Carol Ann Duffy

(Faber & Faber)

Rhymes and kisses aside, Ms. Duffy has some strange images that may give some readers not only heartburn but chilblains. Several of the more scenic include "the olive trees ripening their tears in our pale fields," "the Oscar-winning movie in your heart," and the winner buy a landslide, "Two juggling butterflies are your smile..." In order to come up with an image, Ms. Duffy seems not only willing to lean out of the catamaran but is ready to go overboard with the fishies.

She brings to mind that old rascal Joyce Kilmer who displayed a similar case of poetic astigmatism:

- I think that I shall never see /

A poem lovely as a tree./

A tree whose hungry mouth is prest /

Against the earth's sweet flowing breast...

Since poems are meant to be read and not seen, the image doesn't exactly fly. Ms. Duffy maybe bests that by writing "Learn from the winter trees, the way / they kiss and throw away their leaves, / then hold their stricken faces in their hands / and turn to ice."

review

George Bradley, Editor

(Yale)

The main problem with YYP is that it has traditionally missed the boat, the huge and noisy boat that sails around and about, loaded with the true artists in the poetry world. Sylvia Plath applied to be a Yale Younger Poet but was turned down. The Beats didn't have a chance --- except for the obscurantist Jack Gilbert. Most of the true geniuses of the 20s were ignored.

Bradley says in his exhaustive and exhausting introduction to The Yale Younger Poets Anthology (100 pages out of 300!) that the YYP is "resilient and various" with America's poetry being "one of the nation's significant contributions to world culture." We doubt it. The absence here of Gertrude Stein, T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, Allen Ginsberg, William Carlos Williams, Randall Jarrell, Judson Jerome, Karl Shapiro, David Wagoner, Gary Snyder, Howard Nemerov, X. J. Kennedy, Sylvia Plath, Lew Welch, and hundreds of minor masters is a potent condemnation in itself.

It means that the judges of this very prestigious, well-funded and highly publicized vehicle were and are and probably always will be out- Those who did make it (for example, Oscar Williams, John Hollander, and John Ashbery) are well represented here, along with some now-forgotten and very grim poetasters like Reuel Denney, Edward Weismiller, and Louise Owen ("So, here, tied in that crooked line,/that is the North Wind,/trapped --- and mapped!")

review

Louise Glück

(ECCO/HarperCollins)

It came to us very late:

perception of beauty, desire for knowledge.

And in the great minds, the two often configured as one,

we find ourselves humming along, a contented bee, feeling like we're in the middle of a course on the History of Civilization, there in Williamstown --- Civilization, without any of its discontents.

We've often contended that poetry worth writing home about has to be wrapped up in a whoosh of words --- maybe like Donne's wonderful strange lines,

I long to talk with some old lover's ghost

Who died before the god of love was born...

or

Busy old fool, unruly sonne

Why dost thou thus...

Perhaps (we're thinking), it's time for Ms. Glück to take a year off --- to do the sabbatical in Vail, or Virginia City, or Vancouver --- wherever the hell tired-out poets go to get back in touch with the world, or with themselves. Perhaps, out of the hubble- Perhaps in Venice, or Victoria, or Vienna, she could have a chance to renew acquaintance with some of the language masters: e e cummings, Edward Thomas, the Bard himself, say --- all those who are in it for sheer hypnotic music, music we don't find much of when we read Time was passing. Time was carrying us The onions! The potatoes!

faster and faster toward the door of the laboratory,

and then beyond the door into the abyss, the darkness.

My mother stirred the soup. The onions,

by a miracle, became part of the potatoes.

review

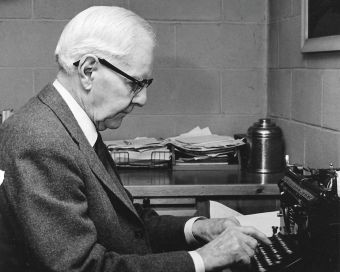

Louis Untermeyer, Editor

(MetroBooks)

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Rage rage against the dying of the light...

It was enough to make us give up our aspirations, to wonder how we had ever thought for a moment that we could spend even a day in the parsing of such silly verse fabrications as those oozed out by Walter Savage Landor, George Meredith, Francis Thompson, Edwin Arlington Robinson.

review

Wallace Stevens

J. D. McClatchy

(Random House Audio)

After a little bit I came to a stop-light and as Stevens and I were dreaming along about happy people in an unhappy world and unhappy people in a happy world and, perhaps in bliss, my foot slipped off the brake and I did a little collateral damage to the truck in front of me. Leaving "the metaphysical treats of the physical" and the motor running, I met nervously with a burly fellow in the Black Darth Vadermobile in front and I must say he was quite good about it all, quite understanding when I told him about the happy people in a happy world, and thus, instead of one of those dreadful insurance company claims what with the police and everything he agreed to take a few loose twenty-dollar bills off my hands that I wasn't using anyway.

I am reluctant to tell you, as you will think I am some kind of what we used to call a "prole," but I have to confess to you that in listening to Stevens perhaps I am listening to one of the great unsung masters of American verse --- but maybe I am listening to nonsense.

Am I dense or is he putting us on? --- this well-dressed man who spent all his life as head of the claims department for Hartford Accident and Indemnity. I can see him now, in his Brooks Brothers suit, striding up the streets of Hartford --- or was it New Haven? --- full up in his brown study, thinking, mouthing the words so when he gets to his neat office on the 19th Floor he can hitch up, sit down, and dictate his poems to his secretary (swearing her to secrecy, they don't care much for iambs there at Hartford A & I) --- and then after a few months, he has Miss Potts (that's her name) collect them together and he labels them and sends them out to his publisher. He did this patiently, regularly --- for twenty-five years.

review

A Winter Journey in Poetry, Image, and Song

John Harbison

Susan Youens

(University of Wisconsin Press)

It takes a certain suspension of disbelief to get through this balderdash. To devote any time at all to the verse of his librettist Wilhelm Max Müller --- much less an entire volume --- is a grave mistake. Performers know this well. I have yet to hear someone sing these songs in English without breaking down or breaking up. In German it's just bad poetry; in English it's a howl.

For the CD that accompanies this volume the editors enlisted one Paul Rowe to sing these songs. I've never heard him perform before and I hope to never again. I am crazy about the "Winterreise," but I had to take this one off the CD player after Wasserflut, "The Flood." It was up to my knees. In keeping with the mood of Müller's musings, Rowe decided to go pale, thin and wan; he ends up sounding like one in the throes of a pneumothorax.

If one wants to hear the Winterreise with its necessary vigor and tragedy, exquisitely restrained, one must seek out the bellwether, the cycle as performed by Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, accompanied by Gerald Moore. It's available on EMI. Fischer-Dieskau manages to con us into forgetting the lyrics, makes us concentrate on the music. Moore, as experienced an accompanist as there ever was --- he once wrote a very funny book about just such a job --- is quick, precise, and at the height of his powers in the 1962 recording.

review

Poetry, Stories, and Essays

David H. Lynn, Editor

(Sourcebooks)

These literary anciens who run the "the little magazines" --- The Virginia Quarterly Review, The Midwest Review, The Sewanee Review, the Hudson Review, The Kenyon Review --- are not unlike the choirmasters from a hundred years ago whose job was to find the best boy singers, take them to the local surgeon for a quick snip, and thus render them bland counter-tenors for life. In like manner, the editors of these little magazines take what comes in the mail and get to work to do whatever is necessary to render the poems dispirited and the prose lifeless.It will always be beyond me how they can exist in the fascinating world of American letters --- but end up publishing "product," something out of MacDonald's or Walt Disney or CheeseWhiz. Poems and prose are emulsified, bleached and toned, and then squeezed lifeless by the editor's steam iron, creating a bland mishmash such that one wants to let the magazine drop from nerveless fingers, plop to the floor to lie there alongside the doghairs and fleas and slutswool that inhabit the nether regions.

Despite their cant, these magazines are quick to reject the experimental. John Crowe Ransom founded The Kenyon Review in 1939 and acted as its editor until 1959, establishing its reputation as "one of the finest literary journals in America," says editor Lynn, modestly.

While regarded as a conservative critic, Ransom often published writers whose values and aesthetics were very different from his own.

Right. Ask authors like Henry Miller, Lawrence Durrell, Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, Charles Bukowski, Mordecai Richler, J. P. Donleavy --- not to mention James Baldwin, Richard Wright, Claude Brown et al --- all writers with life and heart and a clear, strong voice. Ask them or their biographers how easy it was to get into The Kenyon Review under Ransom.

I suggest they knew early on --- especially if they were black --- that they would get no hearing nor space from any of these WASPy little magazines. The real tragedy was that an appearance here could easily have spelled the difference between success and failure to these often impoverished authors who desperately needed exposure. These writers got stiffed, and stiffed repeatedly, by the intellectual bag ladies who were interested merely in the stars of the American Literary Pie, those with white skin, rhyming verse, and nerveless prose.

Go to the full

reviewThe Collected Poems of

Muriel Rukeyser

Janet E. Kaufman

Anne F. Herzog

Editors

(University of Pittsburgh Press)The University of Pittsburgh Press thinks enough of Muriel Rukeyser to pull out a fat 600 page volume with 600 or so of her poems beginning with her earliest volume of poetry, Theory of Flight from 1935 down to her last which came out in 1976 The Gates plus some odds-and-ends left over. And we have spent some time rummaging around here breathing a sigh of relief thinking about the advantage of reviewing a book of poetry or essays over a 600 page novel, because you can poke around in a fat volume of poetry and it's like being at a farmer's market, you can pinch the merchandise but you don't have to buy anything if you don't want; you can pick and choose and in the case of one of these not-so-well-known poets you can get at least some idea of what he or she thought he or she was about and what he or she wanted to get across and how good he or she was at it.Sometimes these junkets to the streetside Book Dumps pay off. Big. Awhile ago, we came across a collection of the poems of Howard Nemerov and we were moved to write

It's the first time since college that I took a book of poetry to bed with me: that's how chummy we got, me and this Nemerov. I read him through, first to last; slept, woke up, read it back to first, marking the pages, wondering "Where has he been all my life?"

However, not to wax too hopeful in the junk-yard of our lives (and verse ... and vice-versa), not long before that we had a quite dissimilar visit with Yvor Winters who, despite all the tweeds and end stop lines and the smoky fall weather and pensively falling leaves in New England was, we concluded, a humbug ...Go to the full

articleThe Madness of Art

Interviews with Poets and Writers

Robert Philips

(Syracuse University Press)Over the last twenty years, Robert Phillips has interviewed writers and poets for The Paris Review. He includes eight of these here --- including ones with Philip Larkin, Joyce Carol Oates, Karl Shapiro, William Jay Smith and William Styron.God knows why anyone in their right mind would want to interview these characters, much less read an interview with them. If someone is a worthy writer, we should be spending time with their books, not wasting it on questions about where they went to school and who influenced them and what they do on weekends and what they have for breakfast and most of all, what they think about their own writings.

Most real writers stay the hell away from these arty interviews. Vladimir Nabokov loathed critics and strenuously avoided those who wanted to ask him dopey questions like "Tell us about the sources of your inspiration" and "Is there a person who was your model for Humbert Humbert?" and "Did you have a happy childhood?" We can see one of these interview ninnies turning up in the early 17th Century asking Shakespeare whether his father loved him, and whether he named Hamlet Hamlet because of the death of his own child Hamnet, and why he only left his wife his second best bed and what exactly did he mean anyway by the lines "To be or not to be..."

If you want to be driven mad (or, still, after all this time, have that fake romantic notion about "The Madness of Art"), I suppose this would be your book. All it proves to me is that Joyce Carol Oates in live interview is just as arrogant and unseeing as the characters in those low-life novels she churns out like hot dogs, she being the Oscar Mayer of what's left of American literature.

And William Styron! Butter wouldn't melt in his mouth. One only has to read Darkness Visible, his account of his nervous breakdown, to see that he couldn't tell a neurosis from a tea-pot, and neither from reality. As one of our reviewers wrote not long ago about the book Unholy Ghost,

As soon as Styron starts in on his version of The Miseries, we get the feeling that there's something screwy. He is capable, without even trying hard, to come up with some startling howlers, making him a modern-day neo-psychological Polonius. "I shall never learn what 'caused' my depression," he tells us, "as no one will ever learn about their own." No one? This ignores what many perceptive writers (such as Larry McMurtry) have found out. Most have a damn good idea of the source of the blues and have consequently acquired a fair amount of personal insight from it.

Go to the full

readingThe Poets Laureate Anthology

Elizabeth Hun Schmidt, Editor

(Norton)This "Poet Laureate" business is a bit of a humbug. That the U. S. government would subsidize someone as flaky as a poet, subsidize the writing (and publishing) of poetry. In fact, it's downright silly to suppose such. For poets should be eternally, as they say in the Bible, "kicking against the pricks."That someone as disreputable as a Real Poet (vide Charles Bukowski) should have an office in the august Jefferson Building in Washington, D. C., along with $35,000 a year is not unlike, as Mark Morford has it, putting feta cheese in the freezer: it gets crumbly, stinky, goes bad.

This anthology is, then, more or less a rectal thermometer. It tells you about the fevers and pains lurking in the systems of the run-of-the-mill poetasters of America ... the condition of the state of national aesthetics by those who run the show. One of the better poets, William Carlos Williams, was duly appointed to serve as Poet Laureate in 1952, and was subsequently pilloried for his rather mild political views. He was dying of heart disease; the godzillas in United States Senate stabbed him so cruelly that he was not able to serve, up and died. As Williams wrote, appropriately, "For verse to be alive, it must have infused in it ... some tincture of disestablishment, something in the nature of an impalpable revolution, an ethereal reversal."

§ § § One of the pleasures in this volume is running into the usual poetic wusses (Maxine Kumin, Penn Warren, Reed Whittemore), but, also, discovering some brand new ones: Robert Fitzgerald, Gwendolyn Brooks, William Jay Smith and --- saints preserve us! --- Mona Van Duyn. In her 1992 poem, while she was serving as our national poetic treasure, she wrote and published a poem comparing William Clinton, "President Elect," to Michelangelo's David, "Raised on a marble platform, he pure white, / naked, marble beauty glows in bright light..."He towers and shines before us, perfect in body

fair of face --- perfect in spirit too...

Time cannot smudge his form nor erase his story.

Go to the full

reviewPoets Translate Poets

A Hudson Review Anthology

Paula Deitz, Editor

(Syracuse University Press)This fat book is parceled out amongst translations from twenty-five different languages, including Russian, French (and Old French), Greek (and Ancient Greek). There's Swedish but no Norwegian, Vietnamese but no Laotian, German but no Old High German, Macedonian (but no Albanian, Roma, Bosnian nor Aromanian) ... and Polish, Portuguese and Provençal; but, alas, no Punk (nor Neo-Punk).Japan? Certainly it deserves more than two obscure poets --- Motomaro Senge (1888 - 1948) and Kakinomoto No Hitomaro (660 - 708) with a mere six pages, including a few awkward translations: "This is the news the runner brings, / news like the twang of the yew-wood bow..."

Or,

And I am lost, like a man undone, going on a journey

but going in grass, without words, and the way lost,

and a grief in my guts

like the salt-burning of the fisher-girls of Tsumu.Where, we ask, where is Matsuo Basho's frog or fallen snow ... or his dear horse or bugs?

Fleas, lice,

a horse peeing

near my pillow.And China? Are we to be satisfied with two poems by Tu Fu, (712 - 770) while we have available in translation one done by Ezra Pound in 1936 --- from Riyuku --- one that makes such loving sense, one that should be reprinted everywhere, again, and again, and again:

At fourteen I married my Lord you.

I never laughed, being bashful.

Lowering my head, I looked at the wall.

Called to, a thousand times, I never looked back.At fifteen I stopped scowling,

I desired my dust to be mingled with yours

For ever and for ever and for ever.

Why should I climb the look out?Go to the full

reviewPoet Power

The Complete Guide to

Getting Your Poetry Published

Thomas A. Williams

(Sentient)"Complete?" Well, not exactly. Perhaps A Partial Guide to Getting Your Poetry Published, Perhaps would have been a more honest title.Most of the facts are here: how to submit poems, where to submit them, how to publish your own, where to go for further information. But several major details are missing. For instance, Williams suggests that you might want to "set up a business" to publish your poetry.Don't forget that as a self-publisher, you are a businessperson. There will be significant financial benefits to you. Tax savings can be substantial.

Tell that to the IRS. In any five-year period, they will permit you to lose money for two years. The three others must show a profit. If not, you are probably in for a dreaded tax audit, which is scarcely worth, we would wager, your slim volume of verse.There is something even more troubling about Williams' publishing advice. He is trying to make you forget that there are about 10,000,000 people in the world who consider themselves poets who are forever and a day sending their stuff out to magazines and newspapers. He doesn't tell us that those who mail off stuff coldcock to The New Yorker, Harpers, The Virginia Quarterly Review, The Sewanee Review are wasting their time. These magazines ship this stuff back by the cargo-container load. Some magazines like the Atlantic don't even bother to open submissions --- they stamp "refused" on the envelope.Williams shows a table called

SUBMISSIONS LOG Where Submitted Date Result Little Review 1/5/99 "Not right" West Coast Poets 2/15/99 "No, but wants to see more" New Yorker 3/4/99 Accepted "Staten Island Blues" This last item, if it popped up in accounting, would be called "cooking the books," or perhaps, "Enronitus."

Ultimately Williams advises you to publish it yourself. He doesn't like the word "Vanity Press," though. He prefers "cooperative publishing." Well, OK --- but it's still vanity. He does not mention that if you print up 1000 copies of your love-child poems, you could probably spend the rest of your life wondering how to get rid of the 980 turkeys you'll still have under your bed or in the garage after giving 20 to your best friends, family, and fellow-workers.

Go to the full

review

Swarm

Jorie Graham

(Ecco/Harper Collins)The American poet Jorie Graham, the critics tell us, can be compared to T. S. Eliot, Emily Dickinson, and e. e. cummings. A reviewer in the Post-Dispatch said that Graham's style "is so personal that the poems seem to have no author at all..." The "Library Journal" stated that her style is "unapologetically solipsistic," one that is "almost quaintly Miltonic." And the august Richard Eder in the august New York Times said hers was a "remarkable voice." He compared her to Rilke, and said "Even as the brain struggles, the neck hairs lift."Now I have to admit that when I read stuff like this, and then leaf through her poems, my neck hairs don't do much of anything, but the rest of me gets a little weird. I feel like I've just landed on earth from the planet Ixneabar, discovering a world filled with conspiracies of nonsense.

Agreed, on every page of this, her newest booklet, we find end-stopped lines. This makes it poetry, n'est-çe-pas? We also find a heap of five-dollar words, like "empyreal," "stasis," "spezzato," and "enjambment." And the volume is jam-packed with all your hoary classical references --- Agamemnon, Eurydice, Socrates, Lear and Ulysses.

Furthermore, there are words and phrases that some of us innocents can't make head nor tail of: "the swag of clay," "nerves wearing only moonlight/whelm sprawl," "The furrow of the hard now." There are lines like

looking through the end of afternoon into your glance andlet no one see us here whitening in the century andthe slow river of my spine. Who can tell if it's poetry or merely oatmeal mush? I sure can't.Go to the full

reviewMonologue

Of a Dog

Wisława Szymborska

Clare Cavanagh

Stanislaw Barańczak

Translators

(Harcourt) The Nobel Committee sometimes gets it right, such as with the 1996 literary prize to Wisława Szymborska. She's Polish, and her poems are wistful, funny, occasionally shaking, always comprehensible. She can (and often does) write about dogs and gods and stars and tablecloths (being pulled down by very young little girls). She writes about dying and graveyards, graveyards with "tiny graves" --- but the verses are never sententious, never teary:

The Nobel Committee sometimes gets it right, such as with the 1996 literary prize to Wisława Szymborska. She's Polish, and her poems are wistful, funny, occasionally shaking, always comprehensible. She can (and often does) write about dogs and gods and stars and tablecloths (being pulled down by very young little girls). She writes about dying and graveyards, graveyards with "tiny graves" --- but the verses are never sententious, never teary:Here lie little Zosia, Jacek, Dominik,

prematurely stripped of the sun, the moon,

the clouds, the turning seasons.Hers' is not so much a questioning as a round gentle O of wonder:

Let people exist if they want,

and then die, one after another:

clouds simply don't care

what they're up toShe reminds us of e. e. cummings: funny, sly, shy to condemn, wondering, wondering, always wondering ... why, for instance "we have a soul at times" but "no one's got it non-stop,/for keeps."

She also brings to mind Lawrence Ferlinghetti before he got swept up by Too Much Fame. She got Fame, too, but evidently, unlike him, it did not upset her balance, nor her wistfulness, especially when we find her writing lines like,

let's act like very special guests of honor

at the district fireman's ball,

dance to the beat of the local oompah band,

and pretend that it's the ball

to end all balls.I can't speak for others ---

for me this is

misery and happiness enough:just this sleepy backwater

where even the stars have time to burn

while winking at us

unintentionally.It is those jumps that make us want to ring her up right this minute and invite her to the annual Carpathian Firemen's Ball; or perhaps, if she is adverse to a night dancing the polka, to spend a few hours lying about her yard gazing at Orion winking. Unintentionally.

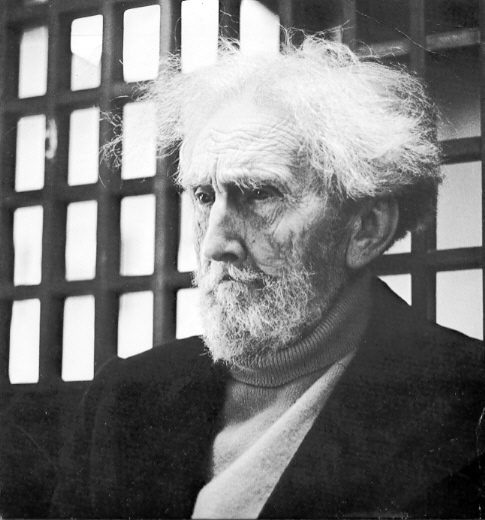

The title poem might have some readers on edge especially the present generation, so idiotically called "boomers" when as far as we can see they are booming only when stoned or drunk. These nitwits are perfervid in their ignorance of anything in history that happened before the advent of the Lemonheads, Rancid, or the Arctic Monkeys. Szymborska's poem tells of a dog, a very special dog, owned by a special, awful 20th Century figure. When judging art, we are faced with the question of whether a poem works if you and I do (or do not) know the referent. Who is she writing about here? Probably no one under forty will be able to say. Out of simple affection for the writer, let's ruff the question of whether or not it is a piece of high art.

Meanwhile, know that the volume Monologues of a Dog is an impeccable face à face edition: Polish to the left, English to the right. Szymborska's one albatross bears the name of "Billy Collins." They say he's a poet; he should stick to poetry ... his 1500 word Forward to the edition could have been reduced to a dozen or so lines, preferably of verse. Szymborska herself doesn't care to cloud the horizon with more than a page or so of writings; why should he?

Collins comes up with the dumb idea that American poetry is taken up solely with time, where other poems of other nations are of history. Tell that to Emily and Walt and Ezra, Billy.

And he, too, is so bewitched by the phrase carpe diem that he uses it twice in two pages. Dumb me. I had to look it up. It means "seize --- or 'pluck' --- the day."

Forget the poetasters and dogsbodies; pluck the strings lightly, and daily, for Wisława Szymborska ... the dreamsmith of versifiers.

Go to the full

review