A Contrarian Philosopher in East Berlin

At night I went to work in the light bulb factory again. I was working off my portion of the debts that Alex [her husband] had incurred from his used cars. I thought that if I helped to pay off the debts, I could also clear away some of the guilt I felt towards him.My relations with the other women who worked on the assembly line were good. Our collegiality expressed itself by agreeing not to work faster than was necessary, by organizing smoking breaks, and --- whenever a conveyor belt broke down again or there weren't any bulbs to pack --- by playing skat or poker for a tenth of a cent per point to pass the time. We also all agreed that we could take for ourselves as many of the people's light bulbs as we needed, thereby putting into practice the principle "from each according to their ability, to each according to their need."

One day I arrived for my so-called "presence day" at the Academy bleary-eyed from the night shift. A colloquium on the topic of "alienated work" had been scheduled. The breakfast that I had eaten in the factory canteen --- scrambled eggs with bacon --- lay heavy in my stomach. And my colleague was explaining, with considerable philosophical effort, that objectively there could not be any alienation under socialism. I played with the idea of saying that I had just come from the night shift and still heard the sound of alienated work. But I restrained myself and, well-behaved, proposed that within the context of a solidarity action we should arrange to work either a night or a day shift at the Narva light bulb factory and then donate our earnings. By working at the factory itself, we could see whether the activity was alienating or not.

Some of my colleagues were unsure if I was making fools of them, for no one here knew that I spent my nights at Narva. The colleague giving the lecture on the topic was the first to regain his composure and told me that I could not combine theory and practice so mechanically. I did not say anything more and tuned out. In my head, the differences between the night and the day shifts were dissolving into dance steps that lacked a libretto. My notebook from that period was full of such dance steps and figures for a ballet in which I wanted to bring together what stood separately by itself: assembly-line work and "pure reason."

After a little more than a year, I had worked off my portion of the debt for the used cars that Alex had bought. Money was now coming regularly into my chequing account, so I could discontinue my night shifts at the light bulb factory.

Since I could not get the dance steps and the idea of a libretto out of my head, I often attended the ballet rehearsals at the Komische Oper in the mornings of my "presence days." I soon realized that the presence days at the Academy were a formality. It sufficed to put your briefcase down on time in the morning, spread out some reference books on the table, and say that you were going to the library and would be back by lunch at the latest. Since, with six philosophers of history sharing an office, no one could consider working at the Academy anyway, it was enough if one person stayed there who could say, if asked, that the others were away tending to this or that matter. This was necessary because, at irregular intervals, the Institute administration conducted attendance checks. This was a bit reminiscent of school, and so the coworkers behaved accordingly. One person covered for everyone else.

In this way it was possible, within certain limits, for the individual staff members to organize their presence days at the Institute for Philosophy as they saw fit. Some went shopping, others in fact went to the library or to a café. I went to Café Espresso, where half the Institute congregated on the presence days, or I went to the rehearsals at the Kornische Oper. It was right in the neighbourhood. There I learned about the Young Dancers group (Junge Tänzer), and applied to join. For years during my other, musical life, I had also had ballet lessons. That would be enough for the group dance if I practised regularly.

At some point, I naïvely asked to be excused from a Party meeting because the ballet rehearsal was about to begin --- and was not allowed to leave. The Party secretary then confronted me, in all seriousness, with the choice: either dance or become a philosopher. The two were not compatible with one another. I tried to explain that Marx himself had spoken about how, among other things, free existence consisted in being able to go fishing in the morning, till the fields at midday, and pursue philosophical criticism in the evening. Since my comments were interpreted as politically immature, I sought out a politically more mature excuse for the next time.

During this period, I came up with the idea of transforming Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit into a ballet. I searched the text for potential dance steps and found them too. I preferred to work on my libretto during the Institute's endless meetings. Since we had a lot of meetings, the ballet was taking shape nicely until one afternoon. I was abruptly pulled from my daydream and the yawning boredom changed suddenly and unexpectedly into a drama. Three Furies, dressed as politicians, were pulling to pieces the man who, along with my pastor, served as the Institute's co-director. Even I knew that this other co-director was the real head of the Institute, but at the time I did not want to know anything more, partly because I got on well with my former pastor. As I later learned, these crazed women had been charged by the SED district leadership to bring down the real head of the Institute. Their performance was staged.

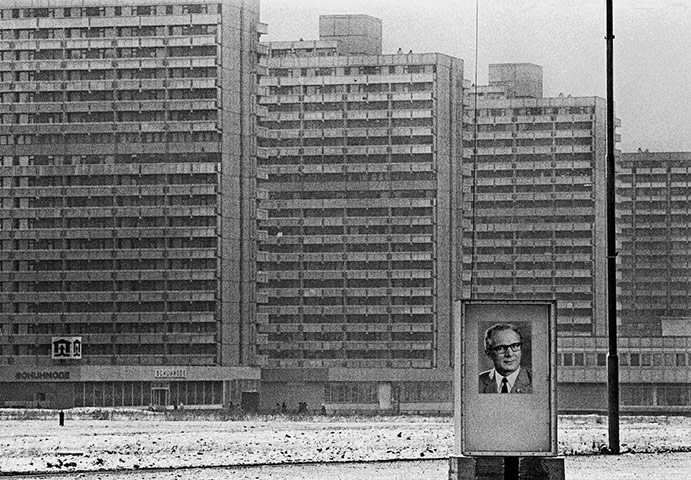

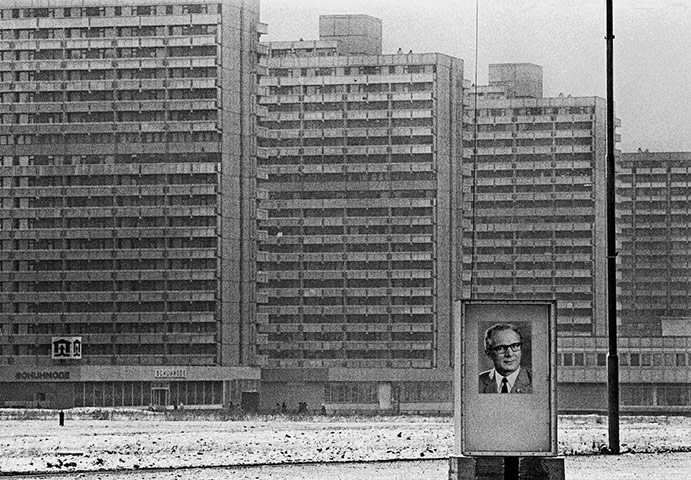

Before long, a hysterical lynching mood developed that was so disgusting that there was hardly any air left to breathe. The meeting lasted more than seven hours. When it was through, I walked the streets for hours and howled about all the malicious behaviour. At some point, I began picking a giant bouquet of fall flowers from the city's flowerbeds. That calmed me. The bouquet was very beautiful. I looked up the Institute director's address in a phone booth, walked to Alexanderplatz, and rang his doorbell. He opened the door himself. Without saying a word, I handed him the bouquet. Without saying a word, he invited me into the kitchen and made me a cup of cocoa, on which I warmed my hands. Only then did I notice that I was freezing. He laid a blanket over me and sat down. Everything transpired without us ever saying a word. We sat at the kitchen table until it got light out outside. Then he called a taxi and said that it would probably be better now if l slept for a few hours.

From that evening, a deep sense of understanding joined us in a silence that we absolutely wanted to preserve. It had something to do with an admission of helplessness. There was a language underneath language that we had found together. We both knew that this silence was unique and for that reason we never got any closer to one another. This silence protected me at the Academy in the coming years. For, having surviving the power play, he later became the sole, commanding director, indeed one of the most feared directors of all time at the Academy of Sciences. He was one of the most intelligent and sophisticated intriguers that I ever met in East Germany. But he always kept me out of everything. Whereas he soon demanded that all other staff members submit unconditionally to his policies for the Institute, he only demanded from me this distance in which the silence of that night at the kitchen table recovered its sound.

--- From Wall Flower:

A Life on the German Border

Rita Kuczynski

Translated by Anthony J. Steinhoff

© 2015 University of Toronto Press