A Unicyclist's Guide to America

Mark Schimmoeller

(Chelsea Green)

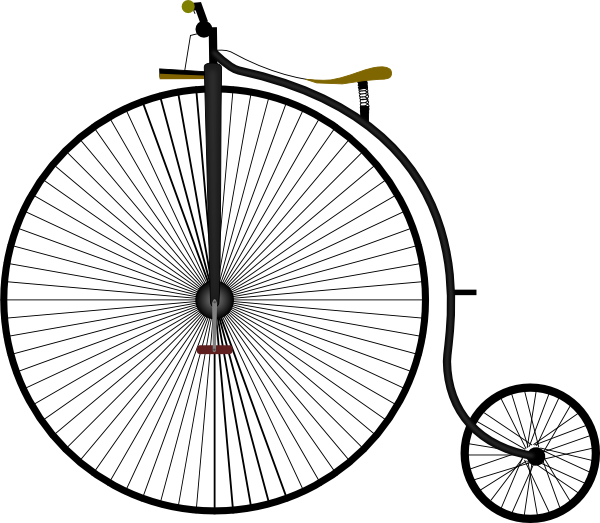

You remember those funny old bicycles from 1890 with the huge wheel up front, the tiny one behind. You wondered how anyone ever got up on one, much less rode along without falling over, what they called in those days a "heading."

You remember those funny old bicycles from 1890 with the huge wheel up front, the tiny one behind. You wondered how anyone ever got up on one, much less rode along without falling over, what they called in those days a "heading."Evidently it's less difficult than it looks, but more important for our story is that those "penny-farthings" (that's what they were called in England: large penny up front, tiny farthing behind) were essentially unicycles because for anyone with a sense of balance --- and you did need that --- one could stay aloft without a seat, just using your legs, standing on as it were two ever-moving pedals, going forwards or backwards, trying not to fall in a tumble.

It wasn't as difficult as it sounds on a unicycle, unless you, like Schimmoeller, chose to ride it across mainland United States. Which he did, in 1992, in a period of months, and which is, ostensibly, the subject of this book: pedalling single-mindedly (single-wheeledly too) from Upton, North Carolina to Lukachukai, New Mexico --- taking a short break to go back to be with his family, in Kentucky, in the summer of that year.

§ § § The author says that riding a unicycle is moving like a pendulum. Press on the left pedal, you move left, right right. You are up there on your seat, nothing in front of you or behind you. Your hands are free. At times he takes notes while he is going down to a level road, but it hinders the balance because you have to (as it were) pedal the air with your arms to keep balance. Still, he could have written the whole book while he was passing through, say, Oklahoma.

We find ourselves rather awed by the whole presumption here: so many miles seated on this one tricky wheel, with rain, snow, wind, passing cars, trucks, tractors, pedestrians and, further west, cows and buffalo. How did he do it? Didn't it hurt, uh, down there? Chafe him? Rub him the wrong way? Schimmoeller is a stolid sort, doesn't --- or won't --- say.

Besides, he wasn't up there in the driver's seat all the time. There are certain roads, certain winds, certain physical presences (speeding cars and trucks; no friendly paved shoulders) that make it lots less life-threatening to walk your unicycle. It in front, you behind.

He learns and we learn (this is our first trip together) necessary precautions. Stay out of cities if possible. Never try to use a busy highway to get in or out of town. Look for the roads on the map that are the little dinky lines between the big ones. Avoid the four-lane or six-lane highways. Try times when there will be no traffic, or if any traffic, wide shoulders are preferable. Calm day. No wind best. No tornadoes, please. Nor drunks. Best to avoid people standing along side the road who might be laughing at him.

For he is a reticent type. Tells us at one point that he was "someone who wished not to be seen." He's talking about finding a meadow or a field or a pasture where he can sleep for the night, but we also get the feeling this guy is not one to be looking for companionship. He doesn't waste words, either, at least not on the page; we doubt he would in person.

Still, there you are with him half-way through Ohio on a bloody unicycle, and we are thinking "this guy tells us he is the retiring type. Howcum he isn't walking, running, riding a Schwinn, flying cross-country on a hang-glider?"

§ § § One of his favorite cities --- ours too --- is Scottsville, Kentucky. That's where the Mennonites live and work and play, where they let him stay a few days, helping to pitch manure, mow the lawn, take a buggy into town: get off a unicycle and, to go for ice cream, climbing into a horse-drawn buggy to do so; does this Schimmoeller have transportation issues?

What we'll always remember from Slowspoke is the people in places who were nice to him. We've come a long way with him, have come to enjoy his company, don't care for it when people laugh at his long hair, stare at him, jeer, drive too close to him, throw beer bottles at him, or worst of all, try to convert him to Jesus.

We want them to let him alone because he is so easygoing (except on himself) and, for sure, is nuts about trees and birds and creatures of the woods. Especially trees. If you ever go visit him and his wife there near Frankfurt, Kentucky, these are the trees you'll meet (he'll introduce you): redbud, plum, white oak, maple, ash, shagbark hickory, sugar maple, cedar --- amidst thickets of blackberry, black haw, ironwood, black raspberry, mulberries. From his comments, we think --- no, we know, that he is a treehead.

You'll soon figure that one reason he decided to go so far on so little is that he is a minimalist, not unlike those Mennonites. A unicycle is a minimalist dream: one seat, one tire, a fork, two pedals, several dozen spokes. If you are going across America, I guess it's the simplest way, outside of a pogo stick. Maybe next time around we can talk him into that.

In Filley, Missouri,

I asked directions at an antique store. "I can see what your problem is right away. You just have one wheel," the owner, Len Dennis, told me. He stood outside his shop.

I've managed to come all the way from North Carolina," I said.

"You're from North Carolina?"

"Actually, I'm from Kentucky."

"I'll bet you're lost."

I told him I needed to get to Road CC on gravel roads.

"In other words, you're lost. We haven't had a unicycle traveler yet who has stopped here and hasn't been lost."

That's one of the funny ones (there are quite a few jokers to be found on these pages).

Then there are the ones that manage to irritate Mark. And the rest of us, too. Like the guy from the radio station in Clarksville, Kentucky who flags him down for an interview.

Now I just want to know one thing, and anybody who has seen you, I imagine, has the same question. How do you, carrying that big pack and balancing on just one wheel, keep from falling?

He annoyed me. In another context I would have appreciated the question, for I'd thought a lot about falling. I would have explained how a unicyclist didn't attempt to completely avoid falling, a process set in motion immediately after mounting. Rather, the goal was to keep from falling too far. ... The act of act of falling partway plus corrections equals movement.

§ § § Who is this Schimmoeller? He graduated from college and got an editing job at The Nation and then he drifted back to his family's place in Kentucky and sooner or later met Jennifer and they built a place in the woods off the grid: water from well, solar stove, cabin built from a near-by timberland. One of the most charming passages is Mark leading a would-be assessor (they're trying to get help from the Nature Preserves Commission) up to and through his house:

The ground directly ahead slopes almost immediately downhill past plum and redbud and gets swallowed again by woods. To the right, a mowed path leading to the garden goes past highbush blueberries in raised beds and next year's firewood, cut, split, stacked, and covered with tin. To the left, on the east, is our cedar board-and-batten house. Steppingstones lead him to the back door, which is made out of cedar as well --- in the same board-and-batten as the house --- with a clear window. The lever handle is inset in a bit, due to the fact that this door we built last winter turned out to be thicker than standard.

Once inside, everything described minutely, and the smell of cedar everywhere cinches it. Someday, I swear I'm going to go to Kentucky and see this house on my own. If I can ever find it --- even though Slowspoke convinces me that Mark Schimmoellar is so retiring that when I approach the house he'll probably be hiding in the root-cellar. I'd probably have to put out an APB with the Kentucky State police just to find him.

There are books like this that are so nice that, like Holden Caufield, you want to call up the author and tell him (or her) what a great job he (or she) has done. The same way I felt reading Craig Childs, José Sarney, Brendan O'Carroll, César Aria. Or the travel-book writers like Stanley Stewart in China, Santo Cilauro in Molvanîa or Hugo Williams around the world.

This is not only the tale of a man on a unicycle, one who has turned his back on freeways and power plants and supermarkets and television. More, it's a man who has honed a fine edge to what he has learned: what works, what doesn't work, what you need, what you don't need in life; details that end up making Slowspoke a classic.

We have here a man who can write so endearingly about carrots down in his root-cellar that you want some right now: "In this dish of January carrots there's a portion of that sweetness that the first fall frost gives the carrots; yet the sweetness is complex enough to suggest the possibility of bitterness, and an image of the feathery green tops comes to mind, how touching them can coat your hand with their sharp smell. Oregano tweaks the carrots' complex sweetness to release in the mouth the feel of a humid summer day."

But in my mind the taste also includes the transition from summer to winter, the change in temperature --- not the quick change from day to night, or from month to month, but the change that happens in the earth, in the cellar where they are stored, where it appears that nothing is happening. Yet in the winter the cellar feels like fall; in the summer, like spring.

It's a little like going from North Carolina to New Mexico. On a unicycle.

Why?

Because it's just something that you just have to do, all the while knowing that it cannot be pushed, rushed or --- even --- avoided.

--- L. W. Milam