Under the Tripoli Sky

Kamal Ben Hameda

Adriana Hunter, Translator

(Peirene)

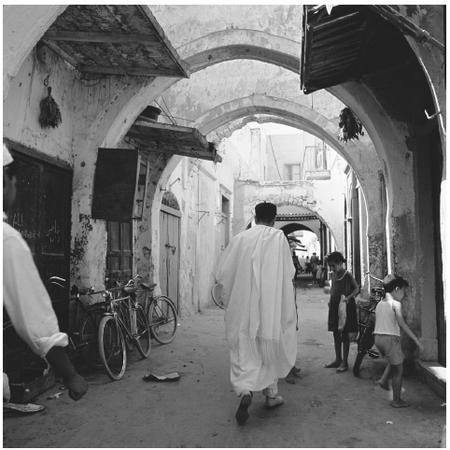

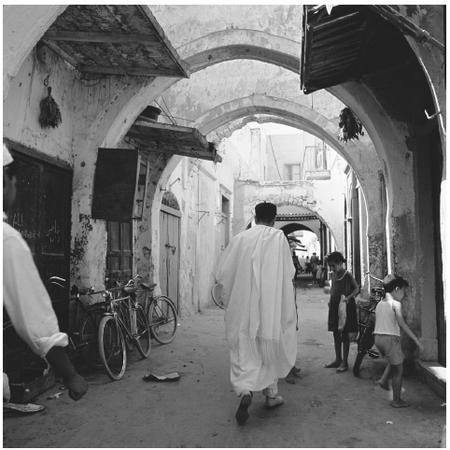

Hadachinou, a young Libyan boy, wanders the streets of Tripoli, visiting the graveyard to huddle next to the tombstone of the imarabouts, the holy men. He listens to the birds "and headed off to enjoy the company of the Mediterranean."Its presence gave me a sense of calm, as if underground rivers deep inside me stopped churning.

The wandering boy seems to have no friends except for the women. The only time men enter his world is when he tries to talk to his grandfather (his grandfather shakes his head; he talks only to Allah) or when his father brings the men to circumcise him.

The rest of the time he's alone or with Jamila or Aunt Nafissa or Fella "who could keep my secrets and who listened even when I told her the most outlandish stories: that I was half angel and half human, that I could fly if I wanted to but restrained myself so as not to attract attention. . ."

Perhaps at that age, the author suggests, boys are not unlike women. He says "I could listen to them talk for hours on end, all of them."

Even Touna, always so sad, I listened patiently to her moaning, her grumbling, her ranting, knowing not to mention the word, the root of all her pain, the taboo word that she couldn't bear to hear, the word "Father."

§ § § So he goes about in the city without companions --- visiting the fairs, watching people going in or out of the mosques, or in and out of the whorehouses, returning home to hear his mother's friends talking about their woes and their daily tasks and their men, saying over and over again that "they're being punished and that their punishment is men, yes the love of men."

Their stories are funny, garish, sometimes almost too graphic. Fella says that she seduced men "to have my revenge, to make them my slaves, to distract them from their lives until they were my loyal worshippers who could even forget their slave status. My body was the bait that they could never actually catch." She was at the synagogue and there was a man who would not leave off staring at her, so she goes home, leaves the door open for him. Then "I took him in my arms."

When he was asleep I undressed him and perfumed him with aromatic herbs. I burned incense and called on the god of darkness. I cut up his penis and ate it, grilled and seasoned with black pepper and cinnamon: because unlike pork, a man's flesh doesn't taste of anything.

"I helped more than one man in this way, spilling blood to return him to virginity . . . to become a eunuch. They always hid their shame; most have become mystic rabbis possessed by the Unnamed God."

Fella claims to be one of the Unnamed Gods, "the woman from the end of time that will soon come for all men. I am the chosen one of the world of darkness, of its secret lights and sacred babblings."

§ § § We can easily become enchanted when we are young. And for this boy, the enchantment flows from the women who understand, share and help fabricate his enchantment. There is Siddena: "Others might have become lovers. We became confidants, arranging to meet whenever the house was empty, to lie side by side again."

I was very surprised to hear that she had trees as ancestors but that her people were also nomads, that their black skin was the mark of the Chosen People of the Light, and they were threads leading from that light.

Despite taking place in the oft-violent Libya, we see no violence here except for the butchering of the sheep, Fella's rather dodgy, spicy meal, and --- with it --- the boy's own circumcision, performed with a razor by a barber, two men holding the boy down, during which he enters his own enchanted garden:

for the first time, I delve deep inside myself to find the place where I can safely watch episodes of my life, like someone sitting at a window and watching the never-ending entertainment of the street through the slats of the shutter.

"I can safely watch . . . like someone sitting at a window." Perhaps Hadachinou has become a sorcerer too.

He spends days looking in the mirror, then goes to lean against the headstones of the holy men in the graveyard. He is seduced (perhaps, perhaps not --- the writing is gently vague), there at the Freak Show, by one who calls herself Narcissus. She gives him a name too, "Ghostiman," and takes him into her room, lights a candle, takes him to bed, where

She the face-lady and I the mirror-body, we wandered through meandering subterranean galleries peopled with disembodied faces of men, women, boys, girls . . .

§ § § Ben Hameda's book could be seen as a misandrist's bible; the final word --- or words --- from and for women who hate men. But our perspective is shaped by the vision of a solitary boy, so it seems somehow less cruel The women here have become enchantresses, and by turning spiritual, perhaps make Hadachinou more spiritual.

"I was born before time," says the sorceress Kimya, "born of a sugary flower the colour of silk."

My people live on the others side of the light. I am the goddess with no tablets of laws or commandments. My spirit is everywhere and nowhere: I am the invisible visible, the interior exterior, the absent presence, the sleeper awake, the beautiful and the ugly, the merciless and the compassionate.

"I am the goddess with no tablets of laws or commandments."

Under the Tripoli Sky is a captivating book, telling of spells, and city witches, and enchantment, and youth . . . and the price women pay for being women (and the price of their revenge).

The writing is perfervid, its spell enchanting. We are told that the author is a jazz musician who lives in Holland. I suggest that if you ever go there, that you go to hear him play. When the music is done, ask him if he will have a drink with you. Hope that he will enchant you with a fable or two.

--- Lolita Lark