Symphony for the City of the Dead

Dmitri Shostakovich and the Siege of Leningrad

Matthew Tobin Anderson

(Candlewick Press)

The temperatures that winter were often down to twenty below zero, and so the corpses did not decompose. Bodies were usually stacked in apartment courtyards or cellars.Beyond fatigue, there was another good reason to delay taking the dead out of an apartment: until the death was declared, the family could still collect rations in the name of the deceased.

One woman, Klavdia Dubrovina, described sleeping in an apartment with her friend and with a dead family who were stacked, frozen, around the room. The windows had all been blown out, "and the frost, the cold, were frightful." One day Dubrovina came home and discovered her friend had died, too, during the day. "Yes. I came home and she was lying there dead. Somehow this was also a matter of indifference to me. People were dying all around. I'd simply get into that burrow [in the bed] --- I'd take my coat and boots off --- and I'd get into it, for the cold was frightful. and I'd put on an old scarf, too. When I rose in the morning that scarf was frozen to my skin all around my neck. I'd tear it off, get up, put on my coat and go to work."

Death had lost its dignity. As one man, Dmitri Likhachev, was dragging his father's corpse to the cemetery, he was passed by a procession of gravediggers' trucks.

I recall one truck that was loaded with bodies frozen into fantastic positions. They had been petrified, it seemed, in mid-speech. mid-shout, mid-grimace, mid-leap. Hands were raised, eyes open. I remember the body of a woman: naked, brown, thin, upright. . . . The truck was going at speed, leaving her hair streaming in the wind . . . as they went over the potholes in the road. It looked as if she was making a speech --- calling out to them, waving her arms --- a ghastly, defiled corpse with open, glassy eyes.

A woman who found employment loading those trucks described how she stopped feeling anything at the sight of the dead. "[At first] I was afraid of dead bodies, but I had to load those corpses. We used to sit right there on the trucks with the corpses. and off we'd go. And your heart would seem to switch off. Because we knew that today we were taking them, and tomorrow it would be our turn, perhaps." Many people similarly described this emotional emptiness, the heart "switching off."

At the entrance to one cemetery, some comic gravedigger had propped up a frozen corpse with a cigarette in its mouth, pointing the way to the burial pits. Citizens, wrapped head to foot in their winter coats and hats, dragged their mummy --- wrapped loved ones past through the brown snow. The ground was frozen, so mass graves had to be excavated with explosives.

Gradually, like the immigration of an insidious, phantom population, Leningrad belonged more to the dead than to the living. The dead watched over streets and sat in snow-swamped buses. Whole apartment buildings were tenanted by them, where in broken rooms, dead families sat waiting at tables. Their dominion spread room by room, like lights going out in evening.

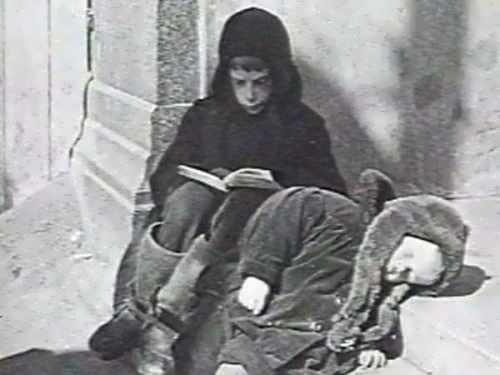

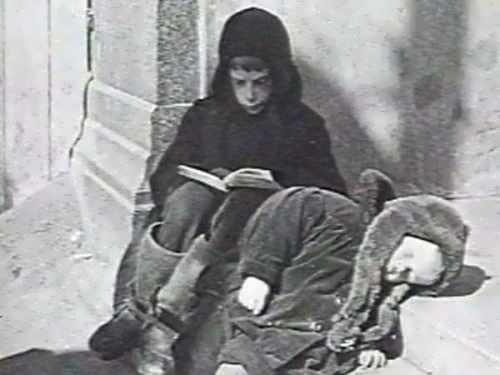

The elderly and the very young tended to succumb to starvation first. Statistically, gender also played a role: "Within a single family . . . the order in which its members typically died was grandfather and infants first, grandmother and father (if not at the front) second, mother and older children last."

In the case of the family Shostakovich left behind --- his mother, Sofia Shostakovich; his sister Maria Frederiks; and his nephew, Dmitri Frederiks --- there were no men left. Maria's husband, the physicist Vsevolod Frederiks, had been off in a prison camp for years. (He would die of starvation there in 1944.) Sofia, apparently, was hardest hit by hunger. She was skeletal.

Shostakovich sent her money. It was often delayed, or disappeared entirely. (Letters were regularly opened and searched by the NKVD.) In any case, paper money was almost valueless in Leningrad by this point. People bartered. They exchanged a gilt clock from some tsarist salon for a few meat patties; an inlaid wood dresser, in the family for generations, for a little cooking oil.

§ § § Among the living population, families and coworkers watched one another gradually manifest the symptoms of dystrophy, the malfunctioning of the body as it succumbs to hunger. "Hunger changes the appearance of all," wrote the diarist Elena Skrjabina. "Everyone now is blue-black, bloodless, swollen." Leningraders came to call this discoloration of the skin a "hunger tan." As the weeks went by, "People were discovering bone after bone" jutting just under the skin, another diarist wrote. The gums of the starving receded. It looked as if their teeth grew with hunger, as if the need to devour dominated their faces, kind or cruel. Eventually, their teeth began to fall out.

Their movements became slow and mechanical. Their speech slurred as their vocal cords atrophied. It became difficult to move at all. A survivor recalled, "It was roughly the feeling that your foot wouldn't leave the ground. Can you understand? The feeling that when you had to put your foot on a step, it just refused to obey. It was like it is in dreams sometimes. It seems you're just about to run, but your legs won't work. Or you want to shout out, and you've no voice."

Even though factory employees received more substantial rations than any other group except soldiers, work was grinding to a stop as people on the assembly lines slowed. They moved like broken automatons. At the Izhora Factory, a diarist wrote, "Everybody is now walking very slowly, and some can barely lift their legs. It is hard to imagine such debilitation. We are just sitting here starving."

The Soviet utopians of the 1920s had fantasized about a mechanized future where people were part of a vast machine. The Cubo-Futurists had painted visions of human cogs and gears, and composers had written clangorous works depicting the vitality of industry.

Now humans were winding down beside their machines. Empty streets echoed with the slow ticking of the metronome through iced loudspeakers. The city, like a giant clockwork mechanism unwound, froze slowly to a stop.

Perhaps the most heartbreaking collapse in this mass starvation was not physical, however, but moral. People were forced to confront nightmare decisions about who they should allow to live or die. As the soldier who returned from the front to find his daughter dead wrote, "There is much that is revolting. But that's life: a mother of four children takes the baby from her breast in order not to die herself. The baby will die. But then three others will live, who otherwise, without their mother, would die. Was the mother's decision justified? No doubt about it, it was. When Maria [his daughter] bought a stolen bread ration card, she did right, yes, she saved the lives of three children."

These ghastly decisions were made in a welter of starvation, which sharpened the senses but confused thought. "The brain is devoured by the stomach," said one sufferer. Tempers flared irrationally. Children subsided into dementia, sitting at the table and tearing up paper into smaller and smaller pieces or wailing without cease. Deterioration caused some people to go insane. Brothers killed brothers for ration coupons. Parents murdered their own children.

As a foreman at the Kirov Tank Works said, "Human beings showed what they were like in those days. I don't suppose people had ever before witnessed such a revelation of greatness of soul on the one hand and of moral degradation on the other."

There were those who banded together to find strength and connection. Then there were those who looked out only for themselves and who hunted alone.

§ § § There are two words for cannibalism in Russian: trupoyedsrvo ("corpse-eating") and lyudoyedsrvo ("person-eating").

Corpse-eating was far more common. Mourners would descend to their apartment buildings shed or well house, where their relatives' bodies were being stored, only to discover that the thighs or buttocks had been hacked off in the night. Militia searching buildings for survivors came across the bodies of the neglected dead with limbs missing. One man found several heads in a snowdrift; a little girl's still had its blond hair in long Russian braids. The NKVD files are unspeakably macabre. One family (a father, a mother, and a thirteen-year-old boy) were arrested for stealing bodies from a hospital morgue, presumably for resale as food. A nurse was arrested for purloining amputated limbs from the surgery room floor. A mother shared the body of her eleven-year-old son with two fellow workers from the Lenin Plant.

The criminal profile of corpse-eaters was surprising. Only 2 percent had a previous criminal record. They were primarily women, uneducated females with no employment and no local Leningrad address. They were, in other words, often refugees who had fled to the city and who therefore did not have ration books at all. They had to make a choice between eating those already dead or dying themselves.

A Leningrad woman named Elena Taranukhina, who lived with her mother and her baby daughter, was disgusted to find that several of the corpses in the courtyard of her apartment complex had been hacked up for food. This was not the worst of it, however. One morning as she stood in one of the endless bread lines, waiting for rations, she "felt that something was horribly wrong," and left her place in the queue to rush home.

When she got there, the scene was like one out of the worst Grimm's fairy tale: The baby was in the aluminum bathtub over a flame, but without water. The grandmother, pushed over the edge into insanity by hunger and cold, was cooking her granddaughter, muttering, "What a fatty child, what a fatty child, what a fatty child."

Taranukhina restrained the frantic old woman and saved her daughter. Two days later, the grandmother died of hunger.

This was the line between "corpse-eating" and "person-eating": killing someone for food.

Most of those who were caught and tried for person-eating acted alone. It was, after all, the ultimate expression of individualism: the absolute belief that one's own life matters more than another's. One woman, a girl at the time, described being chased down a dark corridor by a cannibal who no longer looked human to her. As he scrambled after her through the dark, he "looked like a beast." He had an ax. She was saved by some passing soldiers.

A woman named Vera Lyudyno recorded the disappearance, one by one, of children in her apartment building. Finally their clothing was found in the apartment of a nearby violinist, along with the clothing of his own five-year-old son.

In another part of the city, a mother whose child disappeared went to the police. They directed her into a room filled with crates of clothing marked by number. They told her to search for her child's clothes. When she found the clothing, she could report the number on the crate to the police and they would tell her the district where her child was eaten.

Rumors whispered at the time that there were organized bands of cannibals hunting in the streets and alleys. A young couple, for example, went to the Haymarket to search for a pair of felt boots. As currency, they clutched 600 grams of bread they had carefully hoarded for weeks. The Haymarket was located in the crooked quarter of the city described by the great Dostoyevsky in his novel Crime and Punishment and was a place fraught with pickpockets and con men in the best of times. The couple searched the stalls and could only find stiff, old, ill-fitting military shoes --- until they spied a tall man in a nice sheepskin coat, serenely holding a single boot and searching the crowd for buyers.

They approached him and asked about the boot; he said that yes, he had two, but he had left the other one back at his apartment for safekeeping. He would give them the pair for two pounds of bread. The young couple haggled with him. Finally, they got his price down to 600 grams and showed him their loaf. He agreed to take the young man back to his apartment to fetch the other boot.

The young man followed the gentleman in sheepskin through the maze of streets to an apartment building. Walking up the stairs, he felt a strange chill. He couldn't help but notice how well-fed the man looked. They walked up floor after floor. The man seemed to have a spring in his step.

When they got to the top of the staircase, the man in the sheepskin coat said, "Wait for me here." He knocked on a door.

"Who is it?" said a male voice from inside.

"Its me," said the man in the sheepskin coat. "With a live one."

The door opened a crack, and the young man spied a hairy red hand, and, in the background, lit by bobbing candlelight, "a glimpse of several great hunks of white meat, swinging from hooks on the ceiling. From one hunk he saw dangling a human hand with long fingers and blue veins."

He bolted toward the stairs as the two cannibals made a rush for him. Though he was weaker than the two sleek, well-fed person-eaters, fear and alarm gave him speed. He tumbled out into the street. Farther up the lane, a truck of soldiers was headed out of the city for duty on Lake Ladoga. The young man shouted, "Cannibals!" and the truck pulled to a halt; the soldiers came running.

He saw them dive into the building. A few seconds later, shots rang out.

When the soldiers came out of the building, they were carrying the cannibals coat, complaining about the bullet hole that had ruined it. They told the young man that they'd found the remains of five bodies in the apartment, and handed him a hunk of bread --- his, as it turned out --- that they'd reclaimed from the murderers. With that, they climbed back in their truck and headed off to the east.

Horror stories like this --- and the issue of Leningrad cannibalism as a whole --- could not be talked about openly during the Soviet period. Such an admission of the breakdown of society was considered demoralizing. Only in 2002 were NKVD files opened so academics could discover the gruesome statistical realities of person-eating.

It appears that especially in late January and in February, when order utterly broke down in some districts of the city, there really were a few organised cannibal bands that hunted down lonely military couriers for food or lured people from bread lines and clubbed them over the head. By and large, the far greater danger was those lone individuals who lost contact with others and were driven crazy by animal hunger.

There were nine arrests for cannibalism in the first ten days of December 1941. Two months later, this number had jumped to 311. A year later, the final figure, which includes arrests for both corpse-eating and person-eating, was 2,015. Those who ate the dead usually got off reasonably lightly; those who murdered and then ate their victims were shot.

What does this mean about us as an animal? Was this creature that loped down sooty corridors, hunting others, what we all are at heart?

There were many who came to think so. An anonymous eyewitness who was eleven years old in 1941 later wrote:

After the blockade I visualized the world in the shape of a beast of prey lying in wait. . . . I grew to be suspicious, hard, and as unjust to people as they had become to me. As I looked at them I would be thinking, "Oh yes, you're pretending at the moment to be kind and honest. Yet, take away your bread and warmth and light and you'll all turn into two-legged wild beasts." And it was during the first few years after the blockade that I did a few abominable things which to this day lie heavily on my conscience. It took almost a decade for me to become rehabilitated. Up till about the age of twenty I felt that something inside me had grown irreversibly old and I looked upon the world with the gaze of a broken and all-too-experienced person. It was only in my student years that youth came into its own and the fervent desire to become involved in work beneficial to mankind enabled me to shake off my morbid depression

--- From Symphony for the City of the Dead

Dmitri Shostakovich and the Siege of Leningrad

M. T. Anderson

©2015, Candlewick Press