San Francisco Lithographer

African American Artist Grafton Taylor Brown

Robert J. Chandler

(University of Oklahoma Press)

Racism is such a very odd business. The idea that one can or should be excluded on the basis of one's culture or religion or simple pigmentation is neither wise nor rational. If I want to dislike someone, I would hope it would be because that person is a creep, and cruel, and won't keep his hands off me, or eats with his mouth open, or steals my toys. That makes sense. To scorn someone for the stuff they do when they are praying or what they look like in the light of day seems to be wretched excess.It was not always such. In his book Racisms, Francisco Bethencourt tells us that it all began in the 15th Century, in Iberia. When Isabella and Ferdinand weren't busy sending off corsairs to rob and enslave the simple heathen, they were promulgating a series of laws to exclude the "Moriscos" (peoples of North Africa), the converted Jews, and the "Roma" (gypsies). All these were sent into exile, forbidden ownership of land or rights to do business. As David Armitage reports in the TLS of July 25, 2014, the royals created a discrimination based on "on grounds of ethnicity rather than belief."

He concludes: "Bethencourt's achievement is to show that racism, in all its forms, was contextual and ultimately reformable, not innate and hence inevitable." Racism comes to seem, at least in this study, a matter of laziness, if not convenience. With nothing else available to block others from participating in the market economy, those who promulgated the "purity-of-blood statutes" were operating within "novel hierarchies of continents, peoples, and civilizations," using the simplest means possible to classify others: religion, custom, color of skin, accent or language.

Racisms suggests that all forms of this particular social blight are "relational, hierarchical, prejudicial, and found in policies, not just attitudes."

This Western weed hybridized wherever it landed. It took root most firmly in the Americas, where creole societies overwhelmed native peoples, and where slavery and the plantation system left their most toxic legacies.

"The western hemisphere remains the region most scarred and stratified by the residues of racism.

§ § § Grafton Taylor Brown was born in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania in 1841. His family was black, recently escaped from South Carolina. As Chandler emphasizes, it was dangerous times for blacks to be without a home to hide in --- even in a supposedly "free" state like Pennsylvania. By Grafton's ninth birthday, "bounty-hunting slave catchers kidnapped free African Americans in the North." Whether they were slaves or not, they could be smuggled to the South and sold into bondage. The bounty for the kidnappers was $1,000 per slave.

Seven years later, Roger Brooke Taney, the fifth Chief Justice of the Supreme Court (he wrote the majority opinion in the Dred Scott decision), stated that

blacks were beings of an inferior order; and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations; and so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.

By 1860, Grafton Brown was living in California, and "passing" by dint of his fair complexion. In an enlightening "Afterword" to San Francisco Lithographer, Shirley Moore discusses the subtleties of passing in mid-19th Century America: Throughout the country, "one drop of black blood" established one, per se, as black.

The one-drop rule not only became the legal and social determinant of racial identity but also governed social and economic mobility and stood as a marker of moral character.

One could "pass" by what she calls "racial presumption:" what people saw was what they got. After arriving in California, and with his fair complexion, Grafton Brown embarked on his full-time part in contemporary theatre: "Passing was a performance in which the actors assumed their roles temporarily or for a lifetime."

Winthrop Jordan has noted that the transformation to whiteness rested on a "conspiracy of silence" not just for the individuals making the transition but for the "biracial society which had drawn a rigid color line based on visibility."

What other blacks might see as "a form of opportunism and acquiesence to the racial status quo" was in the western part of the United States "particularly conducive to people of African ancestry becoming white by presumption."

§ § § One cannot overstate the economic advantages of appearing white. In the 1860 census, of the 5,000 blacks living in San Francisco, practically none of them worked as professionals. Instead they were blacksmiths, boot makers, bricklayers, cigar makers, house carpenters, milliners, painters, plasterers, seamstresses, ship carpenters and tinners. The only black professionals listed were soap manufacturers and tobacconists. No lithographers appear because by that time for Grafton Brown had completely and safely passed.

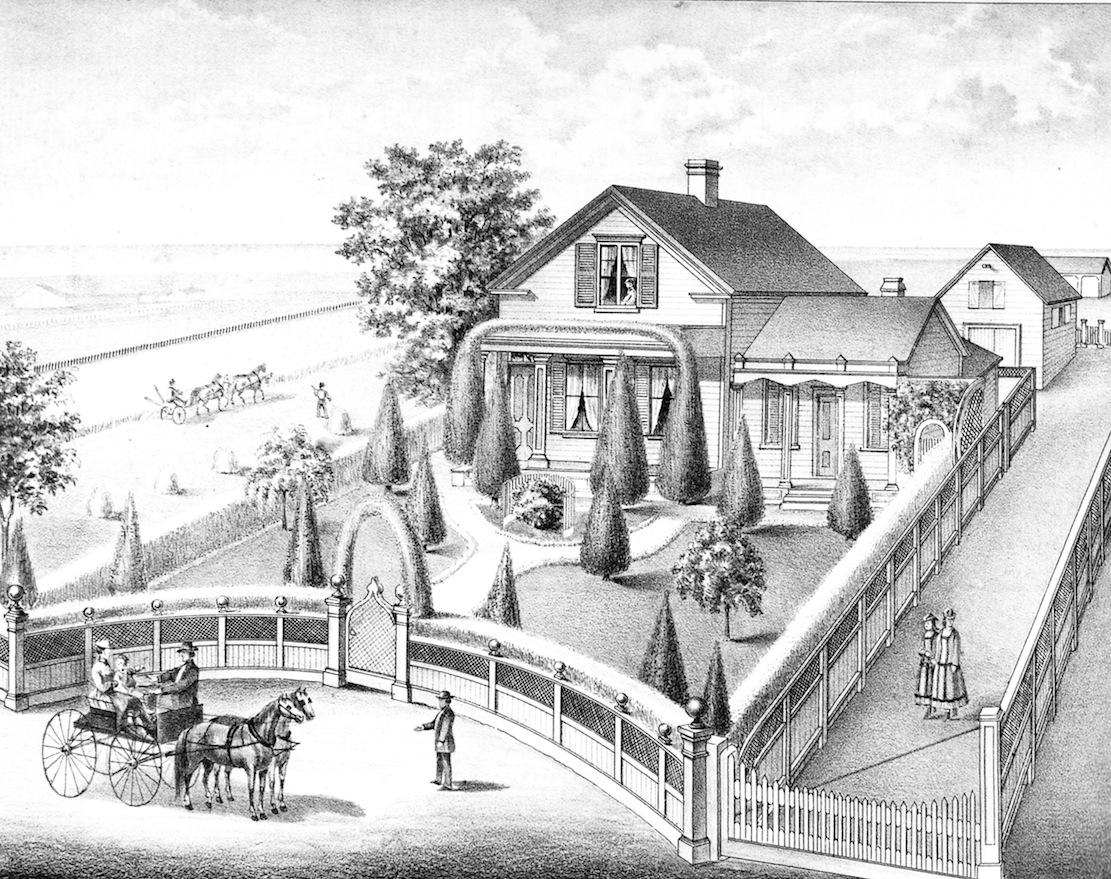

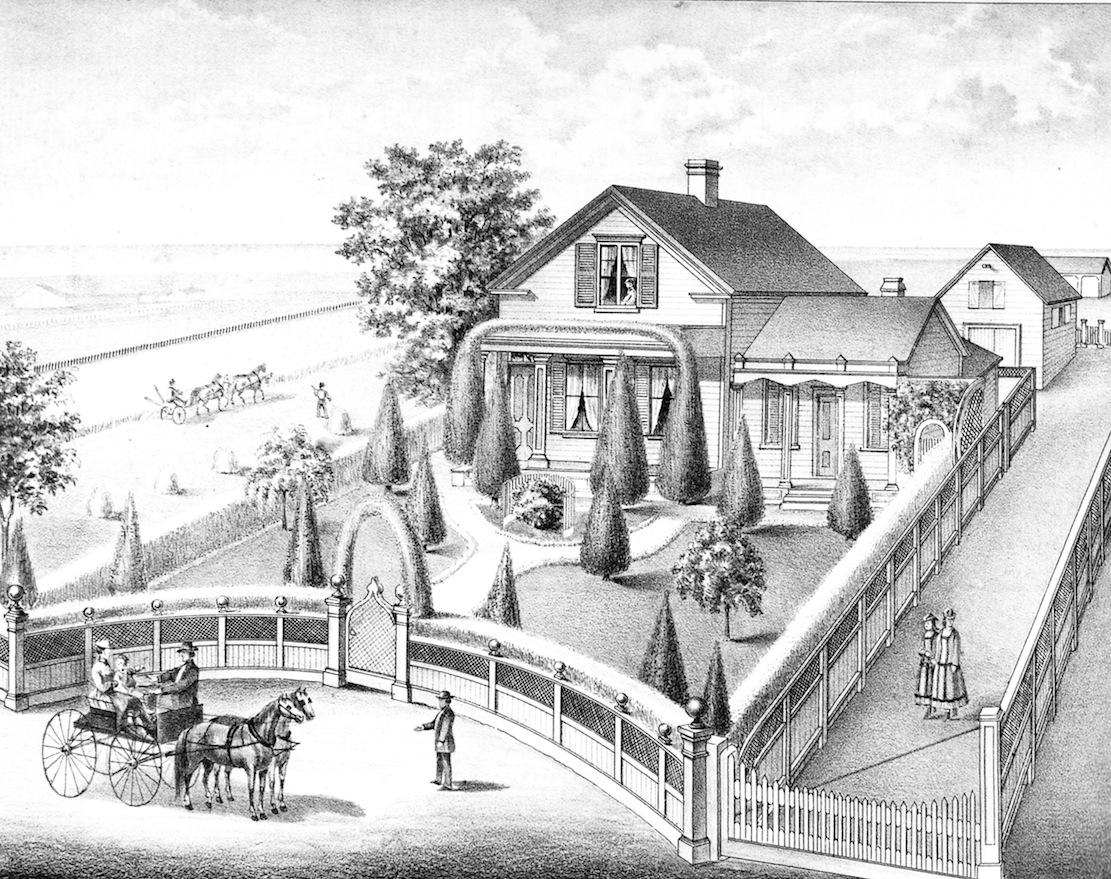

From running an impressive printing and lithographing plant, he found himself taking in business from some of the more successful local companies: producing a bond for the California Cotton Growers, a membership certificate for the Cambrian Mutual Aid Society, a privately run Letter Express for Wells Fargo, a plate for a book designed by the First Congregational Church, billheads for wine and liquor merchants, and elaborate maps for new developers throughout the Bay area.

By 1882, Brown had shifted gears, moving to the Pacific Northwest to become a successful landscape oil painter, had leaped, as Chandler tells it, "from disdained lithography to the airy realm of fine art." His paintings resembled, according to the writer, "the softness of the romantic Hudson River school, the most popular in the later part of the 19th Century, expressing awe in the face of the glories of nature."

§ § § Although lavishly illustrated, San Francisco Lithographer lacks one thing. Grafton Taylor Brown. There are copious details about his successful business in San Francisco, his later work as a professional painter in the Pacific Northwest, and his last days in St. Paul, Minnesota working as a civil engineer --- but all these are gleaned from city directories and records, census reports, and lithographs and print collections and paintings from here and there.

Yet, as far as I could determine, outside of his wonderful illustrations, there's nothing from the hand of Brown himself, although there is a twenty-five-word will in his own hand, signed by him in 1899, leaving everything to his wife Albertine. That's it. Thus we lack any word from the man himself... telling of his life and times, his successes and failures, his own narrative of having to pass.

He obviously learned to keep his origins a secret, to deny family and even friends and all personal connections. He was forced to survive as an orphan of his race in the America of the times with its naked scar of racism. Thus, it was necessary for him to leave nothing behind except his art and craft, keeping his life-time theatrical role a secret, "performing whiteness so effectively as to become white." We can only guess the bitterness of it from one who was able to sketch it, W. E. B. Du Bois:

One ever feels his two-ness --- an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled stirrings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.

--- Sara Washington