You Might As Well Start Doing

Godly Things. Like Waking Up.

Over the past twenty years, we have sought out many rare or obscure

books of a mystical bent, works that may come from the far reaches

of the mysterious East or even from home-grown gurus closer to home.

These include masters who have the ability to deliver a no-nonsense message,

a hard-headed approach to the divine

offered without the usual mush of most Western religions.

Here are more than a dozen readings or reviews that look to

that special divine which, they tell us,

resides gently if not quietly within all of us.

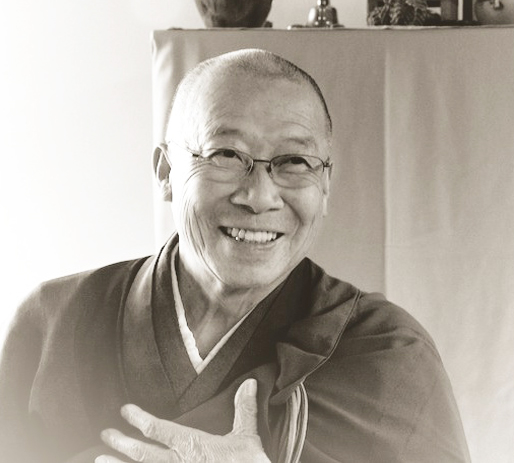

Novice to Master

An Ongoing Lesson In

The Extent of My Own Stupidity

Soke Morinaga Roshi

Belenda Attaway Yakakawa,

Translator

(Wisdom)This religion is not for kicks. The theory and practice of it is not unlike that of a Marine on Parris Island, or one being admitted to a federal or state prison. The marines want to teach recruits to kill. Prison authorities want it so none will ever return. For a Zen monk, the discipline forces a possibility of seeing the Truth. Morinaga makes it clear that in the pursuit of this truth, one must suffer --- not only with the cold, bare deprivation of the life of a Zen monk, but the continual battle to yield up the ego, and finally get the koan --- the riddle which has no answer, but is used as a gateway to final enlightenment.If Novice to Master were just the story of being a monk at Daitokuji, it would be worth reading. But it is far more. It is the story of a man's devotion to getting it --- whatever it may be. It is a codex on the worth of such a pursuit. Most of all, a picture of a profoundly devoted master.

The last part of the book lets us watch Morinaga finally getting it, and it is definitely not the Buddha Middle Way.

After meditating in the cold, twenty to twenty-fours hours of the day, not sleeping, giving up food (because he thought it made him sleepy), doing nothing but pursuing his goal, for weeks and months ... when, suddenly,

I lost all sense of wanting enlightenment; to continue seeking satori was inconceivable...My whole body was a mass of sheer pain. It was not "I" sitting on that cushions; it was sheer fatigue. As if consciousness were lost in a fog, all was hazy.

And then,

Suddenly, under some impetus unknown to me, the fog lifted and vanished. And it is not that the pain in my own body disappeared, but rather that the body that is supposed to feel the pain disappeared. Everything was utterly clear. Even in the dimly lit darkness, things could be seen in a fine clarity. The faintest sound could be heard distinctly, but the hearing self was not there. This was, I believe, to die while alive.

Most importantly,

It never crossed my mind that this was a satori experience or that "I had kensho." Without any theorizing, I felt only the brimming joy of having had a heavy burden suddenly swept away.

In other words --- the only way to get it is to not get it. Got it? Good.

Go to the complete

review

The Roots of Buddhist Psychology

Jack Kornfield

(Sounds True)There are the four noble truths, the six senses, the eight-fold path, the 10,000 sorrows and the 10,000 joys. There are the masters, asking such questions as "How come you want what you don't have and don't want what you do have?"There's wanting, and avoiding, and being gooned out. Grasping and gimme more and if I have it I'm going to be happy. There's also fear, pushing away, it hurts too much, I can't take it any more. And finally, confusion --- "What am I doing here? Who are all these people? What is going on?"There's walking through the rice paddies at dawn carrying the begging bowl and the sun coming up and the mist and the feeling of peace, knowing that the people give to you not because they have to but because you represent the sacredness they hold most dear. It's the mystery of gravity, the mystery of the galaxies, the mystery of the heart.There's the Eskimo and the priest, the priest telling the man about sin and going to hell and the Eskimo asks,

"Do those who don't know about what you are saying go to hell, too?"

"Well, no..."

"Then why did you tell me?"

There is Jesus looking around heaven, seeing these drunks lying around, others gambling and carrying on. So he goes to St. Peter and says, "Why are you permitting these people to come in?" And St. Peter says, "Don't blame me. It's your mother. Every time I turn someone away she lets them in the back door."

reading

Hindu Mysticism

S. N. Dasgupta

(Open Court) Here is a little book by the professor of Presidency College, Calcutta, which offers salubrious reading to those persons who still labor under the delusion that the Hindus are privy to a store of wisdom hidden from Western eyes, and that their religion is, in some vague way, more refined and civilized than Christianity.

Here is a little book by the professor of Presidency College, Calcutta, which offers salubrious reading to those persons who still labor under the delusion that the Hindus are privy to a store of wisdom hidden from Western eyes, and that their religion is, in some vague way, more refined and civilized than Christianity.Professor Dasgupta, it appears, shares that notion himself, but he is too honest a man to conceal the facts that blow it up. Those facts he arranges neatly in six chapters. They show conclusively that the theology of even the most enlightened Hindus is almost as barbaric and nonsensical as the theology of the Swedenborgians or Seventh Day Adventists, firmly upon a bibliolatry precisely similar to the Christian bibliolatry --- nay, upon one that is far worse.

The Christian Fundamentalist at least tries to make himself believe that the Bible is a record of actual human experiences, and that its mandates do no violence to that wisdom which has come out of human trial and error. But the Hindu accepts the Vedas as completely transcendental --- and yet completely binding.

Go to the complete

review

Autobiography of a Spiritually

Incorrect Mystic

Osho [Rajneesh]

(St. Martin's Press)You remember Rajneesh, right? Furry cap, dark glasses, ashram in Antelope, 77 (or was it 87?) Mercedes, beautiful young ladies packing mean-looking rifles, rumors of poison sprayed on nearby salad bars, neighbors in an uproar, the master finally banished from the U. S., spending his last days in India.Rajneesh, we find here, has come back again, disguised as "Osho" --- the name he gave himself before lapsing into his final silence. You wouldn't know it was Rajneesh at first glance, so it's a bit like the editors at St. Martin's were thinking, "We know that people probably still find Rajneesh's reputation a little dicey. So how can we get people to pick up his autobiography? How about we change his name? They'll be sucked in before they can figure out the real skinny." And so they create "Osho."

But, in truth, this isn't Rajneesh's autobiography. What the editors did was to weed though all his previous writings, plus 15,000 hours of tapes --- Rajneesh couldn't keep his mouth shut; that's what got him into so much hot water --- and come up with this hotch-potch.

And it is very much a potch. There are some when-

I- was- young stories, an extensive discussion of his enlightenment, a discourse on how popular he was in India before he came here (audiences of 15,000!) And then it sort of peters out into the scandals at Big Muddy Ranch, getting in trouble with various authorities, and, we're told, getting poisoned by the U. S. Government while they were flying him around the country (thallium --- can't be traced) and before you know it, he sickens and dies. Go to the complete

review

Emanuel Swedenborg's

Journal of Dreams

Commentary by Wilson van Dusen

(Swedenborg Foundation)Swedenborg's change came about in 1743 - 1744, and his visions came to him through dreams. He, being a scientific type, carefully recorded them. We have 286 of his dreams, reproduced in full here, with commentary by psychologist Wilson Van Dusen. Van Dusen points out that, if nothing else, this is probably the only full recounting of one man's dreams from so many years ago. (In those pre-Freudian times, dreams were not viewed with the same regard as now).What is particularly fascinating about Journal of Dreams is not so much Swedenborg's night visions, for most people's dreams are so personal as to be almost meaningless. Rather, it is the editor's excellent understanding of the dream process. In fact, Van Dusen's Introduction is one of the best primers extant on how dreams occur, what they mean for the individual, and how one should look at them. Because he is so eloquent --- as eloquent we think, as Emanuel Swedenborg, and a hell of a lot less daffy --- one can see a system of dream-vision which makes sense to the average reader.

Once you get used to the peculiar language of dreams they become a personal guidance system with a superior overview of the nature of one's own life. As a clinical psychologist, understanding my own dreams is a prerequisite for working on a client's dreams... Dreams are valuable guidance system. Should I be in error with Swedenborg's dreams, I would expect my own personal guidance system to tell me so. I need my own dreams to monitor my understanding of his. This might surprise you. But when you are working on something, especially when it is close to your life concerns, your dreams will tell you how well you are doing.

Go to the complete

reviewThe Gateless Barrier

Zen Comments on the Mumonkan

Zenkei Shibayama

(Shambhala)In contrast to the wizened surety of the Episcopalians or Southern Baptists or the 700 Club ... in Zen, there are no answers. As soon as you think you have figured it out, you are wrong. The answer, it turns out, is another question; and that question leads to yet another. "What was the face of your parents before they had a face?" "Can a dog have the Buddha nature?" "What is the most valuable thing in the world." (The answer to the last is, but of course, "the head of a dead cat.")These questions --- and their improbable, non-informative, and indeed looney, answers --- are known as "koans." They are not to satisfy those of us to the west who are seeking a Truth. They are, instead, to put off the inquisitive, non-stop, babbling mind from the belief that there can be answers to the Big Questions; they are to show us that to the biggest questions of them all --- "Why are we here?" "Why me?" --- are, have been, and always will be, unanswerable.Go to the complete

reviewSilence

50th Anniversary Edition

John Cage

Kyle Gann, Editor

(Wesleyan)Silence is infinitely quotable, mostly because of the koans. All are a bit floaty, so Cage sticks in names and places and details that leave one befuddled, but you have all the facts you need to befuddle you somewhat less. "Before studying Zen, men are men and mountains are mountains. While studying Zen, things become confused. After studying Zen, men are men and mountains are mountains."After telling this, Dr. Suzuki was asked, "What's the difference between before and after?" He said, "No difference, only the feet are a little bit off the ground."

When Cage wasn't driving people bonkers by repeating the same line over and over, or playing fourteen radios at once, or trying to put people --- or himself --- to sleep, he would attack a few pages of his writings with spaces, breaking up sentences and paragraphs into random hunks. In this one, you'll find four vertical lines --- blocks of words and em and en spaces, all of which have to be a typesetter's nightmare. I couldn't figure out how to reproduce them here even if I tried, so I didn't. He would have wanted it that way.

John Cage and I grew up on Cracker Jacks: we knew that there was always a prize at the bottom of the box after you got through the glazed popcorn. Prizes in Silence include charming thoughts on mushroom and wild plant collecting ... including an account of the time he almost killed himself and several friends. He made a mistake on the identity of skunk cabbage, cooked it and served it up to some buddies. "I was removed to the Spring Valley hospital. There during the night I was kept supplied with adrenaline and I was thoroughly cleaned out. In the morning I felt like a million dollars."

Go to the complete

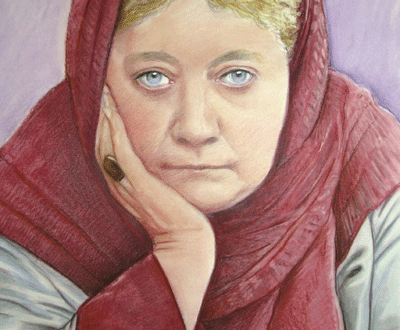

reviewThe Missing Tiger

Madam Helen BlavatskyBut where was Gulâb-Singh? On the spot where he sat so motionless but a minute earlier, there was no one to be seen; only the topi lay there, torn down by the wind. Suddenly an awful roar, deafening and prolonged, made me jump; penetrating into the vihâra, it awakened the silent echoes and resounded along the edge of the precipice like the dull rumbling of thunder. Good heavens! A tiger! Before this thought had time to shape itself clearly in my mind, there came the sound of crashing branches, and of something heavy sliding down into the abyss. Everyone sprang up, and all the men seized their guns and revolvers. The alarm was general."What's the matter now?" said the calm voice of Gulâb-Singh, seated again on the bench as if nothing had happened. "What has caused you this fright?"

"A tiger! Was it not a tiger?" came in rapid questioning remarks from Europeans and Hindus alike. Miss B. trembled like one stricken with fever.

"Tiger or not matters very little to us now. Whatever it was, it is by now at the bottom of the abyss," answered the Râjput, yawning, "You seem to be especially disturbed," he added with a slight irony in his voice, addressing the English lady who was hysterically crying, undecided whether to swoon or not.

"Why doesn't our Government destroy all these terrible beasts?" sobbed our Miss B., who evidently believed firmly in the omnipresence of her government.

"Probably because our rulers save their powder for us, giving us the honor of being considered more dangerous than the tigers," said the courtly Gulâb-Singh.

Go to the complete

readingBreath Sweeps Mind

Jakusho Kwong Roshi

(Sounds True Audio) He tells stories, wonderful stories, about his roshis. One of them decided to do begging practice on the streets of San Francisco. He put on his robe and the straw hat that hid his eyes and picked up his begging bowl and told the sangha that he was going out to beg in the Fillmore, the black section of San Francisco.

He tells stories, wonderful stories, about his roshis. One of them decided to do begging practice on the streets of San Francisco. He put on his robe and the straw hat that hid his eyes and picked up his begging bowl and told the sangha that he was going out to beg in the Fillmore, the black section of San Francisco.The students were concerned, but he refused to take anyone else along with him. Kwong wondered how the people of the area would respond to this tiny man in his robe with his great straw hat and his begging bowl. When he returned several hours later, he had in his bowl "two silver quarters and a pomegranate."

There are times when Kwong has the ability to make us merry --- he comes across as a very merry person --- as well as touch the heart, touch it deeply. One night he was returning to San Francisco with his family and they arrived at a street corner where a car had just overturned, virtually split in two. One of the two passengers had been thrown out, and was lying in the street, on his back, lying in a pool of blood. Kwong ran to his side and knelt down. He tells us that the young man's eyes were open and bright and he was looking up at the skies. He looked at Kwong and said, "The stars are bright tonight." Kwong responded, "Yes --- they are very bright."

Go to the complete

reviewHolding the Lotus to the Rock

The Autobiography of Sokei-an,

America's First Zen Master

Michael Hotz, Editor

(Four Walls Eight Windows)Sokei-an studied carving, Buddhism, and Western philosophy in early 20th Century Japan. Then he came to the United States, where he worked as a janitor in a roller-rink, at a tavern --- and as wood-cutter, sculptor, student, and farmer. He walked throughout the northwest, and, after returning briefly to Japan, came to live permanently in New York City.In the early days, it was difficult getting students. The reason? Because a Zen master does not advertise. "Many Zen masters wait for a longer time. Usually they will not start any teaching until someone finds them out, so they hide themselves in obscurity."

The more he is hidden, the more effort people must make to discover him. Precious things are always hidden; they are never exposed on a street corner. If you have a diamond, you will not leave it on the corner of your desk. You will certainly keep it somewhere so that a stranger cannot find it. True things try to hide themselves. It is only natural.

Holding the Lotus to the Rock is Sokei-an's autobiography, but it also is a primer on his school of Zen --- Rinzai --- as opposed to the Soto school. As he says, "To use an analogy, the Soto school is something like a musical instrument, the strings of which are loose, so you cannot play a tune, though the sound is deep. The Rinzai school is like an instrument in which the strings are all tight. Just touch the strings, and they make a sound." In other words, "Reality is to be grasped in its most active moment."Go to the complete

review

The Zen Monks and the GovernorIn South Korea there is a famous mountain called Ji Ri Sahn Mountain, and on this mountain there is an ancient Zen temple, called Chon Un Sah Temple. It has been there for many hundreds of years, and was built even before Zen was a great movement in Korea. For centuries, the temple was supported by the devoted lay Buddhist people in the area, and also by the region's governor, who was a devout Buddhist himself.One year, a new governor was appointed to that region. He was a Confucian, so he didn't like Buddhism at all. Buddhism had been a national religion in Korea for many centuries when Confucians took power during the Chosun Dynasty (1492-1910), and Buddhism was often repressed by different kings and local officials. Buddhist monks in particular had a very difficult situation.

So in those times it was quite usual for the new governor to make trouble for the people who had anything to do with the temples in his district. One day. he summoned the temple's abbot. When the monk arrived at the regional office, the governor didn't say a word, and simply hit him on the top of his head very hard. "Why did you hit me?" the abbot asked.

"You're very bad," the governor replied. "Your students don't do any work. They only sit in that meditation room all day, doing nothing for hours on end. I see all these hardworking people give them food, and the monks only eat, lie down, and sleep. I don't like that! They're all a bunch of rice thieves! Everyone in this world has to work, but not these monks of yours. So now you must pay higher taxes to the government." Then he hit the abbot a few more times.

Go to the complete

readingBuddha Da

Anne Donovaan

(Carroll & Graf)If this were just a piece of fiction in funny language, there wouldn't be anything to write home about, would there? But by my troth, Donovan knows how to construct a story, get us in to it so we love (and sometimes hate) these Glaswegians, get it so that their problems become our problems. I am reading this and thinking what it must have been like reading Dickens when he was coming out in the weeklies so that you had to wait seven days before you could see how he was going to resolve Pip's dilemma, or get another funny story out of the Pickwickians.It isn't easy. While reading Buddha Da, I did, after all, have to do other things with my life, like breathe, eat, and sleep. Donovan knows how to construct a world filled with people from our neighborhood, funny new people we come to know ... and it almost takes away the desire to do anything else rather than go along with them. This is Anne Marie as she is listening to the lamas:

Ah love singing and maist of the time ah just dae it, never really think aboot it, but sometimes ah feel as if ma voice is comin fae somewhere else, that it's no me singing. Ah mind wan time when ah was rehearsin for the concert and it wis just me and the music teacher in the room. Ah shut ma eyes and it was like ma whole body was vibratin, like ah was a musical instrument and somebody was playin me. As could hear ma voice fae a great distance. When ah finished there was silence in the room. Ma teacher never made any comment, just sat. And listenin tae the lamas ah felt the same way. As thought they were musical instruments and the music was comin through them. And the sounds they made, that at first seemed harsh and discordant tae me, had become the maist beautiful sounds ah'd ever heard. Ah sat there and closed ma eyes.

The author not only knows her language, not only knows love, not only loves her characters --- but, as all good authors writing about Eastern religion must --- she knows her Buddhism, knows how to place it in the context of a normal family, one that is practically destroyed by the supposedly benign world of Tibetan masters.

Thus, Buddhism becomes a counterpoint to the story of Liz and Anna Marie and Jimmy, as fine as counterpoint in a Bach cantata --- the bass line going one way, the tenor another, the alto a third: all put together in a musical whole that can make one shiver with the glory of it.

A couple of times in the past we've bemoaned the fact that we don't have stars hanging around RALPH so we can pin them on a worthy writer (except for the single stars that appear on our General Index page). Buddha Da would probably garner the full monty. Big ones. Of gold. Shimmering there, right at the top, right where they belong.

Go to a reading

from this bookGo to the complete

review

Living Everyday Zen

Charlotte Joko Beck

(Sounds True)Zen is elegant, "elegance is refusal." "Use concentration in the service of awareness," she says. "Listen to the traffic," The traffic, the wind in the trees, the sounds from outside.She cites the priest Anthony Demillo, who said that we should view all people as mean, vicious, untrustworthy and manipulative. "And innocent. And blameless."

Zen is a "returning to silence." It is the practice of dying to the self. When you seek something, seek it over years, and finally get it (a new car, a house, a million dollars) the question should be, "And then what?"

§ § § This is powerful stuff. I have been here for an hour trying to boil her words down, but her words are already concise and to the point. So I give up.

If you have an interest in Zen Buddhism, or in merely shutting up the mind-babble, it is worth your while to listen to Joko Beck. She is elegant, avoids stuff and nonsense. "True nature is no nature," she says. "Our core beliefs make us slaves," she says. "Practice is austere," she says. If we are living "caught up in our fears," we are not living.

It is the pretend excitement of our thoughts that catches us every time. But thoughts and passions and prejudices and hates and angers just aren't worth it.

They will pass.

Listen to the traffic, not the sirens.

Go to the complete

reviewOut of Your Mind

Essential Listening from the

Alan Watts Audio Workshop

(Sounds True)Alan Watt's program was called "Way Beyond the West," and it was aired every Sunday night --- the closest thing to Pacifica's religious program. Most often it was on tape, a half-hour of musing, very amusing musing, on Zen, Buddhism, psychology, etymology, eastern culture, Christianity, Hinduism, morals, Japanese thought, Indian history, American vagaries, Tibetan lamas, the role of the roshi, the stages of world culture, the meaning (and joining) of divine opposites, the Baghavad-Gita, the Kama Sutra, the Book of the T'ao.Watts spoke with an elegant accent, seemed to know everything there was to know about Eastern religion and thought. And he loved paradox. "There is a famous koan about a young Buddhist student sitting at Zazen," he would tell his rapt audience (me!): "The roshi comes along and asks the young monk what he is doing.

"'I am meditating so I can become the Buddha."

"The roshi picked up a brick that was lying nearby. 'Can you make a mirror out of this brick?' he asked the student.

"'No.'

"'In the same way, you will never become enlightened by meditating,' said the master.

"This koan is not very popular in present-day Japan," said Watts, smiling, at the microphone (and me, me pretending not to be charmed out of my wits, listening to my new, perfectly spoken master guru).

Go to the complete

reviewAmbivalent Zen

Lawrence Shainberg

(Pantheon Books)One of the constraints of Zen and other spiritual practices is that few people can take seven days off from work without at least giving up vacation time, and fewer still would choose to spend their vacations staring at a wall. Since family life is another constraint, the preponderance of students are single, widowed or divorced, and most of the couples are childless or old enough that their children have left home. Given the fact that loneliness and psychological desperation are two of the best catalysts for practice, one of the largest contingents around Zen or other spiritual centers will often be drawn from the recently divorced."We've got this idea of something trapped that we've got to set free. Like there's a bird in your hand, and what Zen is about is spreading your fingers and letting it fly away. Whoosh! I'm enlightened! But you and the bird are the same! You and your hand are the same! Nothing needs to be opened! Nothing needs to fly away! Realize this and you've automatically let go! "

These words are delivered in the course of a teisho on my old favorite, the koan about the flag and the wind from The Mumonkan. Glassman offers us a perfect example of letting go by taking it forward in time and turning it on its head. "Two hundred years after this event occurred, seventeen monks, taking refuge at an inn while on a pilgrimage, were caught in an earnest discussion of it. 'Which is moving-the flag or the wind? It is not the wind that moves; it is not the flag that moves. It is the mind that moves!' As it happened, the old lady serving them dinner was an enlightened being. After eavesdropping on their debate for some time, she could not contain her impatience with them. 'You fools!' she shouted. 'Don't you understand? It is not the wind that moves; it is not the flag that moves; and it is not the mind that moves!' At this point --- a world record, for sure --- all seventeen monks were enlightened."

Go to the complete

review