Wide Awake

Poets of Los Angeles and Beyond

Suzanne Lummis, Editor

(Pacific Coast Poetry Series)

Having just put together an anthology of poetry myself, I can tell you, merely assembling it all ain't no bed of roses. Tracking down poets, or the owners of the rights to their poems; negotiating a fair price; sometimes treating with indifferent publishers (who often don't even know the rights they own); dealing with the (at times) testy artists themselves, who've been screwed so many times they are wily, sometimes infuriatingly hard to get; and most of all, the interminable proofing, because one knows poems have to be exactly right on the page, down to fine points of indent, end-stops, and balance.All this can give one heart-burn, dyspepsia and insomnia. Therefore cheers to Ms. Lummis for cadging together 112 poets and hustling them all together in one fat book.

And, after spending the last three days immersed in her selection, we must praise her for finding --- at a minimum --- over a hundred that may be worth their salt, and of these, a quarter bringing fit credit to the editor, to the authors, to the anthology itself.

After fifty years of vetting poetry, I have learned that the Common Denominator that we think of as endemic to poetry does not exist. Because of that, we don't need to pay credence to the gushers of one writer versus the waspish output of another. Quality does not equal quantity. Nor, I think, do prizes, honors, special appearances or grants matter all that much.

For the official judges of poems and poets usually are not the loonies who produce the stuff. The professional winnowing field tends to gravitate to the academics, and these are the last people we would want to have the power to separate the glorious from the ghastly.

As consumers, you and I are forced to rely on our own poetic sense, something that begins to come after years of composing our own, plus endless days weeks months burrowing through old magazines, posters, anthologies, broadsides, and --- nowadays --- online sites.

And, we find, after we do this poetry stuff long enough, we can learn to trust our own sensibility, looking, for example, for the poet who militantly purges the tired phrase, peels away the oft-repeated trope, the wan parallel.

We can also demand that what we are presented with be not coy. We don't want phrases that puzzle and then, once you tease out the spooks behind the paradox, you find yourself dealing with a writer who is nothing but that Johnsonian harmless drudge.

And, finally, and this has occurred to me just recently, we must seek poems that will offer us a gentle twist, the equivalent of what the littérateurs think of as the watershed of a novel, the point where the author, the reader and --- presumably the characters --- have no choice, cannot turn back. The equal in a poem would be that turn of thought that --- if done right --- permits the reader to see that what we hold in our hands is an entirely new crystal, bent, shifted, torn by a different light entirely.

I think, as an elegant example, on the savage turn of the very last lines of Larkin's "Money," where, after listing the commonplaces, he suddenly comes up with this breathtaking switch-hit:

I listen to money singing. It's like looking down

From long french windows at a provincial town,

The slums, the canal, the churches ornate and mad

In the evening sun. It is intensely sad.It is this same exotic gyre that we come across in a recent LRB explication on Elizabeth Bishop's poem "At the Fishhouses." What is it like, the poem asks, to sip salt water?

If you tasted it, it would first taste bitter,

then briny, then surely burn your tongue.

It is like what we imagine knowledge to be:

dark, salt, clear, moving, utterly free,

drawn from the cold hard mouth

of the world, derived from the rocky breasts

forever, flowing and drawn, and since

our knowledge is historical, flowing and flown.Matthew Bevis, the reviewer, concludes, "The ending is also a testimony to her sense of what poetry could be: a reaching of one's limits, and a release into the wild. Frank Bidart once told her how great the poem's closing lines were, and recalled her response,"

She said that when she was writing it she hardly knew what she was writing, knew the words were right, and (at this, she raised her arms as high straight over her head as she could) felt ten feet tall.

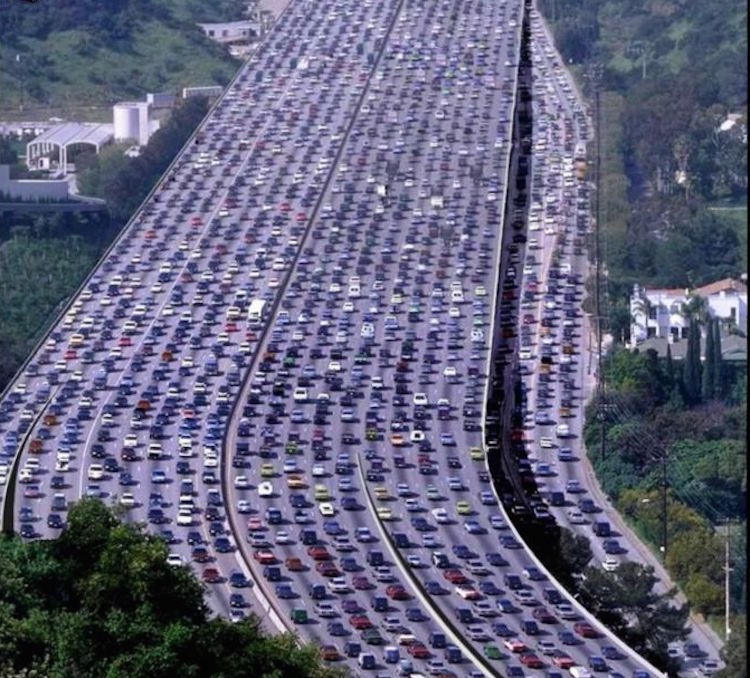

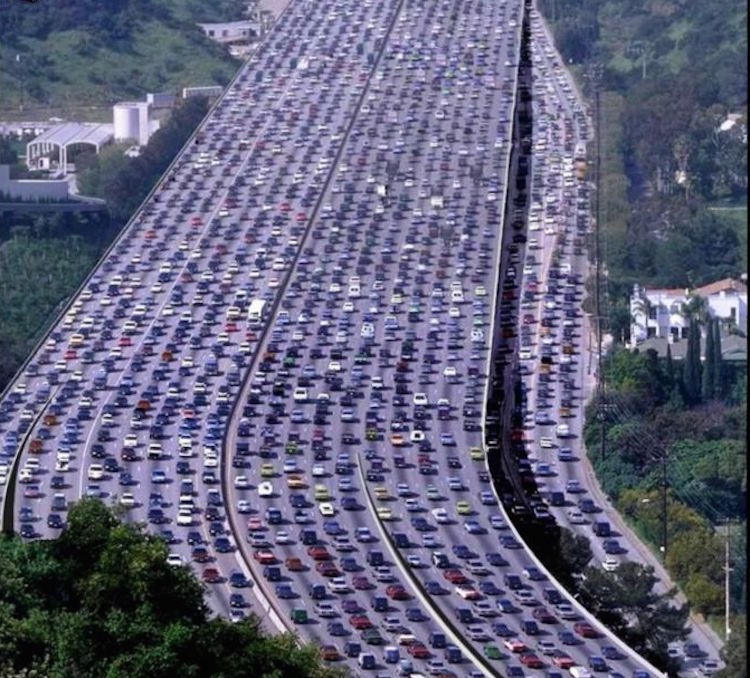

§ § § Wide Awake is bulky, suffers from one always finds in a fat volume. Too much stuff. 235 poems, I think, may be overkill. In an anthology, we want slimming down of choices which must come from an editors' point-of-view. A massive collection --- like Los Angeles itself --- doesn't allow you to find one key point, one common theme (in this case freeway-smog-far-flung-excess-too-much-cement/cars/people/confusion).

Consequently there are only few of the poets who are able to capture that too-much/not-enough soul of it all. One of the best is John Brautingham's "Los Angeles" which manages to find poetry in rhythmic highway numbers, and, at the same time, can play along with the region's dangerous underpinnings:

My love for you, King Smog,

is the love of an old woman

for an old man. I love you with all

of your faults, even sometimes because

of your faults. I love your freeways,

your 5, 405, 605, 105,

your 10, 210, 110, 710,

and for your pesticide beaches

choked with human waste too dangerous

to bathe in but too beautiful

not to.What's more, with so many choices here, we must look for the special, the odd, the brazen, the facetiously charming. Like the report of David Hernandez's seductively bad taco, to be found in his "Dear Professor,"

Let me explain my lengthy absence ---

My entire family got food poisoning,

myself included. We had eaten rotton

fish tacos, old bad cod, I've never been so

nauseous, the house wouldn't stop

spinning, wouldn't stop shuffling

its windows, I was gushing from

I'll spare you the details.Note the elegant line break and apologia after gushing, then we go on to hear of wild rides, flat tires, sparks on the highway --- a true L. A. tribute to the cars of our lives, ending with the same charming brazen trick that those of us who have passed too much time as "adjunct professors" have always had to fend off,

. . . I want

to live forever. I want to pass your class

and graduate, get a gig, marry some hottie,

see the world, drive until my wheels

come wobbling off, and keep driving

but first I need to pass your class.

No pressure. Honestly. No pressure.§ § § Enough. If you pick up Wide Awake, do not --- repeat --- do not be put off by the lousy cover, with pink words splayed across the dirt brown smoggy ink that makes the title impossible to read. Do not, also, be put off by the pro forma typestyle within, the hum-drum layout, the needlessly crowded pages, and the miserable proofreading (poetry books that contain a fair number of Spanish words and phrases must be prepared to offer appropriate and correct accents, tildes, and diaeresis).

Do, however, look for the likes of Brautingham and Hernandez, and as well, Liz Gonzalez, Kate Gale (she turned up in our own anthology), Dana Gioia, Gloria Vando ("My 90-Year-Old Father and My Husband Discuss Their Trips to the Moon"), Patty Seyburn, R. H. Fairchild (the longest rave in the book, five pages, titled as it should be, "Rave On,") Cecilia Woloch, Luís Campos, and Candace Pearson's altogether too sad family,

My brother will be dead in two weeks, I'll be in some other city

when he overdoses on downers as our parents drink double

vodka tonics in another room, I'll get a call at 2 am. Someone

will say, This is your mama speaking. And I will answer, Who?And spend a moment or two with Patty Seyburn, who wants us to know, apropos of nothing, what she dislikes most about the pleistocene era,

The pastries were awfully dry.

An absence of hummingbirds ---

of any humming, and birds' lead

feathers made it difficult to fly . . .

Clouds had not yet learned

to clot, billow, represent.

Stars unshot, anonymous.

Moon and sun indifferent . . .

And I was not yet capital I.

Still just an eye. No mouth,

no verb, no AM to carry dark

from day, dirt or sea from sky . . .--- Lolita Lark