My artistic friends constantly complain that they are being ignored, that they work like hell, send stuff off, wait and wait --- and that nothing gets published. They say that they feel that they and their art have been abandoned in contemporary America, that they are victims of bad taste, bad luck, or worse, bad national aesthetic judgment.

My artistic friends constantly complain that they are being ignored, that they work like hell, send stuff off, wait and wait --- and that nothing gets published. They say that they feel that they and their art have been abandoned in contemporary America, that they are victims of bad taste, bad luck, or worse, bad national aesthetic judgment.But just think if they were writing in Russia less than a century ago. Not only would their poems or plays or concertos or movies get noticed, they would be scrutinised, carefully --- and if they veered off the path of the politically acceptable, they would be taken away, tortured, and either sent to the gulag or, more likely, shot. Their crime? Something vague . . . called "formalism."

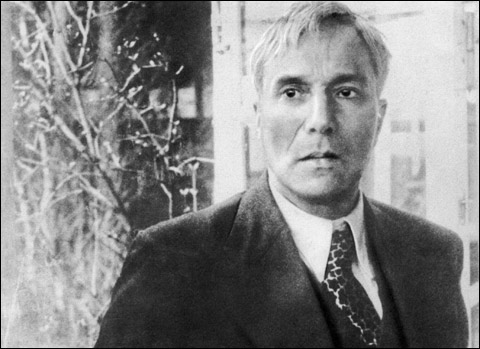

Such happened to Alexander Blok, Nikolai Klyeuf, Isaac Babel, Nikolai Gumilev ("the Russian Rudyard Kipling"), and the great Osip Mandelstam.

In 1933, Mandelstam wrote a poem about Josef Stalin which was not a very nice poem. It was one which would have gotten him scant attention in the rest of the world but in Russia, become very dangerous. No matter how funny it was to others, one was not to mock the Secretary of the Communist Party . . . the one who sat atop the power pyramid in the Kremlin.

His fat slug fingers as dirty plates

Words exact as leaden weights.

His cockroach whiskers beam

his tall boots gleam.Doesn't sound all that bad . . . except for the fact that everyone knew that it was about you-know-who and that Mandelstam had the foolishness to mouth it all around Moscow. When he tried to recite it to his friend Boris Pasternak, the latter shushed him up, said he shouldn't even be thinking such things, much less broadcasting it around town. Too late.

When brought in and questioned by the state police, the NKVD, Mandelstam said, "In 1930 a great depression afflicted my political outlook and my sense of ease in society. The social undercurrent of this depression was the liquidation of the kulaks as a class." Here he was talking about Stalin's direct order concerning the farming peasants of the Ukraine. He stated that since they were plutocrats, the national government had the right to take their livestock, their harvest, their seed-grain . . . and destroy their livelihood. And them.

This sudden assertion of state power, known as the collectivisation of the kulaks, began in 1929 and continued until 1940. It caused, it is estimated, the death of well over 5,000,000 Ukrainians. (It is said that at the Tehran Conference in 1943, Winston Churchill had the temerity to ask Stalin how many he had murdered in the collectivisation; Stalin held up both hands, palm outwards, fingers extended. Some said that he was just telling Churchill to shut up, but Churchill read it as "ten," i.e. 10,000,000 dead. He may not have been far from the truth.)

Mandelstam paid heavily for his satire of Stalin. He was sent to the gulag in the Magadan region, and in late 1938, he was to die of overwork and exposure. Never have so few words caused so much pain and suffering --- not only to the poet, but to members of his family who were penalised as well; and the rest of us, who lost the poetical works of a talented writer. But despite it all, he was a man of good cheer. He told Anna Akhmatova when she visited him in 1933 that "poetry is power" and

Why complain? Poetry is respected only in this country --- people are killed for it. There's no place where more people are killed for it.

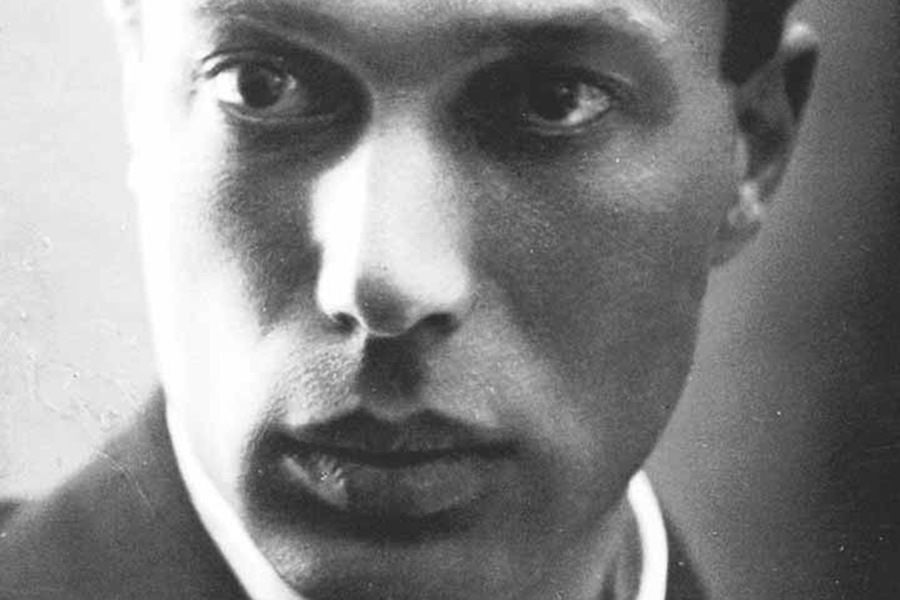

The one writer who comes out as truly heroic here is Anna Akhmatova, whose work was banned in 1925 and --- after the seige of Leningrad, where so many perished of starvation or sickness --- was assumed by many to have died. One of the most moving passages in Fear and the Muse involves Isaiah Berlin. He was a visiting don from Oxford who, when he arrived in Leningrad at the end of the war, asked if there were any writers still lived there, and was told about Akhmatova. "Is she still alive," Berlin asked, surprised.He was given her address, and arranged to meet her that afternoon. "The person who greeted them was not the charismatic poet whose angular features were immortalised in a 1914 oil painting by Nathan Altman but a stately gray-haired lady with a white shawl across her shoulders, a noble head, an unhurried manner, and a face that expressed a lifetime of suffering."

When Berlin met her, "Her manner was so regal and severe that he bowed to her, as if she were a monarch." Their conversation --- which lasted most of the night --- was recorded, in detail, by Berlin. At one point, she spoke lines of her own, including her unfinished "Poem Without a Hero," and, Berlin recalled, "I realised I was listening to a work of genius." She also read Requiem from a manuscript, "breaking off to talk about the years 1937 - 1938 and the queues outside the prisons." As punishment for her, Stalin had seen to it that her son, Lev, was imprisoned in Leningrad, and ultimately shipped off to the gulag at Norilsk, "the most northern human settlement in the world."

And when Berlin asked her about Mandelstam, "a long tear-filled silence followed until she begged him to change the subject."

The man who arrived unexpectedly from a country where people speak their minds freely, who brought news of friends she had not seen or heard from in a quarter of a century, was the last great love of Akhmatova's life. On the manuscript of her "Poem Without a Hero," she wrote a third and final dedication to the "Guest from the Future," an obvious reference that was considered so dangerous that the Soviet editors of her posthumous collected works reluctantly left it out. He is probably also the person she was referring to in these lines written in 1956:

He will not be a beloved husband to me

But what we accomplish, he and I,

Will disturb the Twentieth Century.The question at the heart of Fear and the Muse is offered up to us in the last chapter: "Why this appalling regime was host to such an extraordinary range of creative talent"

There were stable democratic states that allowed their citizens fully free self-expression but could not produce one artist of the stature of a Shostakovich, a Bulgakov, an Akhmatova, or a Pasternak. A disproportionate amount of the great art of the twentieth century came from a regime where to think freely was to risk death. The question this raises is, Why did they persist? Why would Osip Mandelstam spend his life composing poems he could recite only to trusted friends, without any prospect of getting them published? Why did Shostakovich not simply give up composing after the trauma of the suppression of his first opera?

Those of us who have the freedom to write or compose or film almost anything we want cannot conceive of a government with the power to murder writers or musicians or film-makers it considers politically incorrect. Why would they continue on under such pressure? Perhaps the secret is that those who are willing to persist in the face of such state-induced madness are going to have to have a touch of madness themselves.

This book gives us stark pictures of these who were tortured by the need to continue their art. And some, like Shostakovitch), had their bags packed and waiting on the stairs so that when the NKVD put in its appearance, they could be disappeared without waking the family. This spirit of persistence all while awaiting the final visit may be the key: "I create because I have to; it may kill me, but I have no choice." Or as Shostakovich wrote, "Even if they cut off both my hands and I have to hold the pen in my teeth, I shall go on writing music."

Fear and the Muse is a book that creates tension not only because McSmith is an artful writer, but because of the historical tension built into the story. The knowledge is that those five "greasy fingers" could, at any moment, order in the secret police --- after which the novelist, the musician, or the poet becomes toast. And another part of the fascination comes from the way that the man in the Kremlin could, at his discretion, play with you. At his own pace.

Mikhail Bulgakov wrote a masterpiece --- a novel which we now know as The Master and Margarita. He knew it would never be published in Soviet Russia, so he kept it under wraps. Meanwhile, many of his plays were staged but one of them, A Cabal of Hypocrites (also known as Molière), offered a delicious scene in which the 18th Century French playwright is invited to dine with Louis XIV.

Molière: No one in France, sire, has had dinner with you before. I am overwhelmed, and therefore somewhat nervous.

Louis: France, Monsieur de Molière, is sitting before you. France is eating chicken, and is not nervous.

Molière: Sire, you are the only person in the world who can say that!

Anyone with bat-brains knew that the 18th Century king here was in reality the 20th Century tyrant. And Bulgakov paid the price for his play. "He endured endless harassment from the authorities, until everything he wrote was banned except the one play that had received Stalin's personal endorsement."

McSmith claims that the reason that Stalin didn't just up and have all of them shot, the lot of them --- Eisenstein, Bulgakov, Shostakovich, Akhmatova, Pasternak (and several dozen other slightly rebellious writers and journalists and musicians) --- was because the General Secretary was no 20th Century Genghis Khan "from the bandit country beyond the Caucasus Mountains." Stalin was "indeed as ruthless and suspicious as any barbarian despot, but he was not ignorant. He had been educated at the Tiflis Seminary in Georgia, one of the best schools in the empire outside the major Russian cities."

Once in power, he was shrewd enough to understand that his regime gained in prestige from artists producing work that was genuinely admired at home and abroad. He was also clever enough to differentiate between real artists and hacks turning out rubbish to please the authorities. He would, when it suited him, arbitrarily raise a mediocrity like the now-forgotten composer Ivan Dzerzhinsky to sudden prominence while having his officials bully and harass Shostakovich, but his subsequent behaviour makes it obvious that he knew which of those two composers was a great artist and which was the mediocrity.

--- Pamela Wylie