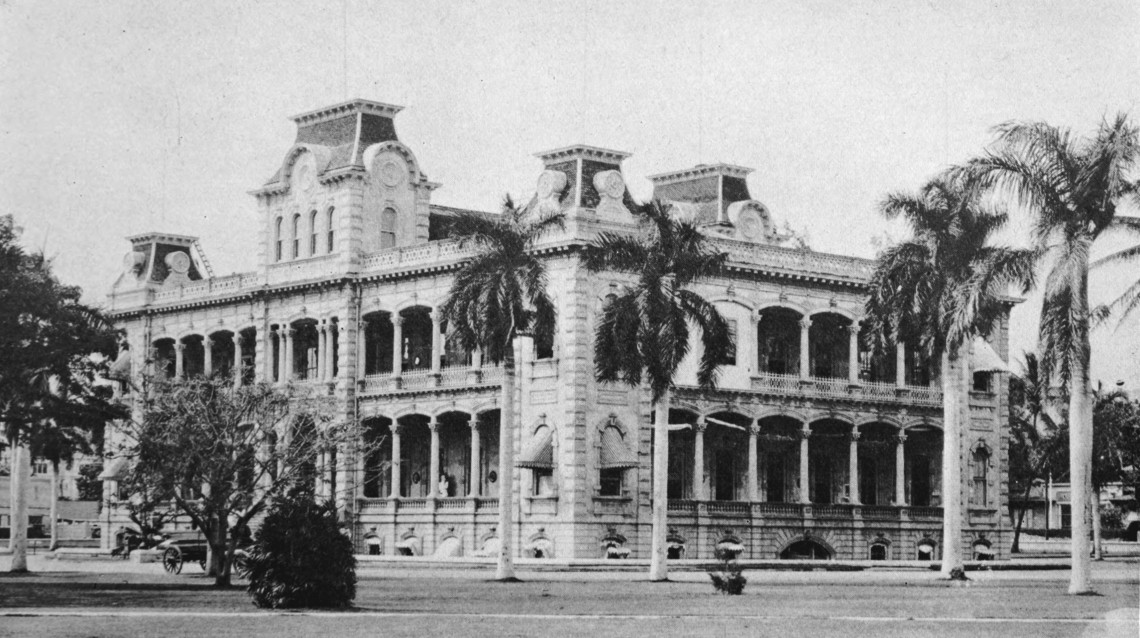

Upon arrival in the islands, Twain found a kingdom in transition, a societal microcosm, a model world, a planet Hawaii, where native innocence, rampant colonialism and the religions of two distinctly different worlds had cross pollinated to create a strange hybrid culture. If being in such a place at such a time hotly focused Twain's thinking about human nature, religion and one society's ability to transform another (and not necessarily in a good way), it's hardly surprising; it would be surprising if it hadn't affected him this way. As late as 1884, eighteen years after visiting the Sandwich Islands, Twain, in a letter to a friend, described a story he was planning that would be set in Hawaii: "Its hidden motive will illustrate a but-little considered fact in human nature; that the religious folly you are born in you will die in, no matter what apparently reasonabler religious folly may seem to have taken its place meanwhile, and abolished and obliterated it." (He never completed the story as he'd originally conceived it. He changed the setting to medieval England, and the Sandwich Islands parable became A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court.)

In 1889, more than two decades after he'd last set foot on the islands, Twain rhapsodized about the place in a speech: "No alien land in all the earth has any deep, strong charm for me but that one; no other land could so longingly and so beseechingly haunt me, sleeping and waking, through half a lifetime, as that one has done. Other things leave me, but it abides; other things change, but it remains the same. For me its balmy airs are always blowing, its summer seas flashing in the sun; the pulsing of its surf is in my ear; I can see its garlanded crags, its leaping cascades, its plumy palms drowsing by the shore, its remote summits floating like islands above the cloud-rack; I can feel the spirit of its woody solitudes, I hear the plashing of the brooks; in my nostrils still lives the breath of flowers that perished twenty years ago."

The funny, fact-filled reports Twain wrote for the Sacramento newspaper were enthusiastically received by a mainland readership hungry for information about the exotic kingdom at a time when American interest in Hawaii was on the rise; whaling was dying out, but the lucrative sugar industry was burgeoning. Coming on the heels of his popular jumping frog story, the Hawaii pieces gave Twain's reputation momentum by establishing him as a travel writer with a scintillating wit. In so doing they laid the groundwork for his first major book, The Innocents Abroad (1869), which would make him rich and famous.

After coming back from Hawaii, success didn't knock at Twain's door --- it kicked it down. "I returned to California to find myself about the best-known honest man on the Pacific coast," Twain said, and the editors of his three volume Notebooks & Journals wrote, "The year 1866 was a watershed in Mark Twain's career."

But why? What was it about Hawaii that got so far under Twain's skin? Why, 23 years after his only visit there, after he'd traveled the entire world, did he say "no other land could so longingly and so beseechingly haunt me?" Nearly two decades after his return he wrote to his friend William Dean Howells, "My billiard table is stacked up with books relating to the Sandwich Islands: the walls are upholstered with scraps of paper penciled with notes drawn from them. I have saturated myself with knowledge of that unimaginably beautiful land and that most strange and fascinating people."He may not have consciously absorbed everything that Hawaii symbolized to him when he was there --- its commercially and militarily strategic location, its sociopolitical dynamics and its almost erotically appealing natural world --- but on some intuitive level, and certainly from the vantage point of age, Twain understood the depth and gravity of the enormous changes taking place in Hawaii and how they were a portent for the changes that would come to the world at large. In the islands, Twain saw the best and worst of America, and of humanity, in microcosm.

The overarching themes and preoccupations that surfaced in Twain's work throughout his long career resonate with the social, political, commercial and religious forces at play in Hawaii in 1866. Said Kaplan, "All the 'accidents' of Mark Twain's life had some kind of purposive meaning --- so it seemed to him in his old age, when he tried to map out the turning points by which he had become a writer." Twain was an author, Kaplan observed, "whose creative unconscious lies closer to the surface than it does with most men, and whose life, consequently, is full of psychologically loaded accidents and coincidence." It seems certain that the change in direction Twain took in the Sandwich Islands was one of the most significant "psychologically loaded accidents" of his life.

Twain had a passion for Hawaii that never let go of him and that gained momentum as he aged. Like recalling a first love, his feelings about what he termed "the loveliest fleet of islands that lies anchored in any ocean" intensified throughout his life, and Hawaii in recollection became even more Edenic than he had found it. Twain seemed to see the place as almost mythological, iconic. As a fellow Twain aficionado once put it to me when we were discussing the writer's stay in the islands: "Did he invent paradise, or did it invent him?" The answer is neither and both, but the question suggests the intriguing possibility that something happened to Mark Twain in Hawaii. Something, or a series of things, evoked an intense catharsis --- perhaps intellectual, perhaps emotional, perhaps spiritual, and maybe all three.

What did Hawaii mean to Twain, not only while he was there but also over the span of his life? Did he see it as a metaphor for the world itself, for heaven and hell, for good versus evil? His observations about the missionaries, the Hawaiian natives, social dynamics, politics, paganism and the role of the church in transforming Hawaiian culture all seem to indicate a man already --- at 30 --- deeply preoccupied with profound questions, but always with an entertaining digression close at hand.Twain the journalist-trickster succeeded in his Hawaiian reports at being simultaneously jocular and trenchantly insightful. "How sad it is," he wrote, "to think of the multitudes who have gone to their graves in this beautiful island and never knew there was a hell." A performer on the page as well as on the stage, Twain understood how to seduce an audience; we are hooked by his humor from the very first sentences of his first letter from Hawaii:

We arrived here today at noon, [he wrote,] and while I spent an hour or so talking, the other passengers exhausted all the lodging accommodations of Honolulu.... There are a good many mosquitoes around tonight and they are rather troublesome; but it is a source of unalloyed satisfaction to me to know that the two million I sat down on a minute ago will never sing again.

Yet the innovator that essayist Gary Kamiya has called "the funniest major writer in the history of world literature" didn't merely make humorous prose using American colloquial speech, he pioneered the idea of journalism written in the style of fiction while making himself the protagonist (and employing fictional characters when it suited him; in the Sandwich Islands pieces it's "Mr. Brown"). In his letters from Hawaii and subsequent travel narratives, the transcendent wiseacre anticipated Gonzo journalism a century before the New Journalists came on the scene. (Biographer Ron Powers has called Twain and his colorful Virginia City cohorts "proto-psychedelic.")

The multi-faceted Twain was also a romantic --- Kaplan deemed him an "expatriate from his own times" --- who deified the past. "All of his major books were to be tales of yesterday..." Kaplan wrote, "through the rest of his career as a writer he turned further and further back into yesterdays...." Twain, Kaplan contended, "felt himself swept under by 'infinite great deeps of pathos,' by waves of helpless longing for a lost Eden...." For Twain, going to the Sandwich Islands may have been like traveling backwards in time to a tropical Arcadia. Twain's voice as a writer was still developing when he wrote the Sacramento Union letters. This is evident from the inconsistency of their style --- sometimes unreservedly wacky, other times ploddingly expository. In this period he gathered his confidence, reimagining himself and his work. Hawaii, with its primeval landscape, dreamy climate and rich stew of natives, pioneers and scalawags had a powerful impact on the young writer. Hawaii showed him the ways in which travel to exotic places could transform his work.

Perhaps, as different as Honolulu was from his cherished boyhood home of Hannibal, many of the island city's qualities reminded Twain of the Missouri town where he'd grown up, and from which he would draw inspiration all his life. In fact, discounting the dramatic differences in their surrounding landscape and climate, the two ports vaguely resembled each other. Honolulu, with its exquisite mix of innocence and rowdiness, a place where Twain could both lose himself and find himself, with its waterfront and the gentle slope of its streets rolling down to the harbor, can be seen as a tropical Hannibal, a parallel city that, like Hannibal, accelerated his creativity. By going to Honolulu, Twain journeyed to the past and found his future.

Whether or not Twain's long trip to Hawaii was a conscious effort to reinvent himself, that was unquestionably one result of the months he spent there. His experiences in the Sandwich Islands, the wry, lucid reportage he sent the Sacramento Union and the lucrative lecture career he began when he came back to California marked a pivot point in his life. Clearly, his months in the islands were a catharsis for the writer: Twain before Hawaii and Twain after Hawaii were markedly different individuals. He left San Francisco as a journalist and returned as a performer who also happened to possess one of literature's most intelligent, funny and distinctive voices.