The Music of Gold

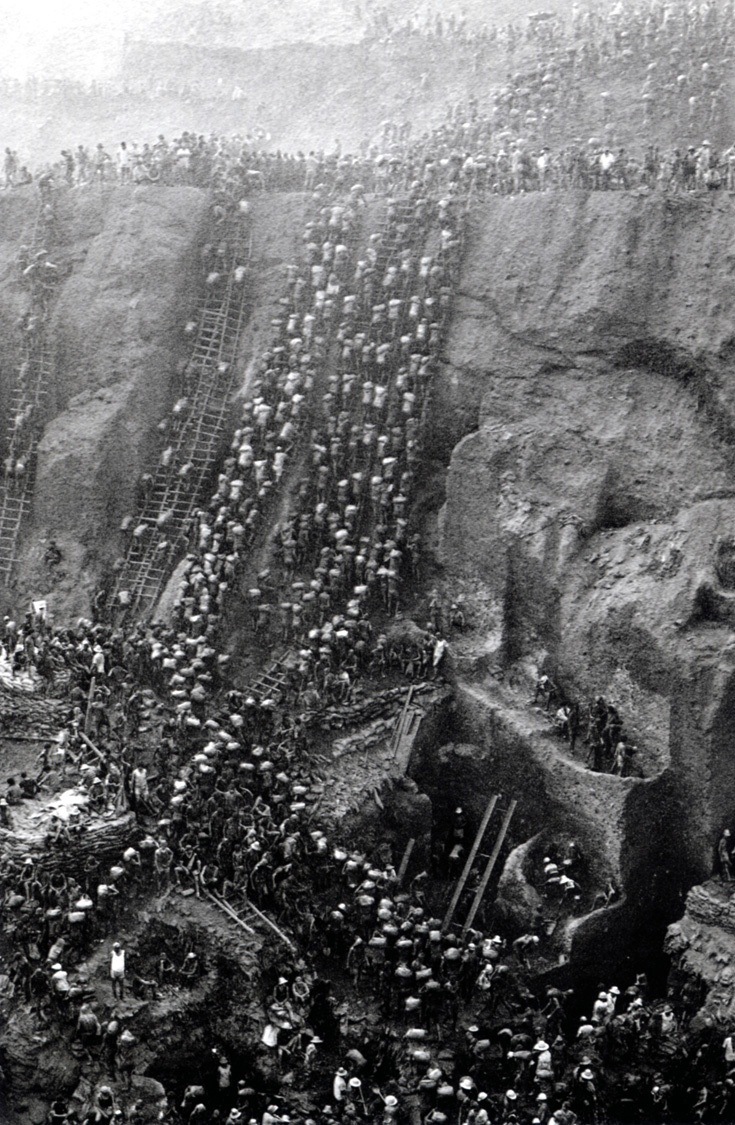

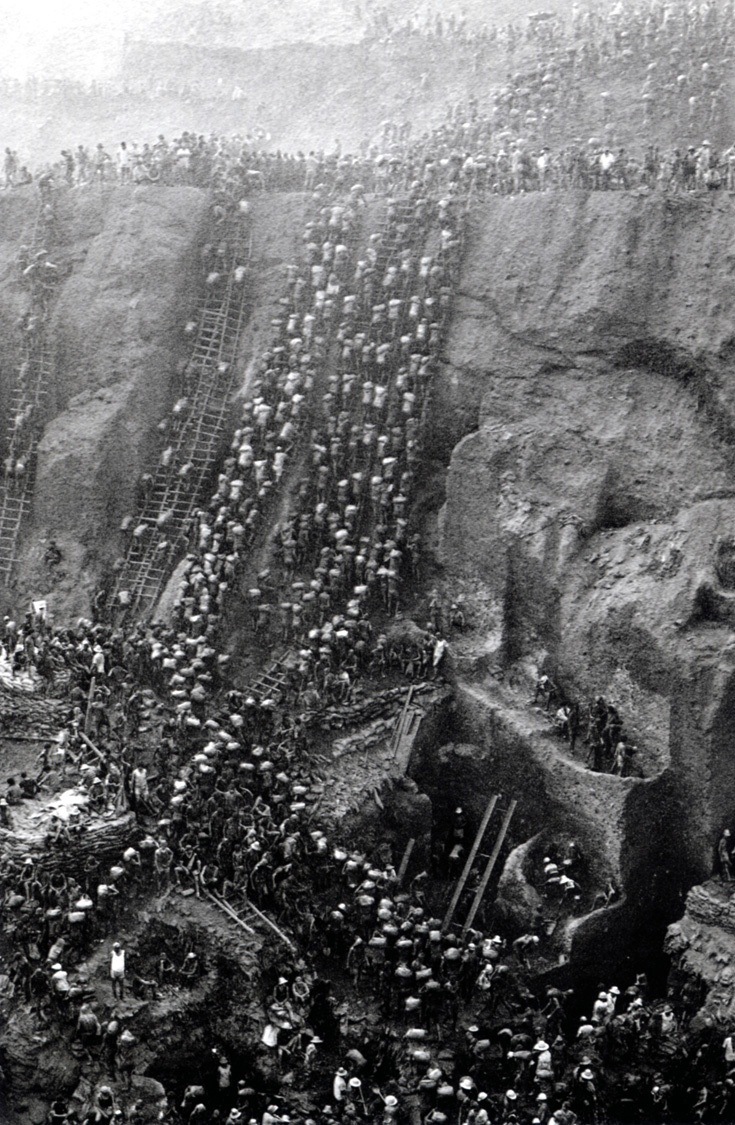

Some of my proposals, according to traditional filmmaking practices, were really radical. Powaqqatsi, the second film in the trilogy, begins in the Serra Pelada gold mine in northern Brazil. Godfrey had some film footage previously shot by Jacques Cousteau. Using that as a reference, I composed a short ten-minute piece of highly rhythmic music for brass and percussion. Then I traveled with Godfrey and his film crew to Brazil to Serra Pelada itself, an open-pit gold mine that at its high point had ten thousand miners working side by side. By the time we arrived in 1986, it was down to about four thousand miners.This was quite a bizarre place. It could easily have been mistaken for a prison set in a jungle, but in fact it was a startling display of capitalism at work. Every man there was an owner of part of a six-by-nine-foot plot. They all belonged to the cooperativo and, though there were soldiers and wire fences all around the site, the miners were, in fact, all owners of the mine. When we got there, Godfrey immediately began walking down into the pit, a huge crater that was the work of six or seven years of miners digging straight down into the earth. When we got to the bottom, we just sat down and watched the men digging and hauling bags of earth up bamboo ladders to the surface. Once there, they would dump the earth into a large wooden sluice that was fed by a rivulet of water from a nearby stream. The water carried away the dirt, leaving behind gold nuggets.

I had been traveling to Brazil for several years for a winter composing retreat in Rio de Janeiro and could manage to speak Portuguese reasonably well with the workers. Down below I talked to the men. They were consumed by gold fever. I had never before seen anything like it. Moreover, I realized how young they really were. I guess none was older than his early twenties and some were younger still.

"Hey man, what are you doing here?" I asked.

"We're here finding gold."

"Where is it?"

"There's gold everywhere, all over here,"

"I've been finding a few nuggets. But when I get a good big one, I'll cash it in and go home." In fact, there was a Banco de Brasil at the top. right next to the pit.

"Where are you from?"

"A small town near Belém" (275 miles to the north).

"And what will you do when you get home?"

"I'll either open a restaurant with my family or maybe buy a VW dealership and sell cars."

What they really did, when they found a nugget --- the nugget could be worth five or six thousand dollars --- was to sell it to the bank, take a plane to Manaus, and in one weekend, spend all the money. Then they would come back to work. There was one fellow who had a little restaurant there, just a tent and some tables and a fire. He said, "I don't know what I'm doing making food here. This place is probably right over gold. I could dig right down here and find gold."

The people there were obsessed with gold. They were convinced they were going to make a fortune, and some of them did, but they also spent it. Every morning when you woke up and walked outside, you saw a line of men in front of the Banco de Brasil, trading gold dust for cruzeiros, the Brazilian currency at that time. They were making money every day.

A little while later Godfrey and I climbed up the bamboo ladders to the surface. It was a good five hundred feet up and the ladders were only about twenty feet long. When you came to a ledge cut into the wall, you had to change over to another ladder, and once you got in the line moving up there was no stopping --- the men behind you just pushed right on up. They were thirty years younger than us --- tough, strong, and in a hurry.

We began filming that afternoon. The music I composed was on a cassette and Leo Zoudoumis, our cinematographer. was set up with headphones to hear it on a Walkman while he was filming. The filming got started and went on for a while. Finally, one of the miners noticed the headphones and asked, "What are you listening to?"

"The music is for here. You want to hear it?"

Of course they did, and, for a while, the Walkman and headphones were passed among the small circle that had formed around us.

"Muito bom! Muito bom!" --- "Very good!" --- was always the response.

The music for Serra Pelada is driven by highly percussive drumming. By this time I had listened to the baterias (drummers) in Rio de Janeiro often during Carnaval, where you would hear two or three hundred players playing different drums in synchronization with one another. It was a tremendously powerful sound. If you were lucky, and you were sitting in the right place, it would take eight or ten minutes for that group of people to parade past you, and you would hear nothing but this drumming. There were some cross-rhythms, maybe some twos against threes, threes against fours, but most of it was just straight-on drumming that you hear in a marching band, except that it was like a marching band on steroids. It was really loud and fast and that's what I put into the score, along with shrill, strident whistles that fit in perfectly in that piece.

When I came back to New York, I played this music for some of the people working on the film. They watched the footage, and they were shocked.

"Is that the right music?" they asked.

"Yes, it's the right music."

"But is that what it was like for those people?"

I said to one of them, "Did you think I should have done a piece like 'Yo-ho-heave-ho'? Is that what you think was going on there?"

Later, when I was actually making the film score, I added the voices of a children's choir to the brass and percussion already there, in order to capture the childlike energy and enthusiasm of the miners. To me, they were children, and I wanted to evoke that feeling with the children's choir in the score. That became a memorable musical moment.

--- From Words without Music

Philip Glass

©2015 Liveright