Death of

The Dülger

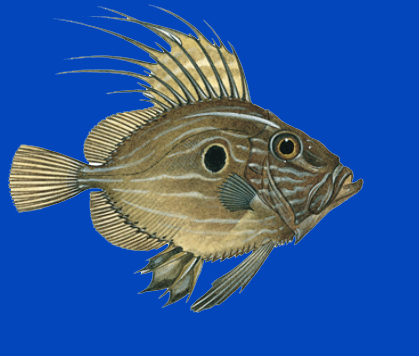

They all have beautiful eyes, and when they're still alive you might imagine their scales on a woman's dress, or pinned to her breast, or dangling from her ears. Forget diamonds. Forget rubies, emeralds, and carnelians. There isn't a gemstone in this world that can outshine these scales.If they could, women would waltz into ballrooms flashing this living iridescence; fishermen would be millionaires and fish would have all the glory and fame. But the moment a fish dies its scales go dull, until it's as gray as an old doll. Unless, like the fish in this story, it had had no burning, shimmering scales to lose. The poor thing had no scales at all. The Dülger is olive brown with a light, faint touch of green. It's the ugliest fish in the sea, with an enormous, toothless mouth that glistens translucent white, like nylon. It spreads open wide the moment it surfaces; and once its mouth opens it never closes again.

Did I say that it's a dirty olive brown? And as flat as a pancake? Did I say it has two dark spots on either side that look like fingerprints?

Once upon a time the Dülger was a terrible sea monster: it wreaked havoc on the Mediterranean long before the birth of Jesus Christ. After which the Greek fishermen began calling him Hrisopsaros, Christ's Fish. Woe to the Likyan who slipped overboard. Who knows how many Carthaginians the Dülger dragged into the sea, how many Jews it tossed up into the air? It sliced them and diced them and chopped them into bits; it threw them in the air and poked them and stabbed them. It pummeled and battered them and tore them into pieces. The Dülger was the most fearsome creature in the Mediterranean, and pirates, undaunted by man, beast, lightning, rain, misfortune or torture, turned white upon hearing its name.

One day Jesus was strolling along the seashore when he saw a group of fishermen abandoning their boats. He could see that terror had gripped them. "What's the matter?" he asked. "Oh Lord," they cried. "We've had enough! Enough of this monster! It's dashed our boats and ripped our people to shreds. And the worst of it is that we no longer dare go out to fish. We are doomed to go hungry and die."

In his humble robe, Jesus stepped toward the sea that was the raging Dülger's domain. Pinning the largest between his long fingers, he pulled it up out of the water, and, pinching it tightly, he bent over and whispered something into its car.

And from that day on, the Dülger has been a meek and rather miserable creature, its frightful appearance notwithstanding. For the Dülger is covered in protrusions that might be mistaken for nails or files, or chisels, adzes and saws. There are even bulges that resemble pincers, and there are thorns of all sizes between its bones. Surely this is how the Dülger came to be called the woodworker fish in Turkish.

Its motley collection of tools is covered by that membrane you might take for clear nylon. It is paper --- thin and gets a little thicker, a little darker, toward the tail, which is much like that of any other fish.

The instant a Dülger bites your line, it's at war with the world and the sea. We can only imagine its fear. It has already left its world behind. Even if it breaks free from the line, it'll just lie there flat on the water's surface, its wide eyes staring mournfully. Then you'll pull it up into the boat and for many minutes you'll listen to it wail. Oh, that moan. Only the Dülger and the Red Gurnard give out this pained cry. As they lie dying on the boat, they wail and gasp. When a net falls over a Dülger, it is fury incarnate.

One day in front of the fishermen's coffeehouse, I saw a Dülger hanging from an acacia tree newly blooming with white and red blossoms. It was dark brown, as if it had just come out of the sea. And it seemed entirely still, as lifeless as a stone. But I thought I caught its paper-thin membrane quivering over all those tools, as soft as silk. I'd never seen such a dance, yes, that's what it was, a dance: it was the dance of an invisible inner breath. But the body was lifeless, utterly lifeless: only the membrane was trembling, shivering with pleasure and delight. This was a dance of death. It was as if its soul was leaving its body in little breaths, slipping through its paper-thin membrane, leaving not so much as a whisper behind.

You know the way a ripple will cross the surface of the water on still summer days. That was how it looked to me. But the fish was dying, so perhaps these were tremors of pain. Perhaps we would prefer not to know. It was, after all, an extraordinary way to die. Did the fish believe it was still underwater, swimming happily along the sea floor? Night had fallen. It could feel the sand tickling him. The eggs were there and the male seeds were swaying in the waters above, or so it thought. It was seized by a moment of lust. Then, to my horror, it slowly began to fade, casting off its color, turning ghostly pale. Or did it just seem that way? Was it really changing color? No need for me to take a closer look --- I knew I was right.

The edges of its membrane along its sides began to quicken the dance and from one second to the next turned even paler. I could sense the fear in its heart, a fear that we all know: the fear of dying.

Now it knew. Its life at the bottom of the sea was no longer. Its flat body would never again drift: through the currents, or bury itself in dark waters and green seaweed. It would no longer wake in a cool light showering down from the surface, or splash its tail about in the dance of green and blue daylight, casting off its seeds before racing to the surface. No more dozing in the iridescent seaweed, no more rubbing that set of tools against barnacles for a good cleaning. It was all over.

The Dülger took a long time dying. It was as if it were trying to accustom itself to the collection of gases we know as air. If it could have just held out a little longer, it might have made it.

If only we could have just drawn out its death throes from two hours to four, and then from four to eight, and from eight to twenty-four. If we'd managed that, we might even see a Dülger working among us one fine day.

And what a celebration we'll have, the day he can at last breathe our air and drink our water. We shall see at last that, despite his gross and gruesome looks, he is actually quite a calm and timid creature, sensitive and good-hearted by nature, with a soft and hesitant demeanor. He'll become one of us. We'll praise him and do our best to make him happy. He'll find it all a little strange at first, but he'll do his best to fit in. Then one day we'll turn him into a frustrated, misunderstood poet. And the next day we'll slander him and run him into the ground. The day after we'll harangue him for being too sensitive. The day after that, we'll harangue him for loving us, and on the last day we'll accuse him of his cowardice and silence. One by one, we'll pull out all the beautiful things inside him and toss them aside. We'll sneer as we chip away at those two fingerprints with his ax, his saw, his file, his adze, and nails. And he'll become the monster that he was at the dawn of time.

Once we get him hooked on our water, we'll leap at the chance to change him back into a monster.

---Death of the Dülger

Sait Faik Abasiyanik

From A Useless Man

Translated by

Maureen Freely

and Alexander Dawe

Archipelago Books

232 3rd St., #A111

Brooklyn NY 11215