Articles from Our Last Two Decades

Every 24 hours our server offers us

a report on the number of hits

we receive in any given day.

We are often intrigued enough to go

through these listings from

1996, or 2001, or 2008 or last year . . .

reviews of titles that we ourselves

gave to the world, but have all but forgotten,

despite being the literary midwife, so to speak.

Here are a dozen or so of those

which turned up recently,

permitting us to rediscover

them and bring back

many a fond memory.Into the Night

Tales of Nocturnal

Wildlife Expeditions

Rick A. Adams,

Editor

(University Press of Colorado)It's called Into the Night, but perhaps it would be better titled Scientific Lunatics Abroad Studying Packrats, Fruitbats, and Walking Batfish.You may recall that centuries ago people's futures were foretold by eviscerating a chicken and reading the gizzards. Here we travel all the way to Africa to study bat-poop --- not to look into the future, but to understand the present. Frank Bonaccorso's assignment has to do with a recent lack of figs in the countryside near the Shingwedzi River water basin in South Africa. He tracks down fruitbats and a sycamore --- a fig-tree sycamore. There should be figs on it, no?

However, during times of meteorological uproar --- read global warming --- the figs and even the fig-trees disappear, and the question becomes what's going to happen to the many animals dependent on it. Since fruitbats are expert disseminators of the seed of the syconium, are they doing their jobs by eating the figs, spreading their poop (and fig seeds) all about Kruger National Park? And are the other animals coöperating?

For instance, are fig seedlings being trampled to death by lions, leopards, African buffalo, rhinos, or the "120,000 impala, 30,000 zebra, or 13,000 elephants, or various other grazers and browsers?" How can we make sure that enough new fruiting sycamores appear so that all the animals survive? Thus Bonaccorso's research involving the "Walberg's" and "Peter's" bats of this area.

Go to the full

reviewA Woman's Work

With Gurdjieff, Ramana Maharshi,

Krishnamurti, Anandamaya Ma & Pak Subuh:

The Spiritual Life Journey of Ethel Merston

Mary Ellen Korman

(Arete) Ethel Merston was one of those insufferable not to say indefatigable English women who set out early on to have a Meaningful Spiritual Experience and ended up meeting with the five gurus listed in what must be one of the longest book titles in all of spiritualdom.

Ethel Merston was one of those insufferable not to say indefatigable English women who set out early on to have a Meaningful Spiritual Experience and ended up meeting with the five gurus listed in what must be one of the longest book titles in all of spiritualdom.Merston, born in 1883, lived damn near forever, and visited, studied with, and --- we might say --- collected all these famous masters as well as a host of other celebrities, including Gertrude Stein, Ruth Benedict, Hemingway, Brancusi, Lipschitz, Joyce, Ghandi, and both of the Cayces. She doesn't mention becoming a familiar of Jesus, but we assume that may lie further on in the book. We wouldn't know for sure, because we got lost there somewhere between Bhagavan Maharishi and Krishnamurti, just south of the Arunachalesvara Temple in Tiruvannamalai.

One thing that Merston was good at doing was exasperating the bejesus out of the various mystics she scared up. Only Gurdjieff seemed to know how to handle her, she being the product of the agonized, stuffy English upper class. She and Gurdjieff were at his Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man, in France, and he told her that she was in charge of the cows. Huh? She didn't know squat about cows, but there she was, at five in the morning, milking two large bossies and giving them feed.

Another time he said to her. "You grow rice." Ethel being Ethel complained that rice would not grow there in Prieure, but said, "If you really want me to sow rice, I don't care, I'll sow it, but it will just be a waste of money, for it won't come up."

She might have sewed a batch of basmati, but she didn't figure out what Gurdjieff was telling her even though she stayed on five years, showing an amazing obstinacy. It was said that Gurdjieff delighted in torturing his French devotees by demanding that they stick to a diet of red burgundy and bacon. We don't find out in A Woman's Work if Ethel participated in this sacrilege, but since she was from England, she probably didn't care all that much.

Go to the full

review52 McGs.

The Best Obituaries from Legendary

New York Times Writer

Robert McG. Thomas Jr.

<Chris Calhoun, Editor

(Scribner)The writing of obituaries is a serious business --- certainly not the place for wit, jovial remarks, or cynicism. At least, that is the canon. However, during his four-year tenure at the New York Times Obit Desk, Robert McG. [McGill] Thomas turned all this on its head. His mini-biographies were salty and pungent, showing but a modicum of respect for the newly fallen. At least, that is what we are led to believe from the "Forward" to 52 McGs (so titled because there are fifty-two obits --- called McGs. by their fans).It is apparent from a close reading that they are not obituaries at all, but, instead, fantasy pieces. We are guessing that they were somehow put over on the editors of that august institution because no one bothered to check Thomas' astounding and mostly unbelievable facts. Such as,

- In the obit for Marshall Berger, a "dialectologist," it is claimed that 33rd Street becomes "Toidy-toid Street" in Brooklyn because of the influence of the accents of upper class Southern ladies from New Orleans and Charleston;

- That the "memoirist" Philip O'Connor once jumped out from behind a door and shouted "Boo!" at T. S. Eliot;

- That duckpins, a ridiculous faux bowling game originating in Baltimore, could not be listed as the Maryland state game because the state's official sport is jousting;

- That Emil Sitka of Three Stooges fame (he was the straight man) named his two daughters "Eelonka" and "Little-Star" and his four sons "Rudigor," "Storm," "Darrow," and "Saxon." (Next they'll tell us that Saxon moved to the Angles area of England, to be called Anglo-Saxon);

- That Howard C. Fox created the zoot suit, complete with "reet pleat, the reave sleeve, the ripe stripe, the stuff cuff, and the drape shape;"

- That Thomas himself --- according to an obituary written by Michael T. Kaufman --- had a tendency, in his newspaper writing, "to carry things like sentences, paragraphs, ideas and enthusiasms further than at least some editors preferred."

Go to the full

reviewMongrels, Bastards, Orphans,

and Vagabonds

Mexican Immigration and

The Future of Race in America

Gregory Rodriguez

(Vintage)Spain's conquest of Mexico was not a matter of Marx, nor the ecclesiastical powers of the Catholic Church, but a foretaste of Jacques Casanova ... long before his time. The conquistadores had an interest in gold, and silver, and manpower --- but apparently they were most interested in sex.It is well reflected in the language. In what they called "New Spain," the word was "coger." In Iberia it meant "to get." In Mexico --- still --- it means "to screw." Whatever name you put on it, for the indigenous people, it meant having the women used, and used badly. It also reflected on the invaders. "The colony's high level of miscegenation challenged not only the labor system but also the Spaniards' very claim to authority ... Peninsular Spaniards already looked down on the [criollos], partly because many of the latter had some Indian ancestry."

Widespread miscegenation "led those at the top of society ... to cling to the concept of racial purity in order to maintain their position of power and authority in society."

For the Indians, too, it all was a matter of life and death ... because of the sicknesses the Spaniards brought with them. "The navigational advances of the Renaissance," says the author, "had unified the disease pools of Europe, Africa, and Asia and unwittingly imported all to America."

Before the conquest, central Mexico, roughly the size of France, may have had a population as high as 25 million ... By 1600, a mere 1-1/2 million survived.

"The demographic disaster that took place [throughout the Americas] after 1492 is probably without counterpart in the history of mankind."

Go to the full

reviewFamily Reunion:

Poems about Parenting

Grown Children

<Sondra Zeidenstein, Editor

(Chicory Blue)If you are planning to have any children in the next twenty-five years ... don't. Unless you are looking forward to fifty years (or more) in which you get to deal with alcoholism, anorexia, sullenness, blame (you!), sickness, lack of appreciation, inability to communicate, self-destructive behavior, late-night telephone calls, crying jags, grandchildren with life-threatening illnesses, and endless money-begs.She wants to hang herself from the rafters, she says

to me at the top of the stairs...Those are the opening lines of Joan Swift's poem "Ties," while Cortney Davis tells us about being in the airport café:How's work? I'll ask my son, trying to catch up.

He'll concentrate on his plate. I'll pick up the bill.Raymond Carver reports, "Oh, son, in those days I wanted you dead/a hundred --- no a thousand --- different times." And his daughter?You're a beautiful drunk, daughter.

But you're a drunk. I can't say you're breaking

my heart. I don't have a heart when it comes

to this booze thing.Pearl Garrett Crayton tells us to be very careful, "Please, please, please, please, please/don't step on my daughter's toes!" Why? She'll

cut you down to size,

scratch your eyes out,

pull out your hair,

go for your jugular vein,

flay you skinless,

trample you in the dust.By comparison: "I've seen cancers cause less misery."

Penelope Scambly Schott tells of the telephone call, and "the spooked nickering of my grown daughter/across three thousand miles of dark,/that iron shoe in my heart," while Sheila Gardiner explains that her daughter's "What will I do with the rest of my life?" ("dissolving my heart") comes "from years of paralysis."

And just so we'll know that this stuff reaches across ages, Judith Arcana interviews Jocasta in hell, asks how come she gave up her son. She says Laius bullied her into doing it, but mostly she was "crying over my loose belly, still soaked in milk." Besides, "He was king." Besides, who was to know, who in god's name could ever know,

When you look down at them in their baskets, wrapped in soft cloth, when they root for the nipple under your gown, pursing their tiny budlipped mouths toward the smell of you, their eyes still fogged, still changing.

"How could I have recognized him?" she wails, as every mother must wail when she looks into the eyes of her newborn and has no idea, no idea in god's great world that the babe in arms may someday rise up to smite the old man, strike him dead, then bury himself in the arms of the widow, the one who could not, not in a thousand thousand years, guess that this lovely young man, "my mysterious suitor, the supposed savior of my city" is, in truth the soon to be her blind --- blinded by his own hand --- son, that one-time "nuzzling, budlipped babe" of her own womb, now returned to her womb. In another direction, in another guise.

Go to the full

reviewFriendly

Fallout 1953

Ann Ronald

(University of Nevada Press)We've always been amazed by the way those in power can turn a threat into a thrill through the not-so-subtle use of propaganda, images, and mere words.For example, up until the middle of the last century, international manslaughter was mostly left in the hands of the United States Department of War. But in 1949, it was decided that it would be better to call it "The United States Department of Defense." Thus, the war in Afghanistan comes under the rubric of "defense."

It's not unlike that new branch of federal government in charge of what used to be called "anarchists," or "reds;" now "terrorists." The agency could have been called "The Department of Terror" but that sounds a little, well, scary ... so "Homeland Security" it became. It has a more friendly ring to it, makes us automatically feel safer, at home.

It might have been a gift of the growing importance of public relations. The New York Times reports that even the Taliban has a PR Department, to give us a more positive view of their beheadings and bombings.

The Atomic Energy Commission from the 1950s and '60s was a veritable goldmine of PRitus. When they decided to start peppering Nevada with the atom bombs, they came up with winsome names for each of the blasts. Instead of "Fireball #5" or "Dustfire" or "Radiation Cookball" or "The Strontium 90 Stir-Fry" ... they announced tests with merry names like "Dixie," "Badger," "Encore," "Grable" (after the movie star Betty Grable) and, hold on, "Climax."

The first of the series, in 1951, was dubbed "Project Faultless." Another series was known as "Tumbler-Snapper." Another, to prove how homey it all was, was named "Operation Teapot."But all these above-the-ground tests --- exactly a hundred in number --- were no teapots. Some were so massive that their clouds of radiation shot up to 40,000 - 50,000 feet. With the prevailing winds, they effectively sprinkled radiation to the north --- as far as Idaho --- and east, to Boston. If you were alive in the United States at the time --- especially if you were in utero ... you got rads. Courtesy of the Feds.

The catchphrase was "Nuclear Arms for Peace," and there was nothing to worry about. As Ms. Ronald shows, in 1953, while people in the small community of St. George, Utah were being dusted with 100 times the official safe level of radiation from fallout, the Atomic Energy Commission was busy reassuring people that it was "nothing to be concerned about."

In 1957, atmospheric nuclear explosions in Nevada (with the name "Operation Plumbob") were later determined to have released enough radiation to cause up to 212,000 new cases of thyroid cancer amongst U.S. citizens, leading to as many as 21,000 deaths. This from a report issued by the National Cancer Institute in 1999.

Go to the full

reviewWhen I Was Mortal

Javier Marías

(New Directions)Marías takes an obviously wonderful plot line, and quickly sticks us right in the middle of it, sucks us into this shaggy-dog story, making it totally believable, making us want to go on with it, get to the end of it, or even better, us not wanting it to end. He spins his characters and us in a perfect tale, as perfect as most --- if not all --- of the twelve tales he conjures up in When I Was Mortal.Part of the richness is his mastery of dialogue:[says Lorenzo] you screw a woman a couple of times and you get fond of her. Well, not that fond, I've got a girlfriend too, and not because you have to, but it's different, you've touched her, you've kissed her and you don't look at her in the same way any more, and she treats you affectionately too." I wondered if I would treat him affectionately after the session awaiting us. Or if he would get fond of me because of that. I didn't interrupt. "So apart from the tension involved in the work, there was also the worry, not to say panic, I didn't want anything to happen to her, that was the last thing in the world I wanted. In short, it was a real bummer; compared to that, this is a breeze."

"But of course,

Go to the full

review

Gangrene and Glory

Medical Care During the American Civil War

<Frank R. Freemon

(Illinois)In the early days of the Civil War, elegant picnics were held on bluffs overlooking the battlefields, so that the on-lookers could watch the mayhem through their binoculars while sipping cider and eating fried chicken. An exceptional return on invested dollar came to those who supplied the guns, uniforms, ammunition, foodstuffs, and transportation to both sides. If you were rich, you could even pay for someone less well off to fight your war for you.We suspect it hasn't changed all that much. Young men with no assets --- usually black or Mexican American --- who long to escape from the vicious culture of the streets are seduced into the military with a promise of a living wage, education and "computer skills." Theirs are the bodies that are placed on the firing lines: certainly no President, Senator, or Representative would volunteer for service in the field, ducking missiles and anthrax bombs. They always prefer to watch the war they declared from the safety of their living rooms, making for them what Michael Arlen called "A Living Room War."

If one has any doubt about the profitability for certain businesses and stockholders --- especially for our newest venture --- one merely has to consult the pages of Businessweek, the Wall Street Journal, Barrons, or the financial pages of the local newspaper to see stocks being touted that will profit investors the most during times of war and biological terrorism: Lockheed-Martin, Wackenhut, Boeing, United Technologies, Honeywell, and the manufacturer of Cipro, Bayer.

The world, once again, gets to be made safe for democracy. Those who run the country get to lay their assets on the line, in hopes that they will skyrocket. Those who don't have the wherewithal will have to be content with merely laying their asses on the line.

Go to the full

reviewThe Little Girl Who Was

Too Fond of Matches

<Gaétan Soucy

(Arcade)It's hard to convey the strangeness of The Little Girl Who Was Too Fond of Matches. I started it, almost dropped it around page 25 --- but something in the weirdness of it kept me going on, so I got into it, got into it too much, got into it so much that I didn't want to stop --- and once I reached the end, I turned around and read it again.Soucy is able to plant clues, drop hints, lay the webs and traps in place so that at one point, I am saying (you will be saying) --- "Oh, no..." and then, later --- "Don't let it happen..." and then, finally, "Ah so --- now I get it."

It's a Kaspar Hauser book --- we meet a child out of the wilderness, dealt, during her brief life, a strange set of cards. Her father, her only contact with the world, never did explain the difference between boys and girls, so she thinks that she is one of two boys, except, lacking something down there (she figured she had been castrated). She explains all this using her father's neo-Biblical vocabulary.

By using his words, we get a wonderfully distorted picture, through her, of a very strange man. All women are "sluts" or "blessed virgins." Breasts are called "inflations." Male private parts are referred to as "attributions." Time is counted in "moons," and the house is "our earthly abode." She thinks with her "bonnet," and when she and her brother are to be punished, they are "given whacks." She is a "secretarious," a writer.

This strange vocabulary is of a piece, and it matches their strange circumstances: a boy and a girl raised by one so savaged by the world that he would never let them have contact with it. In addition, down in a nearby vault, he keeps something referred to as the "Fair Punishment." Or rather two somethings --- one dead, one alive and... and... no... I'm not going to tell you what gives. You have to go out and get this one, find out for yourself.

Go to the full

reviewThe Soul of

A New Machine

Tracy Kidder

(Back Bay)The Soul of a New Machine came out to much acclaim twenty years ago. It told the story of the development of a supercomputer at Data General in Building 14A just outside of Boston. The company had built its earlier fortune on the NOVA, one of such elegance and simplicity of design that the company was known as "the Robert Hall of the computer industry."The angle, the hook that sets The Soul apart from all your usual normal business success stories is that we get to live with and live in the heads of the people responsible for what was to become a dramatic step forward in the creation of storage capacity and speed and elegance of computers. We get immersed in their drive, their conflicts, their ideals, their hunger to do it. One might argue, the greatest competition was not on the outside but within their own fragmented, mechanically-

driven souls. Steve Wallach, Tom West, Carl Alsing, Ed de Castro are the names of the characters in this saga, but the strangest character of them all is the well-named EGO, the "new machine" designed to keep Data General competitive. What made it happen was what is known as "the compulsion to program:"

Bright young men of disheveled appearance, often with sunken glowing eyes [who play out] megalomaniacal fantasies of omnipotence...their arms tensed and waiting to fire their fingers, already poised to strike at the buttons and keys on which their attention seems to be as riveted as a gambler's on the rolling dice.

This is the soul of their "new machine."

Go to the full

reviewThe Airmen and the Headhunters

A True Story of Lost Soldiers, Heroic Tribesmen and

The Unlikeliest Rescue of World War II

Judith M. Heimann

(Harcourt)Towards the end of WWII, several American bombers went down in North Central Borneo, between what had been the Dutch and British parts of the territory. Seven of the airmen survived the crash and spent the next half-year trying to survive in the jungle.Borneo is the third largest island in the world, and at that time, may have been the least inhabited. Steep mountains, impossible trails, no large cities, vicious humidity in the lowlands and a rainy season of two-hundred inches a year tended to dissuade idle visitors.

There was malaria, TB, dysentery, along with an astounding selection of snakes, venomous pests, fleas and other flying, crawling, creeping, sucking and stinging bugs, plus thousands of hungry leeches hiding in the grasses alongside every river.

And then there were the Lun Dayaks. "The Dayak's religion was the belief that ambushing and taking the head of someone from a rival group and bringing it back to one's own longhouse could turn the head into a spirit that conferred health and good crops for the people of its new home."

The purpose had never been to decapitate a specific person. The idea had been simply to take a head from a rival group of one that caused trouble to one's own longhouse, and use its spiritual powers for the good of the longhouse.

The British and the Dutch outlawed this head-hunting business and brought in some good Christians to put the nail in the coffin, as it were. But you know how difficult it is to get the old folks to give up their crotchety habits of yore --- our pipe-smoking, our snifter of brandy after supper, our dried heads on the bedpost.

The seven airmen ... joined later by four others who crashed in the forest near-by --- ended up being cared for, and not head-hunted, by the Dayak. Why? These "savages" were not dummies. They had been living under Japanese rule for more than three years. When the Americans appeared, their first question was: "Who's going to win this war?" The agreement was universal. Sooner or later, the Greater Asian CoProsperity Sphere would be a dead duck. More than that, the stuffy Dutch and the British were now encouraging the head-hunting of yore. If the heads were Japanese.

Go to the full

reviewBritish Wood-Engraved

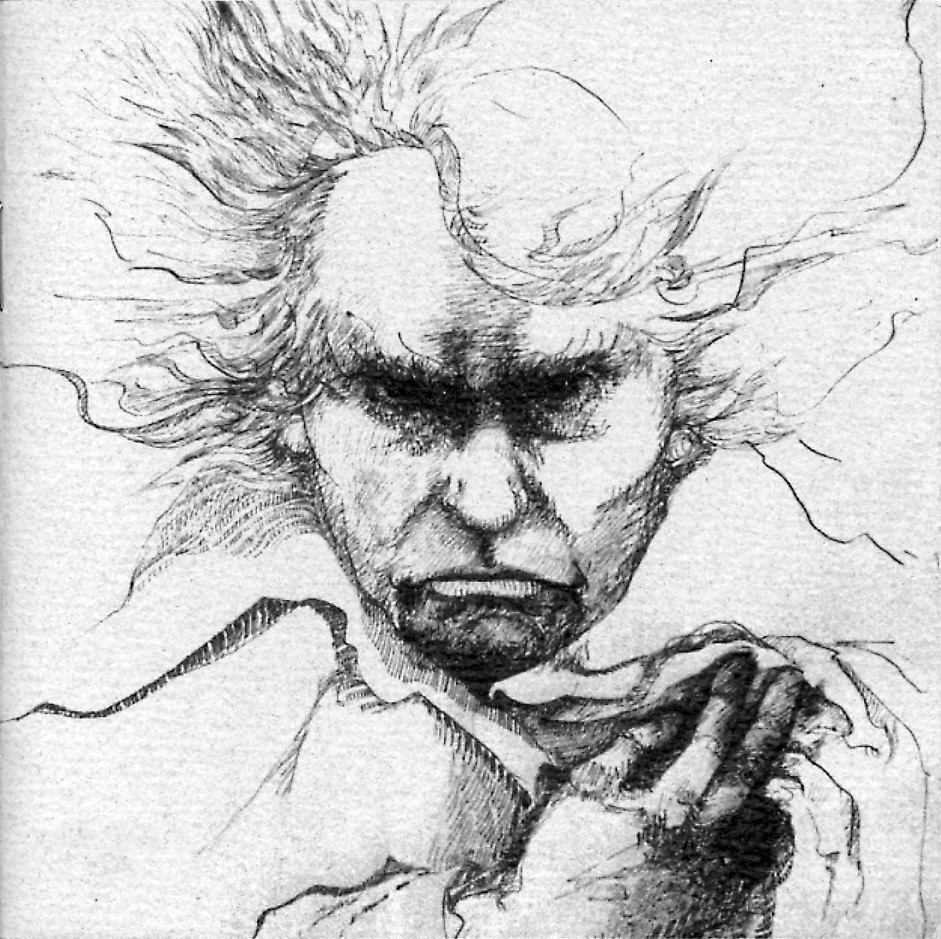

Book Illustrations 1904 - 1940A Break with TraditionJoanna Selborne(Clarendon Press/Oxford)Pioneering wood-engravers such as Eric Gill, David Jones, Philip Hagreen are well-represented here: in fact, this 400+ page volume contains over two hundred plates, running from the pioneers to pre-WWII artists such as Agnes Miller Parker, Mary Groom, Dorothea Braby, and Blair Hughes-Stanton.The text is nicely informed, and the wood-

engravings so gloriously presented that we were thinking that fine books like this should be outlawed. You pick it up to leaf through it, to start a review, and two hours later, dazed, you lay it down, regretfully, because you feel guilty at spending yet another minute without writing on a subject as abstruse as this one --- with such stupendous visual rewards. In fact, the best thing I can think of to do with British Wood-Engraved Book Illustration is to tear the son-of-a-bitch to pieces --- not in rage, but in love. To cut out Robert Gibbings illustration for "Lamia" (man, woman, palm-trees). Or to eviscerate pages 231 - 239 and extract Robert Gill's lovely, lurid representations of "The Song of Songs." Then to gouge out pages 101 - 104 and mount Paul Nash's "Three Carts" on the refrigerator door. Maybe, as well, to brutally excise Plates 82 - 85 --- being illustrations by John Farleigh of Shaw's play, The Adventures of the Black Girl in her Search for God --- to stick them on the wall behind the computer to contemplate again, and again, and yet again.

And, best of all, to amputate the pages containing "The Nuptials of God" (see Fig. 1 above) by Eric Gill such a delicious take-off. We'd haul it down to The Blow-Up Photo Shoppe, turn it into a six- by twelve-foot poster to hang at the top of the bed, so we can see it, in love with it, as we are with love ... every day, and every night.

Go to the full

reviewWhy Is Beethoven

So Different?Beethoven did not shrink from presenting the listener (and the performers) with complexity.The music of his immediate predecessors is much simpler, in all but a very few cases. Mozart composed a great fugue for the last movement of his Symphony Number Forty-One, but otherwise used counterpoint very rarely, and Haydn even less. Conventional music of the period almost always followed the monophonic structure of a melody line over a chord-based, oompah sort of accompaniment. This, like the plodding, regular rhythms, illustrates the defining feature of the pre-Beethoven classical style: it is Easy Listening. That is precisely why commercial classical music stations program so much of it. It is as if Haydn & Co. anticipated exactly what the broadcast industry, and the purveyors of background music for elevators and telephone waiting, would require two centuries later.

Since Mozart demonstrably knew how to write a fugue, and perhaps Haydn did too, the avoidance of counterpoint must have been a matter of policy. So, I believe, was their avoidance (with very rare exceptions) of the minor key. Haydn & Co. must have calculated that patronage would be more forthcoming for works filled with forced gladsomeness. The result is a sensibility resembling a cross between highschool cheer-leading and "socialist realism" in the old USSR; it conveys to me a powerful sense of calculated pandering. Haydn & Co. pander to their audience, while Beethoven, in contrast, tries to engage it.

Go to the full

review

William Faulkner

Novels, 1926 - 1929

Flags in the Dust

(The Library of America)For a novel to work, we need a place, and a time, and, oh, words. Suddenly, starting at age twenty-eight or so, this Faulkner has the words, the right words. He wasn't much for talking, even when he got before the Nobel Prize people, they couldn't understand his Mississippi accent, and he was too far from the microphone (he had little interest in being heard in day-to-day speech).But the written word. His heaven, in Sartoris, is a place where

no star showed, and the sky was the sagging corpse of itself. It lay upon the earth like a deflated balloon; into the dark shape of the kitchen rose without depth, and the trees beyond, and homely shapes like sad ghosts in the chill corpse-light --- the woodpile; a farming tool; a barrel beside the broken stoop at the kitchen door, where he had stumbled supperward.

And the characters: Flem Snopes writing illiterate, scary, nasty letters to Narcissa; Simon, the oldest servant in the family, who takes but one ride in the car and then demands to be let out; the old colonel, napping in front of his bank; Horace Benbow, who falls for Belle, wife of cotton speculator Harry --- Belle, who asks him, before she dumps Harry, if he is rich; (he lies, and she never forgives him); and the blacks, always in the background, often haranguing those they are supposed to be "serving." Rachel, telling Harry, "Whut you let that 'oman treat you and that baby like she do, anyhow? ... You ought to take and lay her out wid a stick of wood. Messin' up my kitchen at fo' oclock in de evenin'. And you aint helpin' none, neither," she told Horace.

"Gimme a dram, Mr Harry, please, suh." She held her glass out and Harry filled it.

Simon is the house black who eats a mix of spinach and icecream and between bites tries to feel up the young black girls in the kitchen. Oh, too: trees and the birds and the gardens:

the garden lay in sunlight bright with bloom, myriad with scent and with a drowsy humming of bees --- a steady golden sound, as of sunlight become audible --- all the impalpable veil of the immediate, the familiar.

Go to the full

review

African Sculpture

Warren Robbins

(Schiffer)Robbins says that to call this art "primitive" is a result of a "non-African inability to understand it." A better word, he offers, would be "classical" since Africa has a long and honored tradition of putting beliefs and social systems into concrete representations.The emphasis in traditional African art --- what westerners might think of as exaggeration --- is four-fold: the head (indicating character), the navel (suggesting continuity), the genital (a tribute to generative power), and animal horns and tusks (representing fertility).

All African art is "abstract," says the editor, because purely representational art is neither desired nor valid in the cultures represented. He compares the many masks shown here --- all of ceremonial or authoritative value --- as not being unlike ceremonial wigs or robes of European or American judicial bodies.

Evidently the first Western artists to immerse themselves in African art were the German expressionists --- Nolde, Kirchner, Heckel, Schmidt-Rottluff and the most famous of them all, Erich von Hansenpuklebafentrubenhabenbaben. I concocted this name to be sure you were paying attention to your lessons (we'll have a quiz tomorrow).

Go to the full

reviewThe Louisiana Purchase

Joseph J. EllisGiven the triumphal tone of most histories of the Purchase, and the somewhat silly scramble to assign credit for the triumph, it is curious that Jefferson himself made a point of not listing it on his tombstone as one of his proudest achievements. Nor did he list his presidency, in which the Purchase was unquestionably his singular accomplishment. As we shall see, there were several reasons for this omission, and modesty was not one of them.Perhaps the best way to put it is that there is a tragic as well as triumphal version of the story. As one version moved gloriously and inexorably toward the Pacific, the other moved ominously and just as inexorably toward the Civil War, whose immediate cause was the debate over slavery in the territory Jefferson had done so much to acquire. Indeed, the tragedy was double-barreled, since the Louisiana Purchase also proved to be the death knell for any Indian presence east of the Mississippi. And since the failure to end slavery and the failure to preserve and protect the indigenous peoples of North America were the two great stains on the legacy of the founding generation, the fact that the Purchase locked these failures into place was not an achievement Jefferson wished to advertise.

We could begin the story around 15,000 B.C., with the retreat of the glacial ice that formed the Mississippi Valley. But since we are doing history rather than geology, a more appropriate starting line is March 6, 1801, as Jefferson ascended to the presidency after one of the most controversial elections in American history. In his inaugural address, destined to become one of the best in the genre, he outlined the principles that would guide him, which were essentially the same principles that had shaped the agenda of the Republican Party over the past decade: "A wise and frugal government which ... shall not take from the mouth of labour the bread it has earned;" a reduction of the national debt, made possible by a slashing of all federal budgets and a transfer of all domestic policies to the states; an innocuous and almost invisible executive branch, rendered even more inconspicuous by Jefferson's decision to file all presidential correspondence with the relevant cabinet officers in order to eliminate even a presidential paper trail. These were "the ancient Whig principles," the values of "pure republicanism" that the Federalists had betrayed, what Henry Adams called "the strange hymn" that Americans "had learned to chant with their chief." These were the cherished principles Jefferson proclaimed. He was about to violate every one of them.

Go to the full

readingThe Anatomy of Addiction

Sigmund Freud, William Halstead,

And the Miracle Drug Cocaine

Howard Markel

(Pantheon)

The Anatomy of Addiction focuses on the dopey habits of two contemporaries: Sigmund Freud and William Halstead. Freud we all know about, with his weird ideas about mothers and fathers and sexuality (which may, in retrospect, not be so dopey, if you had to put up with my mother and father). Halstead was the American counterpart of Freud, operating mostly at Johns Hopkins University. Along with three other medical professionals, he practically dragged American medicine into the present precise, ritualized field that we know today.According to Markel, Halsted invented several medical techniques: operations for goiters, inguinal hernias, and aneurysms, the removal of gallstones, and radical mastectomies (now no longer used, but in the dark ages of medicine, the only hope for a woman with breast cancer).

Most of all, he implemented Lister's demands for a germ-free / bacteria-free operating theatre. In fact, his demands for pre-operating scrub-downs were so ruinous to the hands of his assistants (and his future wife) that he went off to New York and told B. F. Goodrich himself to make a glove that was suitable for doctors to use when cutting people, reminding us of that romantic trochee by the ever-famous Anon:

There was a man with a hernia

Who said to his doctor "Goldern-ya,

When cutting my middle,

Be sure you don't fiddle

With matters that do not concern-ya."During his time at Johns Hopkins, Halsted was, according to Markel, sticking cocaine in his arm. It was known and accepted that he had been an addict during his student days, but Markel's contention here is that Halstead continued to have a lust for both cocaine and morphine until his death in 1922; indeed, that the drugs probably hastened his demise.

William Halsted, Markel claims, "was a remarkably high-performing addict for almost four decades."

Armed with a controlling personality of epic proportions, more times than not the surgeon restricted satisfying his drug hunger to a precise schedule of furtive morphine injections. He also managed to contain his cocaine cravings to those safe periods when he was far away from the hospital and could afford to binge.

The author's respect for Halsted comes partly from what he did to make American medicine respectable ... indeed, to make it the wonder of the Western world. But Markel seems to think less of Freud. Even though, apparently, the good doctor of Vienna was able to shake off his twelve-year addiction to cocaine and soon went on to shape his astonishing theory of the way the mind works, and in the process, to write one of the great novels of the 19th Century, The Interpretation of Dreams. (Others refer to it as a scientific paper or some such. Forget it. It's as good as that other bleak novel of 19th Century life, Das Kapital.)

Go to the complete

selection