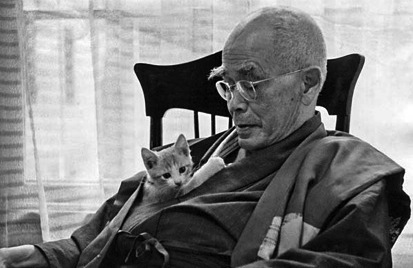

Terrence Keenan

(Wisdom)

Keenan is a Zen Buddhist monk, poet, part-time teacher, and an alcoholic. We find out this in the first few pages of Zen Encounters. He asks who we are. Then, "me? I'm a drunk, an alcoholic. Twelve years ago I went into rehab and have been working at recovery every since."When I finally went for help, I was a tenth of an inch from losing everything --- job, family, life. I have absolutely no doubt that if I had continued as I was I would be dead now.

"This is the real thing. I am not afraid to talk about it but neither do I advertise it." Except on page nine of a book which is part study of his study of Buddhism, part story of his life, part collection of poetry, and completely honest.

It is also a how-to-do-it on the path of Buddhism. Chapter 11 tells the reader how to try to meditate. I write "how to try to meditate," because I am one of about a million people who have tried to meditate about a million times, and always come off as being second-best. Meditation ain't what you think.

Keenan suffered his worst defeat with alcohol. An old Buddhist koan goes, "What is the most important thing in the world." The answer to that, at least according to Alan Watts, is "The head of a dead cat." But Keenan begs to differ. Someone asked him what he wanted out of rehab, he replied, "Peace of mind." But, in addition, he said that he wanted "to live without pain."

Amen to that. As any geezer will tell you, if you wake up without pain, you can be pretty sure that you're in the grave. Keenan is getting on to being a geezer, and now knows that pain goes with the territory . . . .

He also says that another "most important thing in life" is

something you have done all your life, something you still do thousands of times a day without thinking. The most important thing in your life is your breath. Without it you die.

Kennan uses the Breath Question to start us out on the simpliest way to begin to meditate; which is: counting your breath. "You can't not breathe," he points out, and repeats that "one of the oldest, simplest, and best meditation practices is following your breath." Sit in a chair or a meditation cushion, straighten your back, and count your breath. Don't force it. Breathe in. Breathe out (one). Breathe in. Breathe out (two). Breathe in. Breathe out (three). Simple, no?

Some of us never get past three as the mind begins the old merry-go-round, "I've always wanted to be a Buddhist . . . this is great, a snap . . . how could something so simple be so important? . . . hush up, mind . . . are you telling me to hush up? . . . hush! O god, he told me every time my mind starts babbling I have to go back to one. OK: Breathe in. Breathe out (one). Breathe in. Breathe out (two). Breathe in. Breathe out (three) . . .

Keenan includes a fair number of his poems here;. They are simple, direct, a tad out of the self-flagellation school of poetry, not my school. Also, there are countless quotes, some of them wonderful.It is said family members can push your buttons better than anyone else because they installed them.

Or,

There is no recovery pill. Life can only speak life. An alcoholic cannot think his way out of his disease; he has to live his way out.

Or,

Pity and sympathy are not compassion but forms of desire --- desire to help.

And my favorite,

Tai-san . . . what do you think about Nietzche's' 'God is dead?'" This was so unexpected that I was speechless. So Soen Roshi answered, "God is not dead, since he was never born."

Zen Encounters is worth it because we get to journey along the way with someone who knows up from down, who's been in the trenches, who worries (even now) that he is blowing it, who has done so in the past, and has learned the hardest lesson of all . . . at least for those of us who grew up over the last fifty years, despite being winners of one of the biggest crap-shoots of them all: the genetic one. That is, being born and surviving in this particular place (United States of America), at this particular time (1950 - present), with the added advantage of being white, relatively prosperous, and mostly healthy. The extra bonus that Keenan offers us are asides that are absolutely charming, showing us a picture as Matisse or Picasso would, but in words, a few sketch-lines . . . and there it is.

One is a chapter on the work of his sister who teaches deprived children in the Smoky Mountains of North Carolina, classes for those who "fit the stereotype of children who are victims of inbreeding and neglect."

"Mrs. Johnson, we can't do that."

"Oh, yes you can!"

"No we can't. We're too stupid."

"No you're not. I'll show you!"

And she had these kids, labeled by the system as barely educable, doing a conga line along the floor of the trailer, to which their classroom had been exiled, chanting a rap-song of numbers and they stepped back and forth across the figures she had drawn on either side of a line on the floor. By the end of the day they knew how to balance equations.

And, one of the best of the bunch, this passage on the great contemporary Russian writer, Boris Pasternak,

Late in his life, long after he had survived the deaths of such friends as Mandelstam at the hands of Stalin, many years into his own internal exile and enforced official neglect, he was giving a rare public reading. The auditorium was packed with thousands of people . . . At one point, in the middle of a poem he accidentally knocked his sheaf of papers to the floor. Interrupting himself, he stooped to retrieve his poems. A voice in the audience rose, taking up Pasternak's lines where he'd left off. Other voices joined the one. Soon the entire auditorium was resonating with the poem chanted back to the poet. Pasternak stood there, papers hanging from his hand at his side, tears rolling down his face.