World War I

In 100 Objects

Peter Doyle

(Penguin)

It is certainly odd what people will fabricate to murder each other, especially in times of war. There is (or was, for World War One) exotic hardware --- bombs, rifles, machine-guns, flame-throwers, gas projectiles, howitzers, Very lights, mortars --- you name it.Author Doyle has here come up with several dozen oddities to make WWI out-of-this-world, or at least take it away from the trenches. Alpine crampons for fighting in the mountains between Austria and Italy. A special Ottoman belt buckle for the Turkish soldiers serving in the Mediterranean, with red fez (they were known as "Johnny Turk" by the Brits). Liverpool "Pals" --- special badges for the recruits from one area (usually poor dogsbodies from the lower classes) who signed up together, coming from the same town or neighborhood.

There was a postcard circulated in France called "Les Poilus" showing three soldiers --- quite hairy, thus the name --- that were said to represent the common man in the field. There was the common puttee, a nine-foot reinforced strip of cotton or wool wrapped from ankle to knee to protect against the bitter cold (and the ever-present mud) in the trenches. A Wolseley helmet --- what we would later called a pith helmet (another gift of colonialism) --- that came into being during the Boer War and was vital protection in WWI against the sun in the southern battlefields such as Basra and Baghdad. Who'd ever guess we'd get to meet these names again, a mere 100 years later: love may come and go, but the love of war, and its impedimenta, never disappears. Thus this book.

The real meat here comes with the exquisite full-page photographs of cannon, gas projectiles, bombs, shells, pistols, knives: the Khukuri knife of India ("intended primarily as a chopping tool"), the Lee-Enfield rifles (English), the Mosin-Nagant rifles (Russia), the French 75 cannon (officially the 75mm gun Mle 1897):

The 75mm shells it fired were all equipped with time fuses . . . [which] fired antipersonnel shrapnel shells that would spread a hail of spherical bullets onto oncoming infantry.

In addition, there are certain objects, looking relatively harmless, yet filled with grisly associations for those who had to live with them. Such as the Gas helmet looking like a hood from an old horror movie [See Fig 3 below]. This was sewn to counter the first gas attack launched by the Germans at Ypres in 1915, mostly of chlorine which "kills by irritating the lungs so much that they are flooded, the victims actually drowning in their own bodily fluids," literally making one turn blue:

Men killed by gas show startling blueness of the lips and face, a function of the blood becoming starved of oxygen.

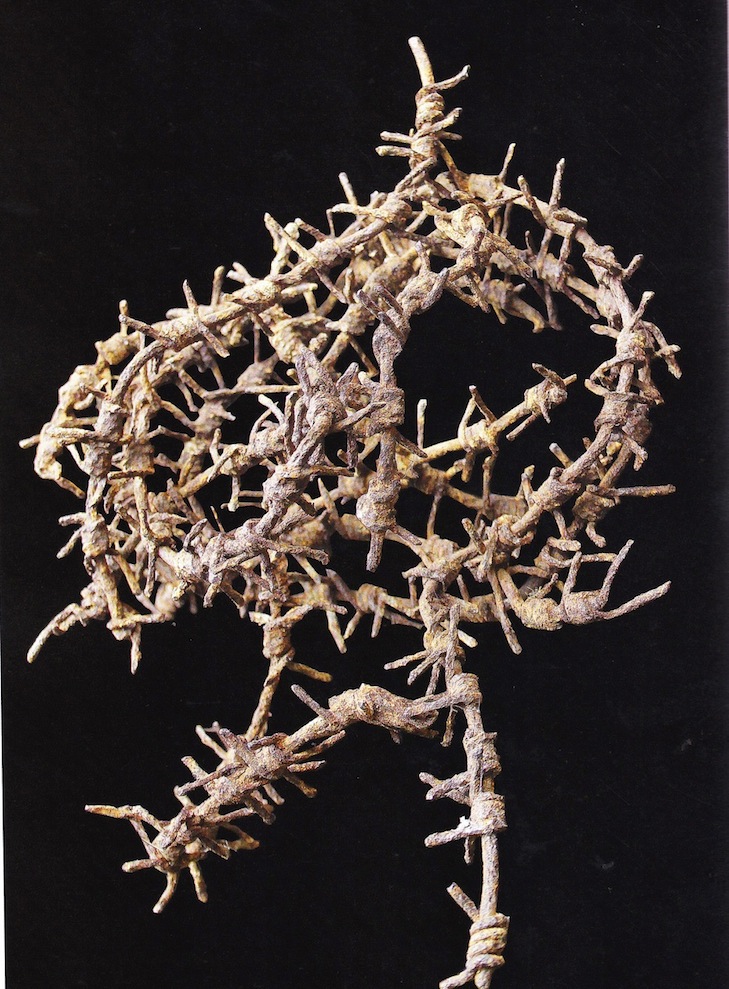

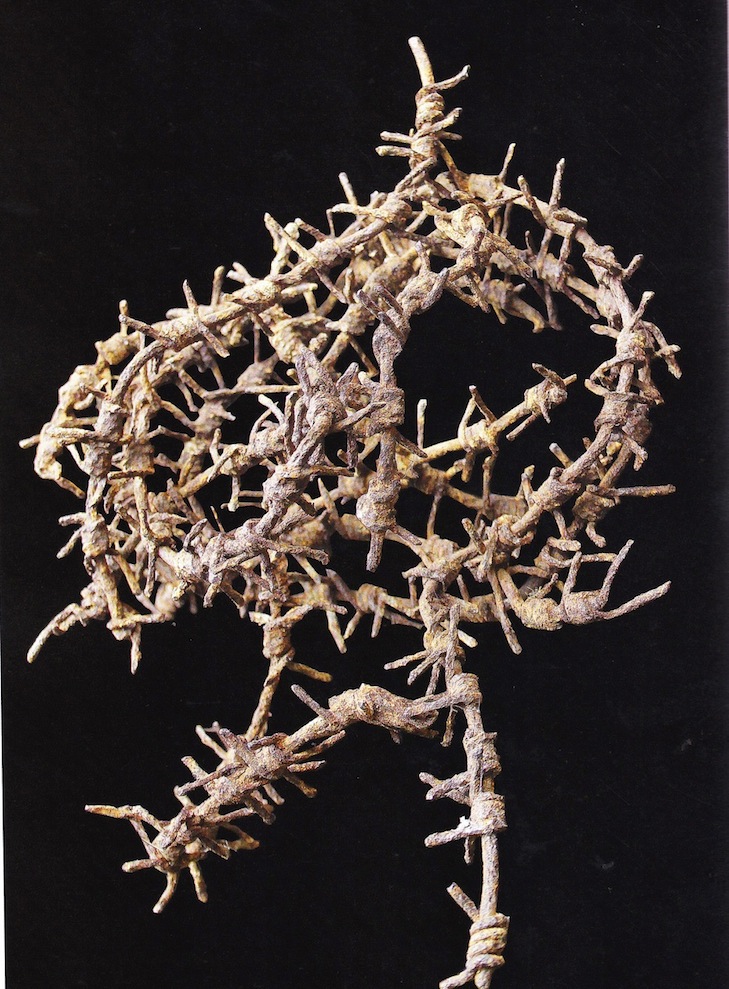

More subtle oddment is a short squiggle of rusted metal identified as barbed wire. [See Fig 1 above.] It was ubiquitous. Reginald Farrer wrote, "Remember the work that every length of this wicked weed had done --- the dead and dying caught in its merciless mesh, and kept hanging on its thorns for hours and days." The soldiers in the field had a more direct if not less poetic riff, complete with missing soldiers "hanging on the old barbed wire:"

If you want to find the old battalion,

I know where they are

They're hanging on the old barbed wire,

I've seen 'em, I've seen 'em,

hanging on the old barbed wire.

I've seen 'em, I've seen 'em,

hanging on the old barbed wire.There is a fine mini-history of these mechanical entanglements here, beginning with barbed wire's origins on the plains of the American west in the 19th Century; its first use in the Russo-Japanese War of 1902 - 1904; and its high recommendation in a British war manual of 1908, saying it "would not be much damaged by the enemy's artillery," and

wire entanglement is the best of all obstacles, because it is easily and quickly made, difficult to destroy, and offers no obstruction to view.

Its placement and upkeep might confuse one into thinking it was a rare garden ornament, one that needed to be tended only by night, replacing the open links . . . or preparing for an assault by shearing for an upcoming possible advance. "Wiring parties on both sides would enter no-man's-land under the cover of darkness, in patrols of two to three men, to inspect the integrity of the defenses or cut paths through their own wire in preparation for a raid or in larger fatigue parties to repair and improve the front-line wire."

Such parties would be in a constant state of readiness; any noise would trigger off a flurry of star shells and Very lights intended to illuminate the interlopers, picking them out in stark silhouette against the night sky, an easy target for a sweeping machine gun or targeted artillery barrage.

World War One brought in a bounty of inventions, and many are shown here, although some not as macabre as the those we have selected above. There are the funny looking airplanes like the French Spad XIII, not so different tfrom crop-dusters of today, with lots of wing-span so that it could move slowly over the front lines, or even penetrate into enemy territory. The early ones with elegant colors for the different parts look almost like butterflies. There are more mundane objects --- water bottles, medals, scrapbooks, soccer balls, funny old posters. All, glamorous or no, make their way into World War I in 100 Objects as do other oddities. Like holes. Big ones. In the ground. The Lochnagar Crater, created by a shaft bored in from English lines under the Germans lines at the Somme, ultimately stuffed with 60,000 tons of explosives and set off in 1916, creating mayhem above. (The crater still exists near La Boisselle, France, though with grass and trees, looking, we suspect, more benign than it did in late 1916.)

Paging through this fascinating and well-illustrated book, one is still left wondering about that one object that is not illustrated, which should have been the center-fold. It would be a photograph of the pernicious thought-bags, the little pea-brains resting in the noggins of the heads-of-state, the political leaders who were in charge of the thirty countries of the Entente and the eight countries of the Central powers, those that decided to embark on this disaster, proclaiming to all that it would "be over by Christmas." Which Christmas? They never said.

The skulls that would need to be examined exhaustively would include those of Nikolai Alexandrovich Romanov of Russia, Raymond Poincaré and Georges Clemenceau of France, H. H. Asquith and David Lloyd George of the United Kingdom, Victor Emmanuel III of Italy, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, Said Halim Pasha and Ahmed Izzet Pasha, Grand Viziers of Turkey and Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany. The last who, we are told, after viewing the trenches in 1915, said Ich habe es nicht gewollt --- "This is not what I wanted."

We would suggest complete biological tests of the remains of these who pursued a violent, savage, vicious, insensate, mind-destroying, soul-warping, humanity-wrecking, heart-ripping series of military engagements beginning in the early fall of 1914 that went on day-after-day, month-after-month, year-after-year, summer and winter, for over four years, four months, and four days; a spirit-wrecking agon; a mortal and spiritual and humanitarian break-down astounding in its animal force, one that made it possible for people from civilized nations to murder and wound each other, some 16,000,000 dead, another 30,000,000 maimed for life --- a lingering trauma to the western world that also managed to destroy tens of thousands of artifacts of civilizations from centuries past, centuries of culture and wisdom --- and, in the process, permanently ruin the hopes of so many innocents, ruining the spirit of so many for so many decades to come.