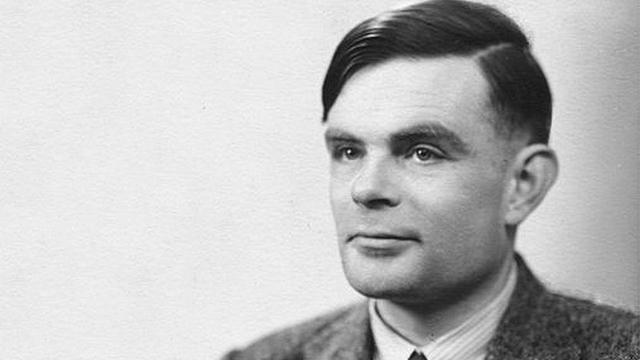

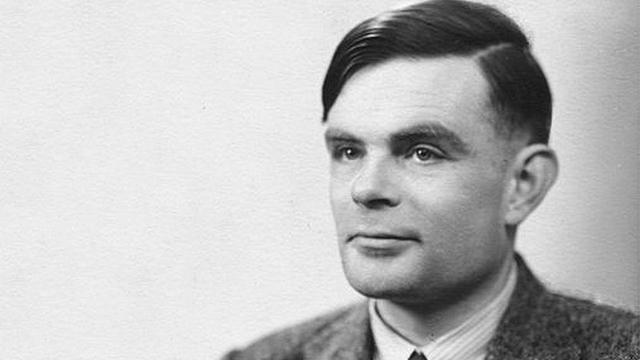

Turing

Pioneer of the Information Age

Jack Copeland

(Oxford University Press)

You already know the important computer stuff about Alan Turing, right? He essentially invented the beast back in 1936 when he was but twenty-four years old, publishing a paper on the automatic machine. And Turing's "a-machine," when finally built, was a beast, filling a huge room. For the next ten years, Turing made his computers sing, talk, play tic-tac-toe, and, most importantly for England and a world under threat from Nazi Germany, he created a computer during WWII that could decode messages that went between Nazi general headquarters and all German airplanes, troops, and submarines. The author of Turing thinks he alone may have been responsible for shortening World War II by two years, saving millions of lives.According to Copeland, Turing's biggest hit was the one we use today

to shop, manage our finances, type our memoirs, play our favorite music and videos, and send instant messages across the street or across the world. It was made possible by a single invention, as important as the wheel or the arch, called the stored-program universal computer.

"In less than four decades," he concludes, "Turing's ideas transported us from an era where computer was the term for a human clerk who did the sums in the back office of an insurance company or a science lab, into a world where many young people have never known life without the internet."

But let's forget Turing and the computers. The real interest here --- recently hetted up by the media --- has to do with Turing's death. The media claim is that he did himself in by suicide in 1954. This was primarily caused, the current myth has it, by Turing's being caught as a homosexual, then being forced to undergo a procedure called "chemical castration" as administered by the British government.

This story is that in mid-1952, Turing spent a few nights with Arnold Murray, a 19-year-old unemployed man. When Turing's house was burgled the day after a tryst, Turing decided that Murray was responsible, and hauled him over to the neighborhood police station. In front of the police, Turing said that Oh yes, he and Murry had had sex. Dumb move, especially in the England still in the toils of late Victorianism.Turing was immediately arrested and charged with "gross indecency" under Section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885. After his conviction, he was offered the chance to go to jail or to undergo hormonal treatment designed to kill his libido. He accepted the option of treatment via injections of stilboestrol, a synthetic estrogen. This treatment was continued for the course of one year.

The story now is that the public revelation of his sexuality (and his shame) caused his suicide in 1954. For instance, an article in the Guardian reported that Turing "took his own life 55 years ago after being sentenced to chemical castration for being gay."

In an official apology from the government, the Prime Minister, Gordon Brown, said that

In 1952 Turing was convicted of "gross indecency" --- in effect, tried for being gay. His sentence --- and he was faced with the miserable choice of this or prison --- was chemical castration by a series of injections of female hormones. He took his own life just two years later.

His suicide weapon was thought to be an apple laced with cyanide.

However, author Copeland offers up a brief but vigorous demurral to all this, presenting facts that do not point to depression, angst, shame and suicide. Those who knew him in his last two years say that he "enjoyed life so much." "One of Turing's friends reported that he went through the "chemical castration" with what was described as "amused fortitude."

In any event, after the twelve months, Turing was again seeking out young men (one described by him as "luscious"), and in the summer of 1953, he set out for holiday at the Club Méditerranée in Ipsos on Corfu. Copeland refers to this as "sun, beaches, men."

His career, moreover, was at one of its highest points, with his research ... going marvelously well and the prospect of fundamentally important new results just around the corner.

His mother Sara reported that "he was at the apex of his powers, with growing fame ... by any ordinary standards he had everything to live for."

If Turing was suffering from life-threatening depression following the months of hormone treatment, there is no evidence of it. His psychotherapist, Franz Greenbaum, wrote shortly after his death, "There is not the slightest doubt to me that Alan died by accident." Most neurotics tend to avoid all mention --- and being seen with --- their analysts. But instead of being ashamed of being in therapy, the author tells us that Turing had become great friends of Greenbaum's family, spending evenings and weekends with them.If his death was an accident, there are good reasons why it was possible for the scientist to inadvertently poison himself. Turing had been doing some improbable experiments in his home with cyanide crystals. A fruit jar that once had held cyanide was found near his bed (which is why the official report claimed suicide).

However, it is thought likely that Turing had eaten an apple that that had gotten mixed with the cyanide by chance. "Sara thought he must have taken in the cyanide accidentally," Copeland writes. He comments,

Turing was a klutz in the laboratory. Through sheer carelessness he got high-voltage shocks, and he sometimes assessed his chemical experiments by sticking his fingertips in and tasting. Tolerating a jar of cyanide crystals rolling about in his chest of drawers is just more of the same.

Don Bayley, who worked with him in a laboratory for more than a year said that Turing was quite capable of putting his apple down in a pool of cyanide without noticing what he was doing. The author concludes, "It should not be stated that Turing committed suicide, because we just don't know."

Turing's martyrdom fits neatly with our beliefs about the mandatory suffering of genius. It also fits with the facts: the first six decades of the 20th century were a time of ridicule of gays, complete with queer-baiting and legal entrapment. But as Copeland has drawn a compelling picture of a man who could be paradoxical ("He might ask if you can say why a face is reversed left-to-right in a mirror but not top to bottom") ... along with the portrait of a man who was "open and merry."

Turing was a man who believed in the truth --- his own, above all --- coupled with a persona that was simply fun to be around: "cheerful, lively, stimulating, comic, brimming with boyish enthusiasm."