The Kenyon Review

Poetry, Stories,

And Essays

David H. Lynn, Editor

(Sourcebooks)

These literary anciens who run the "the little magazines" --- The Virginia Quarterly Review, The Midwest Review, The Sewanee Review, the Hudson Review, The Kenyon Review --- are not unlike the choirmasters from a hundred years ago whose job was to find the best boy singers, take them to the local surgeon for a quick snip, and thus render them bland counter-tenors for life. In like manner, the editors of these little magazines take what comes in the mail and get to work to do whatever is necessary to render the poems dispirited and the prose lifeless.It will always be beyond me how they can exist in the fascinating world of American letters --- but end up publishing "product," something out of MacDonald's or Walt Disney or CheeseWhiz. Poems and prose are emulsified, bleached and toned, and then squeezed lifeless by the editor's steam iron, creating a bland mishmash such that one wants to let the magazine drop from nerveless fingers, plop to the floor to lie there alongside the doghairs and fleas and slutswool that inhabit the nether regions.

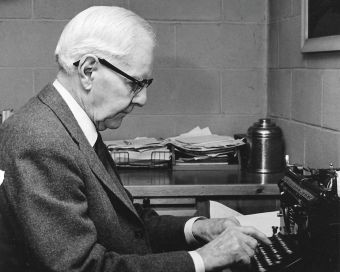

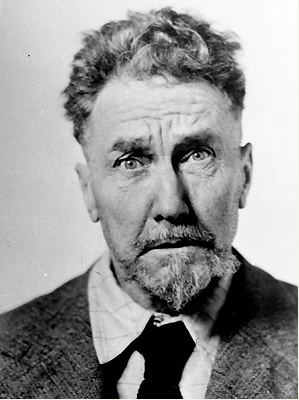

Despite their cant, these magazines are quick to reject the experimental. John Crowe Ransom founded The Kenyon Review in 1939 and acted as its editor until 1959, establishing its reputation as "one of the finest literary journals in America," says editor Lynn, modestly.

While regarded as a conservative critic, Ransom often published writers whose values and aesthetics were very different from his own.

Right. Ask authors like Henry Miller, Lawrence Durrell, Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, Charles Bukowski, Mordecai Richler, Philip Roth --- not to mention James Baldwin, Richard Wright, Claude Brown et al --- all writers with life and heart and a clear, strong voice. Ask them or their biographers how easy it was to get into The Kenyon Review under Ransom.

I suggest they knew early on --- especially if they were black --- that they would get no hearing nor space from any of these WASPy little magazines. The real tragedy was that an appearance here could easily have spelled the difference between success and failure to these often impoverished authors who desperately needed exposure. These writers got stiffed, and stiffed repeatedly, by the intellectual bag ladies who were interested merely in the stars of the American Literary Pie, those with white skin, rhyming verse, and nerveless prose.

The Kenyon Review has managed to prevail all these years by publishing this acceptable cream of American writing, and this fat volume (440 pages!) is evidence, your honor, of my brief. In the case of the Kenyon Review, it might have to do with being forced to emit its dim light from the feeble wastes of Godforsaken Gambier, Ohio.

Editor Lynn modestly calls this "an extraordinary anthology," but despite all the names (and name drops) --- James Dickey, Galway Kinnell, Derek Walcott, Ha Jin, Joyce Carol Oates, Charles Wright, John Berryman --- the usual heavies of the American Lit Biz, the word "extraordinary" need not apply. The ones above, along with Schwartz, Lessing, Nabokov, Beckett, Walcott, Lowell, Calvino, Berryman, and Rukeyser are uniformly represented by their weaker wares.

The reason is obvious. Once authors attain a modicum of fame, they wouldn't be squandering their words on the likes of The Kenyon Review. It is no accident that the circulation of the magazine over the years has never risen much above a few thousand.

Here we find a juvenile piece from Dylan Thomas (1940), a terribly translated poem from García Lorca (accented "i" somehow mislaid), a not so very inspiring poem of Nabokov ("Tell, flier, why your lips do lack/a tint of life...") dated 1979 but actually composed fifty years before --- a poem that not even Joseph Brodsky's translation can salvage. There is one mildly interesting offering from Sylvia Plath, dated 1960, but it would probably be meaningless if we didn't have the knowledge of her life with poet Ted Hughes and her own sad demise.F. Scott Fitzgerald is represented here by "The World's Fair" dated they tell us 1948 even though he passed on to his own world's fair in 1940. It's an excerpt from his never-

John Berryman (1940) is included ("Becket's brains upon the pavement spread/Forbid my rust, my hopeful prophecy") along with the ironical if not mischievous editor's note that he jumped off a bridge in Minneapolis in 1972. And of course, since we always need the copyright notice of American literary success, that being the heavy of all heavies in the lit-biz --- Joyce Carol Oates --- we have four pages (Introduction) and twenty pages ("Death Mother") of her prose, which, surprisingly, isn't all that bad, considering that it was whipped off in an afternoon between gigs on several literary panels and evening classes spent explaining the roots of American letters to the dumbfounded students at Princeton University.published fourth novel, and since we all know that his writing turned pale and meaningless in the last years of his life, it is obviously included not because of its innate quality --- it has none --- but because a reader will see "F. Scott Fitzgerald" in the table of contents and think, "The Kenyon Review even published F. Scott Fitzgerald." Wow. An endless meditation on snakes from the Mr. Softee of American Verse, Wallace Stevens, takes up some nine pages. There are two poems by Robert Lowell, and we know he is a Very Important Poet because the editor's notes are printed on page 57 and repeated without change on page 69.

John Crowe Ransom founded The Kenyon Review which may explain its lack of nuts. He and the other dandys out of the New School of Criticism turn up early on in the book, including Allen Tate with a poem that starts off, unappetizingly,

The Management Area of Cherokee

National Forest, interested in fish,

Has mapped Tellico and Bald Rivers

And North River...Small literary magazines like this one have pretended over the years to be a place where the new and young and untried will be heard. In truth, they exist to plump up the lorky egos of the fossils in the English Departments who, having failed at their chosen craft --- being creative or being writers or being creative writers --- end up as editors. Thus The Kenyon Review and its ilk become not a hothouse of experimental literature but a sinecure for the frumpy literary failures who abound in these departments around the country --- men and women who live in a perpetual Brown Study of ennui, wheezy memories, and desuetude.--- H. Washington Frazier, Jr.