Walking with Abel

Journeys with the Nomads

Of the African Savannah

Anna Badkhen

(Riverhead)

I've gone on some dotty trips in my day. Like trying to visit Algeria in the middle of the eight-year Algerian War of Independence (the Moroccan border police wouldn't let me through); or going to Madras for a thirty-day South Indian music concert (I was very fond of Indian classical music, but after a month of it, I longed for an afternoon with the Beatles); or spending ten days with a drunken love in San José, Costa Rica (you can always tell when he had arrived home: stale sweat and old rum smell when we open the door.)Not only have I attempted travel in bizarre places, I have doted on odd travel books. Like one we reviewed several years ago, The Lonely Planet Guide to Afghanistan. Who in their right mind would take the grand tour of Afghanistan then (or now)? Well, Paul Clammer would, that's who. He writes that "the best time to visit Afghanistan is late summer, and he speaks of the fruits of the market, sweet grapes from Shomali and "fat Kandahari pomegranates and melons everywhere."

We have to love this one because of the editor's affection for a loony country ... made even more loony by armed interventions from abroad,

we concluded.

Then there's a travel book on Molvanîa. Who? We browsed it and found some odd passages, like

The pig is generally considered the symbol of Molvanîa. Believed to be sacred by many, these animals may only be slaughtered Monday to Saturday. Pigs are widely used throughout the country for meat, milk and --- in remote areas --- companionship.

Spurious? Well, yes --- but in such a jolly way, who can resist.

Or the oddest of international tests, where André Tolmé golfs his way across Mongolia. Which forced us to report

This is not just the tale of a guy living with the consequences of his decision to do something dotty. It is also an excellent guide book to any of us who may be thinking of visiting Mongolia (with or without golf club). It is also extremely funny, one of the best belly-laughs I've run into in some time.

§ § § Now, let's take up the case of Anna Badkhen. She's fully in the traditions of Freya Stark, of whom we wrote, "She had became mesmerized with what we then called 'The Orient.'

Starting in 1927, she traveled through the Middle East, often alone, often depending on the good will and kindness of strangers. Baghdad Sketches takes us into Iraq, with side trips to Najd, Yezidi, 'Ain Sifneh, Samarra, Tekrit, and finally Kuwait ... a country she adored.

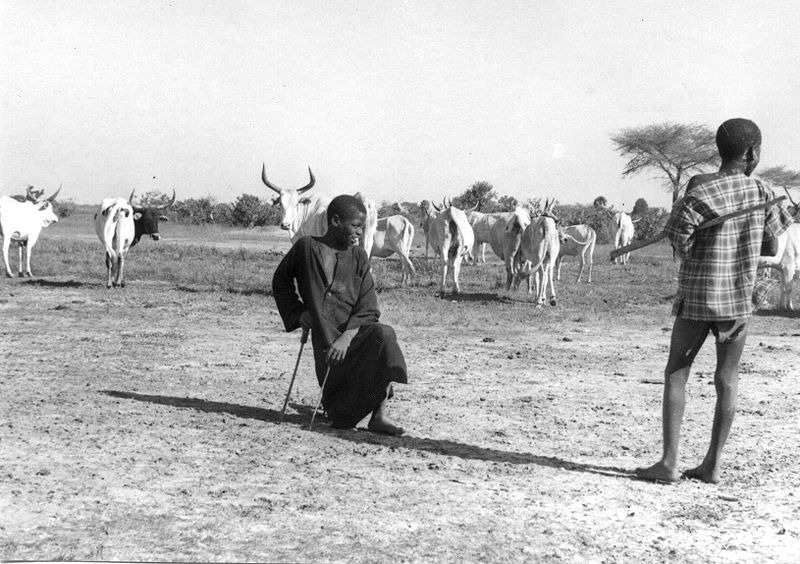

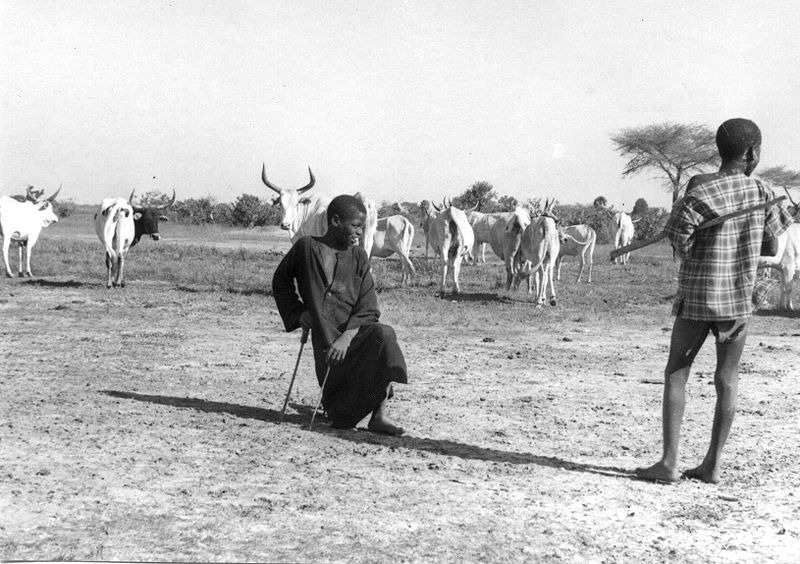

Badkhen, too, in Walking with Abel, isn't going about with the nomads to give us an international reality show. She is interested in what the nomads do, how they live. What is it to place one foot before the other for days and weeks and months, following a herd of cows and cowboys (and their wives, and children, and cousins), going, in this case, from the drought-stricken plains of central Mali up the steppes of Hayré, to be with the twenty million Fulani who meander back and forth through Central Africa?

And Badkhen isn't just jetting in there to take pictures for National Geographic. She wants to live with them. She goes to the elders there in the bourgou by the Bani River to seek permission to join a family, to be with them, and walk with them, and eat with them; to sleep in their huts, to learn their language.

When they break camp, "As the Fulani had been doing for thousands of years, the family notched and notched the routes of the ancient transhumance deeper into the continent's bone, driven by a neverending quest for pasturage, a near worship of cattle, and the belief that God created the Earth, all of it, for the cows."

Like Stark, Badkhen is a rare travel writer. She can do something so few of them can. She can immerse herself in the lives of the Fulani, then transform their dusty, poor, thankless nomadic lives into near poetry.

For instance, if you are a wandering cowherder, you must learn the stars, for "it was simply impossible for the Fulani cowboys not to know them --- maybe not all, but some. They had to."

Without such knowledge, Oumaroou explained, they wouldn't know to avert their eyes on the night the Pleiades first sprayed into the eastern sky. Only three creatures could look at the Pleiades on the first night of the constellation's heliacal rising without harming themselves, a black horse, a strong cow, and a black addax. But if a man saw the constellation on that night, he would die.

Badkhen (and the reader) sleep on the earth aside the women and the babies, eat the millet and rice (always mixed with milk), shea butter (smelling of chocolate and shit), trudge into town for the Monday market (calabasas on their heads), drink the brackish water, and live by the rhythm of the cows.

Who is this Badkhen, and how does she stand it; a year with the cow people of Mali? As any of us who have lived in or near the desert, there is always the wind, and the eternal, pervasive, invasive grit. Here, we can hide in our trailers or our shacks. There, in the open Sahel, there is no hiding. It's hot, it's gritty, and it's merciless. The wind is called "harmattan." It drives some crazy.

To be there with her is to be with the language. The salaams --- this is Muslim country --- and marabouts and the doum palm and the rimaib (the "black people") and wakula, the "gentle genies." Badkhen becomes Anna Bâ, for if she is going to live with the Fulani, she must become at one with them. And her new name, Bâ, they explain, is an ancient name, and an honorable one.

Will her joining this family cause heads to turn? "A woman came with an empty purple lunchpaid stamped with yellow and white and pink hearts and the inscription I [HEART] AFRICA and paid for her butter in coins that Fanta accepted without counting and tied into the corner of her headscarf."

"Where'd you get the white woman?"

"It's my white woman."

"Eh?"

"Get outta here!"

"Sly Fulani!"

"It's true. She is staying with me."

"Where are you from, white woman?"

"Where are you from?" my hosts in an Afghan village would ask, my hosts on a farm in Iraq, in the velvet mountains of Indian Kashmir. Defenders of their ancestral homes from foreign armies, from their own abusive governments, from cataclysms and manmade devastations."

What could I tell them? I had grown up an outcast in a country that no longer existed, in a city that had since changed its name. An underweight and sickly specimen of a despised minority, a Soviet Jew. I had moved away, and I would move again, and again. My point of departure was never the same. I was transient, in transit: the Wandering Jew. Ahasuerus.

§ § § It is this elegance in writing that finally catches us, reminding us above all of Ryszard Kapuściński, of whom we wrote, "Great journalism reads like a great novel, or an epic poem, or a well-wrought short story." And we offer the thought that Badkhen is just such a fine journalist. She convinces us in Walking with Abel that she has found compatriots to wander with. The Fulani, her new wanderlust friends, know that words like time and space and place and home and travel must change their meanings when you become a nomad.

Those of us who depend on the regularity of hearth and home and a place known as "my house" cannot exist in a completely different mode. Time cannot be time as we know it; it comes as another element. For the nomads, it may even change the concept of waiting: "How long would they have to wait? There existed no calendar for the nomads, no dates. There was barely time at all: only cycles."

The sunrise like a huge white celebration in the east, the molten fisher's float of sunset. The children dying in the night, the women circling back to sit with another in mourning. The droughts and the deluges. The slow spasmodic migration to and from seasonal grazing lands, and the shorter rhythmic patterns of ferry rides back and forth across the river and its anabranches and seasonal affluents, the roundtrip slogs to pasture, water, market. And the waiting, always the waiting: for rain, for thicker grass, for the next move.