We Were Brothers

Barry Moser

(Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill)

There is one crapshoot in life that will always get you in the end . . . and it ain't being played out in the casinos of Las Vegas. It's the roll of dice that occurs nightly in the bedrooms of all --- rich, poor, good, bad, saints, villains, kings, presidents and the guy who serves you sausages at the local deli.The Big Roll, the hottest of them all, the Zygote Sweepstakes: where ovum and tadpole meet, causing a minor explosion of heat and light that starts us on the dicey up-hill and down-dale ride on the roller-coaster we so winsomely call Life.

And you and I have no say-so in the matter. The most crucial event of our next six or eight decades (if we are lucky) --- the conjoining that determines where you will live for the next childhood, and with whom, and whether you will be eating or starving, whether you will get beaten daily or a buss (or both), whether you'll be handsome and loveable (and loved), or even turn up as the Ugly Duckling, all about you laughing at you, as you judder along down the road, with your walrus-neck and lordosis, all the kids around you mocking your chances to make it through this vale with the least agony.

There it is, and it's going on at this very moment, all over, under the aegis of the one Faulkner called "the dark diceman," determining without a single consultation with you the color of your skin, the color of your eyes, the shape of your body, long, short, fat, tall, twisted, bunched-up, distinguished, ratty --- along with coming onslaughts of health (and ill-health), and charm (or charmlessness), and fun (or dyspepsia), and believing (or disbelieving), and the ultimate discrimination: whether you'll be an innie or an outtie down there in the weenie department.

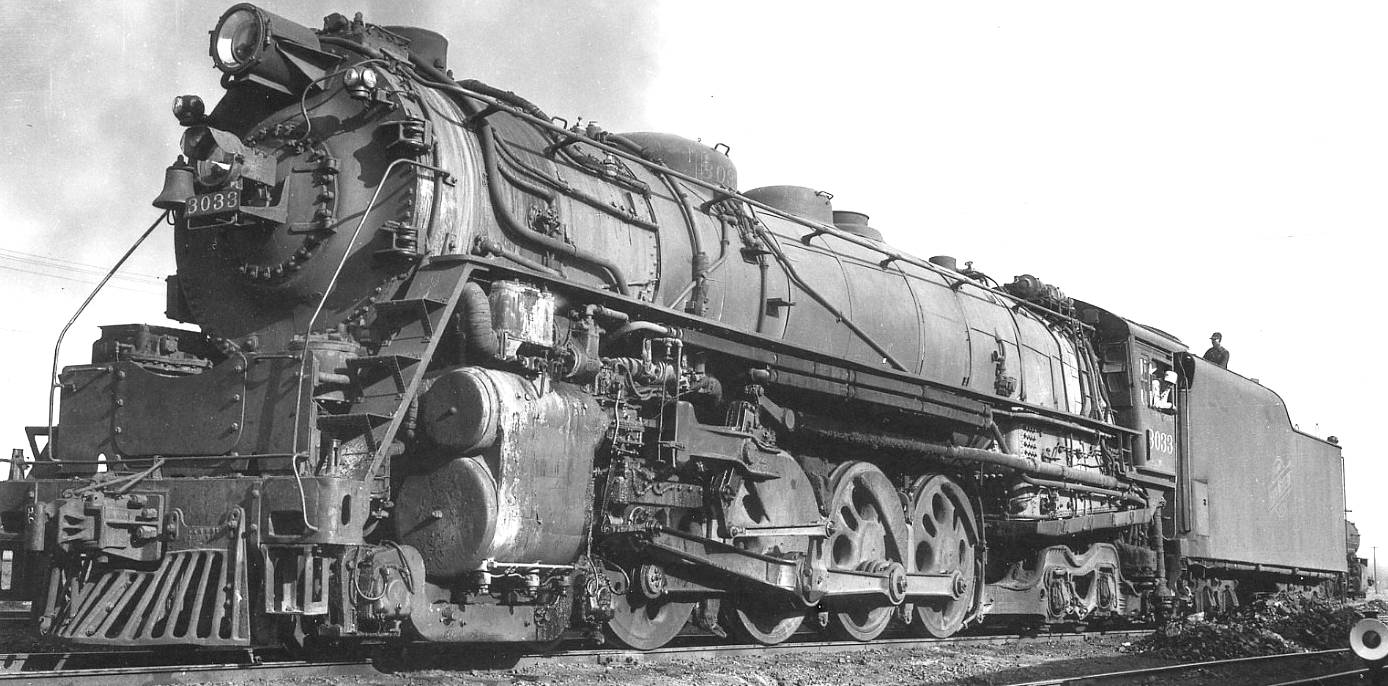

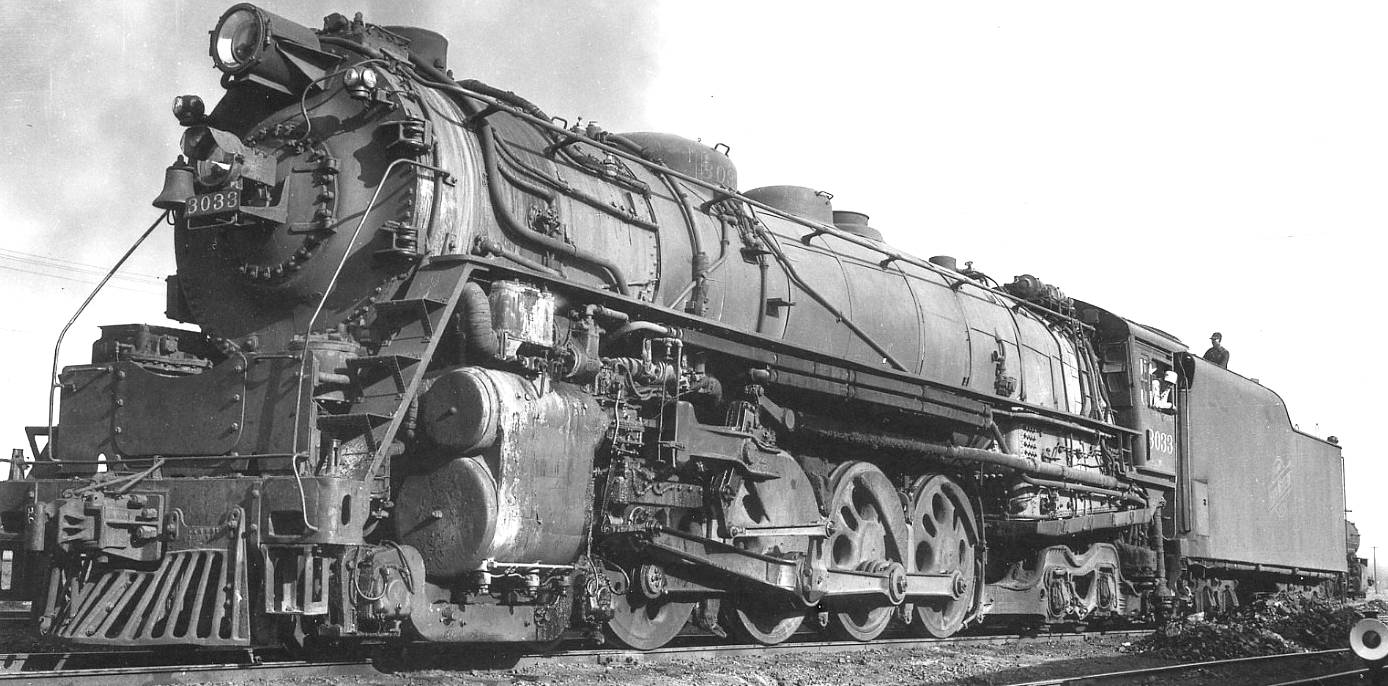

And so it falls, and so it fell to Barry Moser when that genetic roll took place that he would be the child of a rich 300-pound Tennessee gambler (who was to die within the year), a sweet but unpushy mum, and a ultra-neat ultra-angry brother, there just outside that famous railroad junction whose poetic name was glued sixty years ago into a song made famous by Glenn Miller, namely "the Chattonooga Choo-choo."***

They lived at at number 509 Shallowford Road with mother Wilhelmina. After the death of Arthur Moser, Wilhelmina married a "sporting man" (hunting, fishing, guns, boats, golf) who would be step-father to the Barry, the author of this book; and Tommy, definitely not the author of this book. And we learn in We Were Brothers that the dice thrown turned them against each other (and against themselves) very early on, that Barry thought and still thinks he got shafted by the gods by being stuck with a brother who seemed to loathe him.

Barry comes on as very reserved to his mother and step-father. His main loathing is saved up for his brother and his home because he despises the south of his birth, so many aspects of it, most of all, its searing interracial complexities. He left early for The North, the intellectual hot-spot for all us would-be Artists.

As an illustrator, Barry has come to be rather famous in his dotage, teaching at Smith, illustrating an edition of the King James Bible, being acclaimed. Tommy went on to stay in the south, cadging his pay, working for every penny (and, despite a severe case of dyslexia, graduating from Baylor), living a life stolidly apart from Barry. Tommy recently died, an unknown but successful businessman. His post-mortem is dictated by the survivor.

§ § §

Barry and his brother Tommy, unhappy campers, taking their mutual frustrations out on each other. Slamming, punching, hitting, yelling, breaking teeth, noses, in one case, wrestling, destroying --- in one case --- much of their home. One of the liveliest passages in the book is this classic battle. How did it start? A question of who was going to wash the dog. Get that: a life-threatening battle over who is going to scrub poor innocent Old Dog Trey.

"He hit me." "I tackled him, and the fight was on." These are two brothers, presumably both in high school, who have lived together for years.

The altercation migrated from my bedroom into the back hallway, through the kitchen, across the dining room, and was in full tilt in the living room when Mother came home.

When she came in and saw her dining room chairs overturned, the living room floor lamp in pieces on the floor, the door leading to the hallway broken, and a hole in the living room wall. She screamed and pleaded for us to stop. We would not.

Finally she has to call the police to come and stop the fight. "The presence of a policeman in our living room was enough to make us stop our brawl" Evidently, the idea of spending time in a Chattagoona's Gray-Bar Hotel was enough to close down this classic tiff. But it was almost was the last one. And the final zinger: Barry breaks Tommy's nose; thus winning. What?

In the trade, this is called a "dysfunctional family."

I know: there is nothing that says that we have to love our siblings. Many's the family where family hates go underground, last for many years. Barry claims now to have loved Tommy, but admits to contributing to the strife between them. "It just took too long for us to understand it. To admit it. And try to do something about it."

What the reader ends up with is an extended exegesis on Tommy being a racist growing up in WWII Tennessee, Barry in contrast implies that in regard to race, he is superior. And what we see is that Barry doesn't even for a moment see that his brother's taunts about race are just smoke-screen, a convenient flag, that old let-me-piss-you-off the easiest way I can. Barry never learned, as well, that one of the sacred laws of family peace is that you leave race and politics out of all intra-familial dialogues. All. Families are the last --- and least willing --- to be changed. I grew up in the south too --- the deep south of the 30s, 40s and 50s, and you don't want to hear about the truth of my own family's views on blacks, Jews, Mexicans, or the IMF.

All told, I see We Were Brothers as mostly a self-justification, and a made-up story of a human being that Barry is unable to picture (even though he is an illustrator by trade); one who is just like him.

In December of 1997, he sent a letter to Tommy, a snotty letter which --- as printed here --- even pisses me off (although it did manage to wake me up as I was nodding out there towards the end of We Were Brothers.) It starts with a family business call where they get into some old arguments, and Tommy uses the N-word. After a few shouts to clear the air, they both hang up in a fit.

The author immediately sends Tommy a letter telling him not to call "until you can act like something other than an ignorant fucking redneck." He then tells him "I am close friends with many of the finest southern writers, educators and journalists," and that none of them use that word.

Tommy's ripost is a classic, leaving the reader with the feeling that the author might have been better served if he had just stood in bed. It says, briefly, that his life was a pain too, and that Barry might be a little more open to what he went through, too. In brief, it is a little classic of honesty and openness.

It's a little late for family therapy (Tommy's gone off to the dysfunctional family institute in the sky) and Barry has, we hope, not passed his own family poison onto other friends and relations.

The moral of it all is a good one, though:

- There ain't no accounting for the people we'll wake up post-uterine to find ourselves saddled with;

- Make the best of it while you can until you can bail out; and

- Never ever write a book about it --- especially one that is so loaded that (you think) you are going to come out the winner in an unwinnable life-long inter-familial dispute. The odds are all against it.

***Pardon me boy, is that the Chattanooga Choo Choo?

(Yes yes, track 29)

Boy, you can give me a shine

(Can you afford to board Chattanooga Choo Choo?)I've got my fare

(And just a trifle to spare)You leave the Pennsylvania station 'bout a quarter to four

Read a magazine and then you're in Baltimore

Dinner in the diner, nothing could be finer

(Then to have your ham and eggs in Carolina)When you hear the whistle blowin' eight to the bar

Then you know that Tennessee is not very far

Shovel all the coal in, gotta keep it rollin'

(Whoo whoo, Chattanooga, there you are)There's gonna be a certain party at the station

Satin and Lace, I used to call funny face

She's gonna cry until I tell her that I'll never roam

(So Chattanooga Choo Choo)Won't you choo choo me home

(Chattanooga, Chattanooga)

Get aboard

(Chattanooga, Chattanooga)

All aboard

(Chattanooga, Chattanooga)Chattanooga Choo Choo

Won't you choo choo me home

Chattanooga Choo Choo