The Vienna Melody

Ernst Lothar

Elizabeth Reynolds Hapgood, Translator

(Europa Editions)

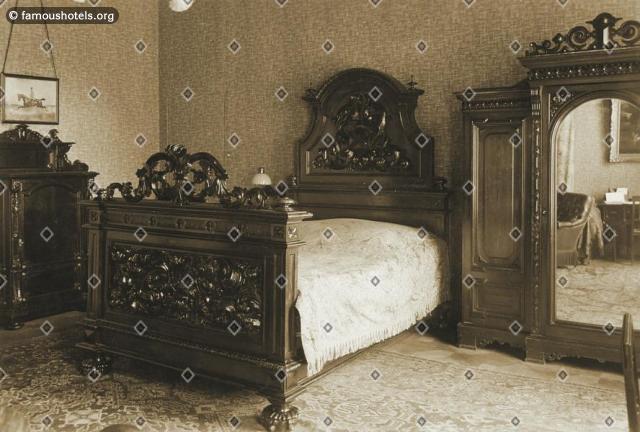

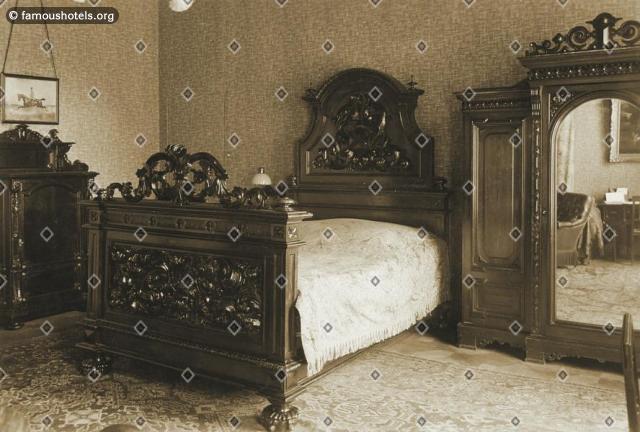

And here I am going to tell you that I spent the last four days transfixed by a fat novel, a Bildungsroman (more or less), treating of an Austrian family who build pianos for a living. Four days! I pick it up with my morning tea, leave it off for lunch, take it (and all of Vienna) with me for the mid-afternoon nap, shut it down at the time of my evening cocktail, and --- restraining myself --- spend the next twelve hours not reading it.And why this sudden enthusiasm? You know, don't you? These novels that wickedly, steathily catch you up . . . won't leave you be. Lothar knows how to build a story, brick by brick. We can but marvel at his construction, but also at the pacing that pulls us in, won't give us peace. We begin in Vienna, 1888, and end in Vienna, in 1938 --- all in the same building, there in the house at Number Ten Seilerstätte, at the corner of Annagasse. The original owner, the founder of the piano shop, dictated that his children and his children's children are all to stay in the same building, that none are allowed (ever) to leave. They're stuck with each other, and it shows: backbiting, starchy coldness, occasional blackmail, a tantrum, or murder, or chronic depression . . . and always carping carping carping. Let me out!

The only surviving daughter of the piano factory master, Miss Sophie Alt, is a good Catholic, a lady we would then have called, in the old days, "an old maid." She presides over the three floors (plus basement), with nephew Otto Alt, the proper lawyer, and young Franz Alt, upcoming director of piano factory, along with the daffy painter Drauffer, and a few not-so-memorable others of the extended, perhaps overextended, family. And we stay with them in this drafty old building for the next fifty years.

All begins with love, of a sort, Franz admitting to Aunt Sophie that he has courted a lady, and is going to marry her, and her name is Henriette, the only child of "Professor Stein of the University . . . The daughter of one of our greatest jurists." And Sophie responds, "Professor Stein is Jewish, isn't he?"

And there the issue is joined, and on that tense note, we begin our journey, mostly concerned with lovely Henriette, who will soon enough give birth to Hans, her beloved son, and he and Henriette will be the center of The Vienna Melody, so it may not be solely a Bildungsroman . . . perhaps better a Verzweiflungroman.

We will stay with the Alt family, at first hesitatingly (don't we all hesitate before we jump into a 600-page novel?), waiting until we go into despair ourselves, or, better, until we are hooked, and are able, in this case, to follow the Alts through their life in Vienna, with occasional asides into what we can think of as "real" history, where Henriette will not only be married to boring, stable Franz, at the same time, there will be her involvement with the Crown Prince, son of Francis Joseph. Hans will be sent off to the front during World War I, will be captured, imprisoned, and after he is finally freed, "His eyes were still full of the things he had had to look on." (The author does not tell us what "he had to look on," but knowing what we do about WWI, and the overall treatment of POW's, the author doesn't have to be too specific.)

Characters out of history continue to dance though the story. There will be the Workers' strike of 1910, which our piano workers join. Henriette will be loved by the son of the Emperor. Hans will be in art school with an angry, shabby man with yellow fingernails and bad teeth, a man they call Hitler. Hans will also study at the University with Laurence Mueliner

where none of the hard-drinking rowdies ever strayed, and to discover that there is no such thing as chance, but that everything which had been created or had occurred is obeying the law of necessity!

He will visit his grandfather's clases in constitutional law, where "he assigned to the state the part of service and to the people in the state the part of governing." And finally, he will study the Analysis of Dream Life, by one Professor Freud, where in the classes "he experienced at first an almost physical revulsion; the very theme of them seemed to him to be a constant infringement of his sense of modesty."

Later, he succumbed to the personality of the lecturer, whose whole teaching radiated the inner purity of his diagnostic fantasy and lucidity.

"For the first time he was not obliged to accept teachings as something already proved, but he could be a helper and a witness in the process of their creation."

It is this occasional flight of language that captures us as we go through lives of this family, which will, during the course of The Vienna Melody, create a murderer, frame a martyr, involve one character in a fatal duel, bring an acclaimed actress into the house --- she plays George Bernard Shaw's Saint Joan --- and finally finds Hans becoming a constant companion to Austria's Chancellor Dollfuss just before he is murdered by the Nazis.

Through it all, the theme of those who live there at #10 Seilerstätte comes to be understood, clearly, by Henriette:

That's what comes of it when you do control yourself! thought the widow of the piano-maker Alt. That's what comes of systematic hiding, minimising, denying, renouncing. What a mortal fallacy! One cannot be happy if one hides one's feelings. Nor can one make others happy.

If we are left with one thing after our four-day marriage to this book, it has to be the book's powerful sense of what makes Vienna Vienna, a place that could and does contain such fine intellect, such beauty, such music and harmony. The house is deeply involved: the Alt factory provided Mozart with his first piano; Henriette may have caused Francis Joseph's son to kill himself; Hans studies with the Inventor of the Superego; after the murder of his friend Dollfuss, Hans and Henriette go to the Vienna Opera House to mourn with Verdi's Requiem.

§ § § The Austrians are no nation. They make up twelve odd nations --- that is, none at all. If an Austrian speaks German as you and I do he considers himself the Austrian and imagines meanwhile that the Czech or the Italian or the Pole feels just the way he does, proud of Vienna, the Imperial City, of Mozart, of the waltzes and the local wine. Ridiculous! The Pole in Przemysl or the Italian in Trient or the Bohemian in Budweis has no other thought in this head but the one: How am I to get out of this infernal prison where my own language is not the "official language" but a second-rate Hindu dialect, where I have it dinned into me from morning to night that I am a third-rate creature, and yet where they force me to serve for three years in the army and to pay taxes all my life for the first-class creatures, the Viennese?

And, "I never under any circumstances whatsoever want to be anything but an Austrian. When my train pulls into the Anhalter station in Berlin exactly on time, and I am offered the first fruits of German thoroughness, my stomach turns, and I long for our own sloppiness. When I go to the opera in Paris I bless every Viennese box usher. I thumb my nose at American civilization where they shoot into the sky in an 'elevator' and with their skyscraping civilization smother culture."

Our Emperor is a disgrace. He actually said to an American President, "You see in me the last monarch of the old school," and was proud of the disgrace! For that old school of monarchy was firmly convinced that it was the duty of subjects to sacrifice themselves for the dynasty instead of the other way round.

This is a novel of the old school. It takes time and it takes your time, and in it you get to live many other lives, seeing the world as they saw the world, growing up and growing old and regretting the decisions we forced ourselves to make, sometimes hating those we love (and even not loving but perhaps understanding those we should hate). People get shot, die, turn stupid, fall in love, and turn around and shoot themselves in the foot and want to kill themselves . . . and then going off to the Vienna Staatsoper to hear Verdi's chorus there under the resolutely disciplined conducting of Toscanini: this, one of the saddest operas (misnamed Requiem) ever penned, to compete with our grief over today's dark gray depression, tomorrow's springtime walk down the Schlossstrasse (under its gorgeous sycamores); then next week's worker's noisy headbashing strike, and next month's excellent rendering of von Hofmannsthal's Elektra and next year's declaration of war . . . and finally next century's reinvention of our lovely Vienna. And all the while we're thinking "I'm proud of Vienna, just because of that senile Francis Joseph, proud of his being the last monarch of the Western World, the monarchy soon to disappear forever. We must be proud of this ridiculous place, no? --- with its ridiculous history, its ridiculous characters, its romantic nonsense, and that ridiculous music --- The Beautiful Blue Danube indeed!

Of course I'm proud! Who else in the world could possibly accept, even show off all this, I ask you?

Unlike any place else in the world . . . who would ever consent to submit to all this, outside of those of us romantic tragedians who presume forever to live here?"

--- Ellis Esbenshade