The Queen's Caprice

Stories

Jean Echenoz

Linda Coverdale, Translator

(New Press)

We've been fond of Echenoz ever since we reviewed 1914, a short intense study of several young men who are sent off to fight for France at the very beginning of WWI. It was all understatement, made it possible for those of us who think we understand that Great Sad War to see it differently: how it murdered too many too soon, those who had no idea in the world what they were being pushed into.We meet four or five of a whole generation of innocents who, those who were not killed outright, were quickly turned into the walking wounded (physically, mentally).

Now New Press gives us the chance to know Echenoz as a totally different writer, through seven of his brief, very brief récits. They all have the singular mark of one who knows how to build, in no time at all, a tension that ultimately will be spun out in a quick golpe.

Lord Nelson is revealed in six pages --- from his early years to his final hours (buried in a keg of brandy!) The heroic mariner of Trafalgar is revealed to be well-wounded by his line of work. At his death he only had one arm (the other was left at Tenerife) and but one eye (the other planted in Corsica). He was malaria-ridden (from the Indies), drug-ridden (opium --- due to 'phantom-limb' syndrome).

And, such irony: from his first days aboard the various different vessels he served on and mastered, he was plagued by sea-sickness. If you've ever been queasy when you are breezing along on the ocean, just think of making a twenty-seven-year career out of an activity that makes you, daily, weekly, monthly, yearly, want to puke your guts up.

Echenoz let's us meet Nelson at a dinner party in 1802, three years before he was to die at Trafalgar.

Nelson is a small, thin man, affable, youthful in appearance, very handsome indeed but a trifle pale.

"And although he smiles like an actor playing Admiral Nelson, he seems quite fragile, friable, on the verge of fracturing in pieces."

He leaves the dinner party early, not because he is weary, nor because of the excessive attention of the ladies, but because he has a job to do. At the edge of the nearby woods, he digs several holes, and pulls from his pocket a dozen acorns, which he then plants. He does this every time he is on land. "He has set his heart on planting trees whose trunks will serve to build the future royal fleet."

From these acorns he buries will spring the masts, hulls, decks and 'tweendecks of every manner of vessel destined for commerce of the transportation of men --- but warships of all kinds above all: ships of the line, corvettes, armored vessels, frigates and destroyers that will sail the world's oceans long after he is gone, for the greater glory of the empire.

This is the jewel of the seven set pieces of The Queen's Caprice, but each has its own singular pacing, its own power.

Take a train trip to Le Bourget. The author makes three journeys, to get, apparently, nothing more than three sandwiches . . . and a bit of lore. Nothing but simple journeys to a suburb ten km to the northeast of Paris. Yet through detail, Echenoz manages to frame a drama of the change that is so profound for France, where the former colonies are now colonizing the whole countryside, where the heroic past (memorials of the Franco-Prussian War, WWI, and "8 Mai 1945" --- the official end of WWII) are partially vandalized, the people on the street distinctly different from those of even a dozen years ago.There is in Le Bourget the local church, consecrated to Saint Nicholas, which Echenoz describes as "really crummy, so crummy that it became touching." It is the author's way to give us a fairly standard travelogue, which he then jars, sets off with loving touches like, "so crummy that it became touching."

Or this, on the commonplaces of the street, the front page of the newspaper Les Échos, one that asks, "Can One Still Become Rich in France? --- that question in situ, seemed well founded."

I was similarly interested, from another point of view and on the other side of the avenue, by this sticker on the back window of a charcoal gray Mercedes 300D: "Love for all, hatred for none" --- a worthwhile idea at first glance although perhaps a trifle awkward to implement.

Understatement, and a lively, curious mind, very personal, reminding us of the earlier days of The New Yorker in which we were led into a thoughtful, a bit jaundiced, always easy, never bitter, often bittersweet memory, or vision, or thought.

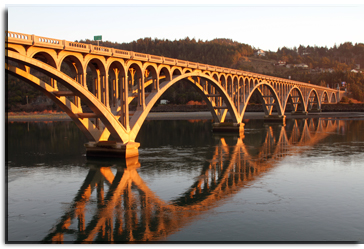

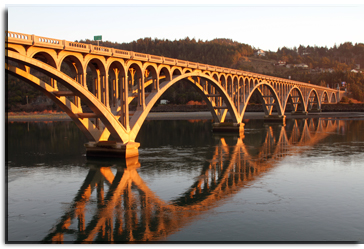

If Lord Nelson's acorns are part of the first jewel in this volume of récits, the center-piece is a history --- a meditation, really --- on bridge building. It is disguised as a short story, about a man named Gluck, who ran his engineering firm for twenty-two years,building bridges, or sometimes dams (which are certainly related to bridges), and at other times tunnels (which are perhaps the opposite o0f bridges) but anyway mainly bridges . . .

In twenty-seven pages, in the company of Mr. Gluck, we are allowed to trace bridges and bridge-building from tree-trunks felled across rivers, to parallel pairs of trunks, stone slabs, bricks, suspension and pontoon bridges, then "recourse to mortar."

At that point, the hardest part was done --- and in large part by Rome, until its empire collapsed and the barbarians arrived who, not building anything, destroyed everything they could.

Because Gluck becomes a student of bridges world-wide, we are allowed to do so too, through the "invention of the lattice girder," then cast iron, then "we decided to invent steel: robust, resistant, ductile steel." With these, we can build new suspension bridges, "their load-bearing capacity allowing them to cross the deepest valleys, the widest estuaries, the mightiest rivers."And I was thinking, in the École Centrale des Arts et Manufactures, where Gluck got his degree in mechanical engineering, if I were a professeur there, at that august institution, a class in bridge-building, I would pique the curiosity of my students on the first day, tell them to study a short but pithy account, by Jean Echenoz, titled "Civil Engineering," so they could immediately get a droll taste of their sometimes tedious profession, with a bit of the history: by a writer who could touch them, perhaps, with, miniatures like,

At the same time, old models were rethought: cantilever bridges, drawbridges, footbridges and other viaducts and we didn't stop until we'd perfected all that, as much as we could, on an Earth given to quaking a thousand times a day, as everyone knows.

--- L. W. Milam