Into the War

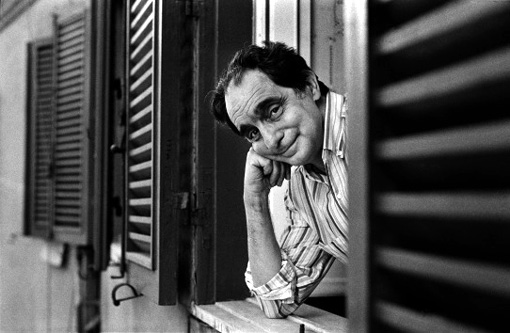

Italo Calvino

Martin McLaughlin, Translator

(Mariner Books)

Books like The Red Badge of Courage, and Frederic Manning's The Middle Parts of Fortune and Sagittarius Rising by C. Day Lewis along with War and Peace and some of the pieces that Hemingway and Orwell wrote during the Spanish Civil War bring us, the reader, onto the battlefield early on, not after people had shot or been shot at and hid in trenches or behind trees and gone nuts with the noise and confusion of it over the months, seeing blood and bone and earth.No, I am referring to the earlier moments, the wars that Tolstoi and Crane and Lewis gave us which told of the immense confusion that takes one over just as the battles start. You arrive green on the fields where there are still trees and birds and streams, wheat growing off there in the distance, the jays and nightingales and doves making their noises of late summer; the ease and gentle settling before the first cannonball tears into the ground, dissolves the field before you, dissolves whole peoples, making one wise long before one should want or need to be wise about the murk and madness that let us know immediately that we are participating in one of humanity's odder activities: that is, doing something so drastic that years later one side can to rise up with pride, lord it over the other side, let them know that they've just been had.

With this misapprehension of victory, honor and justice waiting, it is best not, I suspect, to be there at all.

§ § § It's a fine coincidence for this writer that in one week I've had the chance to go off to war with the British Expeditionary Forces, to learn from the soldiers' own notes and letters of the astonishing confusion that comes in the earliest battles in the earliest days: in this case, the early fall of 1914:

We saw a crowd of some two or three hundred Germans standing in the open in front of the cutting with their hands above their heads. Some of them had even got their shirts off, which there were waving as white flags. When I arrived about 150 yards form them I was rather at a loss as to what to do next. On field days at Aldershot we had never reached the stage of capturing prisoners wholesale. I remember turning around to my platoon sergeant and asking him what was the procedure for taking prisoners. He suggested that it might be as well if I drew my revolver. As I was entirely unarmed I thought this was good advice, but on doing so, the Germans nearest to me set up a wail and so I put it away again. I then advanced a little way and beckoned to them to come over to me. Finally one very dirty little man came timidly forward, and when about a yard away, made a dart forward and began shaking me warmly by the hand. This was embarrassing, but I do not quite know what made me give him a biscuit, which was my next action. This was too much for him altogether, and I believed he would have embraced me if I had not handed him over to two men to be searched. After this they came in quietly enough and were searched. As the officer next me had more prisoners than I had I handed over my lot to him together with my platoon to guard them.

With Calvino's Into the War, we have a chance to participate in another of the earliest skirmishes of another war --- WWII --- near San Remo in northwest Italy, between France and Italy. The author tells us, speaking of his own youth, "the evenings were lovely, the blackout seemed an exciting new fashion, the war seemed something distant and routine: in June we had felt it looming over us, but just for a few astonishing days; then it seemed to be completely over, after that we stopped waiting." Because of his age, Calvino sees his younger self engaged in a war of "derring do."

in which somehow I found myself happily free and different. So I experienced both the pessimist and excitement of those times, and I lived in confusion, and went out to amuse myself.

The war was young, he was young, and he remembers that summer, but not tanks and bombs, turmoil and bedlam, but merely longing to be friends with the young leaders of his fellow child-soldiers. "Perhaps that was exactly the time when I began to enjoy living, even though I was not aware of it, because I was at the age when you are convinced that every new thing you gain is something you always had."

There is not much of such gentle philosophy in "The Avanguardisti in Menton." Calvino is a realist (he wrote novels but was also an experienced journalist) --- so the writing is plain, the facts are quietly stated, and his adolescent havoc is woven into the havoc of two countries at war.

There is a lengthy description of the devastation of Menton not by bombers nor by shells or grenades or cannon but by the young fascists from the Ligurian area of northwest Italy who brought "vandalism inside houses: smashing everything, down to the last cup in the kitchen, into a thousand pieces, defacing family photographs, reducing beds to shreds, or --- overcome by God knows what depraved perversity --- shitting into plates and saucepans."

On hearing such tales, my mother said she could not believe such things could have been done by our people; and we were unable to draw any other moral except this: that for the conquering soldier every land is enemy territory, even his own.

Menton, it turns out, was not much of a victory for Italy. They took Menton over after France collapsed in the summer of 1940, but it was a minor triumph. "Our entry into the war . . . had not taken us to Nice, but only to that modest little border town of Menton." Germany reserved most of the spoils of the French Rivieria for itself.

There is little mention here of other battles from the early days of the war. For the young, wouldn't it be the same everywhere? During the bombing of London in 1940, young people in Yorkshire would still be out in the streets, hamming it up with each other, eyeing their buddies, trying out love, doing foolish fifteen- and seventeen- and nineteen-year-old things.

I remember, because it was almost the same for many of us later in the war, in February of 1945. The very day that Dresden was getting demolished, those of us in Sydney or Durban or Hong Kong or Manchester were wandering the streets, thinking of some mischief we could get into late at night before we went home to bed, something dumb that would make the girls pay attention to us (breaking street-lights, stealing hub-caps, setting off fire-crackers) so our friends would remark on our idiot courage. You and I there in Chicago or Los Angeles or Memphis or Woonsocket would be up to some foolishness to intrigue our friends around us. The sound of war did not frighten us because we never heard it. We had no concept of "fire bombing" because we had never been under the bombs.

§ § § In these three stories from the summer of 1940 we find kids playing at war; kids being kids, there would be grandstanding, playing in the shadows, looking for loot in Menton. Calvino and his friends would walk the streets of San Remo in the blackout, playing tricks on the locals by occupying a building downtown, donning gas masks, lighting their masked faces with candles up there on the third floor, causing people to gape, "It it a gas attack? Should we go to the shelter?"

And young Italo and his friend Biancone would run off chortling, because they had so fooled the old folks, with their play war, which always had a happy ending.