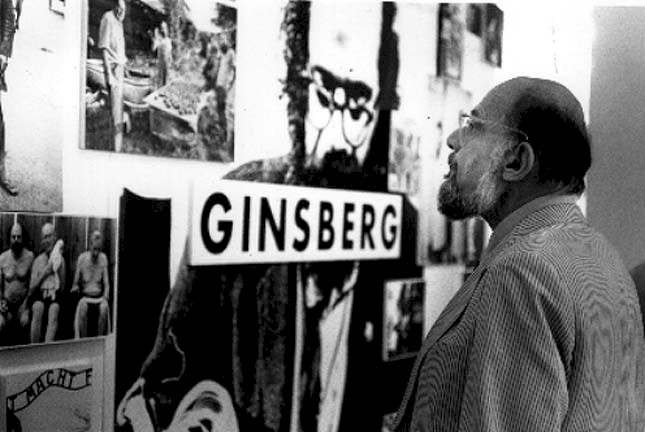

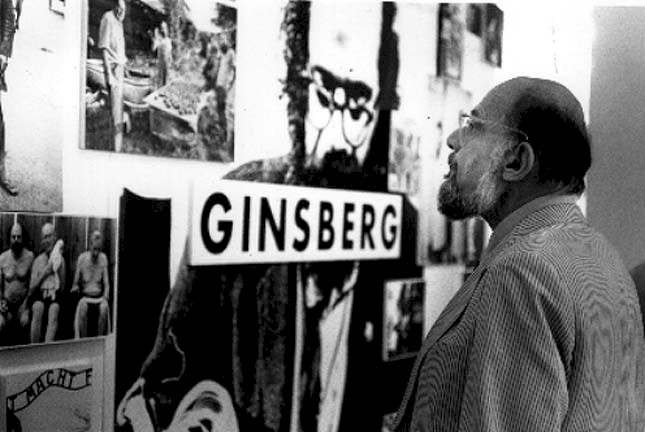

The Essential Ginsberg

Allen Ginsberg

Allen Ginsberg

Michael Schumacher, Editor

(Harper Perennial)

The Essential Ginsberg has thirty-four of his poems, three of his songs, along with ten essays, seven journal pieces, two interviews, twelve letters, and sixteen of his photographs. If I were you, I would jump at once into the interviews.I had always figured that Ginsberg was a funny, dreamy, acid-soaked hairy, semi-mystic bearded guy who was constantly sticking his index finger into the ribcage of American sententiousness, trying to get people to laugh a bit over their own Americaness. I had read Howl from time to time, but it wasn't until I heard him read it that I began to get the picture. As I wrote in the review,

It's flat-out exhausting, gripping, funny. It takes a few lines for Ginsberg to get himself cranked up, but then, all pistons going, it drives itself (and the listener) beyond the horizon, beyond reason.

I also recalled that "Ginsberg never lost his touch, neither in his writing, nor in his life. His public self was his persona, but that never stopped him from being Allen Ginsberg. He was not only a man of wit, he had a daring: once on a visit to Cuba, he demanded that Che Guevara dance around a maypole with him."

This last comes to have special poignance when we read in The Essential Ginsberg his Havana journal entry from 1965. He's trying to sleep and at seven a.m. they are pounding on his door, "three soldiers in olive green neat pressed uniforms" who have come to escort him to an airplane that will fly him off to Prague, to get him the hell out of Cuba long before he was scheduled to leave.

The joke is that all he can think of as they are hustling him to stop standing around in the buff so they can get him packed and off to the airport . . . he's thinking about his journal and all that he has written of some of the lusty sessions he had had there in Havana with lovely young Cuban men during the last week so he keeps stuffing the notebook down to the bottom of his bag hoping these uniforms will not find it and read it and take it to their jefes and punish the kids for all the lovely things they did together with Ginsberg knowing as he did that Latino Marxists are not especial fans of gay love. (They never asked to see the black book; they just wanted him the hell out of there.)

Before the uniforms get him stuffed into the airplane there was some back-and-forth with the Chief of Immigration because Ginsberg was understandibly miffed at being shipped off a rush job to Czechoslovakia all while he was planning a few more weeks in the sun doing readings of his poems and drumming up some more burnished buffed-out young men there on the playa. He asks repeatedly why he is being deported, and Captain Immigration (Carlos Varona) replies that it had something to do with Ginsberg's "lack of respect for our laws."

"But what laws?"

"Cuban Laws . . . just basic immigration policy . . . also a question of your private life . . . your personal attitudes . . . "

"What private life --- I haven't had much of that since I've been here." I laughed, so did he.

And then later,

I sat back. Relieved really, it was only the airport, for Prague, not a jail or interrogations about the boys or pot or gossip or Che Guevara's narcissism from Argentina.

For those of us fascinated with poets and poetry one of the interviews that appears here is a treasure, a gold mine, a wonder, a seizure of mad joy, a poke in the hole of those PhD's who have managed to strangle the babe of verse in its crib (or maybe better shove the bastard into the grave long before it is time for it to retire from the scene). Since before this I had more or less seen Ginsberg as a merry goofball, had him figured for a dilettante, it was a surprise to find that he knew his stuff. In the June 1965 interview with Thomas Clark for The Paris Review, once Ginsberg finally shakes Clark's rather cloutish questions, gets into what poetry does, should do, always will do . . . we find ourselves floating on the cloud of his words, being astonished that he is just sitting there conversing (presumably without notes) and still can come up with so many knife-in-the-heart insights about poetry.

In an hour or so he brings up not only the favorites you would expect --- William Burroughs, Ezra Pound, William Carlos Williams, Gregory Corso, Michael McClure, Charles Olson, Philip Roth, John O'Hara, Jack Kerouac --- but, as a bonus (and not just name dropping) offering Whitman, Keats, Blake, Shakespeare, Coleridge, De Quincy, Bob Southey, the King James Bible, Dostoevsky, Thomas Wolfe, Rimbaud, Verlaine, Saint Thomas Aquinas, and most fascinating, Cézanne.

In fact, Cézanne and Blake are, as he phrases it, the two artists who knew it "was possible to transmit a message which could reach the enlightened."

The impression I got was that it was like a kind of time machine though which he could transmit his basic consciousness and communicate it to somebody else after he was dead --- in other words, build a time machine.

Who else besides Ginsberg, I ask you, could make that frantic awesome transition and see vital art as a "time machine." And it just isn't half-baked assumptions about Cézanne because Ginsberg went off, went to the trouble of researching the art and the artist, goes off to Aix, tried "to find the places where he painted Mont-Sainte-Victoire," then went to his studio, "it was like an alchemist's studio, because he had a skull, and he had a long black coat, and he had this big black hat." And then he quotes the painter, "I use these squares, cubes and triangles, but I try to build them together so interknit [and here in the conversation he held his hands together with his fingers interknit] so that no light gets through."

Here I found myself caught up in what Ginsberg was saying because I suspect what he came to see in Cézanne was close to something that had come to me about the same time:

And I was mystified by that, but it seemed to make sense in terms of the grid of paint strokes that he had on his canvas, so that he produced a solid two-dimensional surface which when you looked into it, maybe from a slight distance with your eyes either unfocused or your eyelids lowered slightly, you could see a great three-dimensional surface opening, mysterious, stereoscopi, like going into a stereopticon.

I figured here that Ginsberg had been reading my notebooks, dipping into my epiphanies. For at exactly the same time as he got his own three-dimensional vision whammy, I was getting what my teacher identified as a "fleshing out," one that had came to me in a course I was taking in Philadelphia. (In my case, the epiphany came from a rather small painting of one of Renoir's milk maids where I watched a young and roseate farm-girl looking out at me while she brazenly poked her elbow right out of the canvas into my face, as if saying "Here, buddy: you want art. I'll give it to you. Right in the schnozzla.")

But it just isn't painting and Cézanne that lights up Ginsberg's interview. At one point he gets onto juxtapositions of words which he views as comparable to Cézanne's juxtaposition of colors, but, for a writer, the same . . . with words, with what he calls "the gap between words which the mind would fill in with the sensation of existence."

When Shakespeare says, "In the dread vast and middle of the night," something happens between "dread vast" and middle." That creates a whole space of, spaciness of black night. How it gets that is very odd, those words put together. Or in the haiku, you have two distinct images, set side by side without drawing a connection, without a logical connection between them the mind fills in this . . . this space. Like

O ant

crawl up Mount Fujiyama

but slowly, slowly.Now you have the small ant and you have Mount Fujiyama and you have the slowly, slowly, and what happens is that you feel almost like . . . a cock in your mouth!

"You feel this enormous space-universe, it's almost a tactile thing . . . it's a phenomenon-sensation, phenomenon hyphen sensation, that's created by this little haiku of Issa."

§ § § I have said that the two interviews here are a treasure-chest, filled with surprises like this one . . .

. . . or like the casual mention of the fact that he once went to interview Martin Buber. Just like that: "In Jerusalem, Peter and I went in to see him --- we called him up and made a date and had a long conversation. He had a beautiful white beard and was friendly; his nature was slightly austere but benevolent."

Peter asked him what kind of visions he had and he described some he'd had in bed when he was younger. But he said he was not any longer interested in visions like that. The kind of visions he came up with were more like spiritualistic table-rappings. Ghosts coming into the room through his window, rather than big beautiful seraphic Blake images hitting him on the head.

"Melt into the universe, let us say --- Buber said that he was interested in man-to-man relationships, human-to-human --- that he thought it was a human universe that we were destined to inhabit.

"And he said, 'Mark my words, young man, in two years you will realise that I was right.'"

This was like a real terrific classical wise man's "Mark my words, young man, in several years you will realize that what I said was true!" Exclamation point.

And I am thinking that in 1961, Allen Ginsberg went with his lover to Jerusalem, and called up Martin Buber, and said he would like to come over and chat with him, and Buber said OK, and so the two of them went over to Buber's house, and they sat and talked with him, and Buber said, "Mark my words, young man." And he did and it was and it was true. And you read it here.

--- L. W. Milam