Six Weeks in World War I that Forever

Changed the Nature of Warfare

Diana Preston

(Bloomsbury)

Mankind has been unmatched when it comes to new inventions for mauling other men. But in May of 1899, in a fit of humanity in the waning years of the Victorian era, the major world powers got together at the Hague to declare that hereinafter, all wars were to be more humane.

Mankind has been unmatched when it comes to new inventions for mauling other men. But in May of 1899, in a fit of humanity in the waning years of the Victorian era, the major world powers got together at the Hague to declare that hereinafter, all wars were to be more humane.Say who? More humane? A dipsomanical idea if there ever were one.

A British admiral, Jacky Fisher, fulminated about the idea of the "humanising" of conflict, stating that the best cure for war was complete preparedness:

If you rub it in both at home and abroad that you are ready for instant war . . . and intend to be first in and hit your enemy in the belly and kick him when he is down and boil your prisoners in oil (if you take any) and torture his women and children, then people will keep clear of you.

Despite these sour grapes, the participants agreed to several dicta, including to promises not to use "poison or poisoned weapons," arms or weapons that caused "unnecessary suffering," as well as forbidding

the attack or bombardment, by whatever means, of towns, villages, dwellings or building which are undefended, the pillage of a town or place even when taken by assault."

To show his inherent faith in the agreements agreed to by the end of the conference, Kaiser Wilhelm II signed them and wrote in the margin,

I consented to all this nonsense only in order that the Tsar should not lose face before Europe, in practice however I shall rely on God and my sharp sword! And I shit on all their decisions.

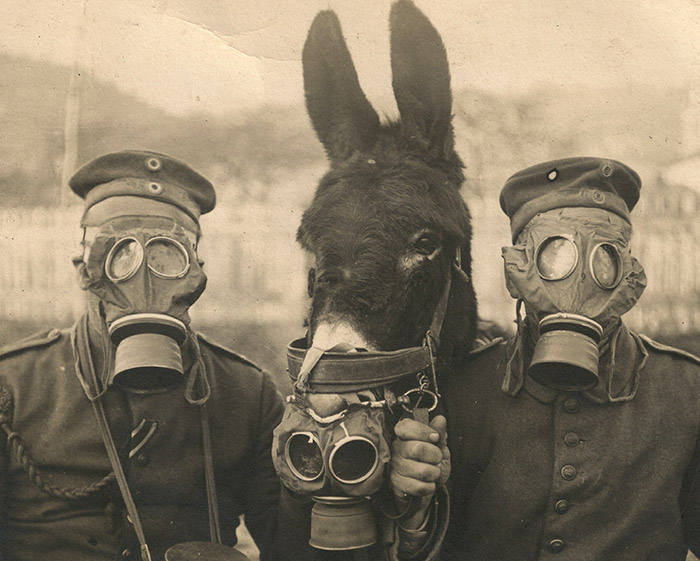

Which set the scene for Germany to patently ignore these dicta in 1915, during the spring and summer months of World War One. Gas was released by Germans on the morning of April 22, 1915 against Canadian troops at the Ypres Salient: it could be seen as "puffs of white smoke rising from the German trenches." According to a German airman flying over,

how extraordinary it looked when the clouds came up to the enemy trenches, then rose, and after as if it were peering curiously for a moment over the edge of the trenches, sank down into them like some living thing.

The result? "Men who had fled their positions were everywhere . . . haggard, greatcoats thrown away or hanging open . . . running hither and thither like madmen, crying loudly for water, spitting blood, some even rolling on the ground in a desperate struggle to breathe." One observer said,

It produces a flooding of the lungs . . . the coughing up of a greenish froth off the stomach and lungs, ending finally in insensibility and death. The colour of the skin turns a greenish-black and yellow, the tongue protrudes and the eyes assume a glassy stare.

Chlorine, phosgene, diphosgene, and mustard gas. During the course of the war, it is estimated that it caused some 1,300,000 casualties. And a vicious horror. As one combatant wrote, with unintended irony: "Clean killing is at least comprehensible, but this murder by slow agony absolutely knocks me." It did "knock him" in the end by killing him.

What were the two other "higher forms of killing" that make their appearance here? The first was the bombing of cities in England by the German graf zeppelin, starting in 31 May 1915, and then on and off for the rest of the war. The second: the German resumption of "unlimited submarine warfare" --- the sinking of ships even when there were innocent citizens aboard. For the havoc it caused, the most telling of them all was the sinking of the Lusitania on 7 May 1915.Before she sailed from New York, the New York Times carried an announcement released by the Imperial German Embassy reminding travelers that "a state of war exists between Germany and her allies and Great Britain and her allies . . . vessels flying the flag of Great Britain, or any of her allies, are liable to destruction."

Forewarned, etc. If it had been me, I would have lost my ticket, or would have called in sick on the day of departure. Most thought it an empty threat. The captain, William Turner, said that talk of torpedoing the ship "was the best joke I've heard in many days." Ho.

He was helped along by Cunard's general manager, Charles Sumner who came down from Boston to the pier to tell would-be voyagers that "The fact is that the Lusitania . . . is too fast for any submarine. No German vessel or war can get near her." In other words, no sweat, don't worry, don't cash in your ticket. Thanks, Charlie.

As the ship departed, the ship's band plowed enthusiastically in to "It's a Long Way to Tipperary:"

It's a long way to Tipperary,

It's a long way to go,

It's a long way to Tipperary,

To the sweetest girl I know!

Goodbye Piccadilly! Farewell Leicester Square!

It's a long, long way to Tipperary,

But my heart's right there!(Other songs dedicated to this drab, wet, and remote village include Gary Moore's song "Business as Usual" which goes: "I lost my virginity to a Tipperary woman" and "Forty Shades of Green," written by Johnny Cash. Forty. Not fifty.)

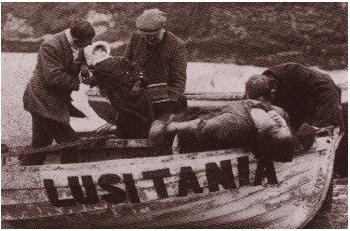

The town did prove to be a long way for most of the passengers. The German submarine U-20 found her off the coast of Ireland and sent off a three thousand pound torpedo which caught the ship "starboardside right behind the bridge." The Lusitania sank eighteen minutes later. One passenger subsequently told of "the bodies of infants laid in life jackets floating round with their dead innocent faces looking towards the sky."

By May 12, the world knew that the Germans were responsible through their coded cables, intercepted by the British, including one sent from naval high command headquarters in Germany to the U-20:

My highest appreciation of commander and crew for success achieved of which the high seas fleet is proud and my congratulations on their return.

The German press "applauded the attack as an 'extraordinary success.'" Of the 1,959 passengers and crew, 1,198 died of injury, drowning or exposure, including 49 children. As the Ms. Preston notes dryly, Compared with daily casualty figures at the Front, the Lusitania fatalities were tiny. But world reaction to what had occurred off the Irish coast was enormous. It is highly likely that the Germans lost the war on that day in May 1915. Americans, not moved by the toll of young men's lives on the fronts at Ypres and Passchendaele were struck by the image of the forty-nine children floating like flowers on the cold Irish Sea.

The final "higher type of killing" offered by the author is the bombing of southern England by Zeppelin which began in the summer of 1915. The kaiser personally approved the airstrikes with the provision that "no historic buildings should be targeted." However, since much of the London area was fogbound, these raids turned out to be catch-as-catch-can. The L12 dropped "ten enormous bombs" on Dover. One English observer was smitten by the beauty of it, and he wrote, "It was a most wonderful sight, the searchlights on the hills round picked her up very quickly and concentrated on her and she looked exactly as if the sun was shining on her --- and she was only about 4,500 feet up and looked enormous."

About a later raid on London, the American newspaperman William G. Shepherd wrote,

Here is the climax to the 20th century. Among the autumn stars floats a long, gaunt Zeppelin. It is a dull yellow --- the colour of the harvest moon. The long fingers of searchlights reaching up from the roofs of the city are touching all sides of the death messenger with their white tips.

He concludes, artistically and with insight, "Suddenly you realize that the biggest city in the world has become the night battlefield on which seven million harmless men, women and children live. Here is war at the very heart of civilization, threatening all the millions of things that human hearts and human minds have created in past centuries." Welcome to the 20th century.

But the kaiser called off these attacks in late 1917. Why? For humanitarian reasons? No: because new zeppelins "broke up in strong winds" at the heights needed to avoid being shot down.

In all, the lighter-than-air ships attacked London and environs twenty-six times, "killing nearly two hundred Londoners, injuring more than five hundred, and causing one million pounds of damage." In comparison to other forms of slaughter, the zeppelins were, presumably, not cost-effective.

We have reviewed one of Ms. Preston's books before. In a 2002 volume titled Lusitania, we found the narrative to be somewhat rambling. The book wandered hither-and-yon on the Seven Seas until the good vessel finally makes its appearance on page 92, and it peters out after it lay rusting on the floor of the Irish Sea.

This volume we found the writing to be more orderly. There are affecting quotes from the participants that emphasize novel and heart-stopping levels of international blood-letting. One German submariner told of the crowded nature of the U-boat, where sausages were "wedged next to grenades." He didn't bunk with the sausages, but with something a bit less plebeian, for "when the boat was fully loaded there was one torpedo more than there was place for. I accommodated it in my bunk. I slept beside it."

I had it lashed in place at the outside of the narrow bunk and it kept me from falling out of bed when the boat did some of its fancy rolling. At first I was kept awake a bit by the thought of having so much TNT in bed with me. Then I got used to it.

Even more disturbing are the words of a British sergeant major, Richhard Tobin, "who had fought through since 1914." He wrote,

The armistice came, the day we had dreamed of. The guns stopped, the fighting stopped. Four years of noise and bangs ended in silence. The killings had stopped. We were stunned.

"I should have been happy. I was sad. I thought of the slaughter, the hardships, the waste and the friends I had lost."