Symphony for the City of the Dead

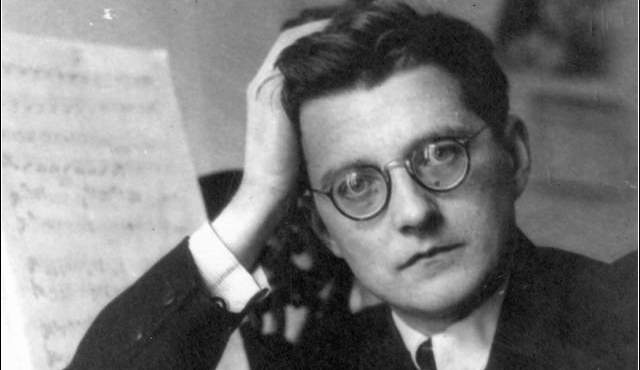

Dmitri Shostakovich and the Siege of Leningrad

M. T. Anderson

(Candlewick Press)

The Symphony for the City of the Dead tells us about Shostakovich's Seventh Symphony, now known as the "Leningrad Symphony." It was supposed to be a paean to those who survived the 872 days of the Siege of Leningrad --- from September 1941 until January 1944 --- where 1,500,000 soldiers and civilians died, and another 1,500,000 were evacuated. The thrust of this book is its creation, with a bit of Shostakovich's life up to the time of the composition, the siege itself, and the life of the composer afterwards.One is invited to decide if the composition was solely about bravery of those who lived and died in defense of the city . . . or whether the Seventh Symphony was, sub rosa, a composition exposing the viciousness of Stalin's rule both before and after Leningrad.

It is probably impossible for us to know which, because, by the time of its composition, Shostakovich learned from previous flailings by the Soviet cultural police that it was best never to reveal what a piece of his "meant." As Anderson writes,

Shostakovich himself does not seem to have restricted the meaning of the piece --- hearing in it instead an abstract depiction of "the bondage of the spirit," all those petty ugly things that grow disastrously within us and lead us all in a dance of destruction.

The Symphony for the City of the Dead has many fascinating elements that deserve our attention, especially two that piqued my curiosity from the beginning. Number one: what was the siege like for the composer himself, for his family, and for those who managed to live through it? Secondly, how did this composer who --- in his youth --- wrote some fairly outré pieces --- manage to survive long enough, during the many orgies of state-sponsored terror . . . to eventually write this "noble" symphony that was accepted by all, even by the Soviet brainwashers who ran the cultural show.

Photographs of Dmitri Shostakovich taken in the later years of his life show a man haunted. They say he could barely sit still, would stand up, sit down, pace nervously, then sit down uneasily again. And with good reason. He was the major Russian composer during the long and ugly reign of Stalin, during a time when many of his fellow artists were being shot or sent off to Siberia for suspected disloyalty . . . for composing works that did not fit the ditakts of the ruling elite.

For instance, Osip Mandelstam's "Kremlin Highlander" --- a poem comparing Stalin to a high-living cockroach "in gleaming boots" --- managed to get the poet shipped off to Cherdyn' in Siberia, and ultimately to his death.*** The threat of death as compensation for a work of art would, we imagine, give one a few jabs in the gut at the moment of composition. As friends of Mandelstam noted, only in the Soviet Union could one be put to death for a work of art.

It would be especially nerve-racking for Shostakovich. In 1936, Stalin attended a performance of his opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District and --- midway through the performance --- stood up and left.

Supposedly, as Stalin was making his way out of the theatre, a reporter asked him what he thought of Shostakovich's music. "Etu sumbur," he growled, "a ne musyka." --- "That's a mess, not music."

Shostakovich was subsequently mocked by the official party newspaper Pravda. An unsigned review said that music, as all the arts, should be for the good of all the people, but in Lady Macbeth "The power of good music to infect the masses has been sacrificed to a petty-bourgeois, 'formalist' attempt to create originality through cheap clowning. It is a game of clever ingenuity that may end very badly." It was "muddle instead of music."

And all this is coarse, primitive and vulgar. The music quacks, grunts, and growls, and suffocates itself in order to express the love scenes as naturalistically as possible. And "love" is smeared all over the opera in the most vulgar manner. The merchant's double bed occupies the the central position on the stage. On this bed all "problems" are solved. In the same coarse, naturalistic style is shown the death from poisoning and the flogging --- both practically on stage.

Like most in the Soviet Union in the 1930s, Shostakovich knew that he could be sent off to the gulag for crossing some unknown or unexpressed boundary. It was a time when party members were purged. "Futurist painters were purged. Leningrad factory bosses were purged. Train operators were purged --- so many that one railway line had no one left working on it. When the NKVD had finished purging other groups, then Stalin purged the NKVD itself. He decided they were getting too powerful."Historians were purged. Diplomats were purged. Collective farmers were purged because during the harvest, the crops were crawling with ticks. The regime claimed that the ticks had been spread by antirevolutionary masterminds.

The mid-thirties were to become known as the time of "The Great Terror." In 1937, Marshal Tukhachevsky, a Red Army strategist, was tried for "being an agent in pay of the German military, the Reichswehr." He was a friend of Shostakovich, and the composer was called in by an agent of the NKVD and asked if he knew the general. He admitted that he did. He was then asked about when they met together, what did they talk about.

"About music."

"And politics?"

The conversation was getting dangerous. Shostakovich could tell. He answered, "No, there was never any talk of politics in my presence."

"The investigator sat back. He said that it was Saturday and that he would give Shastokovich the weekend to remember. "You must recall every detail of the discussion regarding the plot against Stalin of which you were a witness."

Over the next forty-eight hours, the composer "destroyed any papers that might possibly be incriminating. He spent the weekend saying good-bye to Nina and his baby daughter." On Monday he returned to the offices of the NKVD, was told to wait in the front office by a security guard. "He waited for hours. Finally, he timidly spoke to a security guard. The guard thumbed though the list of appointments and couldn't find Shostakovich's name. 'What is your business? Whom have you come to see?' Shostakovich explained he was there to see an investigator called Zakovsky. He had an appointment.

"Ah! Now the guard understood what was going on. He apologetically told Shostakovich that over the weekend Zakovsky had been condemned and arrested. His appointments had apparently been cancelled. They were not going to be rescheduled."

Shostakovich left the building. For the moment, he was free. As in some absurdist fable, his executioner was in line for execution. He wandered home across the Neva River, befogged and bewildered by his tenuous reprieve.

When the NKVD is carting everyone off in the night, and after this near-disaster, to the surprise of the friends of Shostakovich he dared to continue to compose, completing his Fifth Symphony in November of 1937. One of his friends, Lyubov Shaporina, said that everyone was worried about his future. "I wake up in the morning [she wrote] and automatically think: thank God I wasn't arrested last night. They don't arrest anyone during the day, but what will happen tonight, no one knows. . . . Every single person has enough against him to justify arrest and exile to parts unknown."

The symphony was presented in concert on 21 November 1937, conducted by Evgeny Mravinsky. One biographer wrote, "Shostakovich's fate was at stake." One of Shostakovich's friends later reported that "By the third movement, a slow lament, Shostakovich's friend Isaak Gilman looked around the hall and saw that the faces of the men and women around him were wet with tears. This was a song for all their dead." At the end of the performance, when no one knew what was to become of the composer, Anderson tells us,

Shostokovich was still stiffly bowing in front of the delighted mob. Two of his friends realized it might be a disaster if he were caught standing there when there was any trouble --- a spontaneous protest, a riot, anything that might attract attention to him.

They whisked him away.

It appeared that, so long as the regime didn't intervene and arrest him, his symphony was a tremendous success.

The composer himself was to say later,Even before the war in Leningrad there probably wasn't a single family who hadn't lost someone, a father, a brother, or if not a relative, then a close friend. Everyone had someone to cry over, but you had to cry silently, under your blanket, so that no one would see. Everyone feared everyone else, and the sorrow oppressed and suffocated us.

As Anderson writes, "This requiem allowed them to mourn together in public. In this threnody, there are fragile solos, weak shoots or tendrils of a theme that might easily get crushed underfoot. The full string orchestra takes up those thin melodies and tries them, too, as if, after a great shock, they all are teaching themselves to feel again. They are learning to sing of their own sorrow."

The symphony was wildly applauded that night, and wherever after it was performed. To quiet possible critics within the regime, Shostakovich published several articles to explain the piece. Anderson writes that the article implied "that the symphony was perhaps about his own turmoil after being criticized by Pravda.

It was about the spiritual victory when government criticism led him to repent of his doubts, his formalism, and his neurosis in favor of a new faith, a new hope. He wrote that of all the reviews, one that particularly gratified him said that "the Fifth Symphony is a Soviet artist's practical creative answer to just criticism."

In other words, the composer successfully dodged the bullet. "The phrase 'a Soviet artist's practical creative answer to just criticism' was repeated again and again when the symphony made its way across the oceans to America." Was he, as some thought, "putting on a smiling mask to avoid government censorship?"

Certainly, some of his friends believed this. "He described his music to the Party as joyous and optimistic, and the entire pack dashed off, satisfied," said soprano Galina Vishnevskaya. "Yes, he had found a way to live and create in that country . . . But he learned to put on a mask he would wear for the rest of his life."

And as we listen to it now you may agree with some who found that the "finale was optimistic . . . " Yet one writer in Moscow reported that "the ending does not sound like a resolution (still less like a triumph or victory), but rather like a punishment or vengeance on someone. A terrible emotional force, but a tragic force."

And one of the members of the official Moscow Composer's Union --- in February of the next year --- found himself to be "confused." He didn't find the ending celebratory. "The general impression of this symphony's finale is not so much bright and optimistic as it is severe and threatening."

It was a writer friend who quickly figured out how Shostakovich was playing it.

The poet Pasternak, who had cautioned his friend Mandelstam for speaking too openly, even in a whisper on the middle of a bridge, clearly felt that the Fifth Symphony was about Stalin's purges and the Great Terror. "Just think," he groused jealously, Shostakovich "went and said everything, and no one did anything to him for it.

The artist gamed it perfectly: compose one thing, say another. Who's to know? Shostakovich writes that he has changed, that he now understands his artistic duty is to compose only music which, as in all the arts, should be for the good of all the people. In other words, compose whatever he thinks he can get away with, then immediately write articles to say that the music is a testament to his willingness to purge his earlier mistakes; that he has learned from these mistakes, and the newer works will simply prove his desire to work for the betterment of society. Who is to say otherwise? The composer has spoken; who can doubt him?

No matter how he did it, some believe that Shostakovich was ultimately a hero. In all these years, he slept with a suitcase at the ready filled with essentials he felt he would need on a trip to the gulag. At times, he even slept just outside the apartment door, on the landing, so that his arrest would not disturb his wife and his child. He had, perhaps, the power granted to one who knew himself to be doomed . . . and so he continued to do what he did best: confuse those who held the whip, so that when they finally came to murder him, he would not give them the comfort of taking him by surprise.

There is something in the Fifth Symphony that spoke to many of us afterwards. Even now, when I find a good version of it on the internet, I can be captured by it as I was in 1948. Although I lived in a family that took classical music seriously, I can't remember my being interested in any of the records we owned --- the usual Brahms, Beethoven, Tchaikovsky, Schubert symphonies. But when I came across Shostakovich's Fifth in its album of 78's (I think it was the version conducted by Evgeny Mravinsky and the Leningrad Philharmonic), I put it on to play and play and play again over a period of a year as I read.I was at the time entranced by H. G. Wells' Seven Famous Novels, and I often read the tales as I listened to the Fifth. They seemed to belong together: Shostakovich in the background during my travels in the time machine, hiding in the ditches with me during the invasion from Mars, living through the plight of the invisible man (who wanted to be invisible no longer). My sister later told me she thought --- no, she knew --- that I had gone bananas.

Mind you, my favorite music at the time was Nat King Cole, Tommy Dorsey, Doris Day and the blues --- Lightnin' Hopkins, Li'l Son Jackson, Leadbelly. If I could go back and ask myself why I, at age 15, was so entranced by these works from outer space . . . if I only had that power. But, can only look back and guess at the shadow of passion that we carried about with us then. The me that thought it was me back then suspects that it is no longer around so I won't be able to question the me who I thought I was back then in 1948 when I thought I understood it all.

--- L. W. Milam***Stalin's EpigramWe live, not sensing our own country beneath us,

Ten steps away they dissolve, our speeches,

But where enough meet for half-conversation,

The Kremlin hillbilly is our preoccupation.

They're like slimy worms, his fat fingers,

His words, as solid as weights of measure.

In his cockroach moustaches there's a hint

Of laughter, while below his top boots gleam.

Round him a mob of thin-necked henchmen,

He pursues the enslavement of the half-men.

One whimpers, another warbles,

A third miaows, but he alone prods and probes.

He forges decree after decree, like horseshoes ---

In groins, foreheads, in eyes, and eyebrows.

Wherever an execution's happening though ---

there's raspberry, and the Ossetian's giant torso.--- Translation by Scott Horton