The Last Few Months

Best of The Year list that you'll read is

that we try to seek out the rare and abused ---

books that were mostly ignored by the dabblers

who abound in the U. S. Publishing Book Review Biz.

Some of the titles here have drifted about in the slough too long,

bumped around in semi-dark obscurity until a few

magazines and newspapers rescued them, helped us find them.

'Til the Well Runs Dry

A Novel

Lauren Francis-Sharma

(Henry Holt)

She's feisty and funny, comes off like a Trinidadian Moll Flanders or calaloo Molly Bloom --- filled with spikes and smarts and all kinds of survival mechanisms for her and the four kids that Farouk manages to plant on her.The Well is crammed with the worst of the worst of Trinidad or anywhere else: rape, incest, drugs, evil police, evil politicians, witches, spells, mud dust dirt heat, nasty parents and in-laws, snarky businessmen. And yet . . . and yet . . . with Marcia and Farouk and the kids we get to lead a rich hot tropical life, funny, too . . . sometimes heart-stopping, in each of these short chapters, packed with intrigue, tension, all at perfect pitch.

Someone is always moiling with someone else; Farouk is being stupid again; Marcia saying never again with him --- and yet she can't stay away from him. Why, we ask ourselves, does she continue to want to be with this ninny?

Just know that Francis-Sharma knows how to serve up a dandy plot, as rambly as it is, and she's able to find comedy when everything's the worst of the worst.

And in the best, too.

Need I say can't-put-it-down?

Go to the complete

review§ § § Blind Moon Alley

John Florio

(Seventh Street Books)The story of Blood Moon Alley is all over the court, but the pace is exquisite and, at times, the prose sings as it should when you're mixing murder, crooked cops, casual 1930s law-breaking, prostitution, bathtub gin and naked down-home prejudice. This is Leo going to Chester's Chicken Shack, a taxi-dance hall "where Philadelphia's loneliest misfits pony up ten cents to dance with a fallen angel."The guy at the door gives him the once-over: "He's obviously confused at what he sees and I don't blame him. Chester's attracts just about every misfit in Philly, but not a lot of sweaty, chapped albinos with faint yellow haloes under the eyes." At the bar, he orders an "Aunt Roberta." The bartender "shrugs his shoulders, pulls the absinthe, brandy, gin, vodka, and blackberry liqueur, and mixes up a beauty."

Then he slides it to me with an apologetic look on his face. I take a pull and it's exactly what I expected --- slightly nauseating but strong as a steam engine. I swear they could use these things to power street lamps.

Go to the complete

review§ § § Hummingbirds

Ronald Orenstein

(Firefly Books)The most minuscule of the species is the bee hummingbird, weighing in at .06 ounces, no larger than 2½ inches.The largest hummingbird is the Patagona gigas of Chile, ten times larger than the bee. This "giant" hummingbird is nine inches long, and weighs as much as .8 oz, but, outside of sheer weight, it is a dull-bulb, a true bomb. Its coloration has been described by a leading ornothologist as "boring." Supporters of the giant hummingbird have banded together to taunt these experts, lambasting them with constant twitters and larding them with meager if insulting droppings.

Still, there may be a brighter day for the patagona, because its days as the hummingbird gargantua may soon be over. This change has been brought about through studies of the common ruby-throat. Because of its extensive range, we've learned that it has to store up energy as fat . . . almost doubling its weight. This fact has led to the recent success of Japanese scientists to selectively produce ever-larger hummingbirds. By inbreeding, conjoined with Jack LaLanne-type exercise programs, ornithologists at Kobe University have recently created our first 65-pound hummingbird.

Named Tubby the Terrible for his phenomenal girth (and miserable disposition), this fugitive from the gland gang can, unfortunately, no longer twitter, but merely groan. However, Tub uses his weight to get what he wants. When he spots another male hummingbird trying to pinch his poke, he sits on the sucker until he cries uncle.

Go to the complete

Go to the complete

review§ § §

My Depression

A Picture Book

Elizabeth Swados

(Seven Stories)Depression? Swados' friends offer such comforting thoughts as, "Look at the people with AIDS. They really need medical research and attention," and "My father came over from Latvia with nothing. Could he go to a psychiatrist? No!" And my own personal favorite, offered as help to me by one of my friends when I was at the apogee: "Why don't you just stop being so self-indulgent. Jesus!"I would never poo-poo Swados comic book, for it shares with Art Spiegelman's Maus and R. Crumb's Why Bother? making a bizarre joining, the built-in contradiction of a depressing message stuck in one of the most comic forms, a 21st century Falstaff, Hamlet turning up as a late-night episode in Saturday Night Live.

Swados' big message towards the end here might be the best . . . if you're still around to get it. That is, you've had it, you've done it. Now you know that your worst horror doesn't have to be realized.

You may have thought the black dog would never go away and just leave you alone. But you were wrong. It did seem to take forever, but now it's done with you.

It may blow into town again, sometime, but you've done it once now and survived and you'll probably survive the next one, too. And when it comes bounding back, you'll know it is possible to outlast it without doing personal harm to you and your loved ones.

And, then, you begin to think: what a nasty message, no?

For the chances are high that the dark bastard will return.

What then?

Go to the complete

Go to the complete

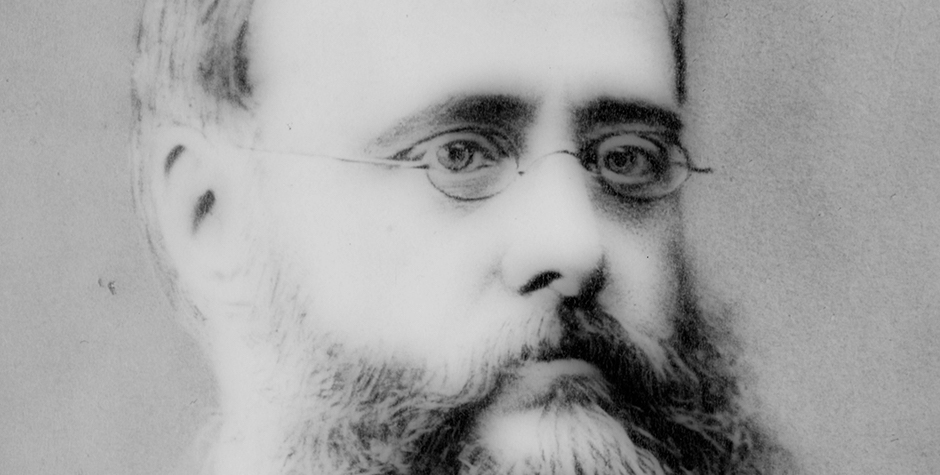

review§ § § The Small House at Allington

Anthony Trollope

Read by David Shaw-Parker

(Naxos Audiobooks)The Small House at Allington in the original Oxford University Press edition runs to almost 700 pages. The spoken word version here runs to 20 discs, lasting almost twenty-six hours. This is Trollope's fifth of the six Chronicles of Barsetshire.He wrote dozens of novels in all, setting us to wonder when he had time to sleep, much less eat: he was somewhat roly-poly, loved his mutton, venison, beeves, chyne, snipe and pease soup. We may also wonder how he had time to gad about all over much of England during his many years as a postal surveyor's clerk in County Offaly, Ireland (where he took up fox-hunting, of all things); then go off to Scotland, Egypt, Malta, Gibraltar and India to reorganize various colonial post-office services, to make them more efficient. He was what we would now call a business consultant, and he was a talented and valued one.

How did he do all this, and at the same time, polish off forty-seven novels, much less write eighteen non-fiction books, essays and articles on various subjects, accompanied by long letters to friends and fans, plus, my god, two plays?

And, mind you, novels, some of them ok, some fine . . . a few of them great. I include in that last The Small House at Allington. I am not alone. Critics call it one of the best of his output, and Wikipedia tells us that "It enjoyed a revival in popularity in the early 1990s when the British prime minister, John Major, declared it as his favourite book." Perhaps one of his best decisions during his six years in office was to boost the sales of this terrific novel.

I have stuck with The Small House at Allington in sickness and in health, in good times and lean --- no mutton for me, thanks: and I wouldn't have missed it for the world. I worked my way through it twice: first, listening to it on disc, narrated by David Shaw-Parker; then, by going through parts of it in the Oxford University Press volume.

As often happens with a sterling novel on disc, in my tri-weekly commute, I would find myself driving to my destination and then sitting there like an idiot in the car, not willing to get out, stuck there by the sheer narrative force of Trollope and in this case, this elegant and opulent reading by Shaw-Parker. He's a narrator who's all over the place, at home with any of the many accents and asides that constitute the class and social diversity of 19th century England.

Go to the complete

review§ § § The Wright Brothers

David McCullough

(Simon & Schuster)At the end of this page-turner, the things we are left with are how the ever-steady Wilbur, and the slightly more lubricious brother Orville worked together, talked together, thought together, learned together, were almost Siamese in their need and ability to be as one. They were brothers that you and I may envy, two who were always comfortable with each other, who debated and elucidated and conceived their great baby together, the one that soon enough would soar.In the face of so many disbelievers, how could this salt-of-the-earth pair out of the rural backwashes of Ohio come up with the answer to a dilemma that had baffled so many for so long, one that caused one of their friends to write,

When you see one of these graceful crafts sailing over your head, and possibly over your home, as I expect you will in the near future, see if you don't agree with me that the flying machine is one of God's most gracious and precious gifts.

A final surprise that McCullough leaves us with, one that, at least for me, was the least expected . . . was a longing to somehow fly back to the time in which these brothers lived. This sentiment comes partly from the dozens of black-and-white photographs here filled with the air of early 1900's America constructed by the author.

Hawthorne Street, in Dayton, with the plane trees in bloom in the spring, the house --- a simple unprepossessing Victorian frame house at #7 --- reworked by the brothers.

It was a clean, orderly place, in a clean orderly city, in a clean orderly world (no fret-filled catastrophes in the Middle East;, no massive bombs sitting, waiting, a finger on the button; and, thank god, no drones).

It was a world filled with an assumed innocent virtue, the mainstay of America in the early days of the 20th century. Dayton, Ohio, a provincial locale where two industrious young men just decided one day that they were going to solve a problem that had plagued humanity from the first day that the first man saw the first birds in flight.

How to do that?

How to soar?

How to go up without fear, pass over with pleasure, come down with surety, land with joy, and go home at ease.

After another fine day spent gliding about in the warm and ravening air.

Go to the complete

review§ § § Wondering Who You Are

A Memoir

Sonya Lea

(TinHouse Books)This is a manual on learning how to live with a new bear that just crept out of the the cave. It is also an object lesson on how to create a change, one that she must go through if she is to survive with a husband who has gone through tremendous changes.What does she learn, finally? Just exactly what the Buddha master and the Italian street people were trying to teach her. That Richard's memory loss may not be "such a bad thing." That perhaps her new husband, this wide-eyed innocent boy in a man's body, has something beautiful to teach her. Like how to love.

Not like before. Forget before. Bury that one. No: she must learn how to love this new "doofus," so different from the other; one who, completely differently, in his own gentle sweet way can enter her soul, sweep her off her feet . . . help her to become a bit of a doofus herself.

Years after the night Richard died to his former self, we are seated on stools at the Tractor Tavern, surrounded by beers, beards, plaids, braids, boys. I call him Buddha Bear, his secret label, his bedtime name. His hands reach for my bottom. Squeeze. A gesture hidden and overt, the perfect flirt. We lean into each other, starry with the song and the dusk and the delight of this time.

If I silence the obsessive longing that parades like a madcap clown in my mind, Richard is the perfect man for me. My husband shows me that the fundamental nature of being here --- on earth, in love, with the sexual experience --- is joyful As long as I know that in the midst of having anything, I don't get to keep it. Enjoying the ephemeral. This is the best definition of sex that I can imagine.

--- Lolita LarkGo to a

reading

from this book

§ § §

Like a Beggar

Ellen Bass

(Copper Canyon)She manages to show, with her faultless poetic muse, affection for things that might topple the rest of us into despair: noisy streets, getting fat, liquor stores, coming down with migraines, getting old, "frilled jellyfish," the diapers of our dying parents, doctors dressed in high heels, chicken shit, people who smoke, and onions --- at least, Pablo Neruda's onions.But I claim that this Bass is no pollyanna. She doesn't mind showing us what drives her to despair. Like the snow disappearing from Kilimanjaro, sea lions night after night "barking from the rocks," people killing people in Gaza, and those tedious folk who --- in their religious passion --- are willing to "burn you at the stake/or pry off your fingernails." Oh yes: and the damn birds, "singing like crazy in the morning."

Whistling and chirping, warbling, squawking,

claiming their territory, mine, mine, mine,

and calling for sex, pouring themselves,

into the blue bowl of morning.In my lights, a poet who is worth her salt should not sprinkle poetry around like a precious seed but dump it everywhere. Because all the world is poetry, and because good poetry is the world.

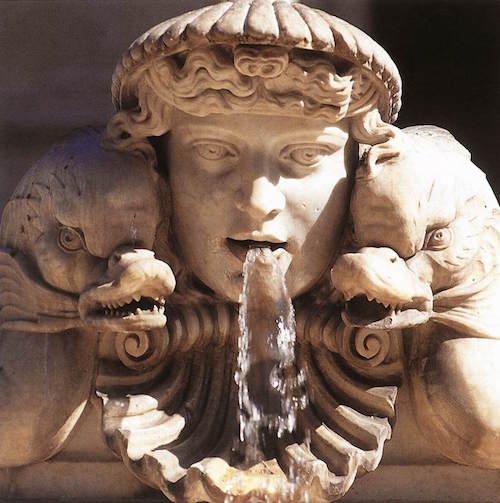

All parts of a poem must sing. The wasp with that breathless wasp waist, "shocking/how anything that slender/could conduct the business of life." Or a beautiful woman in Bakersfield:

Her cinnamon sheen, her gold dress

zipped tighter than the skin of a snake.

And her deep décolletage, exposed enough for open-heart surgery.

She's a yacht in a sea of rowboats.

An Italian fountain by Bernine.

She's the Statue of Liberty. The Hubble Telescope

that lets us gaze into the birth of galaxies.Go to the complete

review§ § § The Moonstone

A Romance

Wilkie Collins

Ronald Pickup et al,

Readers

(Naxos)I got all of this terrific story read aloud to me on the seventeen discs that came from Naxos, and thus got to hear it as most people did in England 1868 --- having it read aloud to the whole family, there before the fire, on a chilly evening in late winter, weeks after weeks after weeks.Only I was able to carry this spellbinder with me in the car, and so each of my commutes was changed into an intoxicating journey into upper-class England of a century-and-a-half ago, there at the family spread in Yorkshire, with all the extended Verinder family, with their many visitors, and the six or seven housemaids and gardeners, and the ever-faithful butler Betteredge who has been in the family for well over fifty years. Betteredge, who reads Robinson Crusoe as others would the Bible, and why not? For the complexities of the curse of the Moonstone demand exquisite details to unwind the why and the how of it, ways only grasped as we make our patient, toilsome way through what some claim to be the first detective story in the English language.

Wikipedia suggests,

The book is regarded by some as the precursor of the modern mystery novel and suspense novels. T. S. Eliot called it "the first, the longest, and the best of modern English detective novels in a genre invented by Collins and not by Poe." Dorothy L. Sayers called it "probably the very finest detective story ever written."

I hope I have given you enough interest to go find the book and read it --- or best of all, get this recorded version, allow yourself to be enraptured by Collins' words and by the nine readers who make up this album. Guaranteed: if you listen to the first disc, you'll be hooked.

But a warning: do not, repeat, do not read nor listen to a summary of The Moonstone, or look any place that will give you the slightest hint of the resolution.

I did so, half-way through the book, and I assure you that even one word --- and it is but a single word --- and the "detective fever" will be mostly lost to you, the unfolding story will be far less gripping, less entrancing, less sensational, less eye-popping.

Promise me you will avoid that fateful curse.

Go to the complete

review§ § §

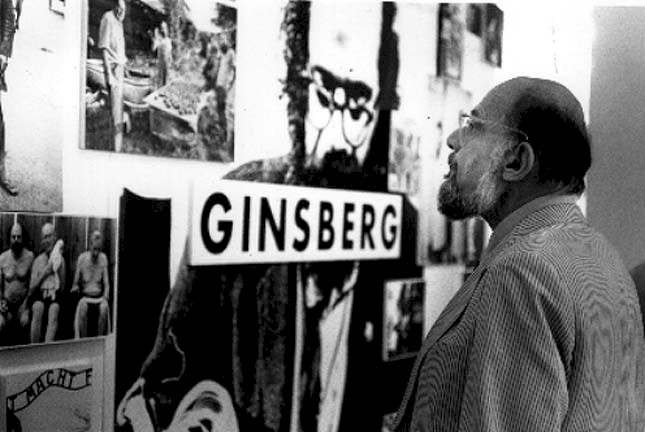

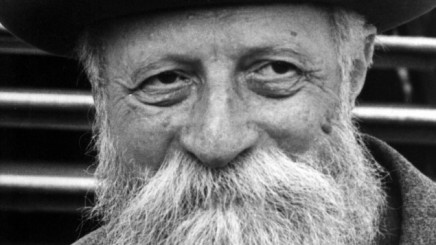

The Essential Ginsberg

Allen Ginsberg

Allen Ginsberg

Michael Schumacher, Editor

(Harper Perennial)Then there's the casual mention of the fact that he once went to interview Martin Buber. Just like that: "In Jerusalem, Peter and I went in to see him --- we called him up and made a date and had a long conversation. He had a beautiful white beard and was friendly; his nature was slightly austere but benevolent."Peter asked him what kind of visions he had and he described some he'd had in bed when he was younger. But he said he was not any longer interested in visions like that. The kind of visions he came up with were more like spiritualistic table-rappings. Ghosts coming into the room through his window, rather than big beautiful seraphic Blake images hitting him on the head.

"Melt into the universe, let us say --- Buber said that he was interested in man-to-man relationships, human-to-human --- that he thought it was a human universe that we were destined to inhabit.

"And he said, 'Mark my words, young man, in two years you will realise that I was right.'"

This was like a real terrific classical wise man's "Mark my words, young man, in several years you will realize that what I said was true!" Exclamation point.

And I am thinking that in 1961, Allen Ginsberg went with his lover to Jerusalem, and called up Martin Buber, and said he would like to come over and chat with him, and Buber said OK, and so the two of them went over to Buber's house, and they sat and talked with him, and Buber said, "Mark my words, young man." And he did and it was and it was true. And you read it here.

Go to the complete

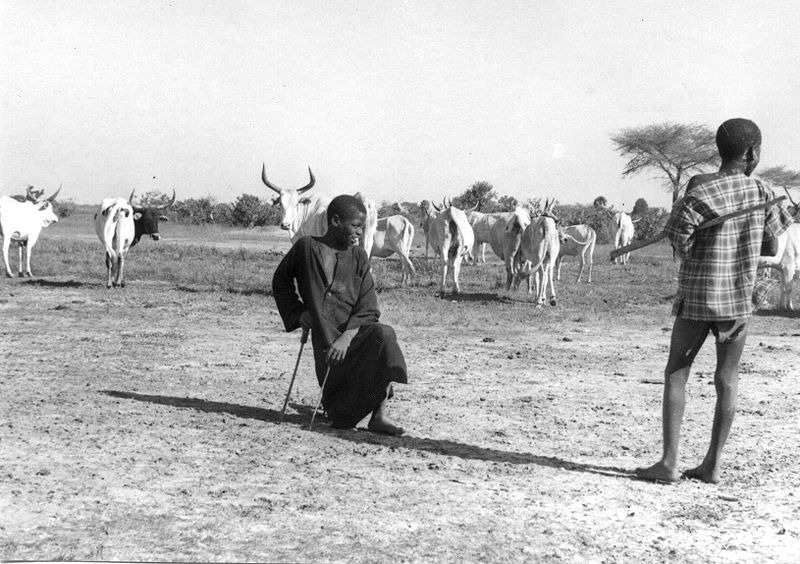

review§ § § Walking with Abel

Journeys with the Nomads

Of the African Savannah

Anna Badkhen

(Riverhead)Who is this Badkhen, and how does she stand it; a year with the cow people of Mali? As any of us who have lived in or near the desert, there is always the wind, and the eternal, pervasive, invasive grit. Here, we can hide in our trailers or our shacks. There, in the open Sahel, there is no hiding. It's hot, it's gritty, and it's merciless. The wind is called "harmattan." It drives some crazy.To be there with her is to be with the language. The salaams --- this is Muslim country --- and marabouts and the doum palm and the rimaib (the "black people") and wakula, the "gentle genies." Badkhen becomes Anna Bâ, for if she is going to live with the Fulani, she must become at one with them. And her new name, Bâ, they explain, is an ancient name, and an honorable one.

Will her joining this family cause heads to turn? "A woman came with an empty purple lunchpail stamped with yellow and white and pink hearts and the inscription I [HEART] AFRICA and paid for her butter in coins that Fanta accepted without counting and tied into the corner of her headscarf."

"Where'd you get the white woman?"

"It's my white woman."

"Eh?"

"Get outta here!"

"Sly Fulani!"

"It's true. She is staying with me."

"Where are you from, white woman?"

"Where are you from?" my hosts in an Afghan village would ask, my hosts on a farm in Iraq, in the velvet mountains of Indian Kashmir. Defenders of their ancestral homes from foreign armies, from their own abusive governments, from cataclysms and manmade devastations."

What could I tell them? I had grown up an outcast in a country that no longer existed, in a city that had since changed its name. An underweight and sickly specimen of a despised minority, a Soviet Jew. I had moved away, and I would move again, and again. My point of departure was never the same. I was transient, in transit: the Wandering Jew. Ahasuerus.

§ § § It is this elegance in writing that finally catches us, reminding us above all of Ryszard Kapuściński, of whom we once wrote, "Great journalism reads like a great novel, or an epic poem, or a well-wrought short story." And we offer the thought that Badkhen is just such a fine journalist. She convinces us in Walking with Abel that she has found compatriots to wander with. The Fulani, her new wanderlust friends, know that words like time and space and place and home and travel must change their meanings when you become a nomad.

Those of us who depend on the regularity of hearth and home and a place known as "my house" cannot exist in a completely different mode. Time cannot be time as we know it; it comes as another element. For the nomads, it may even change the concept of waiting: "How long would they have to wait? There existed no calendar for the nomads, no dates. There was barely time at all: only cycles."

The sunrise like a huge white celebration in the east, the molten fisher's float of sunset. The children dying in the night, the women circling back to sit with another in mourning. The droughts and the deluges. The slow spasmodic migration to and from seasonal grazing lands, and the shorter rhythmic patterns of ferry rides back and forth across the river and its anabranches and seasonal affluents, the roundtrip slogs to pasture, water, market. And the waiting, always the waiting: for rain, for thicker grass, for the next move.

Go to the complete

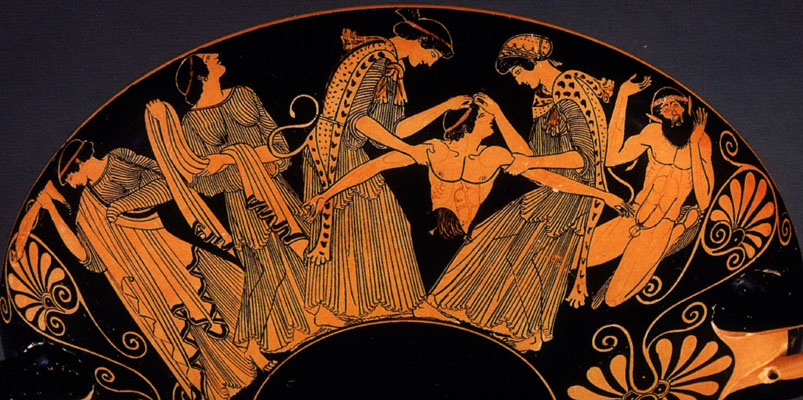

review§ § § Beauty is a Wound

Eka Kurniawan

Annie Tucker, Translator

(New Directions)Those of us who fell asleep while trying to absorb "The Oresteia" or "The Trojan Women" or "Oedipus" or "The Eumenides" can now be spared a snooze in the playhouse, for we find many of the elements of classic Greek tragedy roped together here in Beauty Is a Wound. If you have never been able to figure out the twists and turns of the curse of the house of Atreus, here's where it all plays out. Atreus kills the sons of his brother Thyestes, cooks up the two tiny babes in a savory pot-pie with thyme, fennel and bay-leaf, which he then feeds to unknowing Thyestes --- who burps heartily after his mysterious (but great) sacrificial dinner.And this starts the curse a-ticking, the whole ball of wax, taking us into the Trojan war, and Clytemnestra killing husband Agamemnon, and she in turn murdered by her son and daughter Orestes and Electra --- and soon thereafter morning (or mourning) becomes Electra and, finally, the curse dies out because the gods have gotten bored ho-hum with all these people screwing then murdering each other, eating each other burp.

With Beauty is a Wound, you can participate in an up-to-date family rape-murder-kill-eat curse, told by a master story-teller from our own time . . . instead of one of those looming up mysteriously from ages past.

They say that this book was written before Kurniawan turned forty. If so, I am wondering how this kid [see author's photo above] can cram so many tricks into one book, tricks that actually build an epic. It's beyond me, especially the best trick of them all: making us stay up half the night so that we can live through all this love and magic and hate . . . and finally participate in the realization that comes to us, to them all, after burying yet another member of the family: the boy Krisan, when Alamanda and Maya Dewi are trying to comfort Adinda, explaining,

"We're like a cursed family," Adinda sobbed.

"We are not like a cursed family, corrected Alamanda, "We are truly and completely cursed."

Beauty is like a wound.

Go to the complete

review§ § §

The Milli Vanilli Condition

Essays on Culture in the New Millennium

Eduardo Espina

Travis Sorenson, Translator

(Arte Publico)With the ten quotes from above, I am hereby testifying that I have read, "with an excess of admiration, a certain work of a certain author." For the author, in this case, Eduardo Espina, is a fascinating, funny, even I may say --- a dreamy writer. He can also be who can be excruciatingly astute. He often, as he does here, goes off on tangents that are not so fascinating, not so funny, or, if I may say so, not all that dreamy.

- The coming of cell phones makes us all "a universal witness, a thief of instants with visual posterity included."

- Since Japan is surrounded by water. It is mysterious. "Water wants to get in so that it can get to know it." Thus tsunamis.

- During one tsunami, homes --- made of wood --- were "floating by, on their way to forgetfulness, as if asking where their home was."

- Espina lived in Texas. On September 11, 2001, "People spent the day watching television, since there is where reality goes first."

- On September 12, "the destruction of the World Trade Center could be seen commercial-free at all hours and on all channels." Everything was then covered in flags. "Just as with mushrooms after the rain, they were everywhere. The era of the flag had arrived. Houses and other buildings had grown flags during the night, even though no one had watered them."

- Serial killers may also be "necrophiliacs." Jeffrey Dahmer, according to his lawyer "was a necrophiliac who loved to have sexual relations with non-loving objects." Espina avers that he might be the "Most popular serial killer in the history of pop culture."

- He also claims that Dahmer could be seen as a "cereal killer" because, like other of his cohort, he was "capable of eating their prey during dinner or breakfast (in this regard Dahmer was very democratic, since he would eat his victims at any hour of the day.)"

- Espina is a poet, and he gives live readings. When a fan came up at the end of his presentation, saying that "listening to me has made him want to write, I feel compelled to invite him to plagiarize me," because then Espina is "the writer who has spawned the impersonation of a fellow human being." He points out that, according to Paul Gauguin, "Art is either plagiarized or revolutionary."

- This leads him to reveal to us that translators can improve the original. "The famous Hungarian art forger Elmyr de Hory looks at the camera and states with convincing naturalness that on his good days he painted Matisses that were, without a doubt, better than those painted by Matisse himself on his bad days."

- Plagiarism might be defined --- as it is here --- as "an altruistic tribute according to which human beings testify that they have read, with an excess of admiration, a certain work of a certain author."

But whatever his failings, the good stuff is so beyond just good that I may now claim publicly that I have for him an excess of admiration.

Go to the complete

review