In the winter of 2013 - 2014, we reviewed Elsa Ferrante's

second Neopolitan novel, gave it one of our rare

*STARS.*

Here's a list of other recent novels that we feel

deserve similar acclaim --- but, alas, have been consigned

to book purgatory by the caciques of the book biz.

1914

A Novel

Jean Echenoz

Linda Coverdale, Translator

(The New Press)

Many of us have long been fascinated by WWI. It burst on the world so suddenly, so illogically ... and then stayed around, it seemed, forever. Few authors have captured the first weeks as poignantly as Echenoz. We watch five fresh lads from the lush fields of the Loire caught up in a new mechanical noisy death-machine that consumes all in its path. We watch these young innocents learning the secret of sleepless days and nights, learning to survive in clay turned viscous (capable of drowning one), trapped from moving forward (by the enemy) or moving backwards (by the gendarme). You learn quickly that you are in jail where the only escape is losing part of your body or part of your mind (and often even that is not acknowledged). You lose your hope too, but there is nothing that can be done for that --- at least in WWI.Several historians (Niall Ferguson, John Mueller) have commented on the fact that as we move into the latter part of the 20th Century and the early part of the 21st, fewer and fewer are being slaughtered in the name of god, or bravery, or love-of-country. Perhaps after so many centuries of narcissistic mayhem, perhaps we humans are finally catching on. That bombs, flame-throwers, pistols, machine-guns, cannon, and hydrogen bombs may not be the most sensible way to convince others that we have right on our side.

Go to the complete

review

Firefly

Janette Jenkins

(Europa Editions)

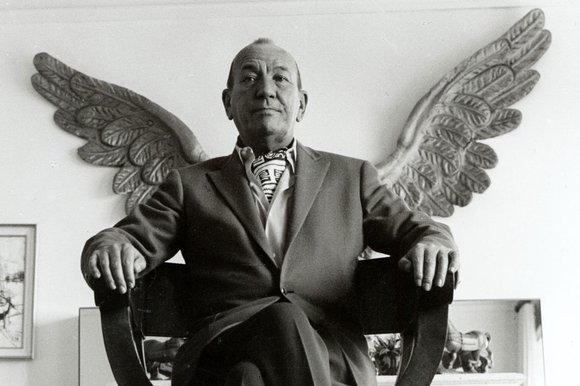

In retreat in Jamaica, Coward misses the fifties, a time when he could make goo-goo eyes at a young reporter from The Express. In Firefly it is presented as a mini-play:SMITH: And away from the theatre. Do you have a happy private life?

COWARD: Yes. I am really very fortunate in that respect.

SMITH [blushing]: Do you have someone special to share it with?

COWARD: I do indeed, but there's always room for one more. You have a very sweet face and I suppose you find me devastatingly attractive?

SMITH: Well, I...

COWARD: Don't be coy. We could slip into the bedroom. No one need know.

SMITH: [dropping his pencil]: I'm getting married, Mr. Coward. Next June.

There's a lot of stuff going on here that may strike one as being somewhat off-kilter. A reporter for a scandal sheet could, we should think, be the last that one should be accosting ... especially in 1950s England, where homosexuality was still a felony. (A year before this interview, John Gielgud got himself in a pickle, was convicted of "persistently importuning male persons for an immoral purpose [then called "cottaging"] in a Chelsea mews, having been arrested for trying to pick up a man in a public lavatory.")

In light of this, what Coward is doing comes across as foolhardy, but his instincts were right: he never got entrapped, nor had he ever been forced to pay blackmail (as far as we know) ... even though, at least according to Jenkins, he had a randy sexual life at a time when showing homosexual tendencies was considered to be a mental disease in the eyes of the bourgeoisie, and, as well, by the law-makers of America and England.

Despite this oppressive background, here is Coward, showing himself as being far from cowardly, playfully teaching a young reporter the lengths to which he will go to shock and dismay.

Jenkins could have put together a thick biography, and it would have been read, commented on ... and then dropped. She did something far more subtle: she wove the story of (what we used to call) an "aging queen," one who lived his outlaw life to the fullest, ever poking the hoi polloi in the ass, as it were, with his 'differentness.'

She has chosen the novel form with which to let us look into final days --- as his mind is beginning to go, his body already gone: a funny old galoot, moving heavily though his last days, needing help getting in and out of the pool, in and out of the tub, in and out of bed, "his nose white, his face red," his feet grossly swollen --- a man who made love to so many others, now gazing down sadly at his blasted "flaccidity."

It feels like a bereavement. An unnecessary loss.

But, like Mehitabel, there's life in the old gal yet.

Go to the complete

reviewEquilateral

A Novel

Ken Kalfus

(Bloomsbury)When Thayer and Bint are looking though his telescope at the red planet, he tells her,"Look well, Bint ... Look hard. Everything worth seeing lies at the edge of visibility."

He adds, "Every discovery lies within the standard error of measurement. The most important truths about the cosmos can hardly be separated from illusion."

And in our final look at Mars, Thayer spots something outside the disk of the planet, "a line, a red-pink fluorescing line, that he has never seen before. None of us have." Here we have a rare use of the first person plural, as rare as the color trail above the surface of Mars, "the unavoidable impression of the smoky effluvia that typically accompanies the discharge of a terrestrial cannon." This silent discharge results in "a single luminosity off the planet's surface," perhaps, one might think --- or at least Thayer does --- a sign of something that may be coming our way.

It is rare for this critic to become so involved with what we used to call "a tall story" like this one; it's even rarer to get sucked into the flower of mystery that only begins to blossom on the final pages. Our Bint is giving birth, no? But is it possible that something else is being delivered at the same moment? Why did Thayer just call for the building of "a customs house" next to the triangle? And what is that noise? "A foreign howl, a prolonged wail, slices through the sickroom. It reverberates against the walls and shivers the windows."

No one speaks as they wait for the next signal, the inevitable call of life; intelligent, companionable, needful, rampant life.

Go to the complete

review'Til the Well Runs Dry

A Novel

Lauren Francis-Sharma

(Henry Holt)

This is just your regular off-the-street Trinidad taxi driver talking to our love-lorn cop: "Your eyes must be burnin'! You payin' this kinda money to go way into de bush for some gal? You mad? I not gon' more than t'ree miles to find nobody! You're a good-lookin' fella, too. What you does need a country gal livin' behin' God back to rub against for? You can't get no nice Indian girl in Tunapuna to make some anchar and some dhal puri for you? You spendin' up your money on some red country, bookie gal?"He pushed the money I had paid him up front into his shirt pocket. "If I can't pass on de road, I keepin' de money and turnin' right around, you hear? I not goin' up to Blanchisseuse to dead in no pool of mud. Dem hills lookin' to bury me. I'll drop you right back here in Arima, but I keepin' de money. We a'right with that?"

That must have been what did it, what put a hex on us, made us fall in love with Farouk and Marcia and the whole of the 'Til the Well Runs Dry cohort. A scolding speech from an off-the-wall taxista, telling Farouk that he is definitely on the wrong road.

We know better. Because we've already met Marcia, and we're smitten with her. Taxi-man is right, the hills might bury us, but it's not Marcia's fault, because she's the one we'd like to run off with too, if we were just back there in our salad years.

She's feisty and funny, comes off like a Trinidadian Moll Flanders or calaloo Molly Bloom --- filled with spikes and smarts and all kinds of survival mechanisms for her and the four kids that Farouk manages to plant on her.

Go to the complete

reviewThis Life

Karel Schoeman

Else Silke, Translator

(Archipelago)

Why is This Life so captivating? My suspicion is that the only one who knows the answer would be Karel Schoeman. Her job is to write it and send out to the world (and with the help of a good translator) give us a mesmerizing book.When we finally get to the time that Sussie is about to take her leave of the world, as old and as decrepit as she is --- she somehow manages to make a trek (Africaan history is built on long, impossible treks) to the place where she had last seen her one beloved brother, Pieter, with his (and her) own beloved Sofie.

When she slowly, oh so slowly, makes the long trek home, barely surviving the cold and the wind . . . when she arrives, she gets to her room, and falls "into the blackness." The maid discovers her, a neighbor comes to help put her to bed . . . there in the very bed she was born in, the same room she had had when she was young.

There is no daybreak any more, only the dark; first darkness, then sleep. The dark has obliterated the moonlight, the dark has snuffed out the candle-flame; Pieter falls wordlessly from the window-sill, back into the darkness whence he had come, and only Sofie's black dress still glistens for a moment as she dances alone to the rhythm of the soundless music until she too disappears, a shadow in the shadows. They have found peace, and now this life can end too, the report delivered, the account given and the balance determined. The water had dried up and the soil did not retain the footprint. The darkness obscures it all.

Go to the complete

reviewMiruna

A Tale

Bogdan Suceavă

Alistair Ian Blyth

Translator

(Twisted Spoon Press) Enchantments. Spells. Otherworldly creatures. Charms. If you were raised like I was, we were deluged in this stuff when we were kids, either from "children's" books, or from Disney. If you're like me, and if you go back to the tales they told us, the stories that we heard, read, or saw we find now to be pretty tame stuff; the language (or the pictures) purposely toned down, "suitable for children" --- leaden, tired.

Enchantments. Spells. Otherworldly creatures. Charms. If you were raised like I was, we were deluged in this stuff when we were kids, either from "children's" books, or from Disney. If you're like me, and if you go back to the tales they told us, the stories that we heard, read, or saw we find now to be pretty tame stuff; the language (or the pictures) purposely toned down, "suitable for children" --- leaden, tired.Bogdan Suceavă (and his translator) have given us something else here. It is not only a tale of magic, but it is also comes with a magic language; one that, I claim, is very rare. "They were creatures of sap, love, and vapor . . . " "Come with me into the land of pine needles, and we shall live there in endless love." "In his song there was nothing but shadows, smoke, and love." The words, the very sentences themselves grow with and through necromancy.

And these gems pop up all over the place. One of the characters of the village of Evil Vale has a dog. "Berca later brought home a puppy, which grew to the size of a bullock, with a pelt like sheepskin, head as big as a bushel, from which a rough blueish tongue ever lolled." We've all seen dogs like that, but have they even been defined so wonderfully, and with such precision?

You think you have problems getting around, but try to come back as an angel, "with wings of dazzling white that were able to slice through the heavens in flight but a hinderance when he walked on the earth." All the anciens in Evil Vale live to be 100, 200 years old. Why? It's merely a matter of

dispensations from the laws of nature that allow time to be swathed like a shawl around certain people, a disturbance that is called deathless life, about which there is an old fairy tale where the most interesting character is not the scorpion or the woodpecker but Time itself.

I leave off giving you a run-down on the plot. With language like this, who needs a scenario? With language like this, who needs history --- for instance, the history of man learning to fly? "This happened the week Ioan the kite-maker, a man whose lifelong wish was that he'd been born a bird, discovered the secret of becoming airborne and managed to lift himself aloft from the Knoll using a mechanism made entirely of wood, with parts fitted together without nails and glued with a light resin."

Go to the complete

reviewThe Secret Keeper

Kate Morton

(Brilliance Audio)I had not heard of novelist Kate Morton before she appeared in my mailbox in the form of these seventeen discs from Brilliance Audio. But as I listened to the reading by Caroline Lee, I found myself more and more mesmerized ... by her and her tale unravelling rather brilliantly. There came a time --- as it should in all good readings --- when you do not want it to stop. Furthermore, to prepare this review, I borrowed the book, read through key parts. It got me to mulling on the difference between the written word and the spoken.For one thing, the rhythm and flow of the reading are perfect, and perfectly paced. Ms. Lee has quite a talent for that, has a hamper-full of all the right accents. Especially the accents of class which are so important in The Secret Keeper, and, as always, in that Tight Little Island we call Great Britain.

Class is as much at the core of this story as is the Blitz. Dorothy (and her love Jimmy) are out of the lower class, trying to rise above their station. Their foil, the astringent Vivien, is upper class, wants everyone --- especially Dolly --- to know it; seems at one point hell-bent on keeping her in her place.

This class act is important, and as Ms. Lee plays it, she shows, as she speaks, how important the accents are for the plot. Lee can turn old and petulant when she is speaking as noisy Lady Gwendolyn, or for the quiet and aged Dorothy. She turns young and anxious as she speaks for Dorothy, turns elegant as the untouchable Vivian. Finally, Laurel, old and famous, speaks beautifully, as if to the manor born.

§ § § If I could do it all over again (I wish I could!) I would seek out the spoken version of this novel. If you do, you may, like me, find yourself bewitched, unable to tear yourself away from it, letting yourself be perfectly transported into another world and another time, transported on the wings of the oldest of magics: the spoken word. There you'll find yourself, I believe, entranced by your own place in such a class act ... where people would rather die than let the world know where they think they came from, and where they think they're going.

Go to the complete

reviewA Long Way from Verona

Jane Gardam

(Europa Editions)If you need something to hang onto in A Long Way from Verona, there are asides that you're bound to cherish. This is dad preparing to prepare an article, "He tidies his desk, brushes the fireside, winds the clock, shakes the clock, opens the back of the clock and takes all its insides out. Then he throws all the bits away. The he gathers them all up again and stands looking at them for half an hour. Then he arranges them in rows, scratches his head, picks his teeth, sits down and takes his shoes off and smells them."And this: Jessica finds the part of the local library that has the "Classics," all 200 of them. She decides she is going to read them all, starting with the A's:

I don't know if you've noticed but if you want to become one of the English Classics it's a good idea to be up in the top half of the alphabet. There are a tremendous lot of As and Bs and Ds and --- down to about H. Then there's hardly anything at all, until you get to all the Richardson, Scott, Thackeray lot. It's rather depressing really and you don't feel you're making much progress when after a month you're just past the Brontës --- and when you see how many Dickenses are coming.

Best of all, Gardam lets herself tease the reader: "And now I will speed the story up and describe only the two main episodes of this time. Both are depressing and could be skipped if you are pressed." She's lying --- again --- but it is a Jessica-style lie: she doesn't mean to offend, nor to lie (outright), because that's only an adult interpretation. Like the poem she wrote in a trice and reluctantly let one of her teachers send off.

Of course it gets a first prize, wins her £20 --- which she immediately gives away --- and gets published full on in the Times.

Gardam teases us once more because we never get to see the poem ... but after spending all this time entranced as we are with Jessica Vye, we have no need to. Because we know it's good.

Just as she is.

Or like anyone twelve-going-on-thirteen on the cusp of raging hormones can be good, or something close --- very close --- to it.

Go to the complete

reviewHeading Out

To Wonderful

Robert Goolrick

Norman Dietz, Reader

(HighBridge Audio)Heading Out to Wonderful is told á là Lake Woebegone. These people are post-WWII American honorable moderne: clean, honest (except that rascally Boaty); faithful (five churches); true to their prejudices --- blacks kept over there --- but, somehow, honorable all the same. Charlie is saintly, his one flaw introduced discreetly. That is, he came to town with a suitcase full of money, and we don't have occasion to ask why, and Goolrick ain't telling. We can only guess, for Charlie's ability to wield the German cutting knives is uncanny (the way he butchers cows, the way he cuts the meat --- it always tastes better). Thus his last two acts of butchery come to become a given.

The story is nicely unfolded for us; we come to care for most of these characters. We are told early on that there is going to be trouble (the kid Sam doesn't reveal what he knows "until it was too late"). But there is a certain harshness here, perhaps, a brittleness. Of course, with Charlie's first glance at Sylvan we know there's got to be a fracas, and these people are not all that angelic, even for the late 1940s American gothic countryside. After all, Charlie cuts up cows for a living, sleeps with another man's wife. I suspect the harshness grows out of one man buying another man's daughter to be his wife: for $3,000 "cash money" and a tractor.

I heard this first in the HighBridge audio version. I can't tell you --- wait, I am telling you --- how entrancing the reading by Norman Dietz. It's one of the best narratives I've ever run across. Dietz's voice is perfect, and perfectly engrossing. Immediately after listening to it, I got hold of the book so I could write this review, get the quotes right, and, incidentally, reread the story. What a let-down.

Was it that I knew the plot now, knew how it was going to end, all the twists and turns? Is there that much difference between voice and print? Is it possible that this is one of those rare books, like one of those from the era of Richardson, Dickens and Balzac, that was solely meant to be read aloud?

Is it that Dietz is a mesmerizer, with his mid-America accent, his unflappable recounting, his calm and reason (it is, after all, a story of calm and reason, America small town life in 1948). It is and stays stolid until the accusation, the violence, the murders.

Whatever it is, I urge you to forego the pleasures of the page and seek out these eight CDs from HighBridge. I suspect you will be trapped, as I was, by the story never being hurried along: us (and it) always waiting for the next subtle, gentle, expressive move of events, to unfold for us ... moved by the voice, never by the eye.

Go to the complete

review

Hawthorn & Child

Keith Ridgway

(New Directions)Hawthorn & Child is divided up into eight chapters. Or sets. Or situations. Or mise en scènes. Wait, no: that's the movies. But the novel is filmic: scenes drift into each other, sometimes quite randomly. Some sections are cogent, fit. One entitled "Goo Book" was good enough to appear on its own as a story in The New Yorker. The chapter is a chiller, someone getting in over his head. Small-time crook gets involved with the dangerous Mr. Big, the one who can get you anything you need. The kid is chauffeur for him, gets more and more involved.How, I wonder, can a writer get us to worry about a small-time thug, wanting to be sure that he gets out from under? Is it because of the touches, that he lives with a woman and instead of communicating like the rest of us (words, looks, smile) they leave notes for each other in a notebook on the top shelf, never talk about what they write to each other, or themselves?

Some of the chapters here are complete stories, neat; others seem to be fantasies of nut cases who happen to come under the scrutiny of Hawthorn and Child. Most start out with a bang --- man trapped under car, car falling from jack; is he going to just die there, alone in a deserted garage?

Others are yarns that might be coming at us from Ixneria. One story called "Rothko Eggs" features Cath ... a twenty-year-old who is crazy about modern art. She's daughter of Hawthorn and Child's boss, Mark Rivers. We get to see the two detectives through his eyes, and it becomes a cautionary tale for all of us ... in case we are getting too fond of them, what with their funny dialogue and weeping fits.

Rivers tells her, "They are not nice. Really. And anyway, one of them is married and the other is gay and they're both old enough to be your father. And if your mother and I agree on anything, then we agree that you should never, ever, ever, get involved with a policeman."

Go to the complete

reviewThe Roy Stories

Barry Gifford

(Seven Stories Press)We have a link in it all, the necessary innocent anchor: Salinger's Esmé, Sherwood Anderson's George Willard, Bellow's Augie March. Here it's Roy, who comes across as your typical normal straight-arrow, a somewhat shy but often assured youngster of 1955, 1957 or 1962, living in Chicago with his mother, never really knowing his father, putting up with her continuous parade, most of whom drive him nuts (before they end up doing the same to her).For instance, there's Sid "Spanky" Wade, a jazz drummer (he "spanks" the drums) who damn near drowns in the bathtub. "He had been smoking marijuana, fallen asleep and gone under. Roy's mother heard him splashing and coughing, went into the bathroom and tried to pull Spanky out of the tub, but he was too heavy for her to lift by herself." She calls Roy, and

Roy and his mother managed to drag Spanky over the side and onto the floor, where he lay puking and gagging. Roy saw the remains of the reefer floating in the tub. Spanky was short and stout. Lying there on the bathroom floor, to Roy he resembled a big red hog, the kind of animal Louie Pinna had shoved into an industrial sausage maker.

"Roy began to laugh. He tried to stop but he could not. His mother shouted at him. Roy looked at her. She kept shouting. Suddenly, he could no longer hear or see anything."

And that's how "Bad Things Wrong" ends, like so many of these --- they just up and end like that, as if Gifford had gotten lost or something, or just quit typing, no matter how interesting the story is getting to be. So then we find ourselves out of one and plop! into the next.

One never worries, though. These are like eating Fritos or Oreos or Doritos, or better, a great hot dog on the streets of Chicago, with just the right condiments. And it's impossible to stop. Stories like "The Vanished Gardens of Córdoba" just --- bang --- begin in the middle, then go away; and then we move on ... and it's O.K..

Some are jewels, though. Forget the title of "Close Encounters of the Right Kind" --- wrong decade --- which is about Fatima Bodanski, who had the reputation of being a "fast girl," and Roy falls in love with in an instant. Or try "Blue People," about the Tuaregs and their dyed clothing. Or Roy visiting his old friend Eddie Derwood, committed to Illiniwek Psychiatric Institute. When he comes into the room, Eddie doesn't seem to see him. "His eyes were foggy and the corners of his mouth had white crust on them."

"It's me, Roy. Don't you recognize me?"

Eddie stared at Roy for thirty seconds before saying, "You're just a bird, a big, dark bird without wings."

Roy asks the attendant if he is on drugs. "You don't know that" say the attendant. The attendant says to Eddie, "You need somethin', Mr. Derwood. "Caw! Caw!" said Eddie. "Visit's over," said the attendant.

Go to the complete

reviewThe Mermaid of Brooklyn

A Novel

Amy Shearn

(Touchstone)Shearn is writing about a very exasperating situation. These kids. This tiny, hot, apartment. Detritus everywhere. And at times but only at times thinking that maybe what she is doing is worth it. "My everyday struggles held within them an echo of the legendary, that maybe if mothers had time to write, all the old epic poems would be about trips to the grocery store instead of wars."Her friend Laura --- another playground buddy --- seems to have a perfect (and easy) time at being mother to her daughter Emma. "Maybe not I would ask Laura how she get Emma to be so infuriatingly well behaved all the time --- special vitamins? secret beatings? --- in a tone that would attempt lightness only to stumble clumsily toward accusation."

Or: Jenny's memories of her previous job, when she edited, did rewrites, at a classy magazine, all this before she got cast as what-they-call a "stay-at-home-mother" ---

Working had been a fairyland of free lunches, unsticky surfaces, magical creatures who never required diaper changes and cried only occasionally and then quietly in the bathroom, trying to hide it.

And then there is the matter of missing husband, the one that one should just be deleted from her mind ... but she is not a computer, we just can't blot out someone who took up the major part of our lives for a few years and then disappeared: "I missed Harry. I missed Harry so much, so deeply, curled up there in what was once our bed, with Rose sucking at my breast, my breast that once was more than just food, with Betty curled at my back, her sleeping fingers coiling into my hair, my hair that Harry had always said he loved, no matter how unruly it got."

I missed my husband so much I thought I would die of it. My chest went hollow, and as Rose began to doze off, I saw in the dim light a few of my tears dampening her brow.

§ § § Shearn has a fine touch, managing in one book a scatter-shot recognition of things that have gone through my own life, the lives, I suspect, of many of us. She handles them gently and leaves us a little better, a little clearer for it. Stuff like Loyalty and Disloyalty and Hate-baby and Love-baby, Urban Community, City (esp. New York, esp Brooklyn) and Madness. Suicide, along with (perhaps part of) Boredom, Routine, and Maternity.

Then there are Morals (what are morals for, anyway?), Hiding feelings, Friendship, Our parents (how in the hell did they do it?)

Too, Spirit. Youth. Rebirth. And Enchantment, especially Enchantment.

Shearn is an enchanting writer. She doesn't miss a beat. All comes together as it should in The Mermaid of Brooklyn. She deserves your love, attention, and affection.

Go to the complete

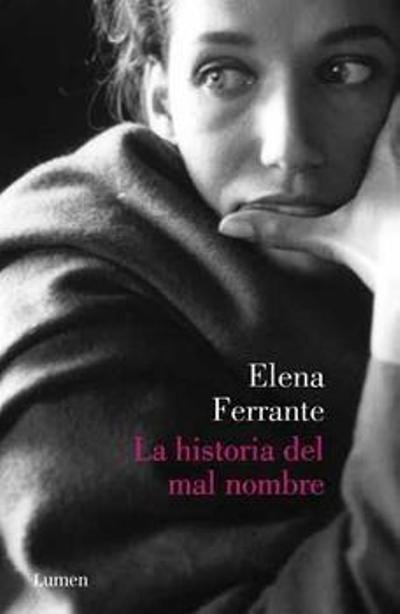

reviewThe Story of a New Name

The Neapolitan Novels: Book Two

Elena Ferrante

Ann Goldstein, Translator

(Europa Editions) On the first few pages of The Story of a New Name, like a Tolstoi novel, or a Shakespearian play, all the characters are listed --- although not in order of appearance. Don't be put off by the fact that there are over fifty names here, and ignore the somewhat inept notes about them. Melina Cappuccio ("washes the stairs of apartment buildings,") Nino Sarratore ("He hates his father. He is a brilliant student,") Enzo Scanno ("shows an unsuspected ability in mathematics.")

On the first few pages of The Story of a New Name, like a Tolstoi novel, or a Shakespearian play, all the characters are listed --- although not in order of appearance. Don't be put off by the fact that there are over fifty names here, and ignore the somewhat inept notes about them. Melina Cappuccio ("washes the stairs of apartment buildings,") Nino Sarratore ("He hates his father. He is a brilliant student,") Enzo Scanno ("shows an unsuspected ability in mathematics.")You'll mostly be concerned with Elena Greco who narrates the whole, and her childhood friend Lila Cerullo. They are the center of the action, and you'll be meeting many, maybe too many characters in their families. Like Elena's mother (unnamed), a genuine nag; or Lila's mother Nunzia, a sweetie (a good cook too).

Then there's Stefano Carracci who marries Lila and proceeds, in good Neopolitan fashion, to blacken her eyes when she doesn't do what he wants (which is most of the time). She doesn't budge. There are Lila's various extracurricular boyfriends and lovers: Antonio, Nino, Enzo, and about ten or fifteen others, cousins or no, who want to bed her, along with Pietro, Bruno and Donato, all of whom are smitten by Lila rather than simple plain-Jane loyal Elena. I figure if I lay out the plot for you, you'll end up being as confused as I am, what with the endless love affairs, plots, lies, insults, conjoinings, disjoinings, schemes and rages that will float away for you as they did for me. Quickly.

Despite this evanescence, I think you might get swept up by The Story of a New Name, perhaps somewhere around page fifty ... knowing that it's something you can lay down and pick up and get immersed in no matter what's going on in your life: life, death, joy, terror; one of those interminable times when you are waiting to get on or off an airplane, a train, a bus, or a passion-bust.

Don't be dismayed: it will take you a week or two to plow through the whole steamy entangled sweat-love life there in Naples ... knee-deep in the muck and bickering and inter-familial rivalries along with flirtations and murderous impulses that probably lie bubbling about in all of us, Neopolitan or no.

Because author Ferrante knows how to pile it on; and you too may find yourself falling for Lila ... or, better, Elena, the author's namesake who like any sixteen-year-old can change her mind in a trice, suddenly hate those she loves, then turn around and love those she hates ... even give away her own passionate heart-throb Nino Sarratore, offered up as a present to friend Lila.

Go to the complete

review