Humanitarian Quests, Impossible Dreams

Of Médecins Sans Frontières

Renée C. Fox

(Johns Hopkins University Press)

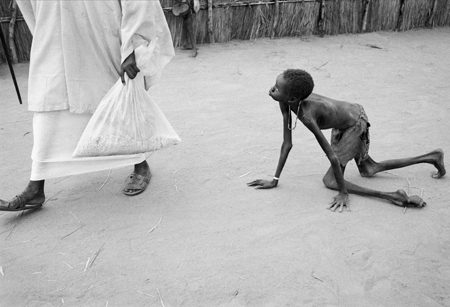

Médecins Sans Frontières began its work in 1971, organized by a few French doctors and journalists. Since then, it has bloomed to encompass 27,000 personnel, working in over sixty countries to provide medical assistance to people faced with "violence, neglect, or catastrophe, primarily due to armed conflict, epidemics, malnutrition, exclusions from health care, or natural disaster."Deployed in stable, unstable, armed conflict, and post-conflict contexts, MSF was carrying out ten million consultations annually --- vaccinating hundreds of thousands against meningitis or measles, performing 43,000 surgical operations, delivering 73,000 babies a year, and caring for patients suffering from malnutrition, mental health problems, the aftermath of rape and sexual violence, and increasingly from HIV/AIDS ... the number of staff in the field has more than doubled, from 11,253 to 24,666.

Renée C. Fox's book is an attempt to show the works of that august organization, and how it has survived despite problems from within and without. We all know about the praise given, deservingly, to the organization for its ability to fly quickly into a disaster areas, bringing medicines and medical and technological help. What we learn in this volume are of surprising areas of deep inner-organizational conflict over questions about those who presume to enter a foreign country to assist in medical and humanitarian needs.

Some inner rumblings in the MSF have threatened, at times, its very existence. Such as a long-term controversy over medical help vs. political witness. When MSF goes into a country suffused in civil conflict --- Darfur, Sudan, and the Kivu region of the Congo --- should it stay away from any controversy? Or should the organization use this chance to point to the world the roots of physical harm devastating the citizens of that country.

In January of 2001, Kenny Gluck, working as the head of MSF Holland's North Caucasus project in Russia, was abducted from a humanitarian convoy in Chechnya. He subsequently wrote, "The attempt to stand by and assist the victims of violence brings us into confrontation with those who control violence ... The recognition that aid is inherently risky doesn't mean that everywhere it is dangerous, but it does mean that there is no means by which MSF can manage risk out of our programs."

It has been suggested that risk-taking is a collective matter:

Without it, we risk maintaining the demagogic and deceptive myth of the heroic humanitarian; of seeing the development, as in other organizations, of missionary tendencies accepting sacrificial mindsets far removed from humanitarian responsibilities; and finally, of cultivating a feeling of being all powerful.

Despite these caveats, one cannot but feel a thrill of delight when we read about the speech of James Orbinski, at the 1999 Nobel Peace Award ceremony in Stockholm. He, a founding member of MSF Canada, speaks on behalf of the entire organization, accepting the Peace Prize, then turns to "the Russian ambassador seated in the audience, [and] said:"

I appeal here today to his excellency the Ambassador of Russia and through him to President Yeltsin, to stop the bombing of defenseless citizens in Chechnya. If conflicts and wars are an affair of the state, violations of humanitarian law, war crimes and crimes against humanity apply to all of us --- as civil society, as citizens, and as human beings.

Some of the most hair-raising passages in Doctors Without Borders come at the very beginning, the "field blogs" posted online at http://blogs.msf.org/en. If you go there, you might want to run through some of the passages rather quickly, as details of horror and sickness and woe and physical plights may surely curl your short hairs.

Or you might want to merely check the blogs that Fox includes in the first chapter to this book. Such as,

The end of a mission means writing a report of what you did and what's left to do. But it's also a time when I do my own self-assessment, and ... I find I've gained skills outside my job description. I can catch mice with an old-fashioned mouse trap (use peanuts); I'll use the radio alphabet when spelling my last name on the phone ...; the key to lighting a gas heater is to strike the match BEFORE turning on the gas; I can read Russian!

Or,

Today, I'm thinking about a generous gift of avocados from a woman who probably didn't have food to spare. I'm thinking about the color of a stillborn baby's perfect feet and the shadow in the empty crook of her mother's arms ... I'm thinking about the pleasure of being chosen by a child. Taking the offered hand, returning the smile. And realizing suddenly that the tuberculosis medication is working and this little boy is miraculously, wonderfully, being restored to health and mischief.

Or,

I have been home for five weeks ... I have spent a lot of time staring at my bedroom ceiling. A good friend told me that it's probably normal and to keep doing it as long as I feel like it, and that eventually I will want to get up and paint the ceiling ... that hasn't happened yet.

There are a few cruel surprises here. We would think that a wretched country with a disheveled economy, befouled by war, plagues, disasters, or other nasty tricks of fate would welcome any help whatsoever when doctors and nurses and equipment and medicine come for free. For example, as we all know, the sub-Saharan areas of the African continent are awash in an HIV/AIDS pandemic. We are told,

The eight counties of the world most affected by AIDS are in southern Africa. Botswana comes first. If the risk of HIV transmission doesn't change, 85% of all boys of Botswana aged 15 today will sooner or later die of AIDS. In the year 2020, normally there would be 180,000 inhabitants in Botswana aged 35 to 40 years ... But because of AIDS, there will only be 60,000. Two-thirds of this age group, future farmers, merchants, doctors, nurses, teachers, but most of all parents, will have died. They will have died too young to have raised their children as independent adults, too young to have passed on their knowledge of how to work the land, or their modest businesses, too young to contribute their knowledge and experience fully to their community, too soon to help a next generation to accomplish higher studies. A decapitated society.

In South Africa, the government of Thabo Mbeki opted to obstruct plans by the MSF to initiate antiretroviral therapy. This included "playing down the gravity and extensiveness of the incidence of AIDS in South Africa,"

The incumbent Minister of Health, Tshabalala-Msimang, theorized that the best cure for AIDS was "garlic, beetroot, and lemon juice," and he actively supported one Matthias Rath, a German physician, who sold high Vitamin-C pills "that resembled the antiretroviral drugs."

- challenging the role that heterosexual relations might have in the transmission of the disease;

- claiming that antiretroviral therapy could have toxic effects;

- suggesting that those who were offering assistance in this pandemic were individuals who had supported the previous apartheid regime.

Finally, in the ultimate chapter, Fox tells of MSF's efforts to assist prisoners and the "street people" of Moscow. Once again, someone with common sense would think that a cohort of doctors, nurses, and technicians offering a treatment plan for prisoners suffering from a highly contagious antibiotic-resistant TB in the gulag would be immediately embraced. Coupled with an offer to help the people of the streets of Moscow, at no charge, would be welcomed with open arms.

No dice. What MSF didn't figure on was the cultural resistance of a country where the government viewed their own treatment plans as being superior to those offered by WHO with its regimen of western medical practice. Plus, there was the problem of sheer prejudice. The citizens of the Moscow saw the 30,000 homeless of Moscow --- known locally as the bomzhi --- as "vagabonds, beggars, drunkards, thieves, criminals, and disease-spreaders, 'good for nothings' who deserved their lot." Yet, in survey, MSF had found that "one in ten had a college education, one in five vocational training ... and that most were law-abiding citizens with no criminal record, were fit for work, were looking for a job."

The most common medical conditions from which they suffered were not infectious diseases, but trophic ulcers and infected wounds due to exposure to the elements, poor living conditions, and lack of access to medical care.

MSF was allowed only to begin its program for the bomzhi with a special operation for street-children ... but as time went on the bureaucracy of Moscow managed to strangle the international project. The publicity that MSF had generated was, unfortunately, somewhat sensational. The theme was "Indifference is Murder," but most Moscovites did not think of themselves as murderers. MSF was gradually squeezed out of the city, and finally denied access to the gulag.

Fox calls this book a "sociological" portrait of MSF, but it well may be more than that. It certainly is a warning for those who set out to Do Good In and For the world. In 1637, in the Religion of the Protestants, William Chillingworth wrote "I once knew a man out of courtesy help a lame dog over a stile, and he for requital bit his fingers." MSF not only has gotten its fingers bit, a few of their volunteers have been shot at, burned, kidnapped and --- in a few cases --- murdered for their troubles.

We cannot but admire those who venture forth to help those in need. As Kenny Gluck said, "we risk maintaining the demagogic and deceptive myth of the heroic humanitarian," but in Doctors Without Borders we have record of the honest attempt of the few to diminish human tragedy in the most humble way possible.