are not for the classic reviews, wonderful readings, or fascinating articles ---

but for the photographs and drawings we use to accompany our text.

Here are twelve shots that are called up most often,

along with their appropriate writings.

Now Praise

Famous Men

James Agee

Walker Evans

(Houghton Mifflin/Mariner)

With these two, we are there, in Hobe's Hill, Alabama, in the hot summer of 1936. It is a writing that is cumulative, exactly defining a piece of furniture, or defining one odor, then another, then reweaving them together, then accumulating yet another. It becomes, in Agee's hands, poetry and music, for music appears regularly as a counterpoint to the words, when he tells us to "lie on the floor" and subject ourselves to the pain and the beauty of it.It's serious stuff, but, too, Agee sprinkles a few jokes around here and there --- such as taking time off (he calls it an "Intermission") to excoriate the editors of Partisan Review for a questionnaire on "art." Or in the beginning "Persons and Places," he lists all members of the three families, then,

James Agee: a spy, traveling as a journalist.

Walker Evans: a counter-spy traveling as a photographer.And as "unpaid agitators,"

William Blake

Louis-Ferdinand Céline

Ring Lardner

Jesus Christ (referred to earlier as "a dirty gentile")

Sigmund Freud

Lonnie Johnson

Irvine Upham.Agee says at one point that he would prefer it if people would read the book aloud. With its heavy Biblical overtones, with its beautiful circular writing, with its poetry, and music --- it becomes a classic of American literature, as important (in its eccentric way), as Winesburg, Ohio, Huckleberry Finn, The Catcher in the Rye, The Great Gatsby, The Sound and the Fury, A Farewell to Arms. It is high time that it is rediscovered, and the publishers deserve thanks for bringing it back in this fine edition.

Go to the complete

review

World War I

In 100 Objects

Peter Doyle

(Penguin)

It is certainly odd what people will fabricate to disembowel each other, especially in times of war. There is (or was, for World War One) exotic hardware --- bombs, rifles, machine-guns, flame-throwers, gas projectiles, howitzers, Very lights, mortars --- you name it.Author Doyle has here come up with several dozen oddities to make WWI out-of-this-world, or at least take it away from the trenches. Alpine crampons for fighting in the mountains between Austria and Italy. A special Ottoman belt buckle for the Turkish soldiers serving in the Mediterranean, with red fez (they were known as "Johnny Turk" by the Brits). Liverpool "Pals" --- special badges for the recruits from one area (usually poor dogsbodies from the lower classes) who signed up together, coming from the same town or neighborhood.

There was a postcard circulated in France called "Les Poilus" showing three soldiers --- quite hairy, thus the name --- that were said to represent the common man in the field. There was the common puttee, a nine-foot reinforced strip of cotton or wool wrapped from ankle to knee to protect against the bitter cold (and the ever-present mud) in the trenches. A Wolseley helmet --- what we would later called a pith helmet (another gift of colonialism) --- that came into being during the Boer War and was vital protection in WWI against the sun in the southern battlefields such as Basra and Baghdad. Who'd ever guess we'd get to meet these names again, a mere 100 years later: love may come and go, but the love of war, and its impedimenta, never disappears. Thus this book.

Go to the complete

review

E. O. Hoppé's

Amerika

Modernist Photographs

From the 1920's

Phillip Prodger, Editor

(Norton)E. O. Hoppé came to America in 1919, immediately after World War I, intent on setting up a studio to photograph the rich and the prominent in New York City. At times, he also slipped out of his studio to study "the down and the out," the poor people of the Bowery and the Lower East Side.He stayed in this country for two years, returned to Europe, then returned, eventually taking his camera through the northeast, the south and the far west, photographing people, natural landmarks, and industrial America.

These "modernist" pictures make an unusual juxtaposition of horizontal and vertical lines: overhangs, wires, transmission towers, with an artful perspective. Hoppé used a wide-angle lens, one that made it possible to join the distant and the close-at-hand without losing focus.

The editor of this volume suggests that the pictures made in New York, Boston, Chicago, and the manufacturing centers of the middle west are composed much as "a shift supervisor might see them: a cascade of forms in chaotic rhythm, punctuated by the steel beams of the vertical." The majority of the 150 photographs in this volume are what you might label as "Industrial Bleak." But as Marshall McLuhan would have it, the products of yesterday's factories --- indeed, the very factories themselves --- will become tomorrow's antique icons. So it is with these shots of conveyer belts in Detroit, the industrial slums of Alexandria, the Woolworth Building in New York City, the new, uniform suburbs of 1920s west coast America.

Hoppé shows a magisterial hand. He sets his camera perfectly to insert a cross-purpose in every scene: steel beams going that way, transmission lines going this, a roof over there. It is a photographic style that is both architectural and subtly transforming. The stockyards of Chicago reveal a crisscross artistry of light and shadow. The pictures of factories, cityscapes, and buildings chosen for inclusion in Amerika outnumber the studies of faces, but the latter are daring close-ups: faces of beggars, farmers, the poor, blacks, and American Indians [see "Yakima Indian, 1926" above].

Go to the complete

review

The Klondike Quest

A Photographic Essay: 1897 - 1899

Pierre Berton

(Boston Mills Press)There were three ways to get to Dawson in 1898: up the White Pass Trail, up the Chilkoot Trail, or down the Yukon River from Alaska. It is estimated that 80% of the stampeders went via the passes, the other 20% by way of Alaska.The impetus, according to Berton, was not so much gold fever as the fact that the United States was --- in the midst of the so-called "Gay 90's" --- engulfed by a panic. That was the word in those days for what we now name "economic depression."

There was nothing gay --- in the older sense of the word --- about the journey. The White Pass was called "The Trail of Dead Horses" because 3,000 horses died en route. Chilkoot Pass was scarcely better. But the worst impediment to the stampeders was not so much the weather, which was dreadful, nor the passes, which were almost impassable --- but the Canadian government.

The route north to Dawson was in the hands of Canada, although uneasily so. The U. S. claimed part of the Klondike, but was busy fighting the "white man's burden" at other venues ... namely Cuba and the Philippines. It was not free to make war on our neighbor to the north.

There was a rule, a sensible rule if you think about it, enforced to the hilt by the Northwest Mounted Police. The rule was that if the stampeders were going into a place of ice, snow, trees, and nothing else, that they could not enter "without a year's supply of provisions."

To get a year's worth of provisions to the mountain top --- assuming fifty pounds per trip --- required forty trips.

Exhausted by the climb --- filthy, stinking, red-eyed, and bone-weary --- each knew that this was but the beginning, that he must go down again and up again, again and again, and again, until he had checked it all through the Mounted Police post at the border: bacon and tea, flour and beans, clothing, tents, stove, sledge. There were no hardware stores on the far side.

So up they went, again and again, doing what came to be called the Chilkoot Lockstep, "an odd rhythmic motion" that, according to Berton, none would ever forget. Nor would they forget another weird experience, the moan:

In the years to come one sound would continue to echo in their memories --- the single all-encompassing groan which, as one the White Pass trail, rose from the bowl of the mountains, like the hum of a thousand insects.

Go to the complete

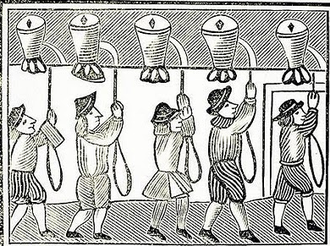

reviewSinging Bronze:

A History of Carillon Music

Luc Rombouts

(Lipsius Leuven)

- In the Divine Comedy, Dante wrote of the earliest carillons, which had come into being in the 13th Century. It was said that they produced heavenly sounds, tin tin sonando consì dolce nota.

- The first clock carillon was built around 1400 in the monastery of Windesheim in the Netherlands, where Brother Hendrik Loder constructed one with seven bells which would ring out a "Gregorian sequence Sancti Spiritus Adsit nobis gratia to wake the monks and place them in the appropriate state of mind."

- For the first time, the "lapse of time" gave Europeans "a new experience of day and night." Since bells were struck not by machine but by hand, those hands had to depend on a clockless world.

- The hardest of the lot was Matins, to be struck at midnight. "The bell-ringing monk could not use a sundial. Moreover, he himself needed an audible signal to wake up." Problem solved: the water clock, which at around 11 or 11:30 would lurch into action and waterboard the monk. I just made that up . . . silly me. No: the water clock "sounded the bell at the appropriate hour."

- Escapement came to rescue the sleepless monk in the form of a weight suspended on a rope, with an escape wheel, a vertical gear. As Rombouts says (nicely), "Time had become music, and thanks to the new forestroke, the abbey more than ever was bathed in the aura of the sacred."

- Much is made of the difficulty of casting bells. If you only had one, there was no problem, for there was nothing else around for the sound to compete with. But with carillons, there was the exasperating necessity of having the bells talk to and agree with each other . . . and not go jangling off in some minor third that had nothing to do with the tonic fifth, the major ninth, and all that other elegant finery in the musical world of these noisy clappers.

Go to the complete

reviewMoko Maori Tattoo

Hans Neleman,

Photographer

(Edition Stemmle)It's a question of face, isn't it? --- "the face we prepare to face the world." It is the part of us that presents the Me to all the other Me's.Many women of the west paint their lips and cheeks, shade their eyes and eyelashes, hang decorations from the ears. This is supposedly to enhance one's beauty, make one more interesting or desirable. But if I am Hindu, a third eye painted above the bridge of my nose is not for sensual purposes, it, instead, tells the world of my religious beliefs.

Contrariwise, if I am a young American, sticking pins in the eyebrows, a jewel through the nose, a ring in the lips --- I am showing all who meet me that I am different, and that I am willing to go through pain to assert that difference.

All these have one element in common: the third eye, the lipstick, the rings can all be removed. But there is no going back with the facial tattoo of the Maori. It is a painful process of design which states publicly one's passionate belief in one's people, and their ways, and their religion and history.

These photographs, almost a hundred in number, are a wonderful peek at a culture of artful difference. Some of the tattoos are delicate, understated. But some are a poke in the face, so to speak, at the world. Sinn Dog's decoration, running across the lower half of his face --- like a mask --- including nose, lips, cheeks and chin, proclaims MONGREL FOR LIFE. He is an ominous-looking dude, with or without tattoo. Meeting him in a bar, I would suspect most of us would speak to him with caution and some care. His life-time sign, right there before your eyes, says it all.

Go to the complete

review

George Rodger

An Adventure in Photography

1908 - 1995

Carole Naggar

(Syracuse)He's not handsome, this weeping man --- not beautiful. But there can be no doubt that this proper, well-dressed man is grief-stricken. More than those behind him, he seems to know what will happen to his city, to his life, to his world over the next four years, for he is standing on the streets of Paris, in 1940, watching the Nazis march in.There are no words necessary. The photograph tells it all.

I've often wondered about the photographer who took this astonishing shot. What did he think? What did he feel? Did he worry about invading a man's sacred space? Did he think that because he was behind a camera he had a right to extract, even gain from another man's grief? Was he weeping too? Did he excuse himself for intruding himself on the man's sorrow (capturing a sorrow that can --- even now --- capture the rest of us?)

Every time I look in the newspapers or magazines or on TV and see just such a picture --- a woman after her son has been murdered; the face of a man whose son has died in the military service; a granny who has been divested of her home by some charlatan --- I think of the photographer who suddenly appears on the scene and without permission envelops someone else's tragedy, stealing it for his own.

Rodger had an answer before he went to the concentration camp. He was creating art. He even described the photos he took at Bergen-Belsen "artistic compositions." He was working, he wrote in his journal, with "honesty," "clarity," "simplicity of purpose."

But something else happened inside of him. Rodger permitted himself to be interviewed but once about his experience, towards the end of his life, in The Guardian.

This natural instinct as a photographer is always to take good pictures, at the right exposure, with a good composition. But it shocked me that I was still trying to do this when my subjects were dead bodies. I realized there must be something wrong with me. Otherwise I would have recoiled from taking them at all. I recoiled from photographing the so-called "hospital," which was so horrific that pictures were not justified ... From that moment, I determined never ever to photograph war again or to make money from other people's misery. If I had my time again, I wouldn't do war photography.

As Naggar reports, "Photographing at Belsen was for Rodger a personal disaster. It triggered a guilt even greater than that he usually harbored, as if being a witness to horror, and taking pictures of it, was something unspeakable and forbidden. As if it somehow made him an accomplice. He was so traumatized by Belsen that for the next forty-five years he could not bear to look at the pictures he had made there and wished he could erase them. Yet Belsen resisted being forgotten."

Go to the complete

review

Chernobyl

The Hidden Legacy

Pierpaolo Mittica

(Trolley Books)The facts are now well known. Nuclear reactor number four exploded on 26 April 1986 at Chernobyl, in the Ukraine. The radiation levels in the worst-hit areas of the reactor building have been estimated to be 5.6 roentgens per second which is equivalent to more than 20,000 roentgens per hour. A lethal dose is around 500 roentgens over 5 hours. Clouds of radioactive dust swirled across Russia, into Sweden and Norway and parts of England, and ultimately through the world (even areas of Canada and America were affected by May 6 of that year). Belarus was the worst hit, with 30% of its area contaminated, "stretching over 260,000 square kilometers of land (almost as large as Italy.)" It will, reports Mittica, "return to normal radioactive levels in about 100,000 years time. Almost 20 years have gone by, so we have another 99,980 to go."500 villages and settlements were evacuated, "out of these more than 100 have been buried forever."

At the present time nine million people in Belarus, the Ukraine and western Russia continue living in areas with very high levels of radioactivity, consuming contaminated food and water.

"There has been an increase of 100 times of the incidence of tumors of the thyroid, 50 times in other radiation-related tumors, such as leukemia, and bone and brain tumors."

Chernobyl is not the past. Chernobyl is not history. Chernobyl is the beginning.

Go to the complete

review

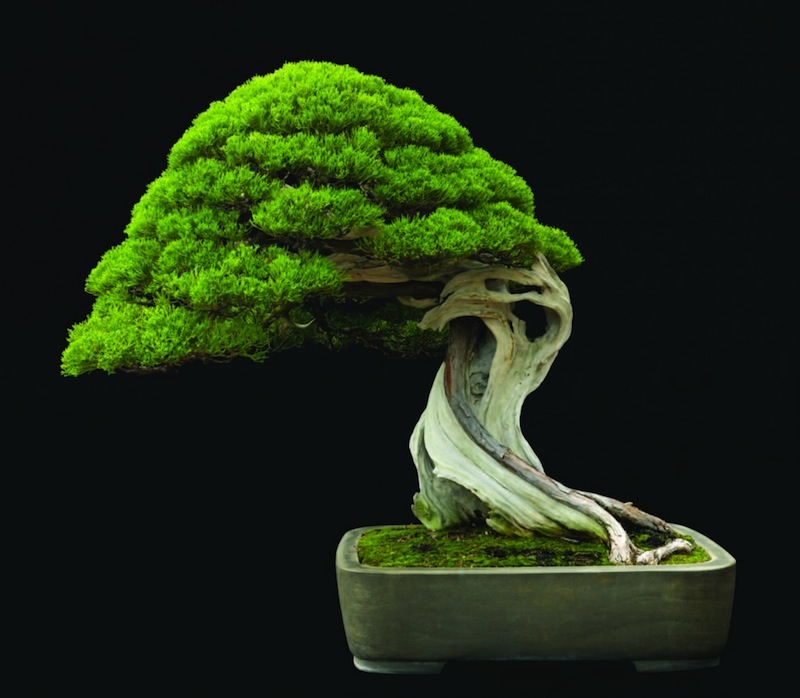

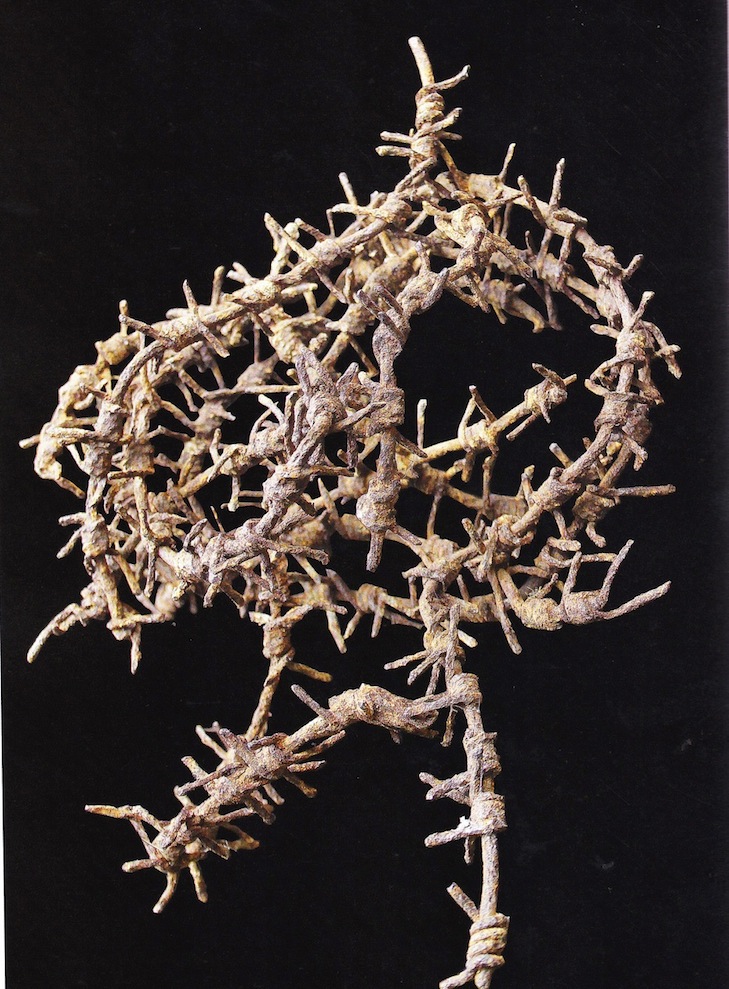

Fine Bonsai

Art & Nature

William N. Valavanis

Jonathan M. Singer, Photographer

(Abbeville Press Publishers)So here we have a scandal finally revealed in this elegant volume. Instead of being titled Fine Bonsai, it might well have been named Abusing Your Cedar. An artist by the name of Shen Shaomin has documented the brutalities inflicted on these inoffensive plants. Shaomin's on-line illustrations show the machinery by which these plants are forced into bizarre positions, shapes and configurations. "Wire cable, clamps, metal plates are used to 'torture' each bonsai tree into strange positions," he writes. His images are shocking: he shows twenty-two tiny instruments of torture (pliers, twisters, cages, splints, scrapers and points) that are used on a benign hinoki cypress, an innocent black pine, a gentle border privet, a shy juniper. Then there is an oriental photinia, an unassuming red-leaf hornbeam, a bashful trident maple, a frail japanese beautyberry, a quiet firethorn, a hoary hornbeam, a lonely Japanese snowbell cedar or black pine shown forced into confinement in a teeny pot with scarcely room for its crowded little roots ... constantly being jabbed and punched and trimmed and twisted, perhaps even being scolded when it tries to escape its little prisons.The American Nurserymen's Association should take action at once, report the widespread abuse aimed at these innocent plants who have, we are certain, done no wrong. We suggest, no, we demand that The Ladies Garden Clubs of America, The Men's Garden Clubs of America, The National Association of Flower Arrangement Societies, The Future Farmers of America and all 4-H Clubs unite to take arms, rise up in force, move into action --- issue a trumpet call to save our trees from what we now know to be Bonsai Bondage.

We plant lovers should unite, too, to praise Abbeville Press for issuing this manifesto --- a ten pound "J'accuse," a call to arms --- citing these who are, as we speak, inventing new tortures for these innocent plantlings, whose only crime is that they tried to Grow Free ... but are now subject to treely bondage, forbidden the height they deserve, kept down by these arboltrary masochists.

All they are asking --- and all we should ask for them --- is that they be permitted to stand tall once again, with dignity and justice for all.

Go to the complete

review

My Black CatMy black cat gave birth last night

Four and five make nine-o ...

One of them had deep blue eyes

Eyes as pretty as mine-o.Mother said that they must go

Drown them in the well-o ...

So I hid the little one in my shoe

The one with eyes like mine-o.--- Clare Marx Arce

Freud:

A Very Short

Introduction

<Anthony Storr

Neville Jason, Reader

(Naxos AudioBooks)Civilization and Its Discontents, the Wolf Man, the Rat Man, Anna (and Anna O!), penis envy, the Oedipus Complex, the Electra Complex, The Interpretation of Dreams, cigars, Charcot, Fleiss, hysteria, infantile sexuality, jokes, the unconscious, neuroses, slips of the tongue, the oral, the anal, and death. It is astonishing what the man accomplished in his almost eight decades on earth.At one point, Storr wonders out loud why Freud was so influential. He cites his marvelous writing style (and it is wondrous, even in translation --- Norman Mailer said Freud was one of the greatest novelists of the 20th Century). But we suspect it is more simple than that.

Most of us want to know what makes us tick, and most of us run into people and events that affect us strangely, that make no sense. We wonder where they come from, what it all means, how could we --- for example --- fall into a trap, any trap, that trap again.

Positing id, ego, and the hidden unconscious gave us a chance to explain these oddities. For those lucky enough, or rich enough, psychoanalysis offered the chance to peer into one's own mind with the assistance of a nonjudging, tolerant, and infinitely patient helper.

Storr was a practicing psychoanalyst, which would mean that he should also be patient, observant, non-judgmental. In writing about Freud, he is patient and observant but very judgmental. He wants to make sure that we know that when Freud defined the obsessional character ("order, cleanliness, control") the master was talking about himself: a man of detail, one who was detached, one who did not brook rebellion in the ranks.

Storr suggests that although Freud repeatedly called his handiwork a science --- not a philosophy, not a religion --- those who deviated from the dogma (Fleiss, Jung, Rank) were cut off, even labeled by the other followers as "Neurotic" or "Psychotic."

Go to the complete

review

Stieglitz

Steichen

Strand

Masterworks from the

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Malcolm Daniel

(Metropolitan Museum of Art/

Yale University Press)Georgia O'Keeffe might well have been included in the title of this book because Stieglitz took more than three-hundred photographs of her during his long career. Sixteen are included here, including her face, hands, feet (pretty gnarly), toes, breasts (beautiful), backside, frontside (gorgeous!), throat ... with several additional pictures of her staring at the camera (and the photographer) (and us) and doing her hair and caressing the hubcaps of her Ford V-8 and, also, fondling a horse skull. Which is OK by me because I have always found the camera art of her body and her personality far more engaging than those strange paintings of flowers looking more like intimate body parts than tulips and begonias.Steichen was like Stieglitz and if you get their names confused I am with you because I can never remember who is who nor who has the "i" before "e" (but not after "c.") Steichen also did the misty bodies/wind-blown hair/faceless-faces in space and four of these turn up here reminding us not so much of the Impressionists (of whom he was fond, so fond that he shot photographs that look like they just busted out of Manet's paint-studio).

Steichen was also much taken with Auguste Rodin and especially that corn-ball statue "The Thinker" which when I was in grade school whenever someone assumed the same pose we inevitably dubbed him "The Stinker." Rodin's statue in honor of Honoré de Balzac is even cornier but evidently those who put this volume together thought enough of it to include three shots Steichen made of it at 4 A.M., 11 P. M., and midnight. These three are included here as an overleaf which must have cost a small fortune in the production of this fine volume but when you open up the set they appear impressive enough although god knows what that statue has to do with the novelist though it has been said that Balzac's figure was so gargantuan that the sculptor chose to drape him in robes because that was the only way that Rodin could do him justice without making a comic figure out of him ... a statuesque Oliver Hardy or Falstaff.

Go to the complete

review

Lightning

A Novel

Jean Echenoz

Linda Cloverdale

Translator

(The New Press)Gregor is a genius, but a bit peculiar. He doesn't like being touched. He thinks the number three is very important to him. He can go for days without sleeping. And he is not at all smart about finances. J. P. Morgan offers him a contract that would have made him rich (it has to do with generating electricity) but Gregor tears it up because he wants power to be free for all the people. His patent for radio --- #645576 --- is poorly drawn, and Sr. Guglielmo Marconi stakes his claim and hits the jackpot. Gregor works with Thomas Edison, who offers him a bonus for his efforts, but Edison laughs when he tries to collect. Gregor offers his ultrasonic listening device to the military, but they yawn. (Later it came to be known as radar).In fact, according to Echenoz, Gregor is only successful with his first invention (alternating current), with the ladies (he's not interested) ... and with pigeons.

Pigeons? He spends the last years of his eighty-odd years on earth caring for street pigeons from New York City, smuggling them into his dusty hotel room (he has installed tiny pigeon cages, with tiny pigeon showers), eventually developing "a secret bond" with one --- giving her the love he could never offer to the women who were always interested in him.

His reward? Do the pigeons thank him? Do they care for him? Nonsense: in Gregor's world --- where everyone screws Gregor --- the pigeons screw Gregor. One winter evening, as he goes out for his evening walk, the pigeons fall en mass upon the windshield of a nearby cruising Dusenberg, blinding the driver, who runs over Gregor. He is done for.

Go to the complete

review

Art

Over 2,500 Works from

Cave to Contemporary

Foreword by Ross King

(DK) Art offers an interesting take on a way to look at paintings: look at the patterns; follow the lines; recognize the balance of elements. But don't look at Art for the art. It will never be the be-all because great paintings have to be seen as they are, not as they are reproduced. We have here massive art works reduced down by 90 - 95%, leaving only hints of what we are missing.

Art offers an interesting take on a way to look at paintings: look at the patterns; follow the lines; recognize the balance of elements. But don't look at Art for the art. It will never be the be-all because great paintings have to be seen as they are, not as they are reproduced. We have here massive art works reduced down by 90 - 95%, leaving only hints of what we are missing.And, that is, perhaps, the value. For you will see --- among the more than 2,500 paintings, drawings, sketches, sculptures, buildings shown here --- something that grabs your attention, something that, if you are lucky, will lead you to the source.

Wine glasses by Patrick Caulfield. The original Laocoön, the three figures enrapt by those snaky snarky creatures. Arabesque tilework --- which I must have on my dormer wall --- from at the Masjid-i-Jomeh mosque in Isfahan, Iran.

A windblown horse with groom, by Zhao Mengfu, now resting in Taipei. Bellini's very prissy Doge Leonardo Loredan. Giotto's very green Christ in Florence. Françoise Rude's very rude Liberty. Boccioni's very husky Unique Form of Continuity in Space [See Fig. 1 above].

Hokusai's famous and stupendous wave, cresting at the British Museum. Van Gogh's colorful, lovely, tiny, lively bedroom at Arles, now no longer in Arles, but in Chicago. Richard Bergh's stately Nordic Summer Evening complete with a dim Nordic sun, hidden, hanging hidden there in the Goteborgs Konstmuseum. Rousseau's leafless walk in the forest. And ... Lord Love Me ... Modigliani's stupendous Nude with Necklace, the nude (and the necklace, some necklace!) hanging together now at the Guggenheim in New York, where, some day soon, before I pop off, I must, somehow, get to see.

Go to the complete

reviewHummingbirds

Ronald Orenstein

(Firefly Books)There may be a brighter day for the patagona, because its days as the hummingbird gargantua may soon be over. This change has been brought about through studies of the common ruby-throat. Because of its extensive range, we've learned that it has to store up energy as fat . . . almost doubling its weight. This fact has led to the recent success of Japanese scientists to selectively produce ever-larger hummingbirds. By inbreeding, conjoined with Jack LaLanne-type exercise programs, ornithologists at Kobe University have recently created our first 65-pound hummingbird.Named Tubby the Terrible for his phenomenal girth (and miserable disposition), this fugitive from the gland gang can, unfortunately, no longer twitter, but merely groan. However, Tub uses his weight to get what he wants. When he spots another male hummingbird trying to pinch his poke, he sits on the sucker until he cries uncle.

Still, this bovine ruby-throat can barely fly, and has trouble moving about at all. It was perhaps in anticipation of this obese creature that Fats Waller composed his famous lyrics for "Your Feets Too Big,"

Oh your pedal extremities are colossal

To me you look just like a fossil

You got me walkin', talkin' and squawkin'

'Cause your feet's too big, yeah

Come on and walk that thing

Oh, I've never heard of such walkin', mercy

Your, your pedal extremities really are obnoxious

One never knows, do one?Go to the complete

reviewFinding a Lion

In Your BedroomTowards the end of my stay in British East Africa, I dined one evening with Mr. Ryall, the Superintendent of the Police, in his inspection carriage on the railway. Poor Ryall! I little thought then what a terrible fate was to overtake him only a few months later in that very carriage in which we dined.A man-eating lion had taken up his quarters at a little roadside station called Kimaa, and had developed an extraordinary taste for the members of the railway staff. He was a most daring brute, quite indifferent as to whether he carried off the station master, the signalman, or the pointsman; and one night, in his efforts to obtain a meal, he actually climbed up on to the roof of the station buildings and tried to tear off the corrugated-iron sheets. At this the terrified baboo in charge of the telegraph instrument below sent the following laconic message to the Traffic Manager:

Lion fighting with station. Send urgent succour.Fortunately he was not victorious in his "fight with the station;" but he tried so hard to get in that he cut his feet badly on the iron sheeting, leaving large blood-stains on the roof.Another night, however, he succeeded in carrying off the native driver of the pumping-engine, and soon afterwards added several other victims to his list.

On one occasion an engine-driver arranged to sit up all night in a large iron water-tank in the hope of getting a shot at him, and had a loop-hole cut in the side of the tank from which to fire. But as so often happens, the hunter became the hunted; the lion turned up in the middle of the night, overthrew the tank and actually tried to drag the driver out through the narrow circular hole in the top through which he had squeezed in.

Fortunately the tank was just too deep for the brute to be able to reach the man at the bottom; but the latter was naturally half paralysed with fear and had to crouch so low down as to be unable to take anything like proper aim. He fired, however, and succeeded in frightening the lion away for the time being. It was in a vain attempt to destroy this pest that poor Ryall met his tragic and untimely end.