Time and Again

The Classic Illustrated Novel

Jack Finney

(Touchstone)

The American government has embarked on an experiment in time travel. From the beginning, scientists involved have decided that it is not to be a physical process, but a psychological one. Thus, those who are to go back in time are to prepare by setting themselves mentally in the era they are to visit.It's a matter of immersion. Si Morley is selected to visit 1880s New York so he moves into the Dakota apartment --- John Lennon's old placee near Central Park --- and they set him up with rooms that are filled with artifacts from of the past.

He starts dressing in clothing of that era; those who visit him or bring him food, ice, and other goodies are to be appropriately dressed, speak the language of the past. His rooms are lit by gas and heated by a wood fire; there are no radio or television sets; newspapers of 1882 are delivered to his door every day.

Meanwhile, he puts himself in a trance so he can begin to know he's back there. A visiting psychologist aids the process by putting Si in a place "as restful as you've ever known."

When you wake, everything you know of the twentieth century will be gone from your mind ... Everything you know of the past eight decades is washing out of your mind: everything. All of it. Large and small. From the important to the smallest of trivia.

"January 21, 1882 ... that is the date; that is the time we're in."

And it works. One night Si wakes, leaves his room, goes out into a snow-filled Central Park in January ... but it's 1882. There comes a "light, airy, one-seated sleigh drawn by a single slim horse trotting easily and silently through the snow." And with this, Morley is back to the New York City of horse-drawn buses, women in long dresses (with bustles!), men in top hats and coats to their ankles and only the jingling of bells and the laughter of children and the great silence of a huge snowy city.

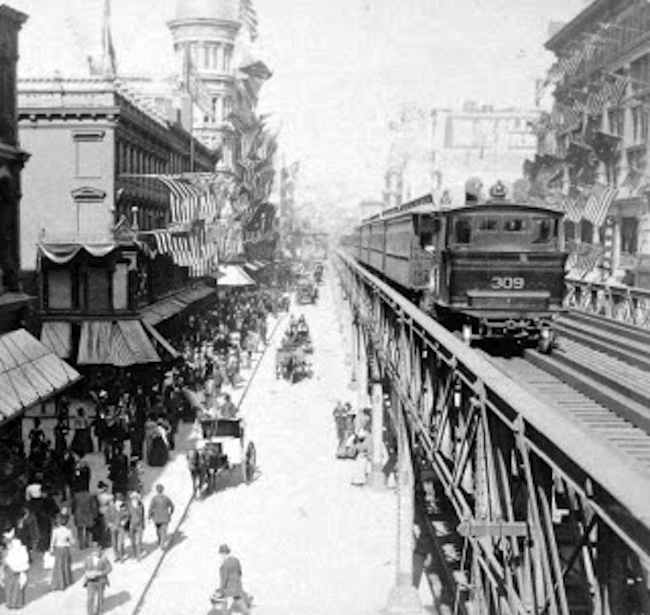

Time and Again was immensely popular when it first came out a half-a-century ago. It became an underground classic. Finney did his homework, and although it takes too long for the machinery to crank up (we don't get to see our first sleigh until page 130) ... once we get there, we, like Si Morley, are reluctant to return to a city filled with hundred-story skyscrapers, a smog-filled sky, sirens and blaring taxis everywhere.The author brings the late 19th century to life, the good and the bad of it: the rich, ornate mansions alone Fifth Avenue, the colorful wagons with country scenes painted on their sides, the farmland still there in upper Manhattan, the muted dresses of the women, the men with fedoras and canes, the trees everywhere, the tallest structures being only church steeples.

Si climbs into a "little wooden bus," and when the next passenger gets on a few blocks further on, drops his nickel in the tin box, and we get to study this man in his "odd high-crowned black derby hat, a worn black short-length overcoat, his green-and-white-striped shirt collarless and fastened at the neck with a brass stud."

It is the details that capture the reader, and Finney makes sure we are back there ... and that we want to be back there: the darkness everywhere (no electric lights yet), the noise of iron wheels on cobblestones, the ferment of it all. When we visit the postoffice, we find it "such a ridiculous building, all windows and ornamental stone columns riding five stories to a roof of shingled towers; cast-iron railings; an ornamental cupola, and fluttering from a flagpole, a long painted pennant on which was lettered POST OFFICE."

But it isn't all lovely 19th Century panorama and the moon hanging over the city and beautifully-dressed women. We get a full picture of the life (and the death) of the times. A woman on the bus turns, and "I saw her face clearly and glanced quickly away so that I wouldn't offend her, because her face was scarred with dozens of pitted cavities, and I remembered that smallpox was almost commonplace still."

When the bus gets to the corner of Forty-second Street, he looks for the New York Public Library and sees only "the base of an enormous pyramid, tall blank walls slanting inward, running clear down to Forty-first Street on Fifth." It's the old Croton Reservoir. And when he goes into the post office, there is a feeling of "astonishment and disgust:"

Just about every last man, without breaking stride, aimed a shot of thick brown tobacco juice as one of the several dozen cuspidors scattered around the big floor. Some were expert, hitting the mark squarely and audibly, then walking on toward or past us looking pleased and self-satisfied. Others missed by a foot or more, and now, our eyes used to the gloom of the feeble lighting, we saw that the floor was soiled everywhere you looked.

The plot of Time and Again is nicely wound. Morley is on a mission from the federal government --- ninety years hence --- to make sure that by moving a few people around, President Cleveland will agree to the U. S. taking over Cuba (thus Fidel Castro will never come to power).

But there is a paradox: Si is under exact orders to be a minimalist. He is to involve himself as little as possible in the lives of people around him. Because no one knows how one little touch of his can change events between then and now. By plucking a leaf here, brushing against a person there, dropping a match on the street --- and certainly by upending an American foreign policy --- he can ripple the river of time so that, by 1970, someone may go missing, a chain of events may alter our present world entirely.

There are signs early on that should Si continue his journeys to 1882, our present will be altered. The organizers of the project decide to jettison it. They inform him of that fact. But it's too late. He's already smitten.

Morley and the author (and the reader) are all hooked, and so we get to visit old New York again and again. We become time-travel addicts.

Which may explain why this novel, despite its (sometimes) wheezy machinery gettings us back and forth over such time-leaps develops quite a hold on us ... and why it had such a hold on people when it came out.

For people of Finney's era were beginning to understand the price of Modern America. Those of us who grew up out of the depression and WWII were just becoming aware of the destructive element called Progress. Our cities were being trashed by a bomb cobbled together by the banks, the real estate industry, and those who owned the government --- movers and shakers utilizing the rubric of eminent domain and "urban planning" and "redevelopment" to destroy our heritage, to make themselves unalterably rich.

--- Richard Saturday