Culture and Society in

The Twentieth Century

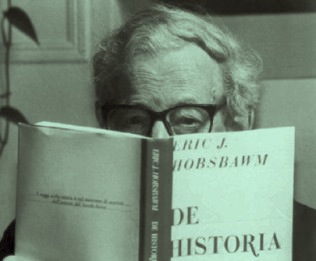

Eric Hobsbawm

(New Press)

Hobsbawm comes across as the master of the historical, at times hysterical, one (or two) liner.

Hobsbawm comes across as the master of the historical, at times hysterical, one (or two) liner.Eric Hobsbawm was a historian of note and a notable Marxist who lived in England until his death in 2012. Fractured Times was published just after and contains twenty-two of his collected speeches, musings, reviews, and articles. They range from studies of manifestos, questions about art and power, the political power of religion, and, most wonderfully, thoughts about cowboys.

- The total number of deaths by gunshot in all the major cattle towns put together between 1870 and 1885 --- in Wichita plus Abilene plus Dodge City plus Ellsworth --- was forty-five, or an average of 1.5 per cattle-trading season.

- Who said: "I've always acted alone like the cowboy . . . the cowboy entering the village or city alone on his horse . . . He acts, that's all." Henry Kissinger to Oriana Fallaci in 1972, that's who.

- The idea that "a man's got to do what a man's got to do" has its classical Victorian expression in Tennyson's now no longer famous poem "The Revenge," about Sir Richard Grenville fighting a Spanish fleet single-handed.

- In later periods of the cattle boom the cowboys were also joined by a fair number of European dudes, mainly Englishmen, with Eastern-bred college-men following them. "It may safely said that nine tenths of those engaged in the stock business in the far West are gentlemen," [Lippincotts Magazine, 1882].

- For most of history, human societies have functioned with populations most of whom were relatively or absolutely ignorant and a good proportion not very bright.

- Even on the eve of the Second World War, Germany, France, and Britain, three of the largest, most developed and educated countries, with a total population of 150 million, contained no more than 150,000 or so university students between them or one tenth of 1 per cent of their joint populations.

- The classical bourgeois concept of "the arts," though carefully preserved in its mausoleums, is no longer alive. It reached the end of its road as early as the First World War with Dada, Marcel Duchamp's urinal and Malevich's black square.

- At the end of our millennium there are three types of building or complex that are suitable as new symbols of the public sphere: first, the large sport and performance arenas and stadiums; second, the international hotel; and third, the most recent of these developments, the gigantic closed building of the new shopping and entertainment centers.

Hobsbawm is a blessed writer and has the ability to pull together so many diverse elements of culture that one is reluctant to call him merely "an historian." He tells us that the best visual art in Russia is the Moscow Underground, "the Metro being probably the largest artistic enterprise undertaken in Stalin's Soviet Union." He compares that subway system to American movie-houses of the 30s --- "to give men and woman who had no access to individual luxury the experience that, for a collective moment, it was theirs."

He tells us that Henry Kissenger thinks he is a cowboy, as did Reagan, the two of them out there on the lone prairie, firing off six-shooters and waving their cowboy hats and protecting Western towns and women from the bad guys (and, presumably, Marxists like Hobsbawm). He also has a breathtaking ability to take something that the rest of us may just observe in passing, and offer it up as the sign of a profound change.

For instance, this on the burka: "The useful and visible sign of the rise of fundamentalist Islam is the growing and, in the new century, probably increasing tendency of women to wear the all-covering black garments of this orthodoxy." Every page here manages to contain a pleasant surprise offered up by a classically trained historian who apparently delights in taking a contrarian view of what most of us merely observe.

In one chapter, he notes how scientists were treated by the three main combatants of the Second World War. By murdering or driving Jewish scientists from Germany, Hitler crippled his country's scientific power --- in effect, delivered it to England and the United States. In the same way, by declaring that the theories of T. D. Lysenko "were officially declared correct, materialist, progressive and patriotic against reactionary, scholastic, foreign and unpatriotic bourgeois genetics," Stalin forced Russian science into a dead-end. This was fatal in the case of biology and genetics, for it was a time when the country desperately needed the knowledge that could have helped to end the famines of the 30s, brought on by Stalin himself. In addition, notes Hobsbwam, "some three thousand biologists promptly lost their jobs, and some their liberty."

§ § § Hobsbwam is at his most succinct when he concentrates on the rise of fundamentalist ideologues, mostly Protestant Christianity and traditionalist Islam. These are "religions of the book . . . a return to the simple text of their scriptures, thus purifying the faith from its accumulated accretions and corruptions." These are what you would call radical religions, and their revival began at about the same time, over the last half-century.

He points out that if you had opined that fundamentalist Christianity as having any political power in 1960, you would be wrong; if you thought it did not have political power ten or fifteen years later, you'd be dead wrong.

Like Islam, this movement has widened or even created a cultural gap in countries of the older industrial revolution in Europe . . . as well as those of South-East and East Asia and the regions of Africa, Latin America and west-central Asia.

It depends on the "collective recreation of 'rebirth' by powerful individual spiritual experiences and emotionally satisfying, often ecstatic rituals."

A study of Pentecostals in ten countries showed that 77 - 79 per cent in Latin America and up to 87 per cent in Africa have witnessed divine healings, while 80 per cent in Brazil and 86 per cent in Kenya have experienced or witnessed exorcism.

"If contemporary fundamentalists followed the logic of the Anabaptist ancestors, they should forgo any technological innovation produced since their foundation."

But the new Pentecostal converts do not shy away from the world of Google and the iPhone: they flourish in it. The literal truth of Genesis is propagated on the internet.

On the other hand, Islam's radical revival --- what he refers to as "the Bedouin puritanism of the Wahhabi version of Islam" --- probably came into being with "the USA's Cold War backing of the Muslim anti-communist fighters in the USSR's Afghan War." The Wahhabi version of Islam, provides religious bona fides that maintain its political stability.

Its immense oil wealth has been used to finance the vast expansion of the Mecca pilgrimages and the mosques as well as religious schools and colleges all over the world, logically enough, for the benefit of the intransigent Wahhabite (Salafite) fundamentalism that looks back to the founding generations of Islam.

Hobsbawm cleverly avoids overtly stating that the astounding new growth of these two fundamentalist religions may be leading us implacably, stealthily, and relentlessly into a new and virulent Holy War. But Pope Urban's First Holy Crusade in 1095 and the subsequent six invasions are well remembered as vicious blood-baths by Islamites to this very day.

This collective memory of a Christian-inspired holocaust from a thousand years ago makes a new conflagration well within the realm of the possible . . . an international firestorm that might be as damaging to western culture and vision of "progress" as any conflict in the world's brief history.

As Hobsbawm artfully concludes,

The theocratic authorities in Iran base their country's future on nuclear power, while their nuclear scientists are assassinated with the most sophisticated technology wielded from war-rooms in Nebraska, very likely by born-again Christians.

--- A. W. Allworthy